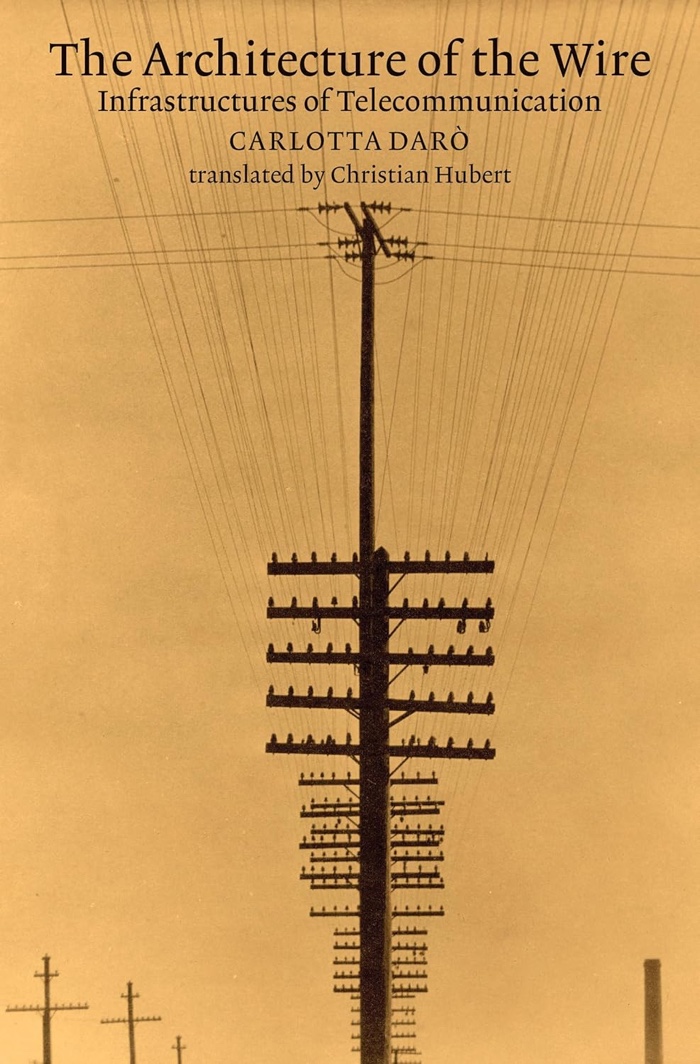

The Architecture of the Wire: Infrastructures of Telecommunication, by art and architectural historian Carlotta Darò. She is Associate Professor at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture Paris-Malaquais and currently a guest senior researcher at ETH Zurich. Translation by Christian Hubert.

The Architecture of the Wire is grounded in the thick materiality of telecommunication systems. In the cables, wires, poles, transmission towers, antennas, switches, conduits, phone booths and other objects that found their way into homes and landscapes. Carlotta Darò posits that electrical technologies for sound transmission didn’t develop autonomously from architectural and urban design. They were interwoven into modern planning, physically integrated into urban, rural and domestic architecture.

Not only did their physical presence and organisation influence the constitution and organisation of modern cities, but energy and telecommunications infrastructures also had an impact on the structure of societies.

The book tells the history of telecommunications networks. At its core are not famous inventors and engineers, but a series of urban and rural transformations, seeped in enthusiasm for scientific progress but also in accidents, anxieties, utopian scenarios and resistance to new objects, grids, systems and the new complexification of society.

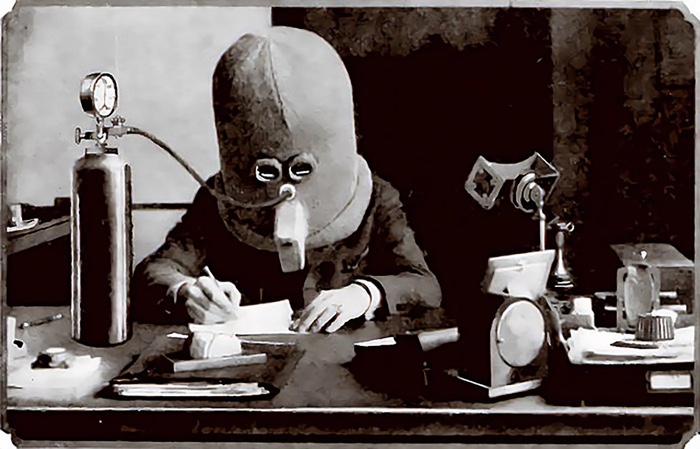

Hugo Gernsback with his isolator (external noise eliminator). Published in Science and Invention 13, no. 3 (July 1925)

On 5 November 1898, Eugène Ducretet succeeded in establishing a radio link in Morse code from the top of the Eiffel Tower to the Pantheon four kilometers away

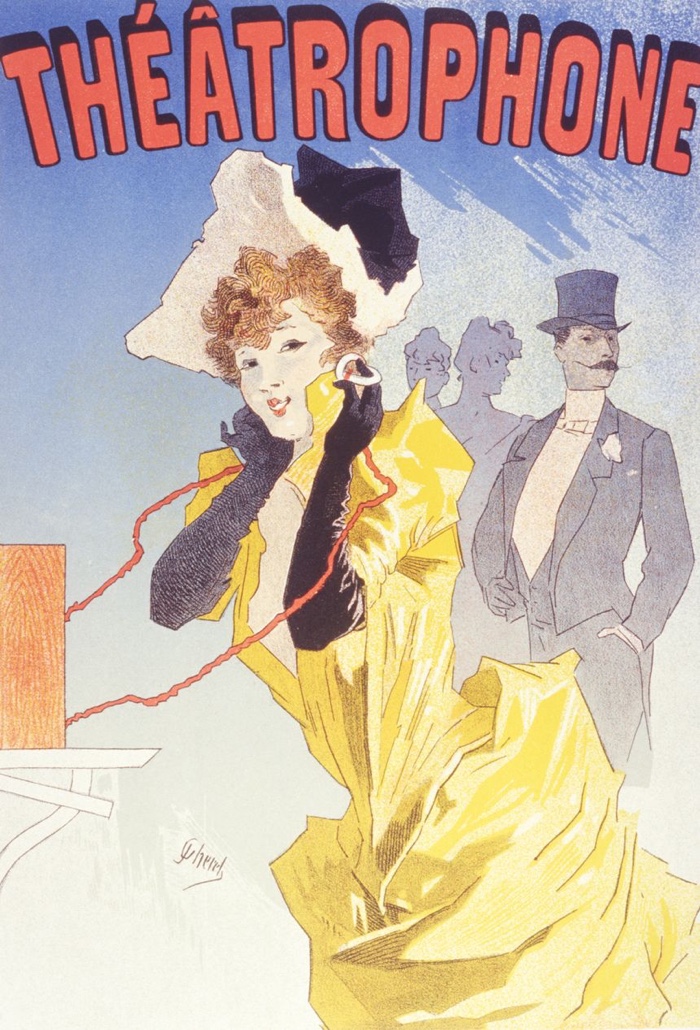

The Architecture of the Wire: Infrastructures of Telecommunication balances the gritty realities of ugly utility poles and systems breaking under the weight of snow with the fantasies of an invisible, hidden, immaterial infrastructure. It goes from nerdy details about the distribution of wires in conduits to Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision of a techno-enabled decentralised city that would bring society together; from the théâtrophone (the first applications of the telephone in 1876) to how the radio saved the Eiffel Tower from its planned demolition; from the USA vision of “linear imperialism” to László Moholy-Nagy’s Telephone Pictures.

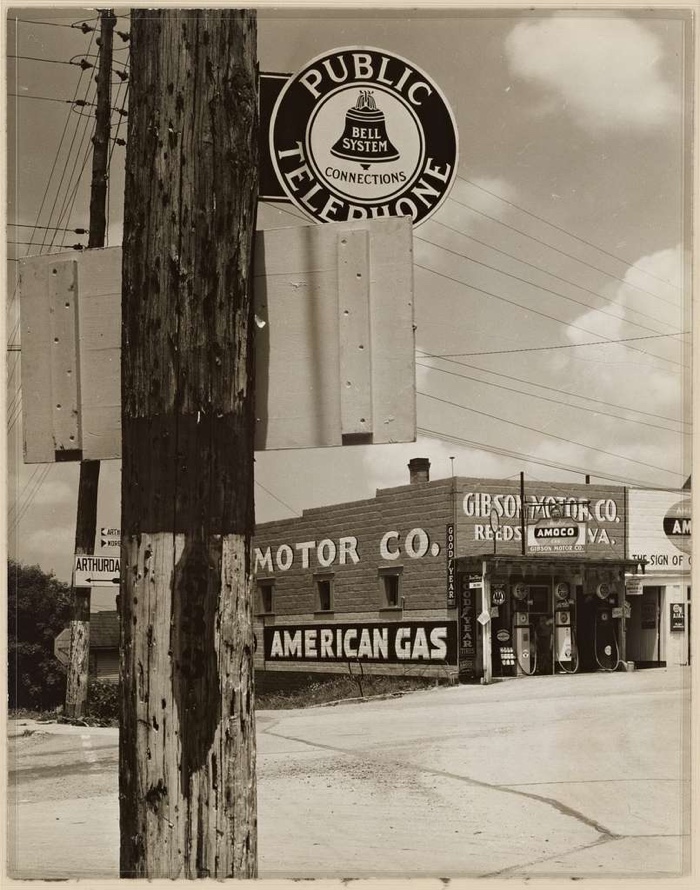

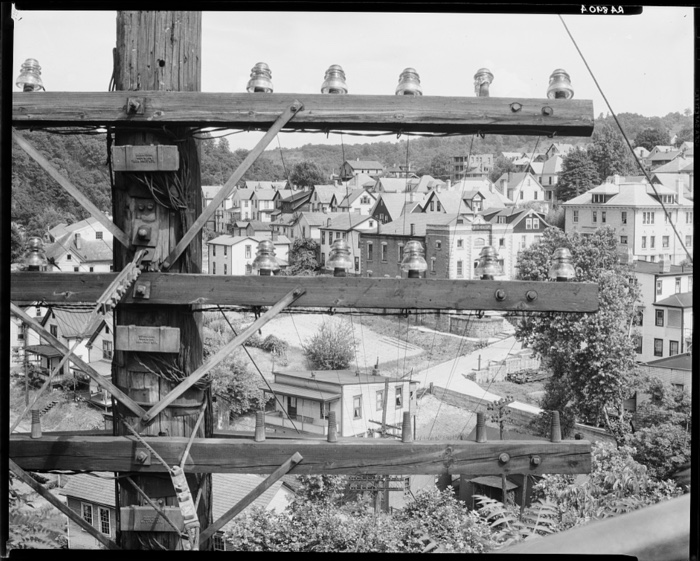

Photograph by Walker Evans, Reedsville, West Virginia, 1936. Library of Congress LC-DIG- fsa-8c52037. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

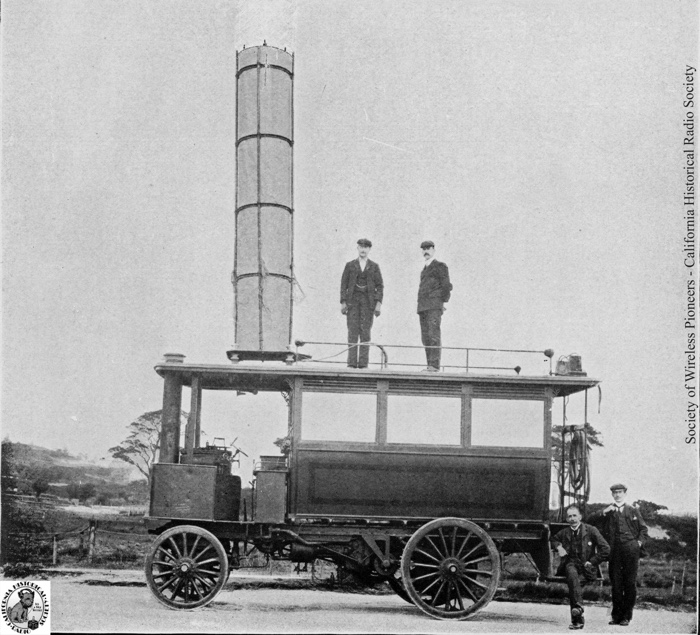

Wireless Telegraph Motor Car used by Marconi (at rear right) in 1901. Society of Wireless Pioneers / California Historical Radio Society, Alameda, California

The focus of the book is mostly the USA, with a few incursions in Europe (mostly France) but the geographical restriction doesn’t prevent it from being immensely enjoyable. It is packed with anecdotes, archive photos and artistic interpretations of the new infrastructures. It will make you stop and look at poles and antennas and will remind you how much digital technologies owe to the technological elements of the 19th century. I was particularly fascinated by Darò’s analysis of how modern telecommunications has developed in relation to the law. What happens when systems of telecommunication infringe on private or public space? How did you navigate between the necessity of the infrastructure and the frictions caused by its use and physical presence? Although their service was considered a public good, these infrastructures were owned by private companies, and they occupied fragments of land, underground space and underwater corridors administered by both private and public legislation. From there, everything was a potential source of conflict: cutting down trees to make room for poles and wires, the ugly and cumbersome “occupation” of the roads by utility poles, the running of wires over a portion of private land, the wires blocking access to buildings in case of fire, the high electrical currents that were a danger to passersby, etc.

My favourite anecdote in the book details how the public phone booth came to acquire the legal status of private space when occupied by a user. In 1967, the FBI discovered that a man named Charles Katz was placing illegal bets from a payphone in Los Angeles. The booth’s telephone was tapped and the recordings were used as evidence. In his trial, Katz argued that the wiretap constituted an invasion of privacy. The Supreme Court, referring to the Fourth Amendment, which “protects people, not places”—and thus the person making the phone should enjoy a “reasonable expectation of privacy.” From that point on, no pay phone could be tapped without a search warrant, making it a popular venue for criminal activity and prompting some U.S. municipalities to establish restrictions on their use.

Christian Marclay, Telephones, 1995

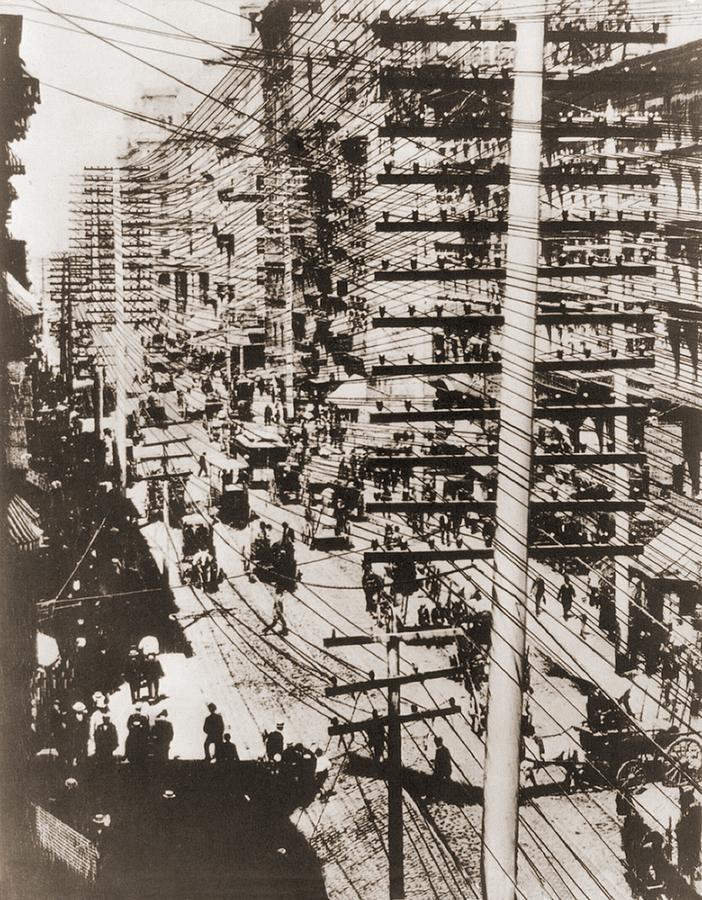

Telephone wires in New York, 1887. Everett Collection, Inc.

Photograph by Walker Evans, View of Morgantown, West Virginia, 1935. Canadian Centre for Architecture, PH1984:0499. © Walker Evans Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Franck Lloyd Wright, The Broadacre City project. Photo by Skot Weidemann

Dutch Harbor Naval Radio Station, Alaska. Photo by George Hanscom, 1915. George H. Clark Radioana Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

Poster advertising the new théâtrophone. Illustration by Jules Chéret, 1896

László Moholy-Nagy, Telephone Pictures, 1922