Three Stations for Art-Science, an ambitious exhibition programme at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, explored the encounter between art, science and society. The project was articulated around 3 exhibitions: The Science of Rome, a historical chapter packed with fun facts, marvellous instruments and famous scientists from Galileo Galilei to Guillermo Marconi; Uncertainty that focused on contemporary scientific research and was imho a bit stiff and confused; T Zero which featured contemporary artworks that investigate and comment on scientific research. That one featured unexpected gems as well as a great mix of disciplines, perspectives and generations. It’s not every day that Agnes Denes shares the space with Ryoji Ikeda, Carsten Nicolai with Giuseppe Penone or Richard Mosse with Albrecht Dürer.

Dora Budor, sforzando, 2017. Collezione Varon | Varon Collection

Exhibition view of T Zero, Tre stazioni per Arte-Scienza. Photo: M3S © 2021 Azienda Speciale Palaexpo

I also found T Zero‘s approach quite unusual: The exhibition followed two main direction. One was guided by the practice of rational knowledge of the reality, mediated by language and by technology. The second one concerned the sensitive knowledge of phenomena. The two threads converged in a third group of works that suggested that reality can be explored through both theoretical abstractions and sensory/sensitive perceptions.

I spent a whole afternoon in the exhibition. There are dozens of works I’d like to write about but I’m going to be modest (or just fainéant) and only mention a couple of them:

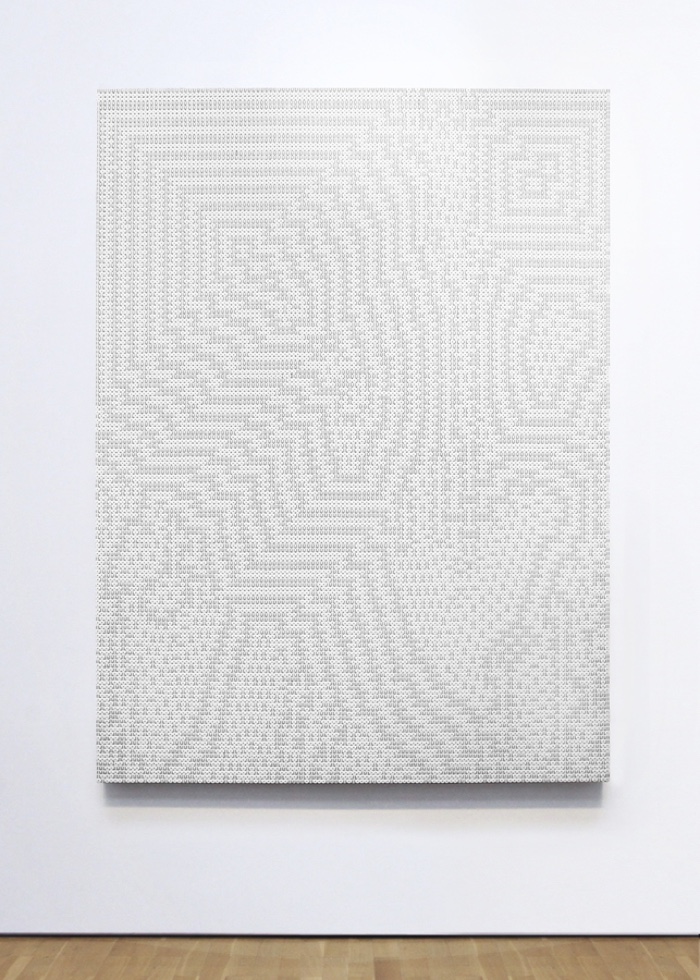

Troika, Reality Is Not Always Probable, 2018

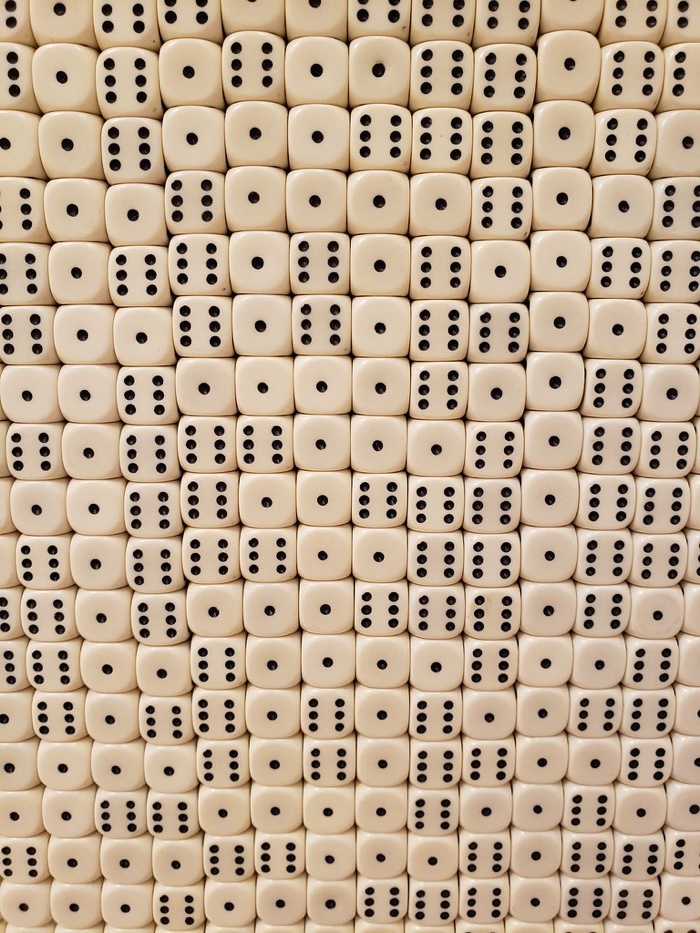

Troika, Reality Is Not Always Probable (detail), 2018

To create Reality Is Not Always Probable, Troika assembled 22,695 white dice by hand. Dice are usually associated with chance and luck. However, by using only two of the six sides of the dice (1 and 6), the artists reduced the probabilistic potential of the system and emulated the rules of a computer binary program.

By simulating digital sequences, the work reflects on how data flows generated by algorithms increasingly influence our reality, as if the complexity of life could be reduced to 1s and 0s.

The roll of the dice relies on the laws of probability and their application to any external activity is a necessarily arbitrary connection, formulated by human action. In contrast, our fate is increasingly determined by algorithms that can come to exist independently from us. Although their developers present algorithms as being objective and rational, the outcome of their decisions often evoke the kind of chance and unpredictability we tend to associate with dice.

The title of the work comes from a quote by Jorge Luis Borges: “Reality is not always probable, or likely. But if you’re writing a story, you have to make it as plausible as you can, because if not, the reader’s imagination will reject it.”

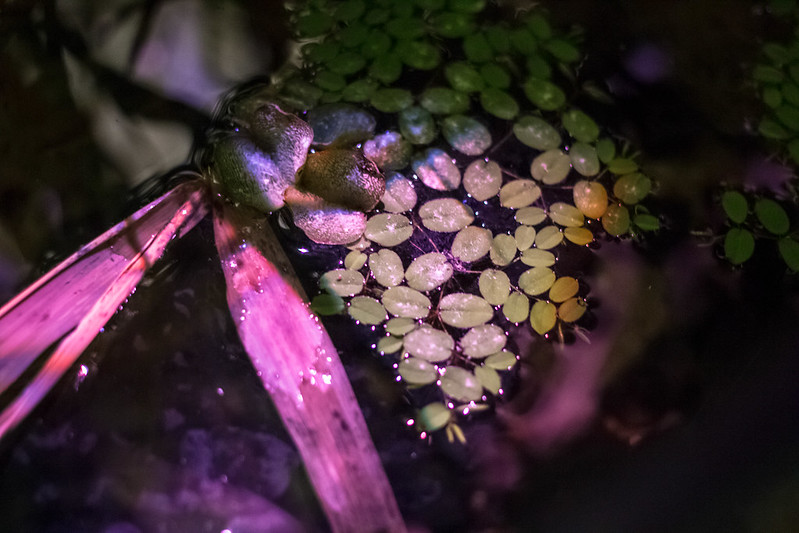

Tega Brain, Deep Swamp, 2018/2021. Photo M3S © 2021 Azienda Speciale Palaexpo

Tega Brain, Deep swamp, 2018 – 2021

Tega Brain, Deep swamp, 2018 – 2021

Tega Brain, Deep Swamp, 2018/2021. Photo M3S © 2021 Azienda Speciale Palaexpo

Deep Swamp is a triptych of aquarium tanks filled with wetland species. Each aquarium is administered by a different artificially intelligent software agent. The agents, called Nicholas, Hans and Harrison monitor their swampy territories and modify the conditions according to their own objectives. Harrison aims for a “natural” looking wetland. Its vision model is trained on thousands of images of wetlands taken off Flickr, so its understanding of what a wetland should be is based on human photography of wetlands. Hans is trying to produce a work of art. It was trained on a data set of landscape paintings from the history of western art. Nicholas simply wants attention. Its dataset favours images of wetlands where humans appear.

Every few minutes, each system takes a photo and assesses how close it is to its goal. Each system will then reinforce the conditions that score the highest in this process, and try new combinations of settings, adjusting the light, water flow, mist and nutrients, to try and engineer their ideal environment.

As territories change under the pressure of climate change, humans are increasingly delegating the management of ecological processes to technologies. Landscape architects Bradley Cantrell, Laura Martin and Erle Ellis identified the paradox within these practices of environmental engineering: reducing human influences on species and ecosystems generally requires growing levels of human management. How much can technology help us curate or optimise wilderness? Can ecosystem be reduced to data sets and models?

Tega Brain’s work questions the perception of the environment as a knowable and controllable system that can be intervened in. “For me, this work is a public invitation to have conversations around the use of these sorts of methodologies,” the artist explained. “What they can and can’t do and what their blind spots are.”

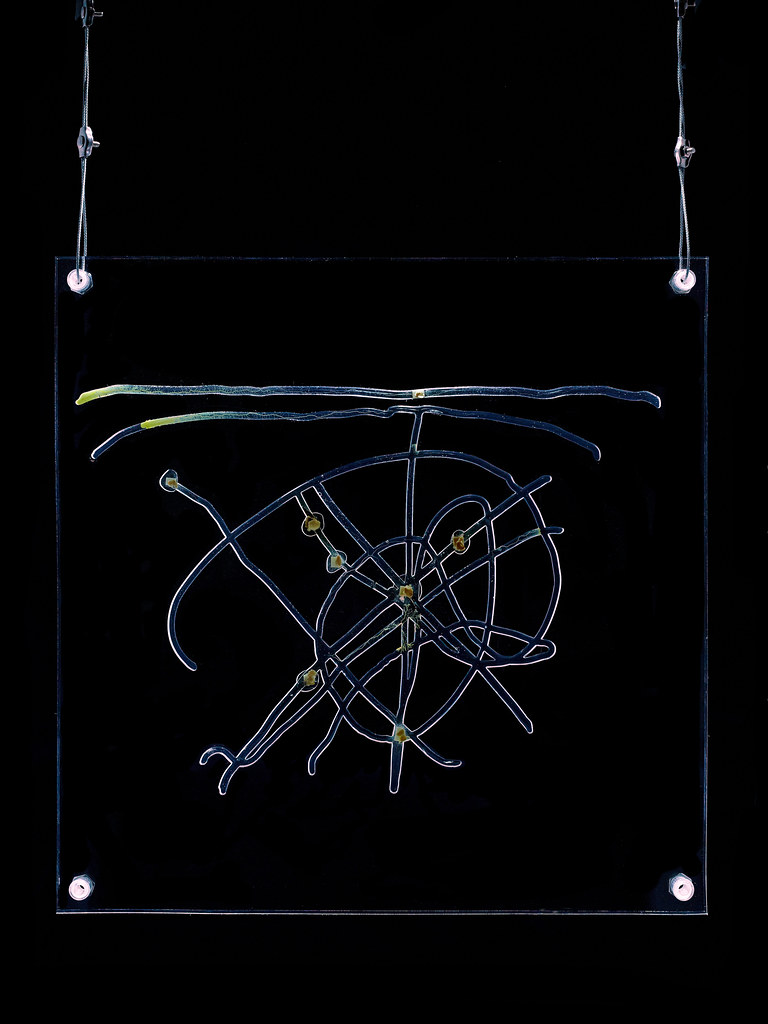

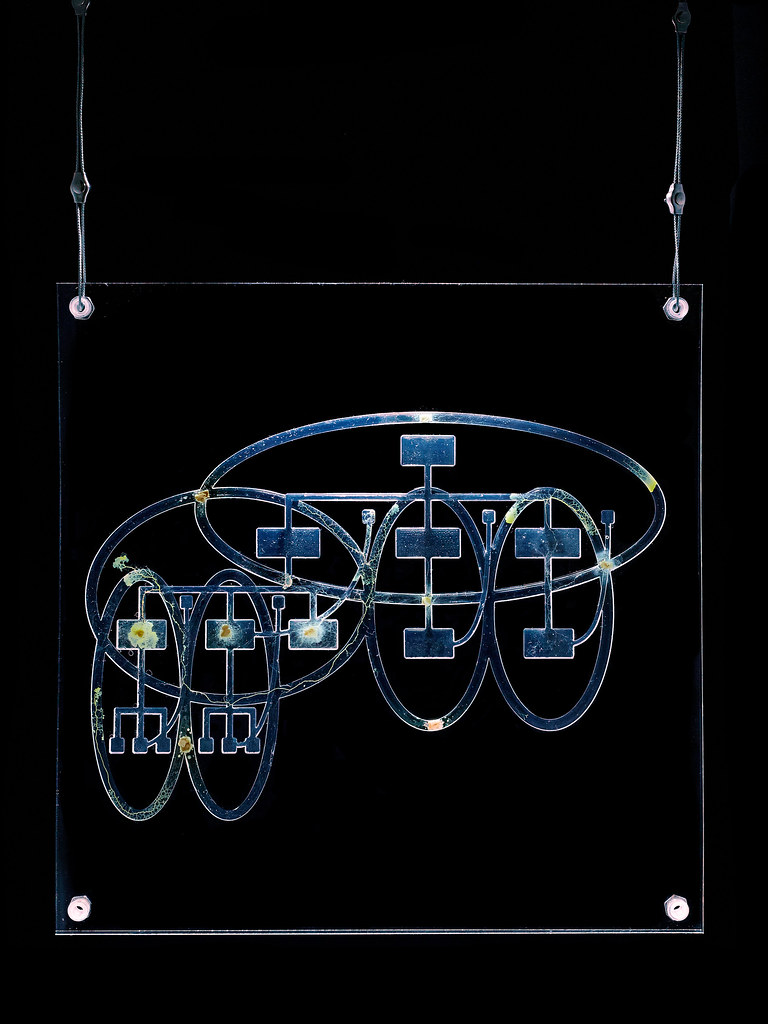

Jenna Sutela, Minakata Mandala, 2017

Jenna Sutela, From Hierarchy to Holarchy, 2017

Jenna Sutela’s works were a collaboration with Physarum polycephalum, the maze-solving blob. The slime mould population of autonomous cells acts as a single being, moving and spreading with efficiency to find food. Though it is devoid of brain, heart or nervous system, the blob demonstrates advanced spatial intelligence, to the point that some scientists advance that the study of the blob behaviour could lead to the design of more efficient, flexible transport networks.

Sutela creates labyrinthine structures for the slime mould to navigate. One of the works shows how it found its way across a maze outlining the shift from hierarchy to holarchy. Another one is based on a mandala drawn by Minakata Kumagusu, a Japanese biologist, naturalist and ethnologist famous for his research on slime moulds.

The navigating capabilities of Physarum polycephalum illustrate the limits of anthropocentrism, celebrate the efficiency of decentralised movements and defy our understanding of intelligence.

Hicham Berrada, Permutations, 2021. © ADAGP Hicham Berrada

Hicham Berrada, Permutations, 2021. © ADAGP Hicham Berrada

Hicham Berrada, Permutations, 2021. © ADAGP Hicham Berrada

Permutations is a series of sculptures in which metals present in obsolete printed circuits design intriguing micro-landscapes. Dipped into electrolytic baths, the mineral compounds from the circuits let matter escape and reorganise into miniature worlds. The resulting metal crystals, which are incredibly fragile, are then solidified by a resin flow, which stops their development at a chosen moment.

In Permutations, matters that looked inert adopt forms that look organic and suggests scenes that we might never experience: outer space territories, deep-sea landscapes, future geological eras. Chemical experiments are framed as sculptures.

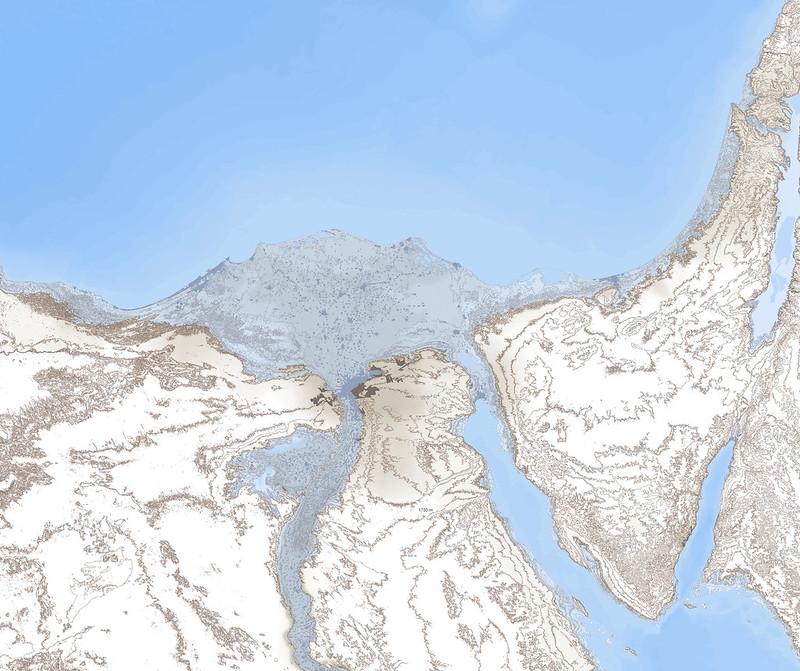

Rüri, Future Cartography X. N-America / The North Atlantic Ocean (detail), 2021

Rüri, Future Cartography X. Middle East / The Mediterranean (detail), 2021

Rüri’s Future Cartography X is part of an ongoing research that invites us to adopt an archaeological approach with regards to that which has not yet disappeared.

These large-scale geographical maps show the shorelines of continents as they will be in a not-so-distant future, when climate change will have redrawn their contours following the drastic rise in sea levels. The incoming changes of the shoreline are based on calculations of the mass of water that will be released during the predicted melting of the Antarctic- and the Arctic ice sheets, the Greenland glacier and all the mountain ice caps of the globe.

The data sets used are in the public domain and are composed from satellite data from various sources. Rúrí collaborated on this project with geographer Gunnlaugur M. Einarsson.

Exhibition view of Ti con zero, Tre stazioni per Arte-Scienza. Photo: M3S © 2021 Azienda Speciale Palaexpo

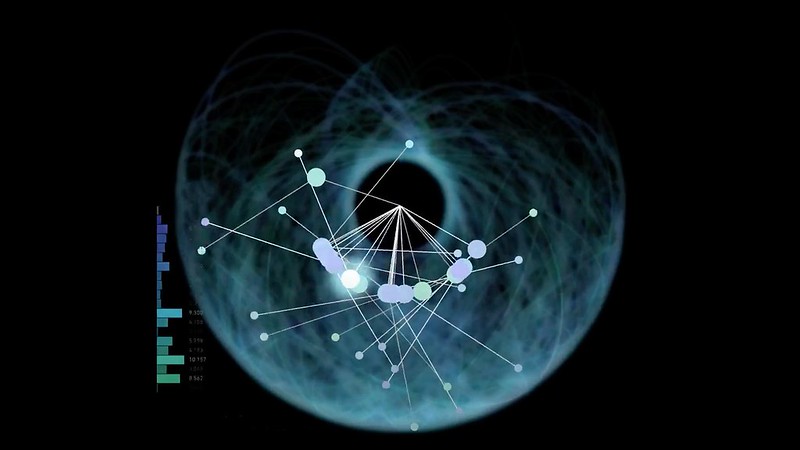

Pierre Huyghe, De-Extinction (still from video), 2014

A navigation through an amber stone, an action frozen in time, an encounter between the organic and the inorganic now and in deep time… Pierre Huyghe’s De-Extinction film magnifies the fossilised plants and insects encased in amber. The artist used macroscopic and microscopic cameras to navigate through the stone and find the earliest known specimen caught mid-copulation 30 millions years ago.

The title resonates with current scientific experiments into the de-extinction of prehistoric species.

More images from the exhibition:

Rachel Rose, Ninth Born, 2019. Photo Marc Domage

Christian Mio Loclair, Narciss, 2018

Exhibition view of T Zero, Tre stazioni per Arte-Scienza. Photo: M3S © 2021 Azienda Speciale Palaexpo

Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, The Wilding of Mars e Pioneers and Descendants: selected generated new subspecies, 2019. Exhibition view of T Zero, Tre stazioni per Arte-Scienza. Photo: M3S © 2021 Azienda Speciale Palaexpo

La scienza di Roma, Tre stazioni per Arte-Scienza, Roma, Palazzo delle Esposizioni. Photo M3S © 2021 Azienda Speciale Palaexpo

La scienza di Roma, Tre stazioni per Arte-Scienza, Roma, Palazzo delle Esposizioni. Photo M3S © 2021 Azienda Speciale Palaexpo

Tavole sciateriche di Athanasius Kircher, Roma 1636. INAF – Istituto Nazionale di Astrofisica, Museo Astronomico e Copernicano, Osservatorio Astronomico di Roma

Athanasius Kircher, Mundus subterraneus, Amsterdam 1664. Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale “Vittorio Emanuele II”, Roma

Incertezza, Installazione Pendolo Doppio 2 c Dotdotdot

T Zero was curated by Paola Bonani, Francesca Rachele Oppedisano and Laura Perrone. The exhibition ran from 12 October 2021 until 27 February 2022 at the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome.