Beijing is the hot city for media art this month. Tonight the Summer Digital Entertainment Jam was inaugurated in a gallery at 798 (the exhibition takes place at Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology), there is the amazing Greenpix media facade and a show which has been dubbed “the biggest exhibition of new media art in the world.” This kind of heavy superlative rubs me the wrong way. The show nevertheless turned out to be an excellent panorama of contemporary media art practice (well, minus my very favourite: activism, China is not exactly big on critics) featuring works easy to understand and engage with even if you’re not a regular of ars electronica festivals. With Synthetic Times – Media Art China 2008, Beijing managed to do what some previous Olympic cities have failed to do (i’m looking at you Torino 2006): taking the Olympics as an opportunity to propose a brave, meaningful, edgy and inspiring art event. I went to the museum twice and was amazed to see so many visitors, from very age range, in the rooms. They were clearly having a good time, asking their husbands or friends to take picture of themselves in front of installations as if these were the Eiffel Tower and laughing all the way while playing with the works.

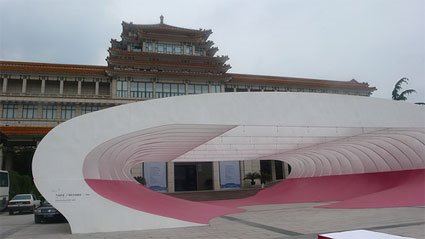

Pneumatic Sound Field, by NOX/Lars Spuybroek and Edwin van der Heide, at the entrance of the museum

Pneumatic Sound Field, by NOX/Lars Spuybroek and Edwin van der Heide, at the entrance of the museum

Synthetic Times – Media Art China 2008 distributes the work of both established and emerging artists around four main themes: Beyond Body, Emotive Digital, Recombinant Reality and Here, There and Everywhere. I had seen many of the projects before but that didn’t prevent me from being delighted to re-discover them in a new context. However, this post will mostly focus on the works i had never

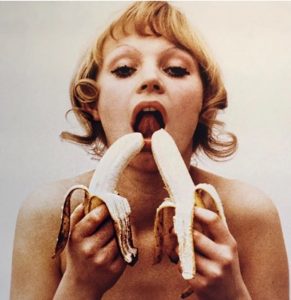

As its title suggest the Beyond Body section explores how artists are adopting electrical, poetical, olfactory or digital paths to extend the physical body. raising questions of subjectivity and the norms of ethical codes.

Sissel Tolaas‘ Fear 9.

Back in 2000, Sissel Tolaas embarked on a projects related to fear. She tracked down 20 men from 20 corners of the word, with different background share one characteristic: they are afraid of other bodies for various reasons. These men were asked to carry a tiny electronic device everywhere with them. Whenever they found themselves in a situation where they were likely to be afraid, the men had to place the device under their armpits. The equipment registered the molecules of the respective sweat. This information was then used to simulate the respective sweat in research laboratories, then microcapsulated.

The microcapsulated sweat smells were then integrated into white sheets of papers placed on the surface of a white wall, without any clear borders. The smell could be released only by a gentle scratch ‘n’ sniff.

The other installation i enjoyed was Jean Michel Bruyère‘s The Path of Damastes. 21 white hospital beds, overhung by 21 fluorescent “daylight” tubes, slowly move and perform a ballet.

Each bed is equipped with an electric scissor jack, which permits a vertical movement of the bed from 38 to 81 centimetres up from the ground. It also disposes of motorized control of positioning of the upper body, which permits a roundabout movement of part of the mattress in the angle values from 0 to 70 degrees. These movements can be executed either simultaneously or independently. The 21 beds are linked together via a MIDI system to a PC which commands and synchronizes its programmed movements*. The beds are also animated individually and together they make a vast choreographical ballet. The numerous variations of creaks produced by the lattice structure under the beds in the effort to lift them compose the very music of the piece and its ballet. The beds are neatly aligned in a circular corridor. Once you enter the corridor and walk, beds keep appearing step after step, it almost seems like it will never end again.

The Emotive Digital chapter engages with ideas of the emotions and the often surprising personality that digital life, machines and interactive devices might be imbued with.

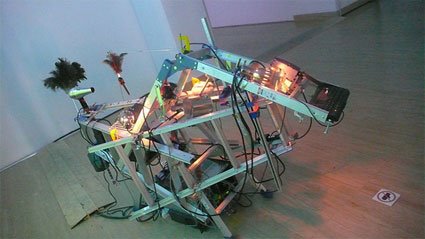

Exonemo (whom Vicente interviewed a while ago) had installed a very successful artwork. Object B VS is a modified first-person shooting game. You are very welcome to play with it and control the action. However, you’ll have to count with a kinetic machine situated on the other side of the screen and assembled from a bunch of household objects, power tools and computer input devices. As wild and chaotic that the machine might seem it does click on the mouse, activate the keyboard and use a pen tablet. Its action hysterically controls an avatar in the game. Try as much as you can, managing to take control over the crazy ugly machine is just a Sysiphean task. The objects’ whimsical actions trigger automatic commands, according to which the game develops.

With Hand Gesture, Wu Juehei explores the way tools shape the way people work and function. Because we spend a lot of time typing on a computer, we got used to a series of “short-cuts” and they came to control our habits of using computers. It is often advised to periodically press (Ctrl + S) in order to save the materials we are working on. Thus, many people would unconsciously press Ctrl + S more than needed without even thinking, as if such action calms their conscious. A simple keyboard had its users forming various and numerous habitual hand gestures.

A keyboard is only a small piece to the puzzle, which kind of new behaviours have came to form part of our unconscious gesture through regular use of the handle of a joy pad, the opening of a cell phone, steering wheel, etc?

My photo set.

The exhibition runs at the National Art Museum of China until July 3.