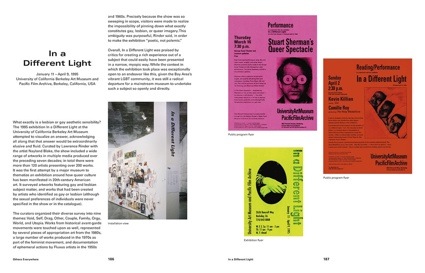

Show Time: The 50 Most Influential Exhibitions of Contemporary Art, edited by writer and exhibition maker Jens Hoffmann. With contributions by Hans Ulrich Obrist, Massimiliano Gioni and Maria Lind.

(available on amazon USA and UK.)

Publisher Thames & Hudson writes: Tracing a history of the field through its most innovative shows, renowned curator Jens Hoffmann selects the fifty exhibitions that have most significantly shaped the practice of both artists and exhibition curators.

The book’s thematic sections focus on a huge variety of exhibitions, including those that have explored public space; reflected on globalization; engaged audiences in revolutionary ways; and brought into the gallery other disciplines such as theatre and architecture.

Short texts introduce and place each exhibition in context, accompanied by installation photographs and factual data about the participating artists, venues, dates, curators and publications, and many feature quotations from the originating curators exploring the premise of the show. The book concludes with a roundtable discussion by some of today’s leading curators.

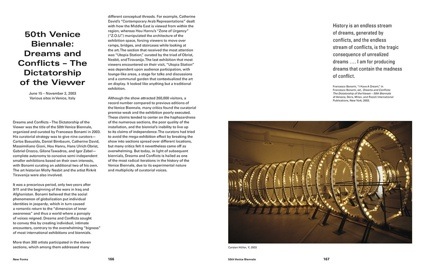

Carsten Höller, Y, 2003. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia – Archivio Storico dell Arti Contemporanee and Air de Paris. Photography: Giorgio Zucchiatti

Carsten Höller, Y, 2003. Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia – Archivio Storico dell Arti Contemporanee and Air de Paris. Photography: Giorgio Zucchiatti

David Hammons, America Street, 1991 (featured in the exhibition Places with a Past: New Site-Specific Art in Charleston)

David Hammons, America Street, 1991 (featured in the exhibition Places with a Past: New Site-Specific Art in Charleston)

Show Time examines the most game-changing and risk-taking exhibitions of the past 30-ish years. The survey begins in the late 1980s when the Cold War ends and globalization takes off.

The book surprised me. I knew i’d find beautiful images, compelling ideas and elegant texts in there and i haven’t been disappointed. But i also thought that Show Time would provide me with a clear confirmation that contemporary art is far too busy contemplating its own navel to question its relevance in today’s society and to engage with a public whose idea of a wise investment does not involve shelling out 32 pounds to enter the immaculate tents of the Frieze art fair. But i was wrong (up to a certain extent) as many of the innovative exhibitions the author selected not only show the evolution of the profession but also a clearer desire to go and meet the public whoever and wherever it may be. Another fairly recent trend in curatorial practice is to cross boundaries, to explore and communicate with other practices such as theater, architecture, literature, science (though i didn’t find any convincing example of art&science exhibition in the book), etc.

The book explores nine themes in contemporary curating:

Beyond the White Cube presents exhibitions that invade public space often with the purpose to meet a public which would not normally be tempted to enter a cultural institution. These are probably my favourite kind of exhibitions as they usually deal more efficiently with social and political engagement and ambition to achieve deeper connections between art and the whole society.

The best example is probably inSITE. Located in the border region between San Diego and Tijuana, the biennial focused on social and political issues related to border control and of course immigration between the US and Mexico. Artists and cultural producers from both sides worked together and the organization usually involved the participation of immigration officers and human rights groups.

Interestingly, Hoffmann notes that while the biennial drew much attention in the press and local public, it didn’t attract the more ‘traditional’ art crowd.

I suspect that inSITE is the most exciting biennial that ever was. Ever timely theme and terrific selection of artists. Here are two of the works created for it:

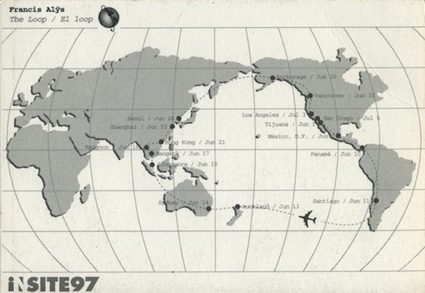

Francis Alÿs, The Loop, ephemera of an action, Tijuana-San Diego, inSITE97, 1997

Francis Alÿs, The Loop, ephemera of an action, Tijuana-San Diego, inSITE97, 1997

In 1997, Alÿs ‘crossed’ the US-Mexico border at Tijuana by plane. He boarded in Tijuana and flew to Mexico City, then to Panama City, Santiago, Auckland, Sydney, Singapore, Bangkok, Rangoon, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Seoul, Anchorage, Vancouver, Los Angeles, and arrived in San Diego a few days later. Alÿs exposed a loophole in Mexico-US border control through a physical loop on a global scale, but in so doing highlighted the fact that this could only be possible for a privileged few.

Mark Bradford, Maleteros, 2005

Mark Bradford, Maleteros, 2005

Mark Bradford’s contribution for inSITE_05 was to give a hand to the Maleteros, the porters who -unofficially- transport luggage and goods between the border of the US and Mexico. Together they worked on a system of maps and signs that promoted their marginalized work alongside that of the labor of policemen, bus drivers and taximen.

Artists as Curators as Artists celebrates artists who intervene through artistic experiments or curatorial work in museum collections as gestures of institutional critique or as a way to use the exhibition as an artistic medium.

In 1992, Fred Wilson collaborated with The Maryland Historical Society to shake up its collection and present Mining the Museum: An Installation. The intervention highlighted museums’ hidden agendas and the silences around certain episodes of the history of Native and African Americans in Maryland.

Fred Wilson, Mining the Museum: Modes of Transport, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, 1992-1993

Fred Wilson, Mining the Museum: Modes of Transport, Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore, 1992-1993

Across the Fields and Beyond the Disciplines. The key word here being (as always) ‘interdisciplinary’. This section of the book explores exhibitions that open up to other fields such as architecture, science and mass media. New methodologies, new ideas, new processes and thus new perspectives emerged from these broader cultural influences.

In 1999, the exhibition Laboratorium turned the whole city of Antwerp (BE) into a laboratory where artists and scientists explored possible common aspects of their working processes. Workstations in the exhibition space enabled visitors to carry out their own experiments while other workstations, distributed throughout the city, worked as laboratories to reflect on specific themes: the laboratory of doubt, a cognitive science laboratory, the first laboratory of Galileo, etc.

Carsten Höller, Key to the Laboratory of Doubt, 2006

Carsten Höller, Key to the Laboratory of Doubt, 2006

New Lands looks at shows that paid homage to the 1989 exhibition Magiciens de la Terre, one of the first group shows to give equal emphasis to art from all over the world. The shows in this chapter therefore take on art from areas of the world as diverse as Eastern Europe and Africa, and that had remained for political, cultural or other reason, under the radar.

A chapter is dedicated to Biennials, the prolific model of exhibition that launches curators’ careers, opens up vast touristic possibilities for cities in search of new energy and serves as meeting point of the international art elite.

While some have merely replicated the biennial model, others have attempted to twist and reinvent it. Manifesta, for example, is ‘pan-European’ and nomadic. Each edition sees the event move to and infiltrate a new city.

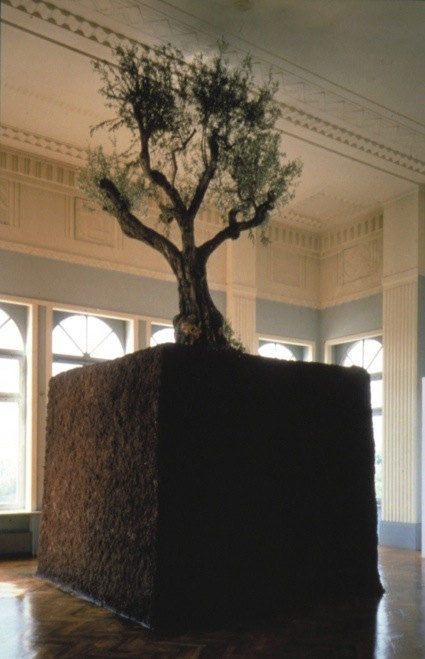

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 1998. Manifesta Luxembourg. © Roman Mensing / artdoc.de

Maurizio Cattelan, Untitled, 1998. Manifesta Luxembourg. © Roman Mensing / artdoc.de

Hans Schabus, ‘Forlorn’ and ‘Another Try for a Room for “Western”‘, 2002, installation view from Manifesta 4, Frankfurt, Germany. Courtesy Manifesta, the artist and the Kerstin Engholm Gallery, Vienna. Photography: Bernd Bodtländer

Hans Schabus, ‘Forlorn’ and ‘Another Try for a Room for “Western”‘, 2002, installation view from Manifesta 4, Frankfurt, Germany. Courtesy Manifesta, the artist and the Kerstin Engholm Gallery, Vienna. Photography: Bernd Bodtländer

New Forms looks at attempts to rejuvenate or even overthrow well-known exhibition formats and processes. (Is it me is this starting to get a bit repetitive?)

For example, An Unruly History of Readymade applied the principles of the readymade to the making of the exhibition (which was obviously about readymade artworks.) The show was held in the largest juice-production factory in Mexico. Stacked artworks and pallets of juice stood side by side.

An Unruly History of Readymade

The chapter Others Everywhere deals with shows that explore race, sexuality, class, gender, nationality. Phantom Sightings: Art After the Chicano Movement, for example, embraced the Chicano movement and the more experimental art that comes with and out of it. The movement, which emerged in the 1960s and 1970s, encouraged political empowerment and ethnic prides over issues such as civil rights or immigration.

Gary Garay, Paleta Cart, 2004. Courtesy of the artist, © Gary Garay

Gary Garay, Paleta Cart, 2004. Courtesy of the artist, © Gary Garay

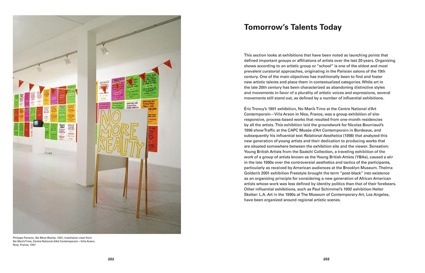

Tomorrow’s Talents Today presents exhibitions that, by placing artists under new categories, have been formative to certain artist groups or affiliation. Nicolas Bourriaud’s show Traffic and his text about relational aesthetics is probably the most discussed example. As was Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection which gave us/made up the YBAs.

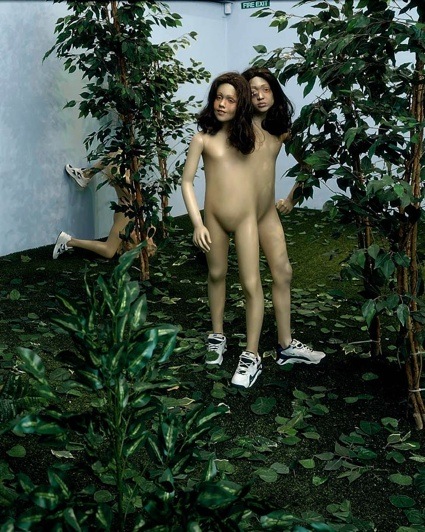

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Tragic Anatomies 1996

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Tragic Anatomies 1996

The last chapter, History, presents exhibitions that set a new art-historical agenda through a greater consideration of female and non-Western artists and underrepresented art forms such as performance and conceptual work. I’m sad to read we still see ‘female and non-Western artists’ as separate categories in need of special attention.

That’s for the ‘more socially-engaged than expected’ content. Now for the form: Show Time features the slick images that define art books nowadays. It is also doing a great job at not being too heavy on the art jargon. I wouldn’t say that this is a book for a public that has zero interest in contemporary art but it does help making it more approachable, easier to read and experience. It also definitely puts the whole curatorial practice into a more challenging and ‘challengeable’ perspective

I hope the intro to the review doesn’t me sound like a bitter, ever-discontented gallery-goer. I do love contemporary art but i’ve been almost traumatized by the aloofness some of the major art shows and fairs i’ve seen recently. The book made me realize that i should just be more selective and see better exhibitions.

Philippe Parreno, No More Reality, 1991, installation view from No Man’s Time, Centre National d’Art Contemporain–Villa Arson, Nice, France, 1991. Courtesy the artist, Villa Arson, Nice, and Air de Paris, Paris, © Jean Brasille/Villa Arson

Philippe Parreno, No More Reality, 1991, installation view from No Man’s Time, Centre National d’Art Contemporain–Villa Arson, Nice, France, 1991. Courtesy the artist, Villa Arson, Nice, and Air de Paris, Paris, © Jean Brasille/Villa Arson

I’ll close the review with a sentence Hoffmann wrote in the introduction of the book: “Show Times includes very few museum shows from the United States, which is perhaps an indication of a general lack in curatorial innovation in the American art world, cuts in public funding, increase in private interests, or all of the above.” I don’t think the problem is the lack in curatorial innovation, i’d rather believe that slashed funding for culture and increasing mingling of private sponsorship is to blame. Take note, Europe! We are well on our way to meet the same under-funded, risk-phobic fate.

Views inside the book: