A review of the book Becoming Geological, edited by programmer, writer, performer, artist and explorer Martin Howse. Published by V2_Publishing.

Humankind has always been dirty and harshly geological, through intentional incorporation of earthly and thus cosmic elements (as part of medicinal or spiritual practices), and within a direct connection with a slowly changing earthly and cosmic environment. The earth authors us.

Some 2500 years ago, Greek philosopher Empedocles stated that all matter was made of different combinations of four elements: air, fire, wind and earth. Becoming Geological asks the reader to not just focus on our earth component but to become earth and also cosmic and metal. Embracing our geological existence might seem absurd at first but if you think about it, our bodies already contain metal elements, naturally or not: the iron in our blood, the dental fillings, titanium hip replacement, the zinc pills some of us took in the hope that it would ward off the coronavirus, the kidney stones, etc. And then there’s the insidious metal we inhale, the anthropogenic indicators we breathe in and out: the compounds of human-made materials released when forests burn, the isotopes from nuclear testing, the metallic dust from mining sites, etc. Could we extract those metal elements from our own bodies and put them to good use?

Over the course of a series of workshops, the Tiny Mining community attempted to do just that. They explored how to mine precious and rare earth minerals from within their own bodies. The book is inspired by their research, experiences and experiments. It aims to guide us and help us embrace our geological essence and live within new planetary and cosmic techno-cycles.

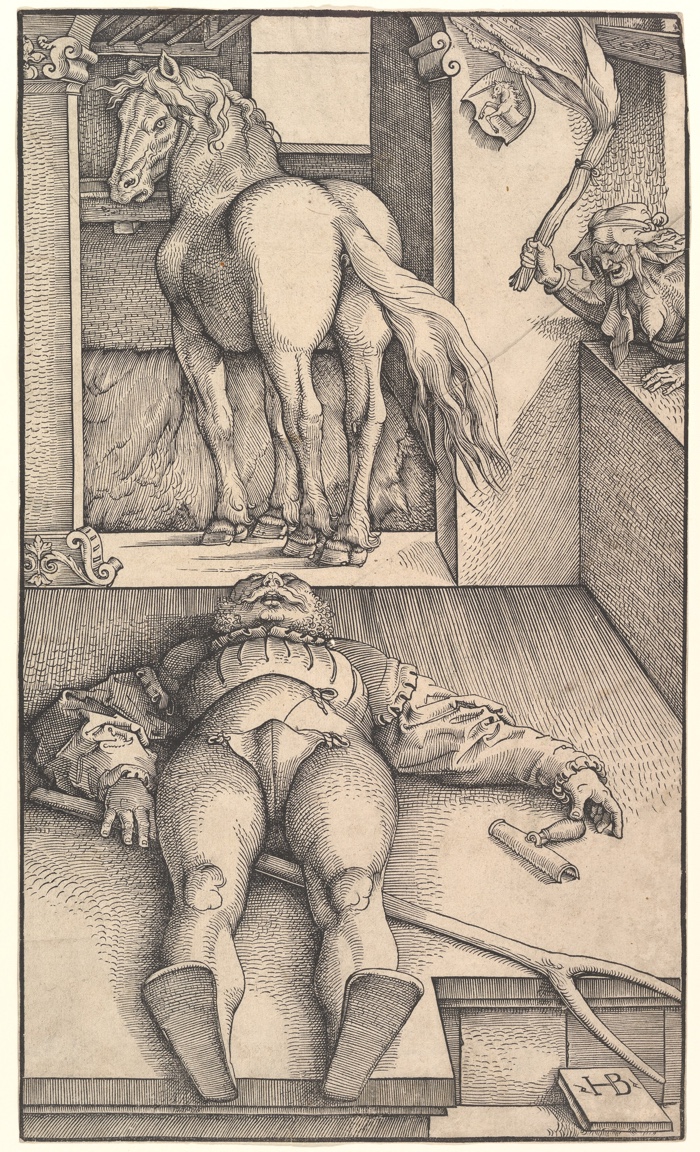

Hans Baldung Grien, The Bewitched Groom, 1544

Anaïs Tondeur, Mourning the infinite, 2022

I immensely enjoyed this book and wish I could visit the exhibition it accompanies. Even though there is something utterly bizarre about the idea of “becoming metal, becoming earth and becoming cosmic,” I found the thinking exercise so challenging that I now look at life, the world, myself differently. In a way that I never have despite the countless conferences, books and exhibitions I’ve attended that urge us to (re)connect with the living -mostly plants and animals. Perhaps because there is something singularly sincere, intimate and meaningful, something less performative in what I perceive from the Tiny Mining practice. Or perhaps because its ideas and ethics took me so much by surprise when I first heard them that they still haunt me. The main reason why I’d recommend the Becoming Geological book though is the variety of perspectives on Tiny Mining it presents. The editor, Martin Howse, asked philosophers, artists, geologists, anthropologists, volcanologists and other thinkers what becoming geological means for our sense and our ethics. Here are a few words about some of the essays I enjoyed the most:

Reflecting on the Tiny Mining “sweatshop”, Agnieszka Anna Wołodźko, a lecturer and researcher at AKI Academy of Art and Design ArtEZ, notes how, in their narratives, the members presents the human as the radical other to the non-living earth. By doing so, they follow the capitalist logic of the radical difference between what is human and what is considered as Nature, positioning the human outside the logic of co-relation and dependency. However, as the Tiny Mining practice of mapping the co-relation of the moon with their metal harvest suggests, human bodies are objects of planetary manipulations. Observing the movements of planetary bodies will lead to a deeper understanding of human bodies. We don’t need Elon Musk to be a multi-planet species.

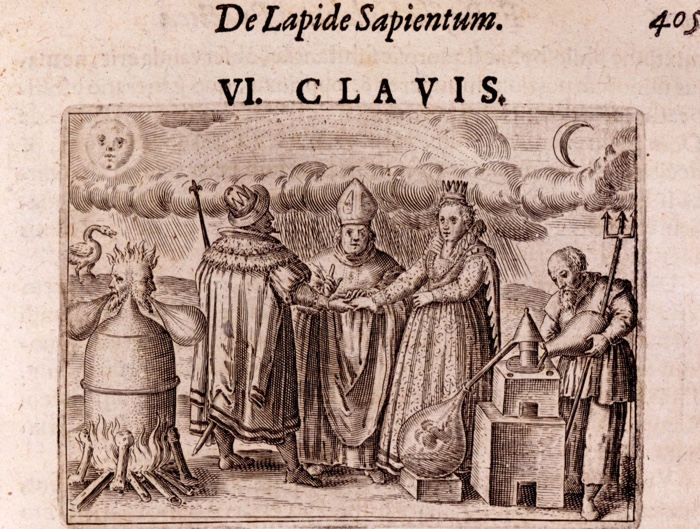

Matthäus Merian the Elder, VI. CLAVIS, The sixth key, The Twelve Keys of Basil Valentine, Basil Valentine, 1678

Cecilia Jonsson in collaboration with Dr. Rodrigo Leite de Oliveira, Haem, 2016

Anthropologist Aaron Parkhurst reflected upon the contribution that the Tiny Mining practice offers to debates within anthropology, and medical anthropology more specifically. “When minerals and metals are extracted from the body, how does it change the social constitution of those minerals?”, he asked. “What new ethics does it open upon the people who take part?” His reasoning was based on the Tiny Mining experiments but also on two facts. The first one took place during the Holocaust when Heinrich Himmler gave the SS orders to collect gold teeth from individuals who died in death camps. The gold was melted down and added to national gold stocks, and then traded to the Swiss national bank. The social life of bullion in Europe after the war, Parkhurst concluded, is thus still tainted by the immense tragedy suffered by the unnamed dead and their families. Such social lives of minerals still shape political, cultural and economic relations. The second example he gives about this deep connection between minerals and human life is related to the ISS Urine Processor Assembly which converts human urine and flush water into potable water. The initial operations failed due to the excess calcium excreted by astronauts due to extreme osteopenia associated with microgravity living.

For the anthropologist, Tiny Mining is a thought experiment that speculates on a future ecology that might be tied more intimately to the cycles of consumption and production that sustain the body and the community.

Rosa Whiteley, Pollution Allures

In his essay, Michael Marder, Ikerbasque Research Professor of Philosophy at the University of the Basque Country, UPV/EHU, Vitoria-Gasteiz, connected and contrasted two ways of becoming geological today. The first is the gradual decomposition of a corpse into the earth from which it eventually becomes indistinguishable (even though the mysteries of modern life can sometimes slow down the decomposition process.) The second involves the by-products of industrial techno-bodies, encrusted in geological strata, as well as, in the shape of microscopic fragments or nanoparticles, in the lungs and other tissues of all that lives.

Philosopher Patricia MacCormack‘s sharp and perceptive essay denounces our “exclusionary anthropocentrism” and the harm that what Carol Adams calls the ‘arrogant eye’ of human exceptionalism is doing to the other sentient species and to the Earth in general. “We are civilised when it suits us, and biological imperatives when it excuses us,” MacCormack writes.

Tiny Mining, for the philosopher, fits into a scenario in which humans are becoming resources for unknown life, in which we can be utilised as a part of the many strata of the Earth. This willingness to become strata for the Earth, however, does not reverse our power from imperator to ‘victim’.

The six artists who participate in the Becoming Geological exhibition at V2_ also contribute to the book with texts that consider the intimate connections between technological, planetary, cosmic and earthly bodies.

I was particularly fascinated by Alfonso Borragán‘s piece about the enthusiasm, among the elite of the 16th and 17th century, for bezoar stones. They would ingest these body stones for their purported magical and medicinal qualities. Bezoars are enteroliths, mineral concretions or calculus sometimes formed in the gastrointestinal system of ruminants. In order to find only one, sometimes 100 animals had to be killed.

Previously: Tiny Mining. Extracting minerals from our own body, Interview with Cecilia Jonsson, the artist who extracts iron from invasive weeds, An artificial planet made entirely of human bodies.

Becoming Geological, curated by Martin Howse and Florian Weigl, remains open at V2_, Lab for the Unstable Media, in Rotterdam until 8 January 2023 (the exhibition is closed in the period from 24-12-2022 until 4-1-2023.)