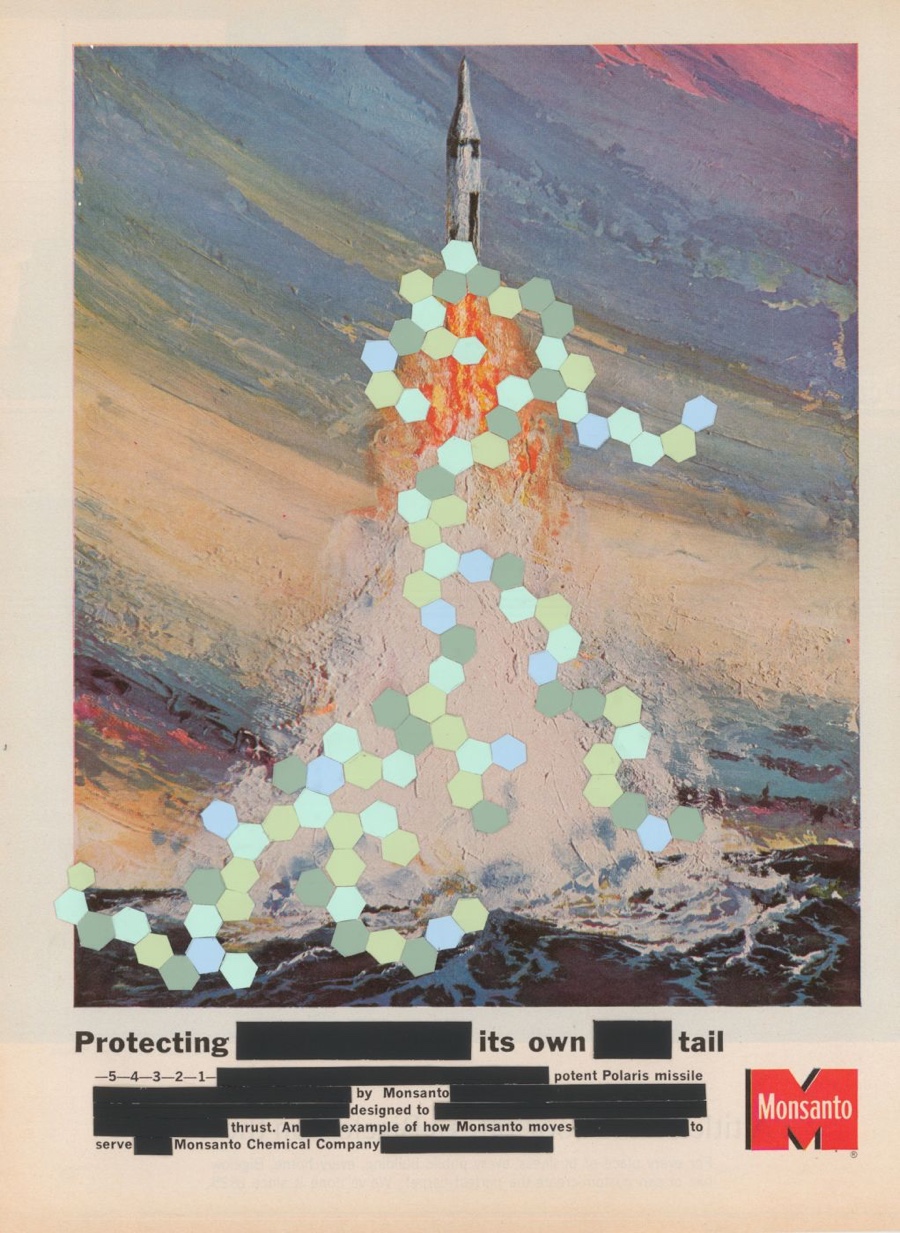

Kirsten Stolle, Protecting Its Own Tail (from the series Monsanto Intervention), 2013. Collage on a 1963 Monsanto magazine advertisement

Pharming, or pharmaceutical farming, uses genetic engineering to insert genes into host animals or plants so that they produce substances that may be used as pharmaceuticals. The process allows the production of cheaper drugs on tap. “If you need more, you breed more,” a spokesman for a pharming company told the NYT back in 2009.

Unsurprisingly, the technology is controversial, especially when it comes to animal welfare. These are animals genetically engineered for the sole purpose of serving as pharmaceutical factories, as if they were walking and breathing manufacturing plants rather than sentient creatures.

There are other concerns as well: the animals could suffer, their germs contaminate the drug, the animals could escape and breed with others, spreading the gene with unpredictable direct and indirect consequences, offspring of transgenic animals have been born with abnormalities, etc.

Animal pharming might sound like bad science fiction to many of us but it is already a growing business. In 2009, the FDA approved the sale of the first drug produced by goats genetically engineered to secrete the protein Antithrombin in their milk. The compound is then used to create anti-clotting drugs for by patients with a rare blood disorder. Since 2009, other animals have been genetically modified to produce medications needed by human.

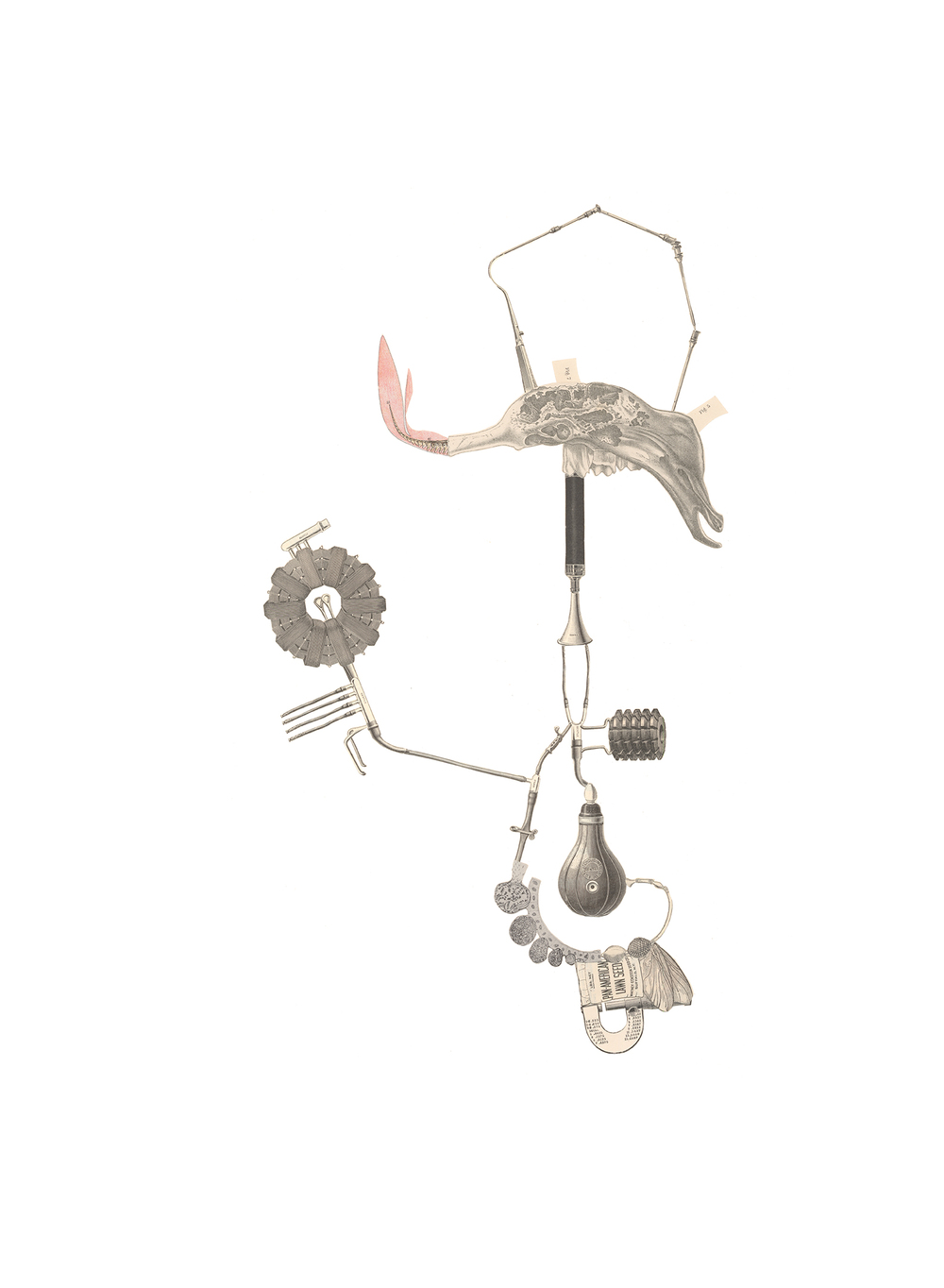

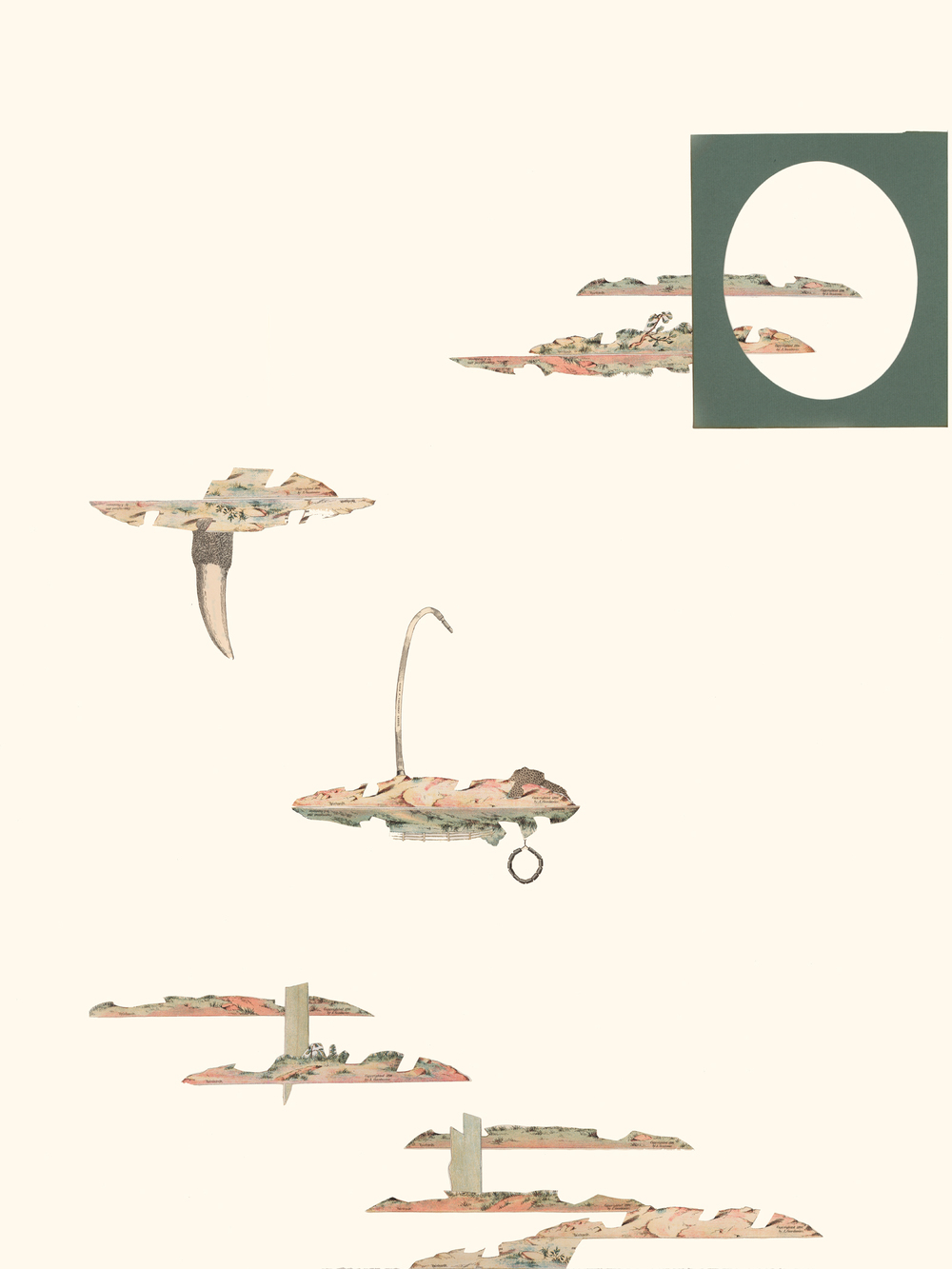

Kirsten Stolle, AP 10 (from the series Animal Pharm), 2014. Collage on paper

The practice hasn’t been much analyzed and debated in the mainstream press but artist Kirsten Stolle is inviting the public to reflect more closely on this new use of genetic engineering with a series of collages titled ANIMAL PHARM. Bearing a title that evokes Orwell’s allegorical novella Animal Farm, the intriguing and delicate collages comment on the insidious connections between greedy corporations, complicit governments and public health (as well as the well being of other living creatures.)

Animal Pharm is part of Stolle’s broader investigation into industrial food and drug production and the lack of transparency and governmental oversight that surrounds them. The artist is currently having a solo show at NOME gallery in Berlin. The exhibition presents not only the Animal Pharm series but also Monsanto Intervention, a group of collages about the biotechnology corporation that poisoned the environment with its Agent Orange, floods the world with genetically modified crops and pollution, bullies small farmers to protect their seed patents, and is now attempting to portray itself as the spearhead of the green revolution built around “sustainability”.

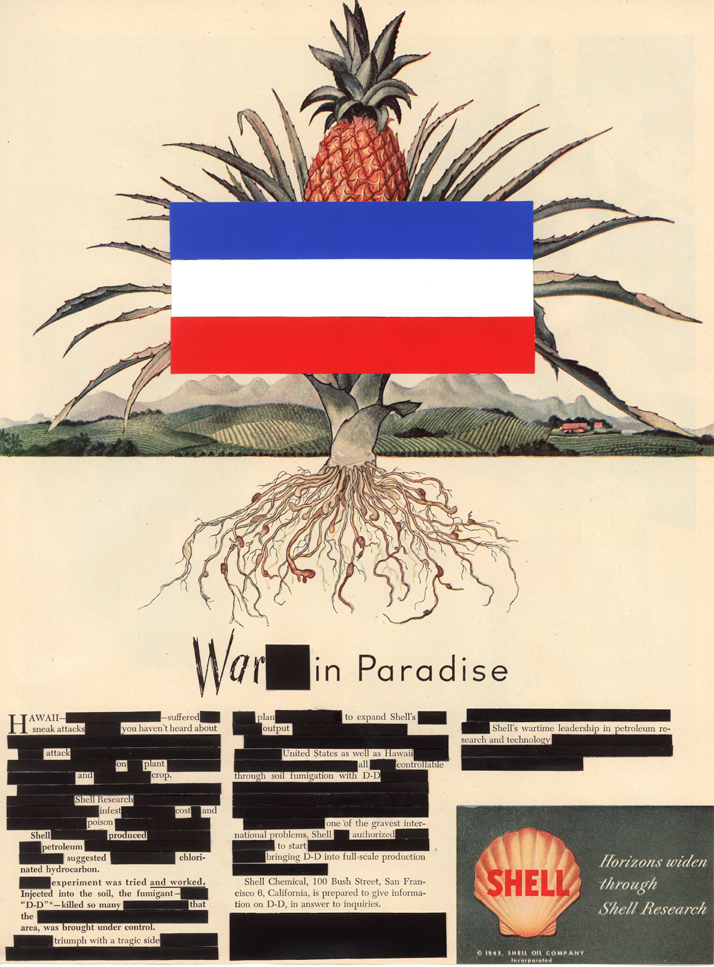

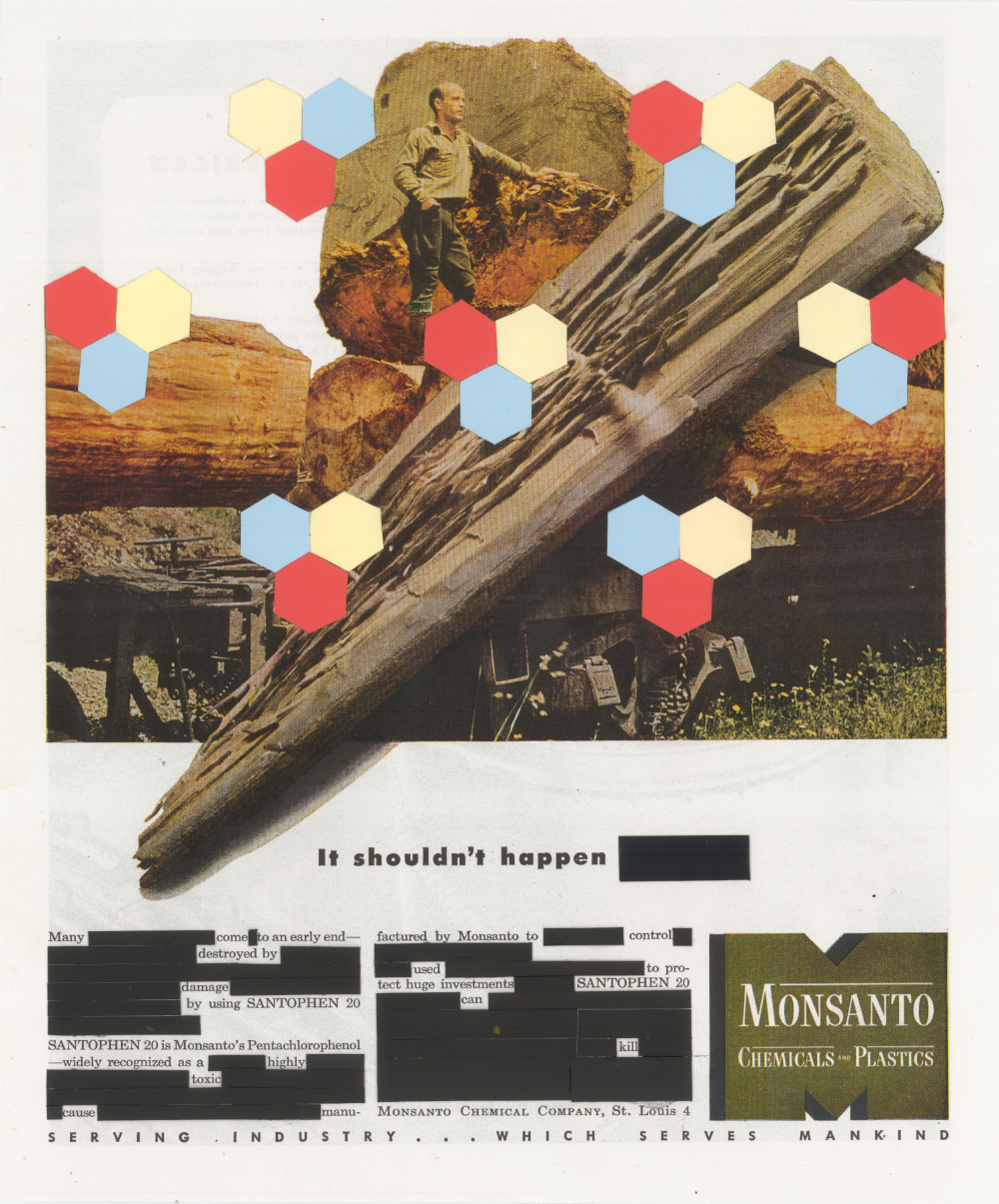

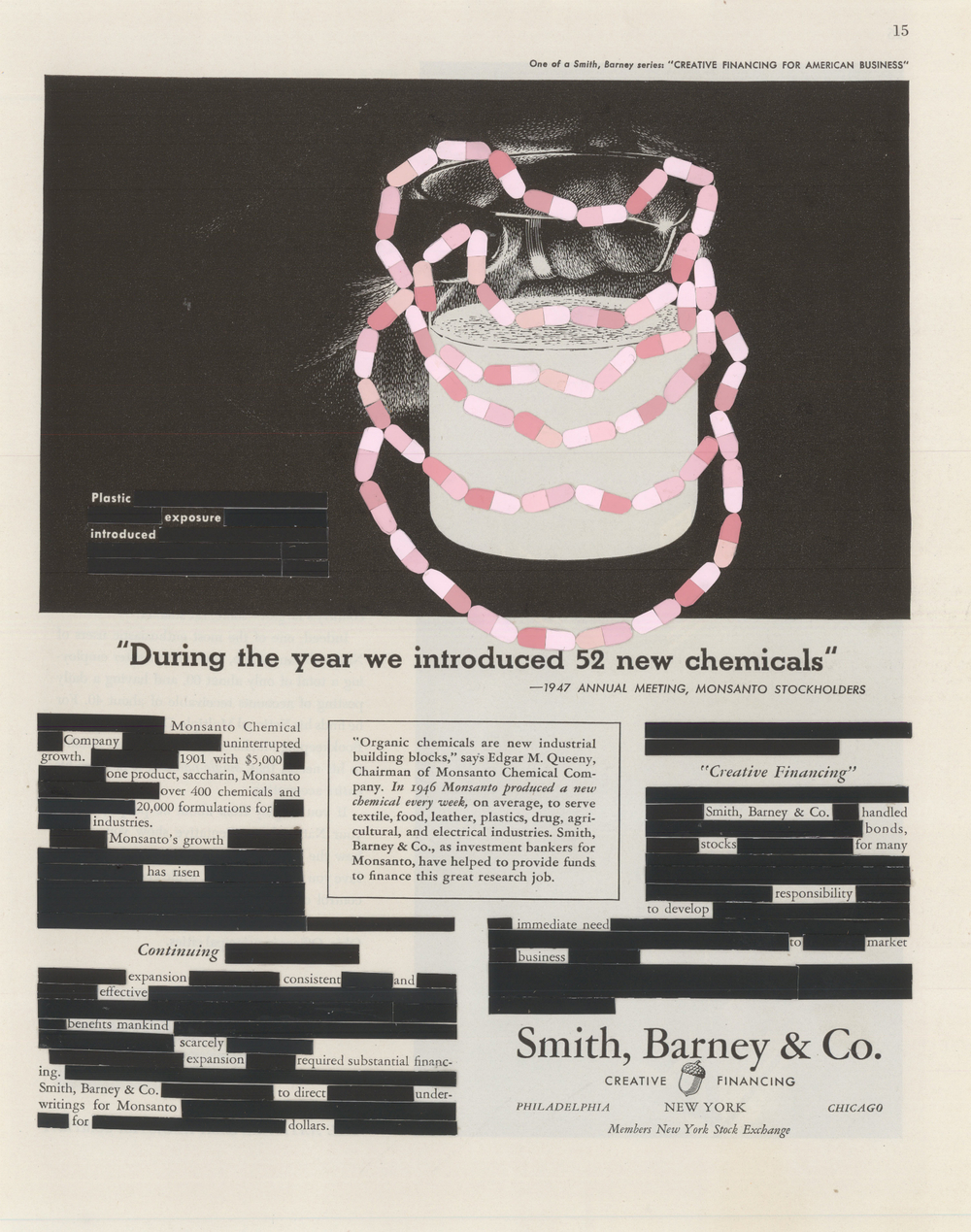

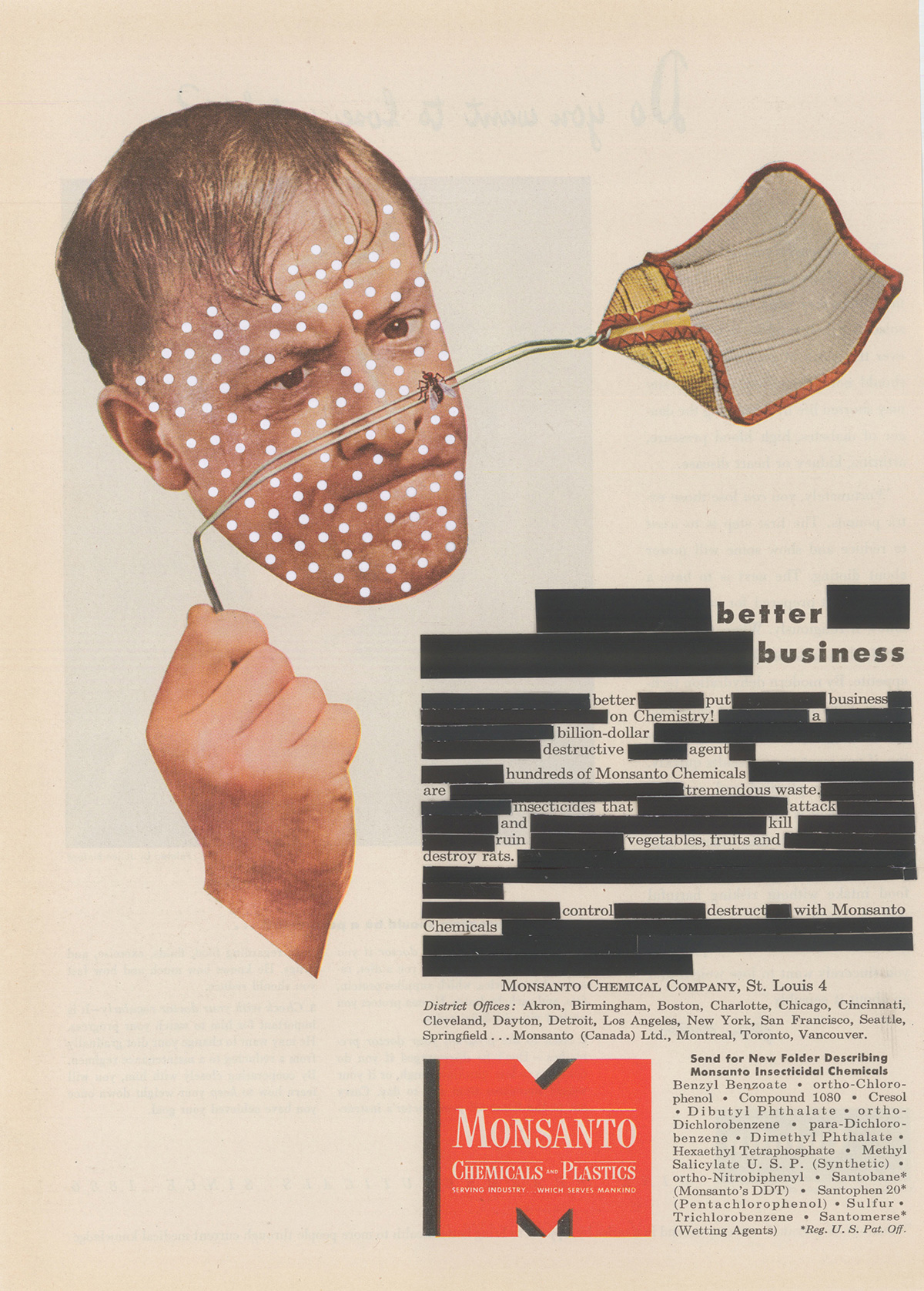

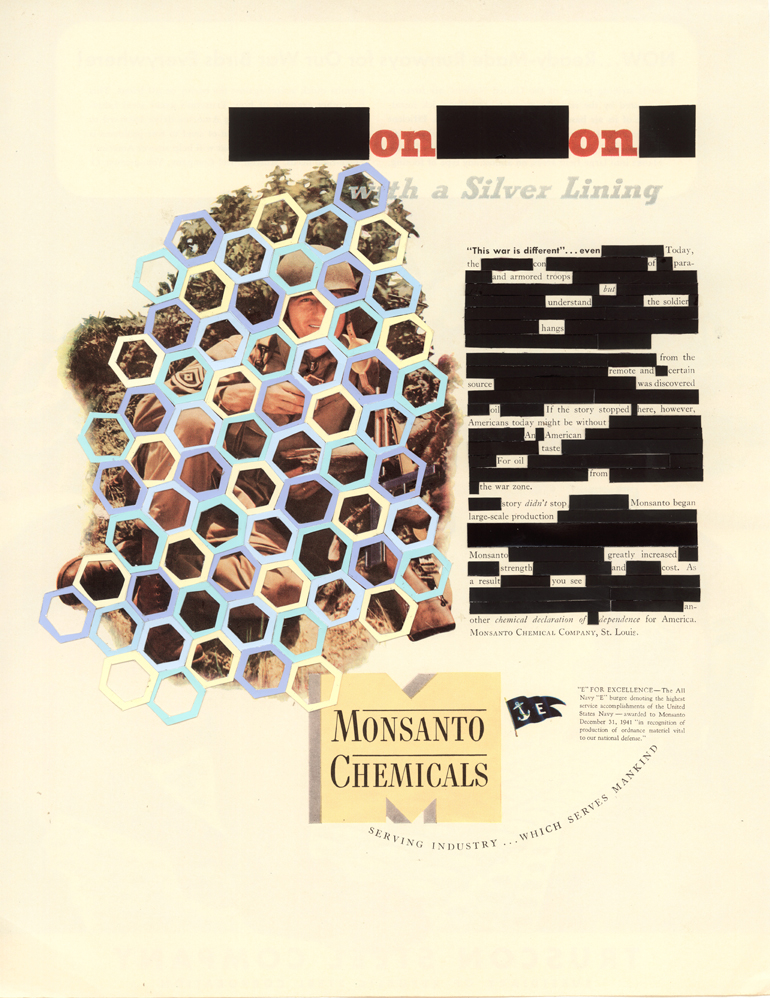

In Monsanto Intervention, Stolle submits the advertisements that the GM giant bought in 1940s-1960s magazines to collage, cuttings and drawings that subtly but efficiently brings the original propaganda into a more truthful but also sinister light.

I caught up with the artist as she was flying to New York where her work is part of Evidentiary Realism, an exhibition that opened a few days ago at Fridman Gallery.

Kirsten Stolle, War In Paradise (from the series Monsanto Intervention), 2013. Collage on 1945 Shell magazine advertisement

Kirsten Stolle, It Shouldn’t Happen (from the series Monsanto Intervention), 2013. Collage on 1947 Monsanto magazine advertisement

Hi Kirsten! The issues addressed in Animal Pharm are quite disturbing. The series looks at the use of genetic engineering to produce pharmaceuticals within host animals. How much is that pharmaceutical research still confined into labs? How much of its results is already available at the chemist now? Are we already buying some of that without even realising it?

Most drugs produced within genetically engineered (GE) animals target specific rare or specialized diseases, and are given in consultation with a patient’s doctor, not through a general pharmacy. In 2009 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved and released guidelines for the commercialization of genetically engineered/transgenic animals. This included approval for the first transgenically derived drug, the human anti-clotting protein antithrombin (manufacturer name ATryn) in the milk of genetically engineered goats. Historically, the protein has been extracted through human blood donation and is time-consuming and highly regulated. Using GE animals to produce drugs more quickly, and with perhaps less oversight and regulation is attractive to the pharmaceutical companies.

Pharmaceutical companies and universities continue to actively pursue drug trials in genetically engineered animals. Creating drugs within animals brings up a wide range of moral and ethical questions and propelled me to examine “pharming” through my project Animal Pharm. Issues related to animal welfare, breaching species barrier for economic benefit, and the implications of patenting potential new forms of life are considerable. As a society, the ethical and social concerns, along with the unintended consequences of this experimental science need to be fully transparent, further investigated and brought to peoples’ attention.”

Kirsten Stolle, AP 8 (from the series Animal Pharm), 2014. Collage on paper

Kirsten Stolle, AP 6 (from the series Animal Pharm), 2014. Collage on paper

It seems that you research the issues your work exposes quite thoroughly so i was wondering if you could share some of that research and help us make better-informed food and health choices. Could you recommend books, videos or any online material we could have a look at if we want to know more about the pharming business?

For overall contextualization of the historical impacts of pesticides/herbicides I’d recommend the book Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. A terrific documentary from 2008 titled The World According to Monsanto is very compelling and maddening. In Defense of Food by journalist and activist Michael Pollan. For in-depth reading, the monthly peer-reviewed science journals Nature and Nature Biotechnology offer research backed articles. Organization such as the Environmental Working Group, Union of Concerned Scientists, Organic Consumer Association, Center for Food Safety are terrific watchdog and advocacy organizations.

Marie-Monique Robin, The World According to Monsanto, 2008

How didactic and self-explanatory do you think your final pieces need to be? Do you feel that the message has to be crystal clear or do you prefer to leave space for the viewer to reflect and speculate?

My intention is to develop work that engages the viewer visually and intellectually without being overly didactic. The themes I examine in my work are contemporary concerns and most people will find some connection to the issues. Although my projects have a particular critique in mind, giving the viewer space for an ambiguous reading or even an opposing view can create interesting conversations.

Kirsten Stolle, 52 New Chemicals (from the series Monsanto Intervention), 2013. Collage, 1947 Smith, Barney and Co. magazine advertisement

Kirsten Stolle, Better Business (from the series Monsanto Intervention), 2013. Collage, punched holes, 1947 Monsanto magazine advertisement

Some of the works from your series Monsanto Intervention will be part of the exhibition Evidentiary Realism which opens on 28 February in New York City. The series documents and reframes magazine adverts that Monsanto published in the 1940s-1960s to market their toxic chemicals for use in war, agriculture, and home. The name Monsanto equals “Big Satan” in Europe and I know of many American initiatives that attempt to counter its influence but i don’t know how widespread the anti-Monsanto feeling really is in the U.S. But how much awareness of the evils of Monsanto is there in the U.S.?

Monsanto uses sophisticated propaganda to position itself as a sustainable agriculture company, greenwashing its 100 + year history as a chemical company. They spend hundreds of millions of dollars on campaigns to defeat anti-GMO legislations and create highly produced radio and TV commercials targeting consumers with a “Monsanto feeds the world” message.

When it comes to food safety, some of the US population believes the government acts as a watchdog over chemical companies like Monsanto, and works to protect us from unhealthy and dangerous substances. But with the continued revolving door between chemical company CEOs and government officials, the line is profoundly blurred between the regulator and the regulated. Additionally, increased food borne illnesses, monthly food recalls and environmental issues associated with herbicides/pesticides, have lead to a growing skepticism of our government interests.

Due to the efforts of advocacy groups and some legislators, there has been increased awareness of GMOs over the past several years. It has taken rigorous work to educate the public on exactly what genetic engineering of plants and animals means, and subsequently how GE impacts our national and global food system. The agrichemical corporations have a huge lobbying presence in Washington DC and spend millions on disinformation and greenwashing. In the US Monsanto is most closely associated with GMOs and there have been nationwide “March Against Monsanto” rallies and protests. In context with our industrialized food system, the proliferation of GMOs has raised additional concerns about corporate profit over human, animal and environmental health.

In Europe we feel we are protected from GMOs food and crops. Do you feel that we are naive? Have you during your research process encountered signs that Monsanto influence and products are present in some form or other in Europe?

I am very interested in how other countries treat/accept/deny GMO products or the growing of GMO plants. I am not familiar enough with how Agribusiness pushes to get their products into the EU market, although I understand there has been strong resistance from citizens and governments within individual EU nations. My sense is that the chemical companies have mainly focused their attention elsewhere, primarily on the US and developing nations where regulatory barriers and resistance is lower. In the US we have no federal regulations on GMOs (GMO ingredients are prohibited in organic foods) and developing countries are fed the narrative that GMO seeds and accompanying herbicides will increase crop yields to impoverished nations.

Kirsten Stolle, This War is Different (from the series Monsanto Intervention), 2013. Collage on 1942 Monsanto magazine advertisement

Kirsten Stolle, By The Ton, 2013, collage on 1957 Monsanto magazine advertisement

The issues your work engages with are so wide-ranging, so complex and overwhelming, it must be intimidating to try and address them. I’m also expecting that the new U.S. government will not rush to solve any of those problems. This is probably a question you’ve been asked countless times but what do you think is the role of art in trying to visualise, communicate, resist or otherwise help disentangle all this mess?

Artists, and by extension their work, are essential to the cultural system particularly during challenging political times. Artists who strive to make socially-conscious art are most successful when something new can be added to the existing narrative and the conversation moves forward to the point of encouraging critical thinking. Socio-political art, whether provocative or relatively quiet, is always grounded in direct critique. Because my work is underpinned by topics that have a political framework and hit upon relevant social issues, my work can be challenging and uncomfortable. My focus is to observe and creatively reflecting back what is often too scary or daunting to witness.

Looking at your portfolio, it seems that your earlier works didn’t reflect your sociopolitical concerns so explicitly. Why this shift in your practice?

Yes, my early work centered on creating abstractions based on natural and human forms, using printmaking and mixed-media as my primary media. I was politically active during that time, but my art practice and political life remained somewhat separate. It was not until I began to experience health issues with soy products and to research GMOs, that I began to shift into making work based on my health and political concerns. Since 2010, my art practice has deepened into a platform where I can research and develop work within a visual vocabulary.

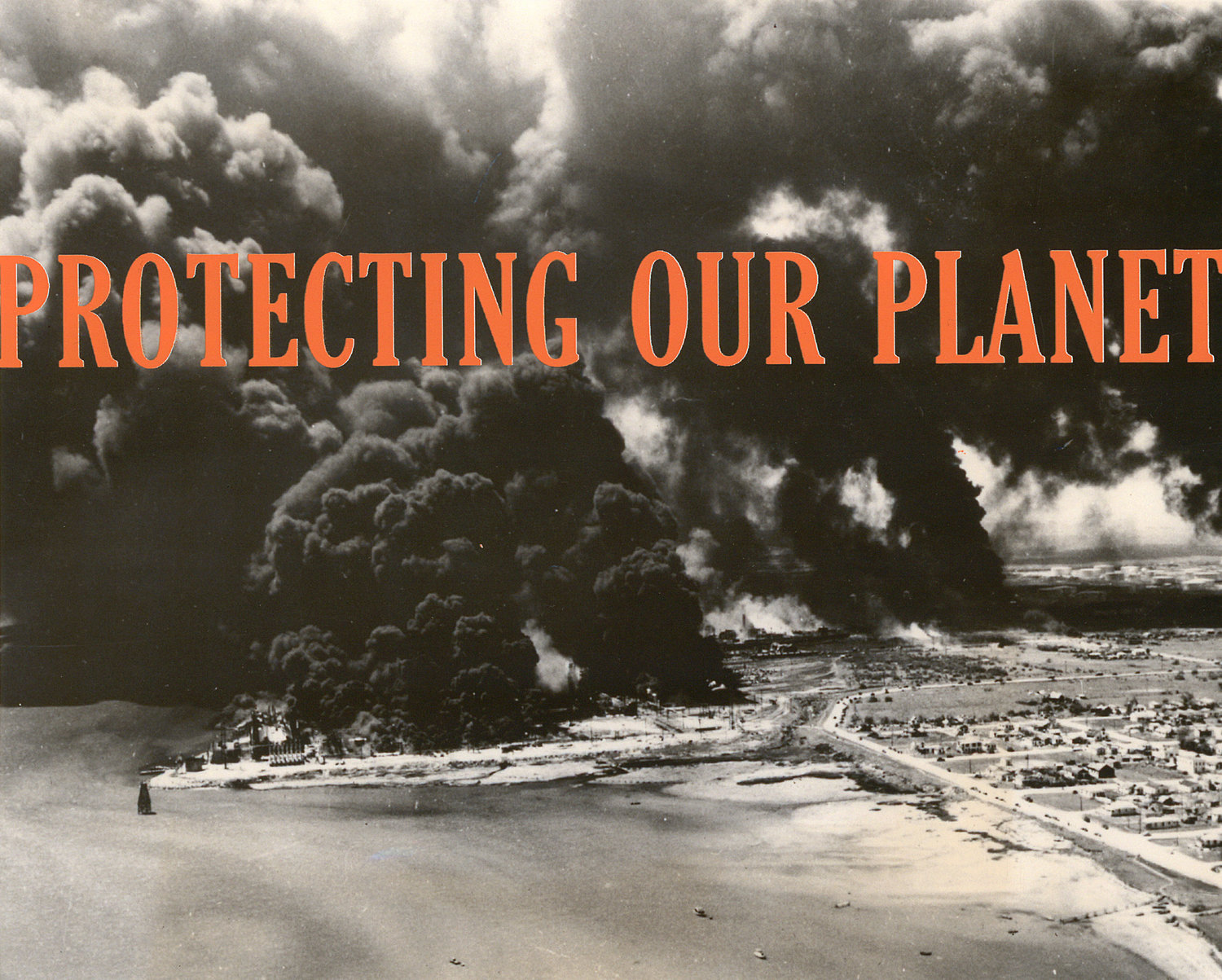

Kirsten Stolle, Protecting Our Planet (from the series By The Ton), 2016. Silkscreen on archival pigment print

Any other upcoming work, field of research and concerns, or events you are currently working on?

I am currently working on two projects:

By The Ton is an archival photo/silkscreen/collage series investigating the historical legacy of multinational chemical companies and their influence on the global food system. This series dissects the prevailing rhetoric and critiques the practice of corporate greenwashing.

Disarm is a collage and drawing project examining the visual and psychological impact of former US Nike missile sites. I began Disarm at the end of 2015 as a way to investigate military propaganda within a 21st century framework. Given the incoming US political administration and in context with our current state of expanded drone warfare, increased surveillance systems and the uncertain relationship with Russia, my Disarm artistic research is taking on greater and urgent importance.

Thanks Kirsten!

Kirsten Stolle’s solo exhibition Proceed at Your Own Risk is at NOME in Berlin until 8 April 2017

Stolle also participates to Evidentiary Realism, a group show presented by NOME Gallery + Fridman Gallery. It opens at the Fridman Gallery on 28 February in New York City and runs until 31 March, 2017.