In 1993, a management professor and sociologist called Peter Drucker published Post-Capitalist Society. The book predicted that the impact of information technology on the labour market would be so great that it would ultimately lead to the fall of capitalism by 2020. His prediction didn’t come true but he was right when, writing at a time when the internet was still in its infancy, he anticipated that knowledge, rather than capital, labour or land ownership, would one day become the basis for wealth. He called “post-capitalist society” the world that would emerge as a consequence of this shift.

Roger Hiorns, The retrospective view of the pathway, 2017-ongoing. © Photo : Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

View of the exhibition Post-Capital: Art and the Economics of the Digital Age, 02.10.2021 — 16.01.2022, Mudam Luxembourg. © Photo: Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

The exhibition Post-Capital. Art and the Economics of the Digital Age at MUDAM in Luxembourg draws on Drucker’s insight to address the inherent paradox within a capitalist system that is both dependent upon technological progress and menaced by it.

As the show demonstrates, digital technology has left (almost) no aspect of human experience untouched: our data have been commodified, our individual sovereignty challenged, our labour monitored and “gamified”, our attention monetized, our consumption turbo-charged, etc. Even our language had to adapt to the speed and small size of smartphones.

The artworks selected for the Post-Capital show explore the aesthetics, paradoxes, absurdities and ethical questions posed by the economics of technologies we all criticise but find ourselves unable to ban from our lives.

Quick overview of some of the works I particularly enjoyed during my visit:

Cao Fei, Asia One, 2018

Cao Fei, Asia One, 2018

Cao Fei, Asia One (trailer), 2018

Cao Fei’s Asia One made it worth the time spent on the suuuuuuper slow train to Luxembourg Ville. The film was shot inside a gigantic automated warehouse inhabited by robots, conveyor belts and only 2 human employees. At first, they mostly ignore each other to focus on the constantly flowing stock and alienating atmosphere. Soon the film changes tempo: the protagonists stop being hypnotised by the rhythm of the sorting facility, they finally notice each other and express a kind of rebellion against the cold efficiency and frigidity of their surroundings. The scenes are interspersed with choreographies in which workers, dressed to evoke the Cultural Revolution–era, dance around the never-stopping machines and give life to the grey space. Asia One should feel futuristic. It is painfully and poetically contemporary.

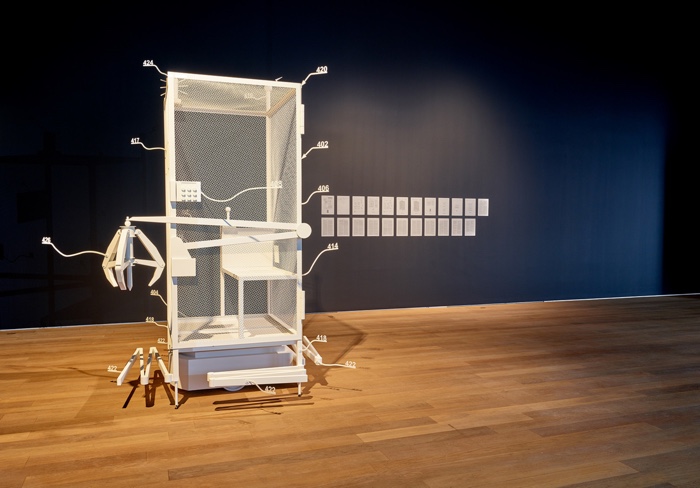

Simon Denny, Amazon worker cage patent drawing as virtual Aquatic Warbler cage, 2020. View of the exhibition Post-Capital: Art and the Economics of the Digital Age, 02.10.2021 — 16.01.2022, Mudam Luxembourg. © Photo: Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

In 2016, Amazon filed a patent for a device described as a “system and method for transporting personnel within an active workplace”. It looked essentially like a cage large enough to fit a worker.

Simon Denny followed the sketches in the patent and turned them into a sculpture that painfully materialises the horrors of the ever-shifting hierarchy between humans and machines in a data-fuelled economy. In this vision, the robots are not “stealing our jobs”, they use humans as biological extensions of algorithms.

The cage is exhibited alongside excerpts from the patent and a pair of “document-reliefs” made using a 3D printer to render shapes from the cage in cut and layered paper copies of the document. Visitors are invited to scan a QR code, download an app and view the endangered Aquatic Warbler bird trapped inside the cage. The AR component alludes to an ongoing ecological disaster caused by the invisible extractivist and energy-intensive dimensions of digital technology.

Hito Steyerl, FreePlots, 2019-ongoing. © Photo : Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

Hito Steyerl, FreePlots, 2019-ongoing. © Photo : Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

The inspiration for FreePlots came from Hito Steyerl’s discovery that an artwork she had sold was stored in the Geneva Freeport, a duty-free warehouse that enables super-rich clients to avoid paying taxes on luxury goods like art pieces. In order to redress the economic imbalance caused by the presence of her work in a free port, Steyerl invested the money she made from the sale in manure for a community garden in Berlin. After this first foray into communal land use, Freeplots became a traveling project. The artist installs free port-shaped wooden planters in different locations, collaborating each time with local community gardens. Excerpts of the artist’s interview with the gardeners are stenciled on the crates and relayed as a recording forming the soundtrack to the installation.

FreePlots can be seen as a model to counter capitalist frameworks by highlighting alternatives to private ownership. For the artist, community gardens (often maintained by women and migrant communities) are also an important symbol of opposition to nationalism and xenophobia.

Oliver Laric, Hermanubis, 2021. © Photo : Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

Oliver Laric, Ram with Human, 2020. © Photo : Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

Oliver Laric, Reclining Pan, 2021. © Photo : Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

Oliver Laric selected four sculptures from his public catalogue of 3D models of antiquities. Each of them explores relationships between humans and other animals. Hermanubis is a copy of a c. 100 CE sculpture that combines the Greek god Hermes with the canine Egyptian deity Anubis. The half-man and half-goat Greek God Reclining Pan is the copy of a 16th-century sculpture which, in turn, was sculpted from the remnants of a Roman relief.

While the majority of the 3D scans are made with the consent of the museums that own the original works, others employ a technique called photogrammetry (producing a 3D model from hundreds of photographs) as a legal workaround.

By replicating the artworks using 3D technology, Laric is complicating our perception of the past and the present. By making the files available for download, artworks that you would normally need to pay a museum entrance fee to enjoy become accessible to a different audience of individuals who can directly engage with the work.

Sondra Perry, IT’S IN THE GAME ‘18, 2018. © Photo : Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

Sondra Perry‘s installation is inspired by a personal story: the physical likeness and biometric data of her twin brother and college basketball player Sandy Perry were used to create a videogame avatar for which neither he nor the other athletes featured in the game were consulted or paid. Perry’s installation pairs this real-life story with views of African artefacts held in institutions like the Metropolitan Museum of Art and The British Museum. Perry’s juxtaposition between personal experience and museum collections unravels a long history of appropriation of the imagery and cultural heritage of Black people in historical painting, news media and social media.

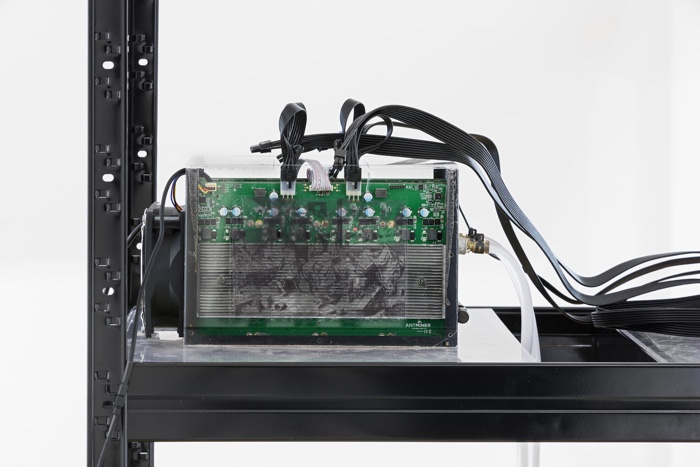

Yuri Pattison, the ideal (v/0.3.2), 2015-ongoing

Yuri Pattison, the ideal (v/0.3.2), 2015-ongoing

Yuri Pattison’s the ideal (v/0.3.2) explores the ecological impact of the industrial practice of Bitcoin mining in China. The installation was made in collaboration with Eric Mu, the former Chief Marketing Officer of a Beijing-based startup involved in crypto-mining. Mu filmed a Bitcoin mine located in a remote location on the edge of the Tibetan Plateau in Sichuan, China. The video mixes scenes of warehouses full of Bitcoin mining rigs and the neighbouring hydroelectric dam with views of the surrounding area.

Although Bitcoin is a digital currency, the mining process itself is very energy-intensive. In order to save on energy costs, many companies have to move their operations to places where hydroelectric power is cheap and plentiful. The video plays alongside an active water-cooled Bitcoin mining machine. Both the video and the machine are contained within industrial racking that resembles the shelving used in Bitcoin warehouses. The title of the work refers to Ideal Money, a theoretical notion put forward by mathematician John Nash to stabilise international currencies.

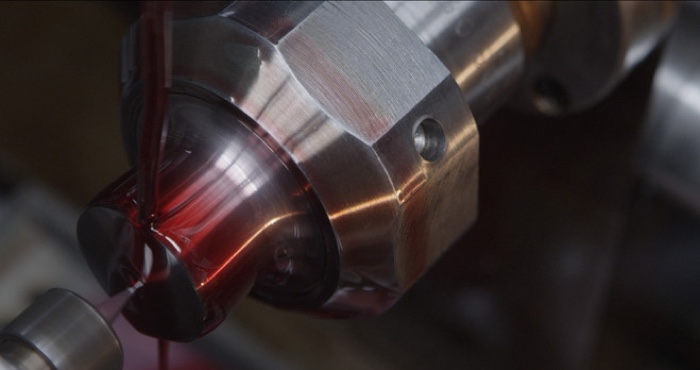

Mohamed Bourouissa, All-in (film still), 2012

Mohamed Bourouissa, All-in (film still), 2012

Mohamed Bourouissa‘s All-in video was filmed in the Pessac factory in Paris where euro coins are minted. Edited in the style of a music video, All-In retraces the process of minting a medallion featuring the profile of French rapper Booba. The video is set to the beats of Foetus which chronicles the musician’s rise from early childhood to drug dealing to the successful rap entrepreneur he is today. The video refers to what Mohamed Bourouissa calls the ‘liberal anarchism’ of western societies, where individual success is measured by money.

Nick Relph (via)

Nick Relph scanning the . Image via @ preechopress / Instagram (via)

Nick Relph has made hundreds of scans of computer-generated architectural drawings which are often printed at a large scale and wrapped around New York construction sites to illustrate the designs of the buildings being erected. The artist makes a copy of the rendering posters using a hand-held scanner. He then stitches the digital images together and develops them in analog format. The symbols of rampant gentrification loose their glamour and prestige in the process. Fragments are missing, layers of dirt and graffiti reveal the visual and social misery that most of these constructions often generate.

More images from the exhibition:

Roger Hiorns, The retrospective view of the pathway, 2017-ongoing. © Photo : Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

Nora Turato, eeeexactlyyy my point., 2021. © Photo : Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

View of the exhibition Post-Capital: Art and the Economics of the Digital Age, 02.10.2021 — 16.01.2022, Mudam Luxembourg. © Photo: Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

View of the exhibition Post-Capital: Art and the Economics of the Digital Age, 02.10.2021 — 16.01.2022, Mudam Luxembourg. © Photo: Rémi Villaggi | Mudam Luxembourg

Post-Capital. Art and the Economics of the Digital Age was curated by Michelle Cotton. The exhibition remains open until 16 Jan 2022 at MUDAM in Luxembourg.