Liberty Crossing is a complex for 1,700 federal workers and 1,200 contractors. Photo by Michael S. Williamson / The Washington Post

Liberty Crossing is a complex for 1,700 federal workers and 1,200 contractors. Photo by Michael S. Williamson / The Washington Post

Previously: Politics and Practices of Secrecy (part 1).

And this is part 2 of the notes i took during the Politics and Practices of Secrecy symposium which took place at King’s College in London last month. My reports do not follow the schedule of the panels, nor do they cover all the talks. I’m just cherry picking the more interesting moments of the day. Part 1 focused on the art projects. This post is less uniform in its theme. Two of the presentations i enjoyed covered the representation of intelligence agencies in films and tv fiction. Another was about the influence that new forms of surveillance are having on the rise of home-grown (‘home’ being the U.S.A., the symposium was organised by the Institute of North American Studies) white extremist groups. And a fourth talk wondered if transparency could fix our democracy.

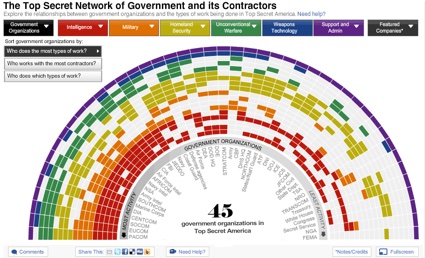

The Top Secret Network of Government and its Contractors

The Top Secret Network of Government and its Contractors

Let’s start with Timothy Melley, Professor Affiliate of American Studies at Miami University and author of The Covert Sphere. Secrecy, Fiction, and the National Security State and of Empire of Conspiracy. The Culture of Paranoia in Postwar America.

In his talk, ‘The Democratic Security State: Operating Between Secrecy and Publicity’, Melley listed up a few numbers:

This secret world costs 8 billion dollars per year.

According to 2010 Washington Post analysis:

50,000 intelligence reports are written each year. Their volume is so large that most are never read.

The intelligence hides out in the open:

In Washington D.C., 33 building complexes for top-secret intelligence work have been built (or are being built) since September 2001. Their total surface is equal to 22 U.S. Capitols.

Similar buildings can be found in 10,000 other locations across the U.S.A.

The complexity of this system defies description Lt Gen. (Ret.) John R. Vines

The U.S. covert state is a growing industry. It handles a huge number of secrets all over the country. It relies on democratic structures but acts like a shadow state that has its own territory and laws. It also support some film makers by lending helicopters needed for films that publicize the covert world. The reason for that is that the secret programme needs public approval.

What we know about the CIA comes from leaks but also from fiction. Our screens are awash with what Melley calls ‘terror melodrama.” One of his presentations slides even listed those films. Covert CIA operations are celebrated in books, films, games, tv series, etc. Earlier this year, the CIA, pleased with the way it is portrayed in “Homeland”, invited the show’s cast and producers to visit its headquarters in Virginia and have a discussion. Another example is when Michelle Obama presented the 2013 Best Picture award to Ben Affleck’s Argo, a film adapted from CIA operative Tony Mendez’s book The Master of Disguise and the 2007 Wired article The Great Escape: How the CIA Used a Fake Sci-Fi Flick to Rescue Americans from Tehran.

An exit marker points to the National Security Agency. Photo by Michael S. Williamson / The Washington Post

An exit marker points to the National Security Agency. Photo by Michael S. Williamson / The Washington Post

The N.S.A. properties in Maryland total 8.6 million square feet of office space, 1.3 times as big as the Pentagon. Photo by Sandra McConnell, N.S.A.

The N.S.A. properties in Maryland total 8.6 million square feet of office space, 1.3 times as big as the Pentagon. Photo by Sandra McConnell, N.S.A.

Keeping with the spy in entertainment theme, Matt Potolsky, Professor of English at University of Utah, looked at the representation of the NSA on tv and in cinema.

Fiction and films are often the only way the public can picture and judge for themselves the activities of intelligence agencies. FBI, KGB, CIA have often been presented in films. How about the NSA? According to Potolsky, the NSA never turned into real fictional tropes.

The 2009 movie Echelon Conspiracy features NSA agents and the signals intelligence collection system Echelon.

There have been more recent attempts to depict the activity of the massive NSA:

– Citizenfour by Laura Poitras, of course.

– but also “Let Go, Let Gov” a South Park episode that satirizes the 2013 mass surveillance revelations, and casts Eric Cartman in the role of a whistleblower, in which he infiltrates the NSA in protest of the agency’s surveillance of American citizens. In the episode, NSA agents appear as little more than anonymous cogs working behind desks. This obviously is very different from the ‘Men in Black’ style description of CIA agents. The NSA agents look like they are working for a multinational corporation rather than for a spy agency.

South Park, Let Go Let Gov

Mark Fenster, Professor at the Levin College of Law (University of Florida) and author of the book Conspiracy Theories: Secrecy and Power in American Culture. His talk was titled ‘Secrecy and the Hypothetical State Archive.’

Fenster started by reminding us of a whistleblower of the early 1970s. Daniel Ellsberg was employed by the RAND Corporation when he not only read classified documents he wasn’t supposed to open but also photocopied and released them to The New York Times and other newspapers. The Pentagon Papers, officially titled United States – Vietnam Relations, 1945-1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense, were top-secret documents that charted the US’ political-military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967.

In June 1971 the New York Times began publishing the Pentagon Papers (image)

In June 1971 the New York Times began publishing the Pentagon Papers (image)

There is now a trust in ‘transparency’ but, Fenster asks, Can transparency fix our democracy? Obama was elected to end Bush’s secrecy. But the secrecy is now as deep as ever. If not deeper.

But Fenster says, information leaks. Sometimes from the top, sometimes from the bottom. Sometimes drop by drop, sometimes it flows.

It is particularly tricky to control State information. If you think about the model of communication Sender-Message-Receiver, the Sender would be the State, the Message is state information and the Receiver is the public.

The state is organizationally complex, it is spatially deployed, it is enclosed in buildings, offices. In truth, it is a mess that is difficult to keep shut.

State information is difficult to perceive clearly, it is a vast amount of information, it is hard to archive and to control its release. Sometimes state information can leak by mistake.

The public is made of individuals and they will have their own interpretation of any information released.

In brief, information cannot be controlled, on any level.

According to Fenster, the revelation of a secret often offers marginal gains. It certainly doesn’t lead necessarily to a reformed democracy.

Another talk i found very informative was the one by Hugh Urban, professor of religious studies at Ohio State University and author of The Church of Scientology: A History of a New Religion

His talk, ‘The Silent Brotherhood: Secrecy, Violence, and Surveillance from the Brüder Schweigen to the War on Terror’ looked at the white males’ belief that they are the victims of racial oppression. In their view, white males are persecuted by women, Black people, Muslims, Jews, etc. That’s what Urban calls the “white man falling” syndrome.

Brüder Schweigen or Silent Brotherhood, was a white nationalist revolutionary organization active in the United States between September 1983 and December 1984. Its founder Robert Jay Mathews wanted to create an elite vanguard of Aryan warriors to save the white race. The Silent Brotherhood group was responsible for a number of violent crimes: robberies, bombings, murders, counterfeiting operations, etc.

Brüder Schweigen or Silent Brotherhood, was a white nationalist revolutionary organization active in the United States between September 1983 and December 1984. Its founder Robert Jay Mathews wanted to create an elite vanguard of Aryan warriors to save the white race. The Silent Brotherhood group was responsible for a number of violent crimes: robberies, bombings, murders, counterfeiting operations, etc.

Nowadays, much of the anti-terrorist attention focuses on radical Islam, neglecting home-grown white extremist groups. Figures show that the number of patriot groups in the U.S. is growing very rapidly. The reasons for that are many: bad economic conditions, black president but also the rise of surveillance which augments these people’s distrust of the FBI, NSA and other governmental agents.

Urban’s conclusions were that:

1. Secrecy is both the explanation and the radical solution for the ‘white man falling’ syndrome.

2. New forms of surveillance play into, feed and reinforce the narratives of such radical groups.

Politics and Practices of Secrecy was organized by the Institute of North American Studies at King’s College London, on 14-15 May, 2015.