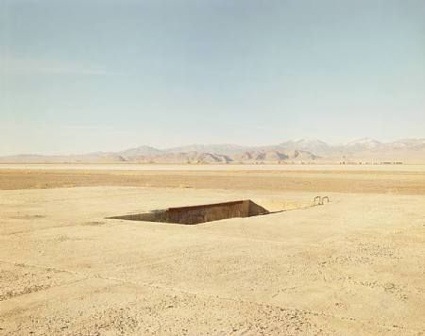

Richard Misrach, Atomic Bomb Loading Pit, Wendover Air Force Base, Utah, 1989

Richard Misrach, Atomic Bomb Loading Pit, Wendover Air Force Base, Utah, 1989

Trevor Paglen, Headquarters of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency in Springfield, Virginia

Trevor Paglen, Headquarters of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency in Springfield, Virginia

I’ve been strangely busy (‘strangely’ because believe me it’s not my style at all to be a busy person) over the past couple of weeks and i never got a chance to sit down and write a small report of the Politics and Practices of Secrecy symposium which took place at King’s College in London last month. Here’s the blurb that lured me into spending a whole day in a lecture hall:

In the wake of the Snowden revelations about the surveillance capabilities of intelligence agencies, this interdisciplinary symposium gathers experts to discuss the place and implications of secrecy in contemporary culture and politics.

The event started with a keynote by Jamie Bartlett about the Secrets of the Dark Net. It was entertaining and more about the dark sides of the internet in general than strictly speaking about the Silk Road. The journalist talked us through his adventures online and offline with sex cam ladies, neo-nazis, drug sellers and anorexic girls. If you’re curious about the content of the talk, then i advise you to check out his book The Dark Net.

The event started with a keynote by Jamie Bartlett about the Secrets of the Dark Net. It was entertaining and more about the dark sides of the internet in general than strictly speaking about the Silk Road. The journalist talked us through his adventures online and offline with sex cam ladies, neo-nazis, drug sellers and anorexic girls. If you’re curious about the content of the talk, then i advise you to check out his book The Dark Net.

The symposium itself looked at how the relationships between citizens and government have changed since the Snowden revelation, the impact of secrecy on society and the place of the subject in a world that keeps us under close surveillance and doesn’t regard us as fully-formed political agents. The angle was very much American. Not because the USA is the only nation that uses and abuses of secrecy (although they are making a name for themselves in that field) but because the symposium was organized by the Institute of North American Studies at King’s College.

I won’t cover all the symposium presentations. I’m just going to do a pick and mix of what i heard there. This first post about the event might still be fairly coherent though because it will focus on the arty Roundtable 2: Aesthetics of the Secret. And since he is an artist and an artist who has some valuable ideas to share about secrecy, discrimination and control, i’m also adding to this post Zach Blas’ talk (which was part of another series of talks that zoomed in on Opacity and Openness.)

Zach Blas, Facial Weaponization for Queer Opacity at LA Pride, reclaim:pride / ONE Archives

Zach Blas, Facial Weaponization for Queer Opacity at LA Pride, reclaim:pride / ONE Archives

Let’s start with Zach Blas. He is an artist, writer and Assistant Professor in the Department of Art at the University at Buffalo. The title of his talk ‘Informatic Opacity‘ is also the one of his upcoming book.

The idea of informatic opacity is explored in two of Blas’ artworks. The first one, Facial Weaponization Suite, is a series of workshops in U.S. and Mexico that looked at biometric facial recognition. The artist worked with members of specific minority communities (queers, black people, etc.) to create masks that are modeled from the aggregated facial data of participants. The amorphous and slightly sinister masks are then worn in public performances. The masks represent each individual but cannot be detected as human faces by biometric facial recognition technologies. The work is a dark critique of the silent and gradual rise of the use of biometric facial recognition software by governments to monitor citizens. The symbol of the mask is also important. Pussy Riot, members of the Black Bloc and the Zapatistas wear masks to hide their face but also because masks make them visible.

For Blas, the main motivation behind the work wasn’t so much privacy and transparency. His first interest laid in highlighting a technology that standardizes identity globally in order to create templates that can calculate identity and can be applied around the world.

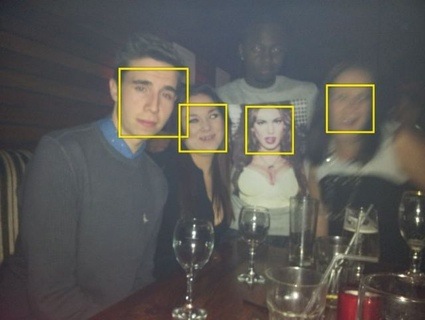

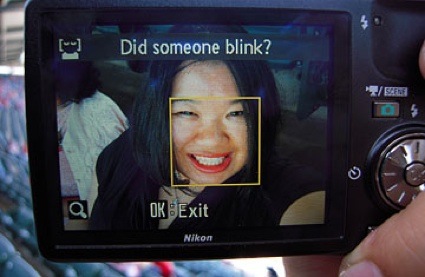

The standards of face recognition technology are rigid and they can break down. As the two examples below demonstrates, these technologies are routinely accused of not recognizing non-Caucasian faces:

‘When camera facial recognition fails’ (via)

‘When camera facial recognition fails’ (via)

Are Face-Detection Cameras Racist? (via)

Are Face-Detection Cameras Racist? (via)

Not being recognized by biometric machines makes some people more vulnerable to discrimination and criminalization.

Édouard Glissant called for the right to opacity. For him opacity was protecting anyone who is ‘diverse’. Blas book takes Glissant’s idea of opacity and puts it into the context of informatics. Information opacity, he says, resists forms of globalization and standardization.

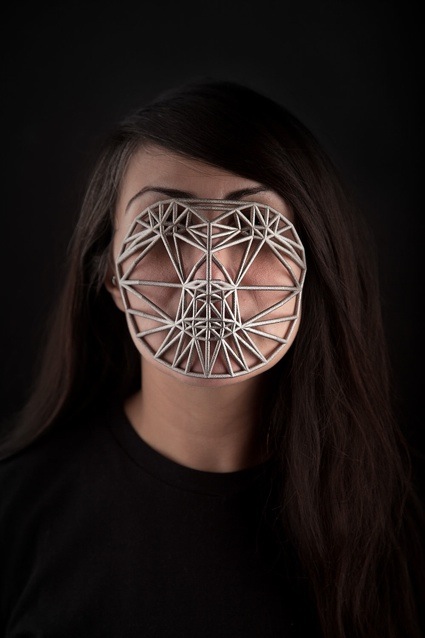

Zach Blas, Face Cage #2, portrait

Zach Blas, Face Cage #2, portrait

The second work Blas mentioned is his Face Cages series which focuses on biometrics as a form of capture.

Face Cages is a dramatization of the abstract violence of the biometric diagram. Diagrams are fabricated as three-dimensional metal objects, evoking a material resonance with handcuffs, prison bars, and torture devices used during slavery in the US and the Medieval period. The virtual biometric diagram, a supposedly perfect measuring and accounting of the face, once materialized as a physical object, transforms into a cage that does not easily fit the human head, that is extremely painful to wear. These cages exaggerate and perform the irreconcilability of the standardized, neoliberal biometric diagram with the materiality of the human face itself-and the violence that occurs when the two are forced to coincide.

Now to Roundtable 2, Aesthetics of the Secret which was, unsurprisingly, the one i was most looking forward to listen to.

John Beck, Director of the Institute for Modern and Contemporary Culture at the University of Westminster, kicked of the session with ‘Photography’s Open Secret.’

The talk explored the desert landscape in the South West of the U.S., one of the most photographed regions in the world, but also one that hosts a vast amount of secrecy.

The desert is a space where there is nothing and where therefore anything can be done and left: military bases, weapon testing facilities, nuclear waste, etc. It can be used as a dump space where unnecessary leftovers of power can be placed. It is a space where secrets are literally left into the open.

The medium of photography echoes the ambiguous characteristic of the desert. Photography is an instrument for revealing, unveiling, documenting and exposing. But it can also be used to hide, by leaving things out of the frame, by staging or doctoring evidence. Photography is at once a medium of transparency and a medium of opacity. And that makes it difficult to regard photography as a source of reliable evidence.

Richard Misrach, Bomb Crater, Wendover Air Force Base, Utah, 1989

Richard Misrach, Bomb Crater, Wendover Air Force Base, Utah, 1989

Richard Misrach photographed places that are now less restricted than they were during the Cold War but that were used to conduct secret programs and operations.

Trevor Paglen, Chemical and Biological Weapons Proving Ground / Dugway, UT; Distance ~ 42 miles; 10:51 a.m., 2006

Trevor Paglen, Chemical and Biological Weapons Proving Ground / Dugway, UT; Distance ~ 42 miles; 10:51 a.m., 2006

After 9/11, Trevor Paglen has taken up the role of photographer/investigator of sites of secrecy. Using limit telephotography, he documents black sites and other secret spaces and programs of the USA. Some of his photos, however, move toward abstractions and as such, embody the skepticism that photography can provide us with straightforward representations of the world.

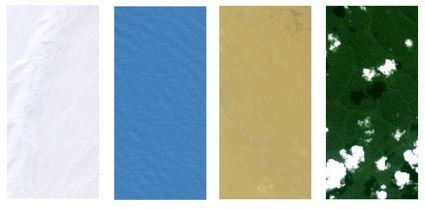

Laura Kurgan, Monochrome Landscapes, 2004

Laura Kurgan, Monochrome Landscapes, 2004

Laura Kurgan bought hi-res satellite images showing four vulnerable landscapes: a desert in Iraq, the rain forest in Cameroon, the tundra in Alaska, and the Atlantic Ocean. Seen from afar, the images evoke monochromatic Minimalism, but a closer investigation reveal traces of geopolitical issues such as illegal logging or helicopters flying over the desert during “Operation Iraqi Freedom.”

Mishka Henner, Staphorst Ammunition Depot, Dutch Landscapes

Mishka Henner, Staphorst Ammunition Depot, Dutch Landscapes

Mishka Henner, Paleis Noordeinde, Den Haag, Dutch Landscapes

Mishka Henner, Paleis Noordeinde, Den Haag, Dutch Landscapes

When Google launched its satellite imagery service in 2005, some governments attempted to censor sites deemed vital to national security. The Netherlands, for example, hid hundreds of significant sites including royal palaces, fuel depots and army barracks behind stylist multi-coloured polygons. Ironically, it made the censored sites even more conspicuous. The country has since adopted a less distinctive method of visual censorship.

The second speaker of the roundtable was Neal White, artist, Associate Professor in Art and Media Practice at Bournemouth University, he is also Director of Emerge – Experimental Media Research Group.

His talk, Secrecy and Art in Practice, looked at the various methods art employs to reflect on the practice of secrecy.

Taryn Simon, The Central Intelligence Agency, Art CIA Original Headquarters Building, 2003/2007

Taryn Simon, The Central Intelligence Agency, Art CIA Original Headquarters Building, 2003/2007

He mentioned the Critical Art Ensemble’s tactical biopolitic works, Taryn Simon’s photo series An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar, Trevor Paglen (but then almost every single speaker spoke about Paglen’s work), Charles Stankievech‘s Counterintelligence, etc.

White also talked briefly about the works he is involved in with the Office of Experiments. I’ve blogged in the past about The Overt Research Projects which combine field observation, alternative knowledge gathering and experimental geography techniques with other research methods to archive and geo-map spaces related to techno-scientific and industrial /military research in the UK.

The Mike Kenner Archive

The Mike Kenner Archive

I was also surprised to learn about The Mike Kenner Archive which was donated to the Office of Experiments in 2009 so that they can show the archived material to the public. Mike Kenner‘s collection of thousands of documents were obtained following over thirty years of research and FOI (Freedom of Information) requests into the activities at the Biochemical Research Centre at Porton Down, Wiltshire (referred to as MRE) and other sensitive research establishments. The documentation contains photographs, de-classified but restricted secret and top-secret documents, cabinet office and official correspondence, experimental data, images, diagrams , analysis, video, photographs, newspaper cuttings etc. Many of these highlight experiments that had a significant impact in the region of Weymouth in the UK, with experiment conducted on the public using live pathogens, largely through around Lyme Bay. Far from being historic research alone, Kenner’s work points to controversy generated by what may well be ongoing scientific trials and experiments, continuing to this day often concealed from the public in plain sight.

The last speaker of the roundtable wasn’t an artist but a Senior Lecturer at King’s College and the curator of the whole event. Clare Birchall explored how artists are using the materiality of secrecy in their practice. Unsurprisingly, she discussed Paglen and mentioned his keynote at last year’s edition of Transmediale. Which i’m copy/pasting below:

Trevor Paglen — transmediale 2014 keynote: Art as Evidence

Birchall also spoke in details about Jill Magid‘s work at the AIVD, the Dutch secret service.

In 2005, AIVD asked her to create a work for its new headquarters. They were hoping that the commission would help improve its public persona by providing “‘the AIVD with a human face.”

Magid spent the following three years meeting with eighteen employees of AIVD in “non-descript public places.” AIVD restricted the artist from using recording equipment, so she had to write down her notes. She never disclosed the identity of her contact but compiled the information she had collected during the interviews into a collective persona that she referred to as “The Organization.”

Jill Magid’s artwork being confiscated from Tate Modern Monday, January 4, 2010. Photo: ©Amy Dickson (via)

Jill Magid’s artwork being confiscated from Tate Modern Monday, January 4, 2010. Photo: ©Amy Dickson (via)

When AIVD agents visited the first exhibition of the project in 2008, they confiscated several works and censored the draft of Magid’s report.

The artist “protested against the censorship of her own memories,” prompting AIVD to suggest that she “‘present the manuscript as a visual work of art in a one-time-only exhibition, after which it would become the property of the Dutch government and not be published.'” Magid’s 2009/10 exhibition at Tate Modern, Authority to Remove, marked the fulfillment of this request: the uncensored report sat securely behind glass. In its penultimate state, the project thus expressed “what it means to have a secret but not the autonomy to share it.” (via)