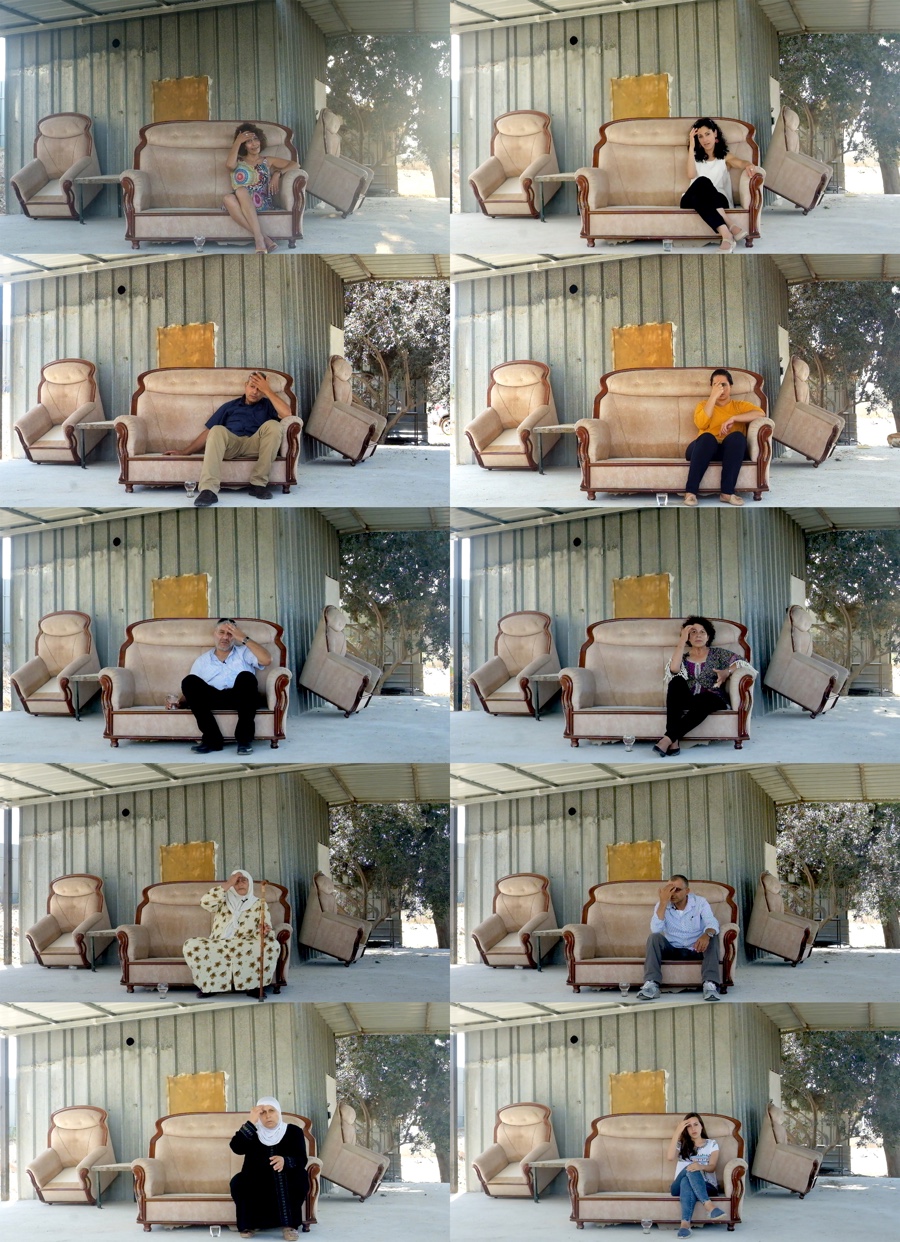

Noor Abed, The Air Was Too Thin to Return the Gaze, 2016. Video stills. Image courtesy of the artist

The collaborative contemporary art biennial Qalandiya International is opening this month across towns and villages in Palestine. It will be looking for new perspectives around the Return, a theme at the root of many Palestinian dreams, literature and artworks following the Nakba (the exodus of more than 750,000 Palestinians who either fled or were expelled from their land when the Israeli state was established in 1948.)

The general title of this edition of QI is This Sea is Mine and i can’t help but think that it must have a bitter-sweet resonance for the crew of the Women’s Boat to Gaza, a group of women who set sail from Barcelona in an attempt to peacefully break the Gaza blockade, and who were intercepted and arrested by the Israeli navy a few days ago.

QI exhibitions and events are taking place in Haifa, Beirut, Gaza, Jerusalem, Bethleem, Amman and even London but the one that caught my attention is opening tomorrow in Ramallah: Pattern Recognition gathers works from the nine Palestinian artists shortlisted for the 2016 edition of the Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA 2016).

The projects in the exhibition explore how strategies of repetition open up avenues for critically rethinking issues of time, place, memory and authenticity. Straddling the grey zones between fact and fiction, original and copy, ruin and repair, the works re-imagine the mechanics of representation in the context of Palestine, where geographies, histories and identities are fragmented.

The newly commissioned works investigate this theme of repetition through works as diverse as an improvised performance based on the sounds of war, the exploration of the traces left by an UFO spotted over the village of Bir-Nabala, a patchwork blanket that is knitted and then unravelled in echo of the Palestinian-Syrian refugees who have to rebuild their life with each displacement, the reviving of an archival photo of a 1970s Palestinian female fighter through various moments in the history of post-Nakba Palestinian art, etc. There is a lot of drama, dream, despair and emotions in these artworks but there’s also a high dose of that unflappable, that very dark and subtle Palestinian humour.

Inas Halabi, ‘Mnemosyne’, 2016. Video still. Photo courtesy of the artist

Unfortunately, I can’t make it to Ramallah to see the show but i did manage to catch up with curator and critic Nat Muller while she was setting up the exhibition:

Hi Nat! You’ve curated the 9th edition of the Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA 2016). I think the competition takes place every two year. Looking back at previous editions, do you see some constant concerns or evolution in the themes explored by the artists or the way they engage with them?

Many Palestinian artists, regardless of their place of residence or age, address issues that define the Palestinian plight and the reality of living under the Israeli occupation. These range from forced exile, dispossession, violence, and curbs in mobility, to the construction of memory (be that individual or collective), historiography, (national) identity, and the relationship to the land and territory. The Young Artist of the Year Award has been around for 16 years and while on the one hand much has happened (a second intifada, a separation wall, Israel’s disengagement from Gaza, and three Gaza wars), there is unfortunately more that has not happened. Palestinians still do not have a sovereign state. On a daily basis Palestinian experience this state of suspension, of being stuck between the desire for a nation and the harsh reality of living under occupation. So this post-Oslo inertia is also a theme that echoed in artists’ work.

Abdallah Awwad, The Horizon’s Pathway, 2016. Sculptures made from iron, wires, gypsum, fabric, silicon. Image courtesy of the artist

For example, for Pattern Recognition Abdallah Awwad produced sculptures in which it is unclear whether they are in the process of becoming, or of coming apart, very much akin to the Palestinian condition.

Somar Sallam’s video and wool. Photo: Nat Muller

Somar Salam, ‘Disillusioned Construction’, 2016. Video stills. Image courtesy of the artist

Somar Salam, ‘Disillusioned Construction’, 2016. Video stills. Image courtesy of the artist

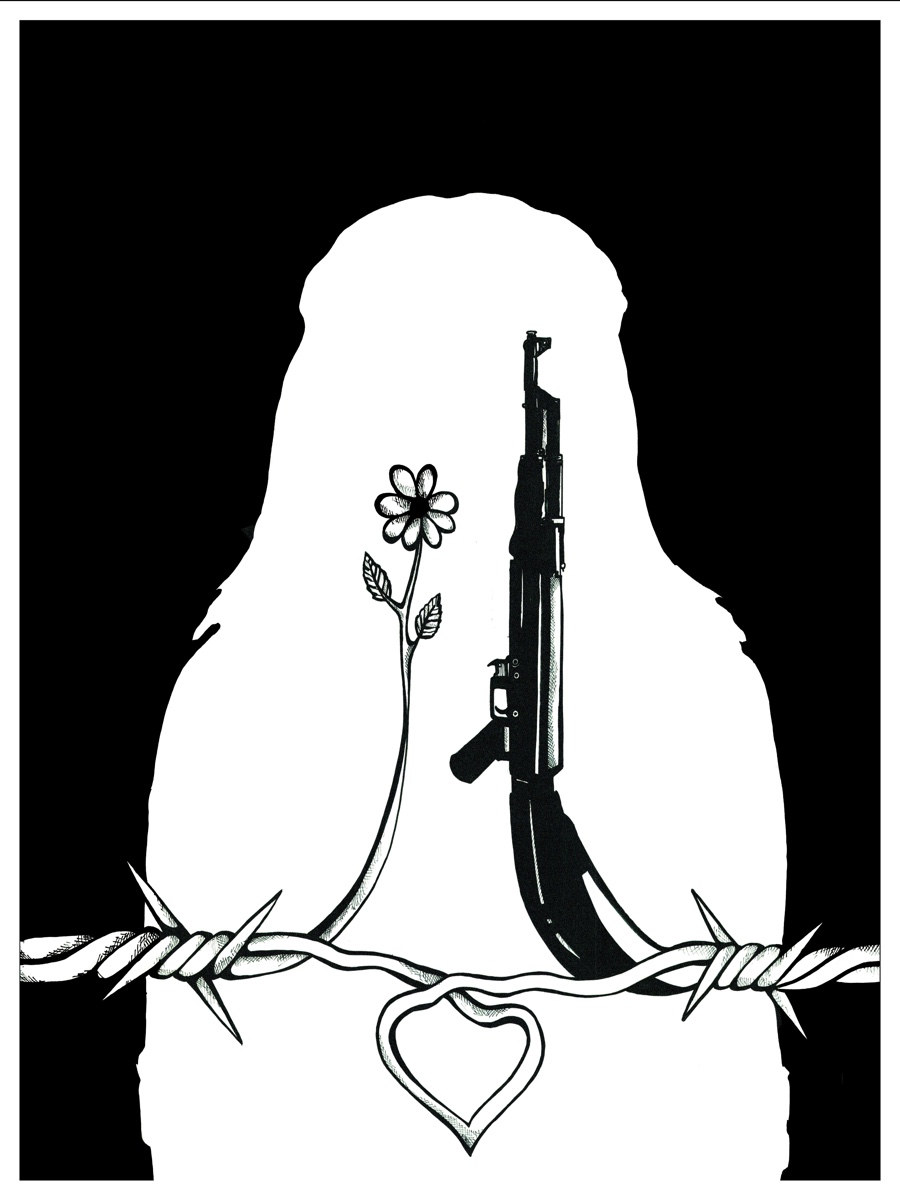

Somar Sallam’s video shows a woollen cover that is crocheted and then unravelled over and over again. But all this being said, I’ve seen artists engage more with Palestinian art history, for example in her project for the show Majd Masri takes an iconic photo of a female fedayee and redoes them in six specific styles corresponding to Palestinian art history and political events.

More generally, over the past decade ‘humour’ has become an adequate critical and artistic strategy to point out the dramatic, but surrealist, aspects of Palestinian life. I warmly recommend readers to check out Chrisoula Lionis’s brilliant book Laughter in Occupied Palestine: Comedy and Identity in Art and Film.

Majd Masri, Haphazard Synchronizations, 2016. Acrylic on canvas, prints, collage. Image courtesy of the artist

Majd Masri, Haphazard Synchronizations, 2016. Acrylic on canvas, prints, collage. Image courtesy of the artist

The artworks explore strategies of repetition. Why are they so important in the Palestinian context?

The exhibition takes place within the context of Qalandiya International, the Palestinian biennial. It is organised for the third time now, and its main theme is ‘return’, which is a complex notion for Palestinians, but strongly resonates now with the global refugee crisis. I was tasked to formulate a response to the theme of ‘return’ and was interested in seeing what kind of concepts young artists would come up with if they would consider the politics of form (repetition, pattern, rhythm), rather than drawing on a more familiar conceptual and visual lexicon of nostalgia and traditional iconography (keys, oranges, olive groves). In other words, how would they re-imagine the mechanics of representation in the context of Palestine where geographies, histories and identities are so fragmented and have been represented in very particular ways, from broadcast media to literature and art. Repetition becomes a critical strategy to explore the grey zones between, for example, fact and fiction, original and copy, ruin and repair.

These are pressures that – in some form or other – Palestinians deal with on a daily basis. From “facts on the ground” and the viability of a Palestinian state, to the cycle of violence and reconstruction. Origin and authenticity are major notions in the “who was here first” claim to the land argument between Palestinians and Israelis. Still, repetition and seriality can be used as a strong artistic and political tactic to highlight Palestinian presence.

Noor Abed, The Air Was Too Thin to Return the Gaze, 2016. Video stills. Image courtesy of the artist

I’ve been wondering about the title of the exhibition, Pattern Recognition. It comes with strong connotations such as machine learning and sci-fi novel. So why did you chose this title?

Well I was trying to think of a title that would on the one hand highlight the motif of repetition but would also trace a lineage from the past, to the present and the future. I am a big fan of William Gibson’s cyberpunk writing, so his novel Pattern Recognition came to mind, purely by way of association. However, there’s definitely a speculative quality to many of the works. Noor Abed’s project is all about trying to piece together information on the sighting of a UFO in the West Bank village of Bir Nabala. Asma Ghanem’s audio performance combines electronics with the sounds of war in a really interesting way.

Ruba Salameh, يم/Ym/ Yamm/ (open sea), 2016. Video still. Image courtesy of the artist

In her video Ym/Yamm/(Open Sea) Ruba Salameh brings together what is at the present moment a geographic and political science fiction: the sea at Gaza, the sea at Tantoura within the 1948 borders and Jerusalem all in one image. And also Aya Kirresh’s investigation of the use of concrete in Palestine by looking at the properties of cement mixtures throughout history is open-ended.

On a more tongue-in-cheek level I wish for this show to reconstitute old and familiar patterns and become an emancipatory tool for articulating a alternative imaginary. This being said, I am well aware that there’s a darker sub-text to the title that refers to military technologies of control and discipline. And though this is not overtly present in the exhibition, this is very much the reality the artists live and work in.

Aya Kirresh, a concrete ode to history, 2016. Concrete cylinder made out of poured layers of different historical mortar mixtures. Image courtesy of the artist

Aya Kirresh, a concrete ode to history, 2016. Freely formed sculptures of various mortar mixtures on the curing table. Photo by: Dia Joubeh

I obviously know far less than you do about Palestine. But it feels like the Palestinian identity is very fragmented because of geographical constraints and because of forced displacements. Talking about the artists, you mentioned in a previous email conversation we had “Their experience is very different from a 1948 Palestinian with an Israeli passport or someone with Jerusalem ID. I’ve had to switch realities every time, working with these artists.” Could you expand a bit on these experiences? What realities does a Palestinian artist have to face in their international career if they are from Gaza, Jerusalem, the West Bank or live as a refugee somewhere else?

I would say that freedom of movement (mobility), security – in different degrees and kind – very much determine the types of access and possibilities available to Palestinian artists. For example, for a Palestinian artist with an Israeli passport it is much easier to obtain visas and travel abroad. If they want to see shows throughout the whole of Israel and study at Israeli institutions, they can. The downside is that it is very difficult – if not impossible – for them to travel throughout the Arab world, except for Egypt and Jordan, countries with a peace treaty with Israel.

And then there’s the example of Majdal Nateel, who lives in Gaza. I could not get her, or her work out of Gaza. The Israelis just did not give her a permit. We had to reproduce her twenty-six gypsum sculptures, and while we did our utmost best and the sculptures look great, it will always miss the artist’s personal touch. Worse is that she will not be present at the opening of her own show and will not be able to meet with curators, journalists and her peers.

Another example is Somar Sallam, born and raised in Damascus, and now a war refugee in Algeria. She made her first ever video and being located in a small town hundreds of kilometres from the capital she had to work with a video editor in Beirut. Working remotely like that is always difficult. Also Somar will not be able to come to Ramallah for the show. I do find these stories heart-breaking and it really pains me they will be unable to attend the show and that I have only met with them over skype and email.

Majdal Nateel’s gypsum pillows at Dar Saa. Photo: Nat Muller

Majdal Nateel, Dream Is Possible, 2016. Sculptural installation, details. Gypsum and earth. Image courtesy of the artist

Majdal Nateel, Dream Is Possible, 2016. Sculptural installation, details. Gypsum and earth. Image courtesy of the artist

Majdal Nateel, Dream Is Possible, 2016. Sculptural installation, details. Gypsum and earth. Image courtesy of the artist

Of course, i’d also like to ask you about any other challenges you have encountered there while curating and setting up the exhibition. I suspect that curating a show in Ramallah might be different from curating one in Amsterdam. Could you share some of the difficulties and rewarding moments that have paved your work there so far?

It has been very rewarding working so closely with these young artists, gaining their trust and mentoring them. I am always impressed with the resilience I find in places like Palestine and the insistence to produce art, often against the odds. That is in and by itself a political act. Though I have worked in the region for over a decade, it is still challenging working on a project like this. One of the reasons is the one cited above: Palestine’s fragmented geography and the difficulty of mobility. This also translates in limited resources, from sourcing the right audio-visual equipment or other materials, to certain types of expertise and know-how. Due to the volatility of the political situation and possible closures, you never know who will make it to the exhibition as far as audience goes.

It is difficult to write about Palestine without mentioning demolition, war, occupation, displacement, drones and discrimination, but there are also moments of lightness and beauty in the works exhibited. Could you tell us about the hope, happiness and positive messages in the exhibition?

Absolutely! Producing art under these trying circumstances is already a message of hope in and by itself. What I wished for the exhibition and the individual works was for them to convey politics through poetics. I do think we have managed to do that.

Lately I have been quoting this phrase by Antonio Gramsci quite a lot: “The old world is dying, and the new world is struggling to come forth; now is the time of monsters.” I feel that Gramsci’s words, written when he was languishing in Mussolini’s prison in the 1930s, describe our unruly times very well. It is important to insist that other worlds, other imaginaries, are possible in these times of monsters.

I think the show will tour after Ramallah. I’ve just read that it is going to be exhibited next year at one of my favourite art venues in London, the Mosaic Rooms. Are there any other cities where we can hope to see the show?

Not yet, but would love to hear your suggestions, Régine!

Thanks Nat!

The A.M. Qattan Foundation’s Pattern Recognition: Young Artist of the Year Award (YAYA) opens on October 8–31, 2016 at Beit Saa, Beit Saa, a traditional house in the centre of Ramallah in Palestine .

The exhibition will travel to the Mosaic Rooms in London 20 January to 25 March 2017.