Queen’s Coat of Arms, in Neon, 2014. Photo by Luke Hayes

Queen’s Coat of Arms, in Neon, 2014. Photo by Luke Hayes

Photo by Luke Hayes

Photo by Luke Hayes

In the playhouse, as in the courtroom, an event already completed is re-enacted in a sequence which allows its meaning to be searched out. […] The courtroom is, or should be, a theatrical space, one which evokes expectations of the uncommon. […] Theatrical effects are such dominant factors in the physical identification of a courtroom that their absence may raise doubts about whether a court which lacks a properly theatrical aspect is really a court at all.

Milner S. Ball, Caldwell Professor of Constitutional Law, University of Georgia

Lawyers learn their lines before their performance, witnesses are given advice about how to play their roles, the judge intervenes when the rules (or should we say the script) are not respected. Meanwhile, the audience sits on the side to enjoy the show.

The architecture of modern courtrooms brings justice and fiction drama even closer to each other. The International Crime Court in The Hague, for example, is equipped with cameras, microphones and sound proof sheets of glass that separates the audience from the main protagonists of the trial. In doing so, the choreographic structures of the court are becoming separated and externalised through the medium of video feeds shot from multiple sight lines, artificial viewpoints and mechanical movements.

Objection!!!, the latest work of artist, writer and film-maker Ilona Gaynor, pushes the court strategies and dramatizations to their most cinematographic limits. Using a series of models, objects, images and a fictionalized case in which a tv National Lottery draw is fixed, Gaynor exposes how the language of film-making manipulates the way a case is presented to the court and how it is understood by it. According to the whim of the team that scripts, shoots then edit the trial, the unfolding of a court case could thus be made to look comical, suspenseful, romantic, tragic or even satirical.

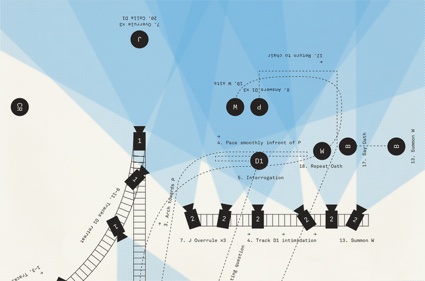

Camera Move Sequence, 2014

Camera Move Sequence, 2014

Among the pieces on show is a courtroom diorama the director would use to plan the filmic direction of the trial, a green Chroma Key Set designed to be positioned as needed and edited out in post-production, a show reel that illustrates cinematographic courtroom drama, an elaborate drawing that maps out the location of the cameras, dolly tracks and people required for the shooting length of a real time testimonial deposition, etc.

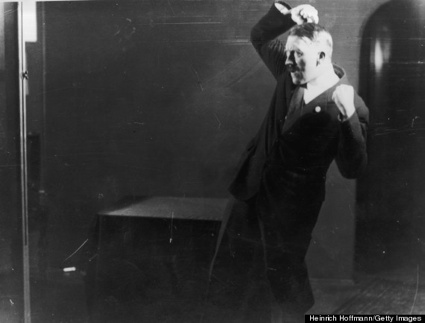

I particularly liked the photographic ‘documentation’ of a lawyer practicing persuasive gestures in preparation for a trial. The images are inspired by 1925 photos showing Adolf Hitler rehearsing his oratory.

The Lawyer, 2014

The Lawyer, 2014

The Lawyer, 2014

The Lawyer, 2014

Hitler rehearsing his speech in 1925. Photo by Heinrich Hoffmann

Hitler rehearsing his speech in 1925. Photo by Heinrich Hoffmann

Objection!!! is part of Designers in Residence 2014: Disruption, an exhibition that showcases the work developed by young designers during their residency at the Design Museum in London. I interviewed Ilona a few weeks after the opening of the show:

Hi Ilona! The starting point of the project is the new courtrooms built by architects where the jury is seated in a separate room. Is that already happening? And what motivates the change in architecture?

It is to an extent, with jurors becoming separated by glass and mirrors with live camera feeds and sound to accompany them. There was a surge in European courts that were being retrofitted into pre-existing office buildings, to save resources (and sometimes for safety of civil unrest) during late 90’s and, the use of camera’s, audio/video feeds is now becoming common practice and is considered state of the art.

The international Criminal Court, in the Hague operates as a very bizarre enclosure, scattered with cameras, positioned at varying heights around the room, their lenses sight and proximity fixed upon on the faces and edges of tables, glasses, mirrors and reflections all screening on live fed monitors to the both the prosecution and defence. These cameras intercut each other at moments pivotal of play, documenting the dialogue and sequence of events from much higher heights then those of eye level.

A view of the courtroom at the International Criminal Court in The Hague. Photo ICC/Flickr

A view of the courtroom at the International Criminal Court in The Hague. Photo ICC/Flickr

Court Diorama, 2014. Photo by Luke Hayes

Court Diorama, 2014. Photo by Luke Hayes

Court Diorama (Detail), 2014. Photo by Luke Hayes

Court Diorama (Detail), 2014. Photo by Luke Hayes

The piece that attracts the most attention in the museum show is probably the elaborate diorama. Could you describe it, what happens there?

The diorama depicts the redesign of a courtroom, the UK crown court to be exact. The geometry of the courtroom was redesigned with the audience in mind; the imagined viewing sightlines to be much more acute then they would normally be; the seats would be positioned as ascending podium steps (the kinds that you see at sports stadiums) to enhance the viewing experience.

The diorama itself is designed to act as a vehicle with which the ‘event’ or ‘show’ aka ‘the trial’ inside courtroom can be plotted and pre-enacted cinematically by the director and producers before it starts, much like theatre rehearsals or pre-recorded live audience TV shows.

The model was designed to be self-assembled, by easy slotting conjoining walls and furniture.

It also comes with a kit of parts that consist of prefabbed folding camera equipment such as: camera’s, dolly rigs, tripods, microphone stands, audience participation signs such as “boo” and “applause” and a set of dramatically posed lawyers and corresponding court room furniture.

To put the diorama in context, dioramas are frequently used between stage / film directors to communicate to actors and production staff. It is used as a plan section for the action that will occur, the sequence in which it happens and what in spatial floor capacity. This work is very much about the positions, sightlines and choreography of people in space and time… in this regard the performance of the court has a lot in common with cinema. The curatorial voice of this work is for the audience to engage in the exhibition from a directorial perspective. What is exhibited, is the anticipatory tools (plans, drawings, scripts, imagery) with which a director would use to shape the production and this case the unfolding of a trial or ‘courtroom drama’.

The Lawyer, 2014

The Lawyer, 2014

The Lawyer, 2014

The Lawyer, 2014

I’m quite curious about the fact that you chose to explain the work using objects. That’s not unusual in a design museum of course but you are openly influenced by cinema, your work often refers to it, you hired an actor and there are indeed films in the show but they are not yours. So why didn’t you just make a video to explain Objection?

I’ve got a strong aversion to films that’s sole purpose is to explain a work. For some reason it’s becoming common practice in design (especially when referring to objects) that the designer needs to reveal the ‘imagined’ interactivity of the ‘objects’, in some candidly scarce scenario.

For me, I actually tend to get accidentally commissioned to make objects; I don’t even really value objects and often find objects hard to engage with, because somehow they tend to lack rhythm or sequential value. I see my work as studies, or compositions that try and allude to a balancing act of arguments or sequential chapters as you may have noticed I often index the ‘objects’ or give them a sort of taxonomy or textual story with which to engage with.

Cinema for me is a common ground with which the fantasies of popular culture are often revealed in much more interesting ways then most other mediums, films allow us freely to wonder around the unimaginable in ways that are contextually and textually rich. My work is often tiptoeing along the edge of this medium because I believe the interrelations between cinema and topics I often pivot around are inextricably linked: aesthetically, contextually and culturally. I am actually this year moving my practice much more into the film going forward, both professionally and personally.

The films that you are referring to in ‘Objection!!!’ are a series of edited clips taken from TV dramas and films that depict the courtroom on screen as a scene or sequence, spanning across the last century of TV and cinema. The purpose of this film is to put my argument into a broadly understood context… the collectively memorised experience of the courtroom, which for most of us, has been experienced through a series of lenses rather then first hand. The film of edited sequences also reveals to the audience the stylistic differentiations between filmic genres, revealing how hard it becomes to remain objective as a pervasive viewer (in this projects case, the jury) when a sequence of camera cuts, pans, soundtracks intertwine. It would be very disturbing to witness (or watch) a case dealing with violence or rape depicted accidentally or not as a comedy for instance; the viewer’s perception and adjudication could sit solely on the head of a deft handed technician. Of course this is an extreme example, but we are much more conditioned to filmic languages, no matter how subtle they are, than we think. A fast zoom to face shot for example is a classic attribute to comedy filmmaking.

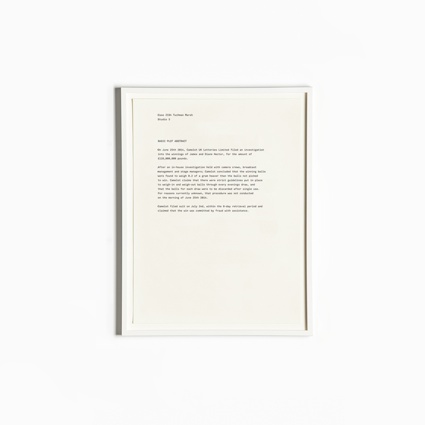

Basic Plot, Case 2194, 2014. Photo by Luke Hayes

Basic Plot, Case 2194, 2014. Photo by Luke Hayes

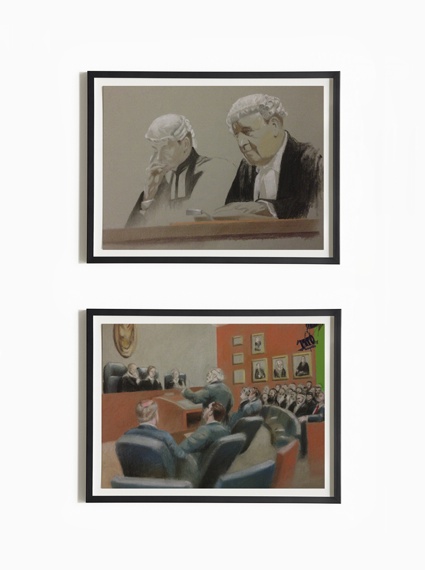

Courtroom Drawings, 2014. Photo by Luke Hayes

Courtroom Drawings, 2014. Photo by Luke Hayes

I was reading the interview you did with Shona Kitchen for the Designers in Residence catalogue. I really liked the way you define your work as designing ‘ruses’. Could you explain what you meant by that (since not everyone has the catalogue in their hands)?

I suppose what I meant by that (although actually not so much in this project) is that I’m interested in taking pre-existing functioning models or systems that often serve to exploit the misfortune of others (legally or sometimes illegally), in some form of monetary or political bargaining and use them in ways to turn it inwards on itself. For example the only way to counteract a trap; is to use another trap, which triggers the setting of a 3rd trap, then a 4th and so on.

It is within these terms that I define my practice of design. I would say that I design ‘ruses’ as a stratagem to plot, to plan, to scheme, as ways to imagine the conceivably unachievable but very logistically possible.

My work often uses design as a vehicle to manoeuvre the arrangement of material in space and over time to pursue an examination of the mechanisms of risk assessment, financial calculation, and rather more literal, legal forms of judgement, in order to generate new situations events or moments to invoke an aesthetic of precision, by really obsessing over narrowing margins of space and time, where exactness matters and becomes a force (I define as design) in its own right.

Also my work often takes form as an anticipation of another form, as a pretext often constructed to allow something else to happen or to be imagined.

My commercial work under my company name The Department of No, uses this practice in much more commercial spheres such as law enforcement, legal planning, crime prevention and script plausibility studies. The ruses directly relate when cross contaminating commercial work with exhibitions and consultancy, they all amalgamate, the fiction feeds the real world and vice versa.

For example I’m currently setting up a practice of licenced Private Investigators to operate in an office located in West Hollywood in Los Angeles, to investigate civil disputes across the city that repeatedly plays itself. The pretext being to write and direct a play of experiences and cases (individuals case plaintiffs unrevealed of course), but we will be operating as a real firm with real clients, attesting to real legal cases.

Photo by Luke Hayes

Photo by Luke Hayes

Photo by Luke Hayes

Photo by Luke Hayes

We live in a time of state control, secrecy and surveillance. But by turning a trial into entertainment, you remove some of the gravitas of the justice system and leave the procedures and interpretation of a trial into the subjective hands of a film director. I’ve just been reading articles from last year about the introduction of television cameras into UK courts to film the sentencing of serious criminals. There was a lot of debate around losing some of the ‘mystique’ of the courtroom vs helping “the public re-engage with the criminal justice system”. Is that something you’d like to comment on?

I’m not sure the ‘mystique’ of the courtroom has ever really entered the minds of most, I say this though however because we have been conditioned to the action of the court, its demeanour, atmosphere and so on through television, film etc. Of course these are highly dramatized, with little or no legal references alluding to the true nature of the law but oddly, legal dramas are some of the highest rated shows on television… the sexed up Ally McBeal was supposedly responsible for a boost of people studying law during the early 00’s.

I think there’s a really odd disconnect between the perceivable “public re-engaging with the criminal justice system” and actual engagement with the issues that ensue due to pervasive camera’s in the courts. The Oscar Pistorius trial was undoubtedly entertaining, however the engagement was only of merely entertainment mixed with a public lust for blood of a ‘murderer’ to be brought to ‘justice’ at the viewing onslaught of a booing crowd. It seems to be taking form as a contemporary Roman games, I’m not sure how to feel about that, it requires both a smirk and a exhale of disgust. But I think the ‘vs’ in the articles you were reading were perhaps in the wrong place. The more concerning question is how the cameras will inevitably affect the trial and veracity of testimony itself rather then jog the public’s perception.

Thanks Ilona!

Ilona Gaynor is an artist, writer and film-maker. She is also the founder of research studio The Department of No and teaches digital + media students “how to tell better stories” at Rhode Island School of Design.

Designers in Residence 2014: Disruption is at the Design Museum in London until 8 March 2015.