A couple of weeks ago, I caught the last moments of the exhibition of the finalists of the 5th edition of the Mario Merz Prize, art section. Associated with the Fondazione Merz in Turin, the Mario Merz Prize is dedicated to artists and musicians “whose creations convey the qualities of generosity of thought, social awareness and original research.” The previous winners of the art section of the prize are Yto Barrada, Bertille Bak, Petrit Halilaj and Wael Shawky.

This year’s selection was solid and diverse, with five artists looking at different forms of slow violence: mechanisation, the oppression of trans bodies, the legacy of colonisation, racial discrimination and rising social inequalities. I’ll start with my favourite work in the show:

Mohamed Bourouissa, Généalogie de la Violence, Film, 2024

Mohamed Bourouissa, Généalogie de la Violence, Film, 2024

Mohamed Bourouissa, Généalogie de la Violence (trailer), 2024

A racialised young man is quietly chatting in a car with the girl he recently fell in love with. For no apparent reason, the police interrupt their conversation and subject the man to a “random” identity check. The policemen remain polite. They are not doing anything illegal. Nothing, however, justifies the frisking and humiliation of the young man in front of his girlfriend. The experience is unpleasant, uncomfortable, even for the viewer of the film. Using 3D scanning, the film recreates the young man’s experience of disconnection from his own body. While the police treat his body as an object to palpate, dominate and surveil, the man’s mind finds refuge in a dream featuring a wild dog.

Mohamed Bourouissa describes the film as “police brutality, with no brutality.” It was inspired by his experience of being regularly stopped by the French police for “random identity checks” when he was younger.

Mohamed Bourouissa, Iriss, 2023. Installation view at Fondazione Mario Merz. Photo: Andrea Guermani

The film is accompanied by a series of sculptures. Made of cast aluminium, they make more tangible the intrusive nature of the police procedure. These sculptures also reveal a point of contact between social bodies and a state body as well as the domination by one body over another.

Bourouissa won the Mario Merz Prize this year. Given his talent, the versatility of his practice and his gift for social comment, this success wasn’t much of a surprise.

Agnes Questionmark, CHM13hTERT, 2023. Installation view at Fondazione Mario Merz. Photo: Andrea Guermani

Agnes Questionmark, CHM13HTERT, performance and installation at SpazioSERRA curated by The Orange Garden Milano 2023

Agnes Questionmark’s delicate marine creature floats among cables and medical straps. She looks like she is trapped inside the metal structures. She is what the artist calls “a transpatient”, someone who is transgender or transhuman. But probably both at the same time. With her human upper body and her tentacles, scales and fins, she can’t exist outside of the medical and scientific machine. For now. CHM13HTERT was first shown as a performance. In 2023, the artist spent 12 hours per day suspended inside the structure. Travellers going through the Lancetti railway junction in Milan would then stop to watch her and take photos.

The beautiful creature was inspired by the possibility of using genome editing techniques, surgical operations and artificial reproduction processes to create new beings and embrace diversity. Humans are already in the process of becoming more artificial, hybrid and queer, but if they have the ability to interfere even further with the course of evolution, what types of bodies could we engineer? Would we become a new species by modifying our DNA or by combining it with that of other creatures? Would it make us closer to the rest of the living or would it further increase the gap between us and other creatures? Could we then reach a state that would be “beyond the human”? Would we then be monsters or vectors of progress for society?

The work celebrates transgenderness and uses it as a tool to subvert the power structure. By complicating traditional notions of identity and humanity, CHM13HTERT aims to challenge biomedical institutions which impose standards, controls and surveillance over bodies, especially transgendered bodies.

Anna Franceschini, What Time Is Love, 2018

Anna Franceschini, What Time Is Love, 2018

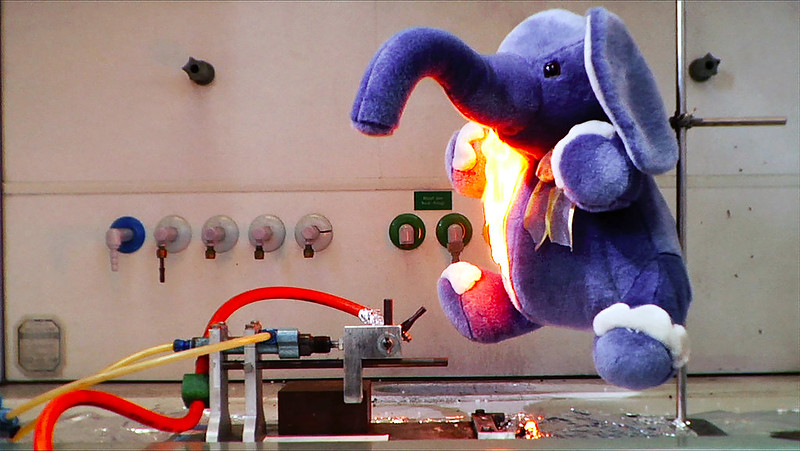

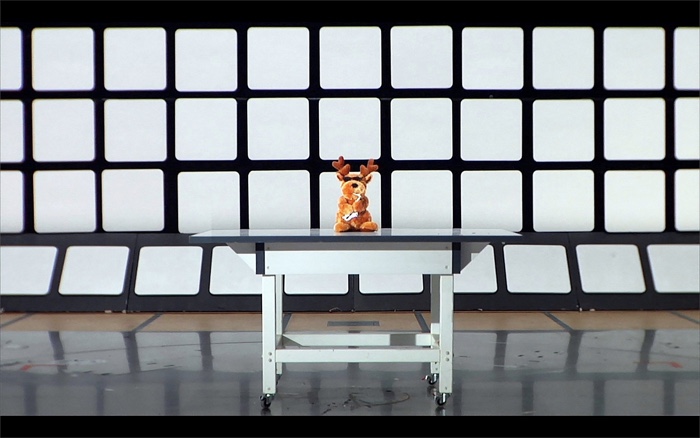

TÜV (Technischer Überwachungsverein, German for Technical Inspection Association) is an independent company that tests, inspects and provides European certificates of suitability to goods and technological commodities. Anna Franceschini travelled to its Nuremberg headquarters to shoot a video showing how toys and other products for small children are put to the test. Crushed, compressed and burnt, plush reindeer and toy pandas are exposed to brutal stress tests and mechanical apparatus. A colourful violence necessary to ensure that the toys are deemed worthy of filling our shop windows.

The video does not question EU safety standards, but it invites us to reflect on the general concepts of standards and suitability and the effort that goes into making a consumer good for a child (or an adult) who may tire of it after a few minutes.

Anna Franceschini, All Those Stuffed Shirts, 2023

Anna Franceschini, All Those Stuffed Shirts, 2023. Installation view at Fondazione Mario Merz. Photo: Andrea Guermani

There’s even more irony in All Those Stuffed Shirts, an installation consisting of seven automatic ironing machines, called dressmen, which have been algorithmically “re-educated”. Using their only means of expression, the air, the dressmen quietly inflate and then dramatically collapse following a mechanical ballet devised by the artist. The movements of the technical objects are a bit cartoonish, halfway between a ballet and a GIF animation.

Anna Franceschini uses the sculptural nature of the ironing machines as readymades to explore the double identity of the industrial object: pitiful mechanical helper without head nor legs, or freak that can take a life of its own.

Elena Bellantoni, On the breadline, 2019

Elena Bellantoni, On the breadline, 2019

Elena Bellantoni, On The Breadline, 2019. Installation view at Fondazione Mario Merz. Photo: Andrea Guermani

Elena Bellantoni, On the breadline, 2019

Elena Bellantoni, On the breadline, 2019

Elena Bellantoni, On the breadline, 2019

As we come marching, marching, unnumbered women dead

Go crying through our singing their ancient song of Bread;

Small art and love and beauty their trudging spirits knew—

Yes, it is Bread we fight for—but we fight for Roses, too.

These are lines from a poem published by James Oppenheim in 1911. Inspired by the speeches of women’s suffrage activists and syndicalists such as Rose Schneiderman and Helen Todd, the words talk about the right to something higher than subsistence living.

Elena Bellantoni travelled to Italy, Greece, Serbia and Turkey to film groups of women singing the protest song Bread & Roses in their native languages. The settings of the performances are an abandoned airport, a Brutalist flat building, a former factory, an old shipyard, a former factory. The derelict buildings embody a past characterised by faith in a certain idea of “progress” and a present made of precariousness and uncertainty. The future of these spaces is uncertain. Maybe they’ll be revamped into art spaces or shopping malls. Maybe they will just be dismantled.

Bellantoni chose these four Mediterranean countries because they exemplify the breadline, the poverty line but also the line of bread that have marked their histories. In their cultures, bread does not only represent a moment of conviviality and exchange, it is also linked to popular uprisings and protest for social equality.

Voluspa Jarpa, The Extinction project, 2025. Installation view at Fondazione Mario Merz. Photo: Andrea Guermani

Voluspa Jarpa handcrafted installation exposes the connections between historical colonialism and contemporary crises. She layered temporal membranes that synthesise three phases of the American continent. The outside layers present contemporary cartography. The second layer is dedicated to the coup d’état that hit Latin American countries in the 1950s, 60s and 70s. The final layer exposes the ongoing oppression of the ancestral people of the continent.

The idea for the installation stems from a scientific paper describing the climate effects of the massacre of the indigenous population of the Americas. According to the study, the massive loss of life that followed the conquest of the continent led to a huge surfaces of abandoned agricultural land being reclaimed by fast-growing trees and other vegetation. This pulled down enough carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to cool down the planet.

Jarpa’s work interconnects the geographical and historical layers to show how one event happening in one place can eventually have tragic reverberations in another and across time. Her installation makes visible the “slow violence” that destroys land and communities over the long term through mechanisms of expropriation and environmental devastation.

I’m just going to mention one of the works that was on the short-list of the Mario Merz Prize, music section:

Domenico Antonio Mancini, Il nostro zucchero quotidiano (Our daily sugar), 2025. Photo: Andrea Guermani

Domenico Antonio Mancini travels across the city on a Piaggio Ape, a three-wheeler associated with fruit and vegetable vendors in southern Italy. Instead of sales messages, the megaphone mounted on the utilitarian vehicle broadcasts texts by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish.

The fifth edition of the Mario Merz Prize, art section, was curated by Giulia Turconi. It was on view on 11 June until 21 September 2025 at the Fondazione Merz in Turin.