Previously: Manifesta 9 – The Age of Coal.

Let’s head back to the mine for a quick review of the 9th edition of Manifesta, the European Biennial of Contemporary Art which is held this Summer in the former Waterschei coal mine in Genk, Belgium.

While floor one and two were focusing on the history of the exploitation of coal in the Limburg region and in the rest of the “western world”, the top floor of the crumbling art deco industrial building is filled with contemporary artworks that address de-industrialization and post-industrialization. As you can expect, many of the works come with a sense of doom similar to the one experienced by local communities when the mine closed in 1987. The artists selected for the biennial confront issues such as the dematerialisation of production, new forms of labor, the loss or transformation of social ideologies, the challenges of creating energy, counterfeit luxury goods and the parallel economy it generates, etc. Unfortunately, post-industrial practices are more than the pretext for an art exhibition, they also crucial motors of the current socio-econo-political climate and they are affecting or will soon affect the life of every single visitors.

Magdalena Jitrik, Revolutionary Life, 2011-2012

Magdalena Jitrik, Revolutionary Life, 2011-2012

Manifesta 9 Preview & Opening. Photo Manifesta

Manifesta 9 Preview & Opening. Photo Manifesta

Manifesta 9 (Graphic Design by thonik). Photo Manifesta

Manifesta 9 (Graphic Design by thonik). Photo Manifesta

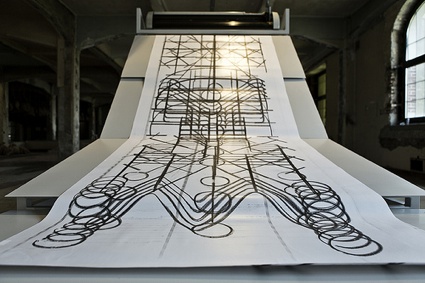

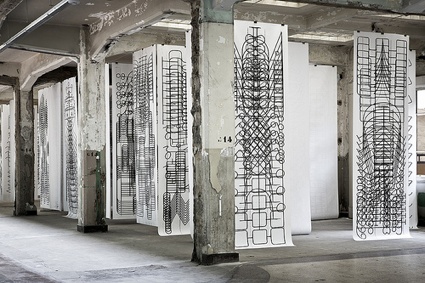

One of the most impressive and colossal pieces in the show is Carlos Amorales‘ Coal Drawing Machine which draws what looks like elegant electronic circuits continuously throughout the run of the exhibition. Well maybe not ‘continuously’ because it wasn’t turned on when i visited. Long strips of print-outs are cut and hung from the ceiling to form a delicate and fascinating maze.

Carlos Amorales, Coal Drawing Machine, 2012

Carlos Amorales, Coal Drawing Machine, 2012

The machine receives transmissions from an unseen and unknowable source but instead of synthetic toners or dyes, the machine draws with charcoal. The Coal Drawing Machine questions the tension between the hand made quality of the traditional coal drawings and the fact of these being industrially produced by a machine.

A couple more images because that machine was one of the highlights of the show for me:

Carlos Amorales, Coal Drawing Machine, 2012

Carlos Amorales, Coal Drawing Machine, 2012

Some of the artists took the walls, corridors, floors and other architectural elements of the Watershei building as the point of departure of their intervention. They did it so unobtrusively and delicately that visitors run the risk of walking by them or over them without even realising it. Takes these three artworks for example:

Rossella Biscotti‘s Title One: The Tasks of the Community is part of the floor of the exhibition space and you’re free to traipse all over it. The material use comes from a disused nuclear power station in Lithuania. On December 31, 2009, despite popular resistance and economic consequences, Unit 2 of the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant was closed under pressure of the European regulatory bodies. As part of the dismantling process, materials from the site were put up for auction as what the Ignalina plant’s website described as “unnecessary property.” Biscotti attended two public auctions, acquired lead and industrial copper cables, and used them for her installation. The lead is part of the floor-based sculpture, the copper was recycled into new electrical wires to supply electricity to the show. These gestures allude to the climate of social concern around the role of nuclear energy in post-Cold War Europe, but they also create a short circuit between distant social processes that typically remain opaque to the citizenry, physically inserting art, its institutions and audiences into the complex life cycle of the productive system.

Rossella Biscotti, Title One: The Tasks of the Community, 2012

Rossella Biscotti, Title One: The Tasks of the Community, 2012

Nemanja Cvijanovic’s work The Monument to the Memory of the Idea of the Internationale starts with an unasuming music box that will remain silent unless a visitor comes closer and activate its handle (the contemporary art world calls that ‘interactivity’.) The instrument plays the Internationale anthem. The music is picked up by a microphone, travels to the speakers in another room where it is in turned picked up by other microphones, etc. The music ends up being played outside by a big pyramid of speakers. The revolutionary anthem gains in volume as it travels through the site but somehow, some of its power also gets diluted in the process. Video.

Nemanja Cvijanovic ́, Monument to the Memory of the Idea of Internationale, 2010

Nemanja Cvijanovic ́, Monument to the Memory of the Idea of Internationale, 2010

Nemanja Cvijanovic ́, Monument to the Memory of the Idea of Internationale, 2010

Nemanja Cvijanovic ́, Monument to the Memory of the Idea of Internationale, 2010

Nemanja Cvijanovic ́, Monument to the Memory of the Idea of Internationale, 2010

Nemanja Cvijanovic ́, Monument to the Memory of the Idea of Internationale, 2010

Oswaldo Maciá collaborated with a perfumer to fill a dark and humid corridor with a smell that is meant to evoke failure. But because Maciá’s installations also make use of sounds to synaesthetic experiences, he didn’t just create a smelly corridor, he made an ‘auditory olfactory composition.’ There is a sound element to his work and it nods to the rise of heavy (and noisy) machinery of the Industrial Revolution. The sounds of five different anvils being struck by hammers in distinct echo in the corridor across ten separate channels of sound arranged along the corridor.

Oswaldo Maciá, Martinete, 2011-2012

Oswaldo Maciá, Martinete, 2011-2012

Manifesta might have a one and only focus (industrialisation in all its pre-, post and de- forms) and a unique venue but its breadth runs wide. Hopefully, i’ll find more time in the coming days to come back to it. If i don’t, here’s a shortlist of the works i discovered:

Maryam Jafri‘s short video Avalon is a remarkable mix of documentary and fiction film.

The story begins in an unspecified Asian country where an entrepreneur (whose face is concealed) describes how he founded a clandestine, million-dollar business that exports fetish wear, with a small start-up investment from his father. The women who work as seamstresses in his small factory believe that they are sewing body bags for the US Army, straight jackets, and accessories for circus animals, though they do have their doubts. The video continues with testimony from an educated textile designer who found herself unwittingly designing for a business with which she does not personally identify, a white collar professional man who is open about his sexual identity and finally, from a woman who performs role play services using the paraphernalia in question.

Based on archival research, observations, and interviews, the video investigates the relationships between entrepreneurship, labour, use value, and the production of both commodities and subjectivities in the current global cultural economy.

Maryam Jafri, Avalon, 2011

Maryam Jafri, Avalon, 2011

Maryam Jafri, Avalon, 2011

Maryam Jafri, Avalon, 2011

Maryam Jafri, Avalon, 2011

Maryam Jafri, Avalon, 2011

Claire Fontaine‘s work The House of Energetic Culture is an adaptation of the neon that once overlooked the House of Culture in Pryiat–nowadays a ghost town located within the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. The sign that was once a symbol of modernity, comfort and culture acts now as a reminder of the blessings and dangers that progress brings upon society.

Claire Fontaine, The House of Energetic Culture, 2012

Claire Fontaine, The House of Energetic Culture, 2012

Tomaž Furlan‘s Wear series of strange contraptions and performances gently deride the routines of modern workers. Their work -whether in office or factories- might be assisted by technology but it is nevertheless as alienating, repetitive and disrespectful of the human body as ever. Video.

Tomaž Furlan, Wear series, 2006-2012

Tomaž Furlan, Wear series, 2006-2012

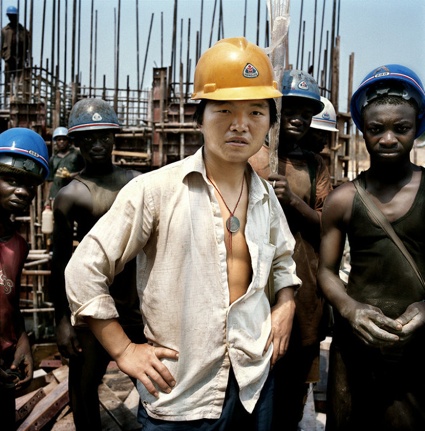

Paolo Woods, Chinafrica, 2007

Paolo Woods, Chinafrica, 2007

Irma Boom & Johan Pijnappel, Thoughts on a Think Book, 2012- 1991

Irma Boom & Johan Pijnappel, Thoughts on a Think Book, 2012- 1991

Ben Cain, Work in the Dark, 2012

Ben Cain, Work in the Dark, 2012

Bea Schlingelhoff, I’m Too Christian for Art, 2012

Bea Schlingelhoff, I’m Too Christian for Art, 2012

Emre Hüner, A Little Larger than the Entire Universe, 2012

Emre Hüner, A Little Larger than the Entire Universe, 2012

Manifesta 9 Preview & Opening. Photo Manifesta

Manifesta 9 Preview & Opening. Photo Manifesta

Manifesta 9, The European Biennial of Contemporary Art, is on until 30 September, in Genk, Belgium.