Over a week ago, i was in Antwerp. My first stop was FOMU, the Photography Museum and one of the few cultural spaces where i’m sure i’ll always get to discover something curious and eye-opening. My intention was to visit the show dedicated to young Belgian photographers and the one about The Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda. After that i thought i’d haughtily snob the MAAN/MOON and make my way to another exciting art space in town. Fortunately, i was accompanied by a friend whose enthusiasm for celestial bodies hasn’t been damped by the current media frenzy about the anniversary of the Moon landing.

Edwin Reichert, People stand in front of a television shop and look through the window to witness the start of the Apollo 11 space mission, Berlin, Germany. Photo AP, via

© Vincent Fournier, Atacama Desert, Lunar Robotic Research (Nasa), Chile, 2017

© Vincent Fournier, Space Odyssey spacesuit#1, Sylmar, USA, 2019

MAAN/MOON is an uplifting exhibition about humanity’s fascination for the Moon. It’s so good that even i, the only person on Earth stupid enough to profess a total indifference for space travel, decided it was worth coming back to it with a blog review.

By mixing science, NASA archives, astronaut’s wives drama, contemporary artworks, humour, poetry and politics, curators Maarten Dings and Joachim Naudts present an enchanting perspective on our only permanent natural satellite.

Here’s a quick tour of some of the works and facts i discovered while i was visiting the exhibition:

Gil Scott-Heron, Whitey On The Moon, 1970

In “Whitey on the Moon,” Gil Scott-Heron brings technological achievements into the context of racial inequality in the USA. Instead of joining the chorus that celebrated the space race, the poet denounces the distressing conditions in which urban African-American communities live and questions the economic priorities of his country.

Scott-Heron wasn’t the only American citizens who challenged the extravagance of a trip to the Moon. Testifying to the US Senate on race and urban poverty in 1966, Martin Luther King declared that “in a few years we can be assured that we will set a man on the Moon and with an adequate telescope he will be able to see the slums on Earth with their intensified congestion, decay and turbulence”.

Katie Paterson, Earth-Moon-Earth (Moonlight Sonata Reflected from the Surface of the Moon), 2007

Earth-Moon-Earth or “moon bounce” is a radio communication system that consists in sending messages in Morse code from Earth to the Moon where it is reflected off the surface and then received back on Earth. The Moon sends back most of the information but some of it can also get lost in the process.

Katie Paterson translated Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata into Morse code and sent it to the Moon. Once back on our planet, the composition was re-translated into a new score, the gaps and absences becoming intervals and rests. The “Moon-altered” piece is played on an automated grand piano.

What makes the work so moving is the way it embraces the distortions, loss and imperfections of the technique, subtly reinventing the sonata and giving it a celestial dimension.

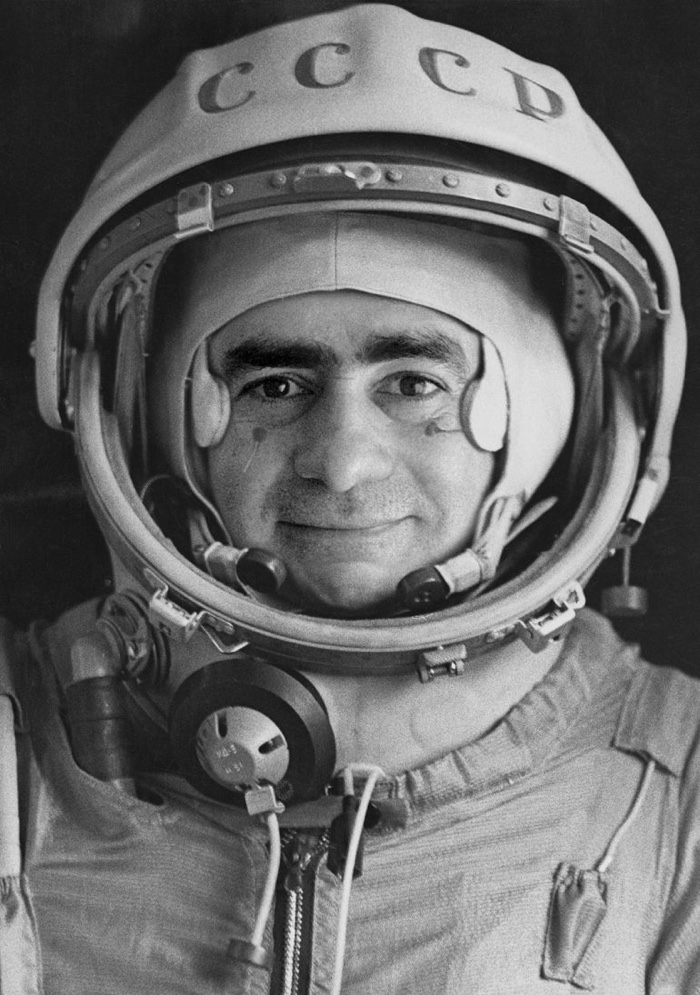

Joan Fontcuberta, Sputnik (Official portrait of the astronaut Ivan Istochnikov, 1997), 1998

Joan Fontcuberta, Sputnik (detail of the installation), 1997

In a series that mixes historical documents and fabricated evidence, Joan Fontcuberta chronicles the tragedy of astronaut Ivan Istochnikov (the closest Russian translation of Joan Fontcuberta), lost in space under mysterious circumstances on October 25, 1968.

Fontcuberta reconstructs the life of the cosmonaut, his childhood, military career, family life and the journey together with Kloka the dog on the Soyuz 2 spacecraft. The artist then shows how Soviet officials deleted Istochnikov from official Soviet history to avoid embarrassment.

On 24 April 1967, cosmonaut Vladimir Komarov was killed in the Soyuz 1 as it re-entered the atmosphere. He was the first man to die during a space mission. In this photo, taken during his funeral, Soviet officials regard Komarov’s charred remains in an open casket. Photo

Paul Van Hoeydonck, Fallen Astronaut, 1971

I had no idea that Apollo 15 had left the first (official) artwork on the Moon during its mission. Fallen Astronaut is a 8.5 cm high aluminium sculpture commissioned by the Apollo 15 crew to commemorate the 14 astronauts and cosmonauts who had thus far lost their lives in the exploration of space. It was placed on the Moon next to a plaque listing the men known at the time to have died.

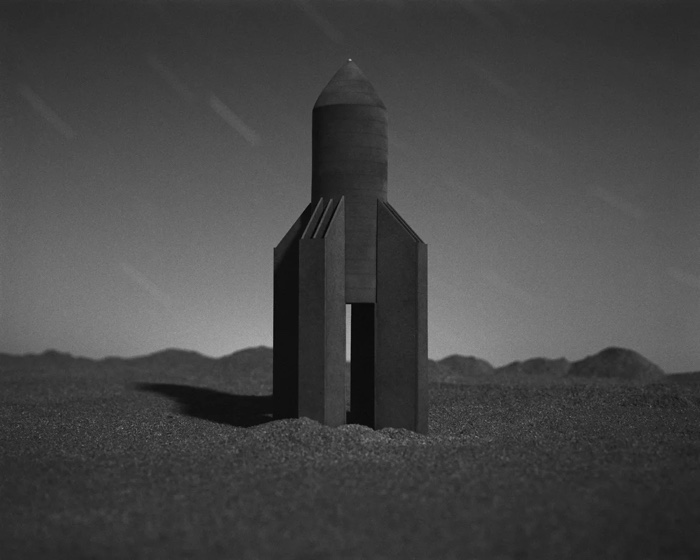

© Sjoerd Knibbeler, Friede, 2017

For the Lunacy project, Sjoerd Knibbeler made wooden scale models of various spacecraft and photographed them by moonlight in an open-air studio. The image above recreates Friede, the fictitious rocket from the first science fiction film to be based on actual scientific research (Frau im Mond, a silent movie by Fritz Lang, 1929).

© Jojakim Cortis & Adrian Sonderegger, Making of AS11-40-5878 (by Edwin Aldrin, 1969), 2014

Photographers Jojakim Cortis and Adrian Sonderegger carefully recreate iconic photographs as miniature 3D models, pulling back the camera to reveal the behind-the-scene construction work. A work that perhaps allude to the Moon landing conspiracy theories.

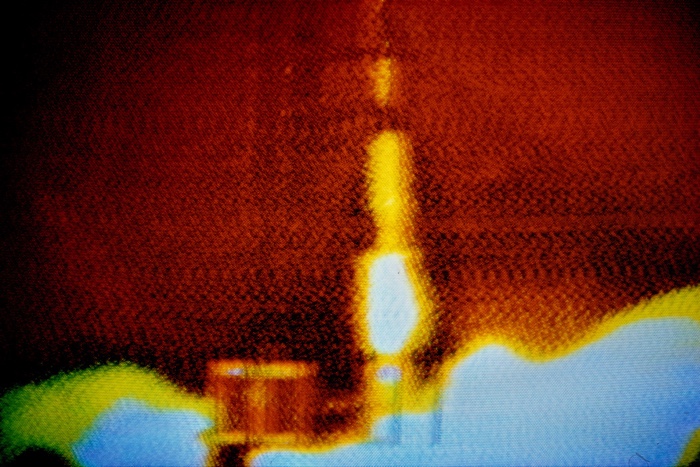

Harry Gruyaert, Apollo XIV on BBC II, from the series TV Shots, 1971

Harry Gruyaert raised controversy when he exhibited his TV Shots for the first time in 1974. He had photographed sitcoms, dog shows, news bulletins, ad breaks, the Apollo flights and other programs as they appeared on television screens at the time. The result is garish, distorted and was seen as a disrespectful assault on both the culture of television and the conventions of photography.

Giorgio de Finis and Fabrizio Boni, Space Metropoliz, 2013

Giorgio de Finis and Fabrizio Boni, Space Metropoliz (trailer), 2013

A former salami factory on the outskirts of Rome, home to immigrants from around the world, is housing an art gallery called MAAM (Museo dell’Altro e dell’Altrove di Metropoliz, in english Museum of the Other and the Elsewhere of Metropoliz).

A few years ago, Fabrizio Boni and Giorgio de Finis collaborated with the residents of Metropoliz on a documentary that follows them as they are building a rocket to go to the Moon. The residents worked to build sets, act as extras, etc. The film is of course also a poignant comment on the issues these individuals face everyday in Italy: discrimination, xenophobia and the threat of being evicted.

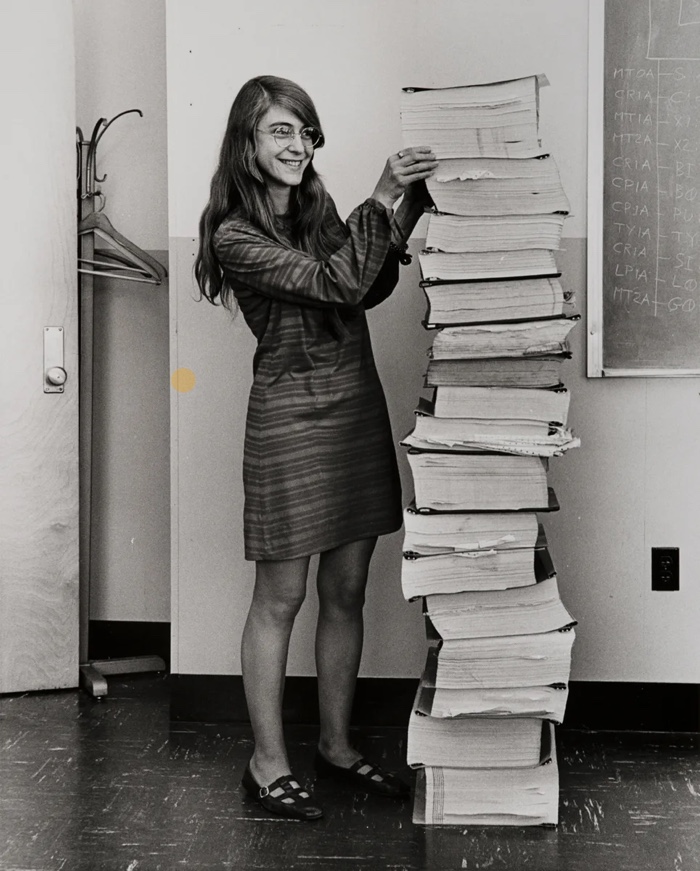

Margaret Hamilton standing next to the Apollo Guidance Computer Source Code, 1969. MIT Archive

American computer scientist Margaret Hamilton and her team at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology wrote the source code which allowed astronauts to land safely on the Moon. An enormous achievement given that, back in the 1960s, the colossal computers were powered by just 72KB of computer memory (a smartphone nowadays has a million times more storage space) and relied upon analogue punched cards for input.

John Adams Whipple, Image of the Moon, 1852

Working with astronomer William Cranch Bond in the mid-19th Century, John Adams Whipple made daguerreotypes of the Moon using a telescope from the Harvard College Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Great Refractor telescope was the largest of its kind at the time, and it took three years for the duo to overcome the many technical and meteorological challenges to achieve a usable image. At the time, the picture was praised throughout the world for being the most accurate and sublime image of the Moon.

Agnes Meyer-Brandis, The Moon Goose Analogue (documentation), 2012

Léon Gimpel, Hyperstereoscopie de la lune, 1923 © Léon Gimpel \ Archive of Modern Conflict

Léon Gimpel used two existing photographs to create the stereo photo above. Both photographs were taken from the Observatoire de Paris with a gap of almost three years (9 May 1897 and 7 February 1900). In 1923, Gimpel converted the images into autochromes. He later used the anaglyph method to give the illusion of a three dimensional image. Two images are displayed on top of each other: a red image for the left eye and a cyan image for the right eye. Wearing special glasses turns the composition into a grey floating Moon.

Lee Balterman, Joan Aldrin sobs with joy and relief as she learns of the successful completion of the husband’s mission, July 1969 (via)

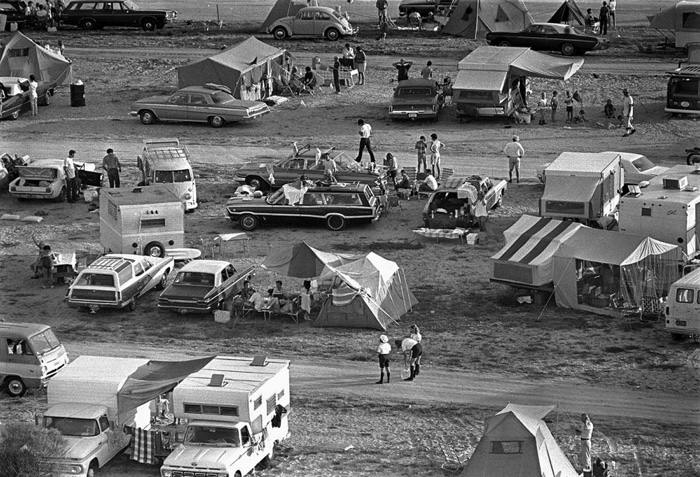

A crowd gathers to watch the launch, Merritt Island, Florida. July 16, 1969. Photo: NASA/Flickr via

Joel Meyerowitz, A young couple sitting on their Plymouth Satellite on the eve of the launch of the Apollo 11. It is estimated that around one million people gathered neat Cape Kennedy in Florida to witness the launch

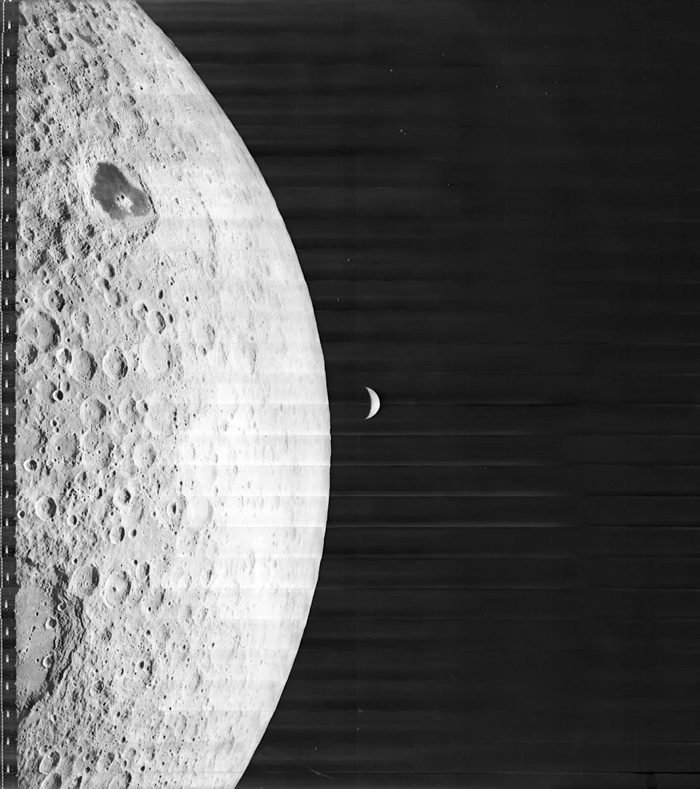

Lunar Orbiter 1 Frame 1117, 1966 © NASA

The Lunar Orbiter programme consisted of five unmanned spaceships sent between 1966 and 1967 to the Moon’s surface and help select Apollo landing sites. The Orbiters were equipped with a system that allowed the images to be developed and scanned on board. While the spacecraft flew over the surface of the Moon, 70-mm long film strips were exposed in a twin-lens camera. The photographs were sent as analogue signals to earth where the strips were assembled into mosaic images.

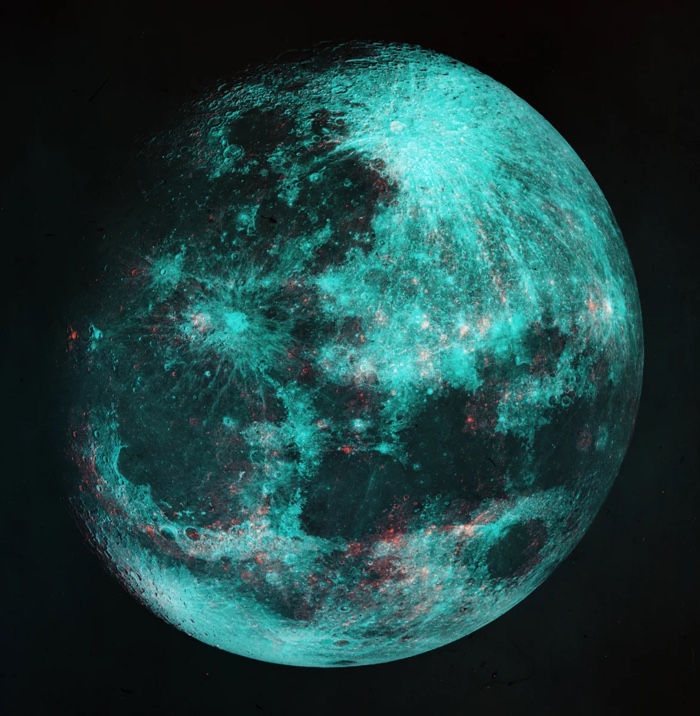

© Roberto Pufleb & Nadine Schlieper, Alternative Moons, 2017

Fritz Goro, NASA engineer Allyn Hazard testing the prototype of a spacesuit, 1962. The outfit was designed by the Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation and was intended for use in the Apollo lunar landing programme. Photo

© Penelope Umbrico, Everyone’s Photos Any License – 654 of 1.146.034 Full Moons on Flickr in November 2015

© Annemie Augustijns, The Moon Poland, 2006

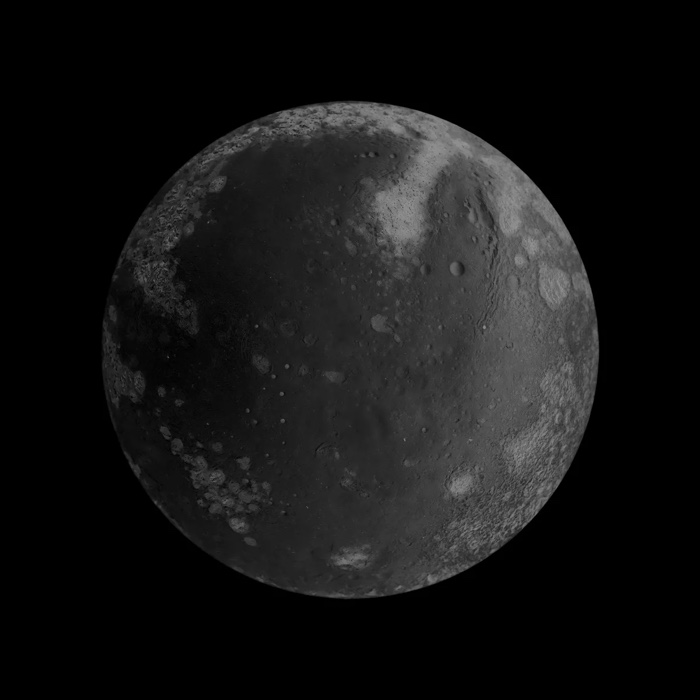

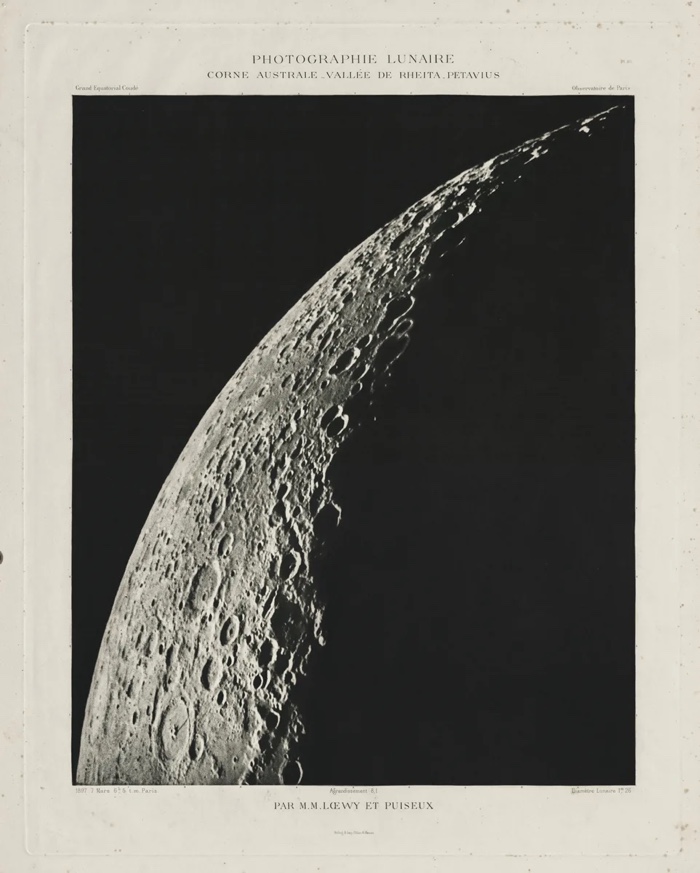

© Pierre Puiseux & Maurice Loewy, Atlas photographique de la lune, 1896 – 1910

MAAN/MOON is curated by Maarten Dings & Joachim Naudts. The exhibition remains open until 6 October 2019 at FOMU, the photography museum in Antwerp, Belgium.

Related stories: KOSMICA: Full moon politics, Should We Colonise the Moon?, The Moon Goose Analogue: Lunar Migration Bird Facility, Interview with ‘We Colonised the Moon’, etc.