The Fundamentals of Sonic Art and Sound Design, by Tony Gibbs, leader of the BA Sonic Arts programme at Middlesex University. (Amazon USA

The Fundamentals of Sonic Art and Sound Design, by Tony Gibbs, leader of the BA Sonic Arts programme at Middlesex University. (Amazon USA

Editors say: The book explores the worlds of sonic arts and sound design through their history and development, and looks at the present state of these extraordinarily diverse genres through the works and words of established artists and through an examination of the wide range of practices that currently come under the heading of ‘sonic arts’. The technologies that are used and the impact that they have upon the work are also discussed. Additionally, The Fundamentals of Sonic Arts & Sound Design considers new and radical approaches to sound recording, performance, installation works and exhibitions and visits the worlds of the sonic artist and the sound designer.

This book is exactly what i needed: a kind of “Sonic Art for Dummies.” It is well written, easy to digest, very clearly structured, and it provides me with some useful tools that will help me understand better the sonic installations i keep encountering in new media art festivals.

Score For A Hole In The Ground, Jem Finer

Score For A Hole In The Ground, Jem Finer

The book attempts to get as close as possible to a definition of sonic art while underlining how difficult the task is given the many forms that the discipline can take and how it spills over into fine arts, performance, music, etc. Oh! and by the way, the title indicates that the book is also about sound design. Actually there’s not much about it, a few pages here and there but as far as i’m concerned that’s not something to complain about.

The first part explores the origins and developments of the genre with a nice timeline and a focus on pioneers such as Edgard Varese, Steve Reich and John Cage. The usual suspects you’d say. And others you would not think about: such as our ancestors who gathered in the caves not just admire paintings. Apparently the paintings were found in locations where the acoustics have unusual qualities which have led some scientists to claim that the places might have been venues for early forms of multimedia events.

The best part of the chapter presents the work of Italian futurist Luigi Russolo and in particular his 1913 treatise The Art of Noises that puts forward an idea revolutionary for the time: there should be no barriers between sounds that have musical or instrumental origins and those who come from the street, the industry or even warfare. He tried to prove his point with his Intonarumori (or Noise Intoners) machines. Each of them produced a particular type of noise, there was the Ululator (the howler), the Crepitatori (the crackers), and the Stropicciatore (the rubber). On April 24, 1914, he conducted the first ‘Gran Concerto Futuristica’ with musicians playing those noise machines. The audience responded by throwing vegetables, booing, hooting and whistling.

The best part of the chapter presents the work of Italian futurist Luigi Russolo and in particular his 1913 treatise The Art of Noises that puts forward an idea revolutionary for the time: there should be no barriers between sounds that have musical or instrumental origins and those who come from the street, the industry or even warfare. He tried to prove his point with his Intonarumori (or Noise Intoners) machines. Each of them produced a particular type of noise, there was the Ululator (the howler), the Crepitatori (the crackers), and the Stropicciatore (the rubber). On April 24, 1914, he conducted the first ‘Gran Concerto Futuristica’ with musicians playing those noise machines. The audience responded by throwing vegetables, booing, hooting and whistling.

The Tri-phonic Turntable (1997), Janek Schaefer

The Tri-phonic Turntable (1997), Janek Schaefer

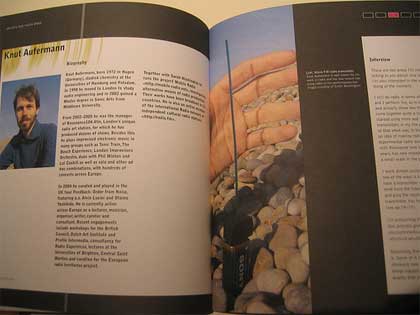

In the second part, the author interviews 5 sound artists, asking them to reflect on their own practice, define it, explain how they work and what their relationship with technology is. The answers to the same question are quite different from one another, and the ways they engage with sonic art range from electroacoustic music, to radio, instrument hacking, kinetic sound sculptures and found footage collages, demonstrating the wide scope encompassed by sonic art. The interviewees are Vicki Bennett, Max Eastley, Janek Schaefer, Simon Emmerson, and Knut Aufermann. Throughout the books, Gibbs also presents the installations and performances of other artists, some i was familiar with, others i was delighted to discover.

3rd chapter was the hardcore one for me. Ok, well… i skipped most of it because it deals with the practical aspects of sonic art, you know… “Working in studio or lab?”, “the role of the computer”, etc. A bit technical as the pages are meant as a “catalyst for the development of individual ideas.” I read some of it and was quite stricken by this quote: A video camera is closer to a microphone operation than it is to a film camera: video images are recorded on a magnetic tape in a tape recorder. Thus we find that video is closer in relationship to sound, or music, than it is to the visual media of film and photography. Says who? Bill Viola, Digital and Video Art.

Urban and domestic incidents “a cup of tea”, Brown Sierra

Urban and domestic incidents “a cup of tea”, Brown Sierra

Part 4 might be my favourite and ought to become the bible of several curators i’m not going to name. The chapter gives basic rules for the exhibition of sonic art pieces, listing the most common difficulties that involve the presentation of such art pieces, especially when the works are presented in the context of a wider exhibition or are not site-specific (dreadful conditions of a white cube gallery). There is also a good deal of emphasis on the preservation and archiving of the sound pieces and a an overview of the installations and performances developed by Tony Gibbs’ students (not much traces of it online unfortunately).

Gibbs is always cautious and prudent when presenting the information. You sometimes wonder where he is standing. He gives several clues to achieve a definition of sonic art for example but not a clear and definite one, just possible threads and elements. Readers have to make up their mind. The strategy is subtle and humble. Some will like it (i do), others would prefer to read strong statements to either adopt blindly or comment on and criticize.

Minus one point for ignoring the blogs. At the end of the book there is a list of online information source. There´s often more info and inspiration in weblogs such as mediateletipos, create digital music or networked music review than in some of the websites mentioned in the book.