Australia, Greece, Canada, Spain, Siberia, Portugal, Italy, France, the Amazon, California, etc. Videos of wildfires have been appearing on our screens repeatedly and mercilessly, as we are moving deeper into a terrifying world of extreme weather events driven by the climate crisis. The images that mark our minds tend to be the ones showing distressed populations, forests in flames, destroyed properties, black fumes, etc. But what about what is beneath the ground?

Wildfires have a significant impact on the soil. The heat of the fire burns the organic matter on the surface of the soil, which makes some nutrients more readily available to the soil while turning others into gases that are lost. Fires also increase the risk of soil erosion, while the heat of the fire can significantly alter both the biome and the physical properties of the soil.

Margherita Pevere, Lament, 2024. Performance and installation. Photo: Romane Iskaria

Margherita Pevere, Lament (trailer)

Margherita Pevere’s Lament explores what happens to the soil after wildfires. By focusing on soil, the performance and installation go beyond the human feelings of sorrow and panic that assault us when we see images of an uncontrolled blaze. The zoom on the usually overlooked element of ecosystems also expands the perspective and provides a safe space to reflect on the ecological grief arising from human-induced wildfires and on the ecosystem changes they triggered by fires.

I didn’t see the whole performance of Lament, but I was lucky enough to watch its rehearsal at iMAL where the performance premiered last year. During the performance, Pevere embodies a hybrid creature of the soil. She contorts her body through organic elements from a wildfire site and underneath glass sculptures containing burnt soil and moss. Her movements are spellbinding. They communicate both grace and pain, agony and beauty. Ivan Penov accompanies the work with a composition on cello.

After the performance, the disturbed soil remains on the floor as a more-than-human deathbed that testifies to a crisis that will be followed by a transformation process. Over time, tiny changes can be observed inside the glass sculptures. The enclosed burnt soil and moss evolve, reminding us that a wildfire is not a cut-off event, but a phenomenon that pertains to the evolution of more-than-human ecosystems.

I left the rehearsal feeling empty. Strangely enough, there was something peaceful in the performance. I perceived the suffering but also the transitory element. I’ve sometimes summoned that feeling of acceptance in the following months when I read the news and fell into despair. I never went through the horrors of a wildfire, but I’ve often felt the urge to remember that “this too will pass”, that humans can be monsters, but that they can also find inspiration and solace in the observation of other life forms.

The Lament project was preceded by a solid preliminary research process that saw the artist collaborate with scientists, policymakers and communities affected by extreme wildfires. The community engagement chapter involved working with people whose lives had been hit by wildfires to ultimately co-create an artwork generated by collective memories and lessons, as a way to share environmental grief, develop resilience and eventually make space for regrowth.

Lament is part of Pevere’s long-term project “untaming death” which explores death from a more-than-human perspective in times of environmental disruption.

Margherita Pevere is an artist whose practice addresses contemporary taboos like death, sex and vulnerability through a queer lens. She kindly found a moment to tell us more about her investigation into post-wildfire ecological processes:

Margherita Pevere, Lament, 2024. Performance and installation. Photo: Romane Iskaria

Margherita Pevere, Lament, 2024. Performance and installation. Photo: Romane Iskaria

Hi Margherita! I don’t know that many artists who work on the topic of wildfire, except perhaps to show its aesthetics and spectacularity. But your work looks at the aftermath of wildfire. That’s not something we think about when we read about wildfires all the time, unfortunately. What motivated you to work on the aftermath of wildfires? In a sense, with all the research and onsite engagement that led to Lament, you did something that not many journalists do.

The drive was exactly to look at what happens after the spectacular wildfire moment is over. Wildfires can be dramatic and dangerous; they are complex and, to some extent, they are also stunning. Which is one of the reasons why they get so much attention when they happen. People tend to get hooked by headlines and big moments, whereas what comes after is mostly overlooked. My artistic practice looks at phenomena that tend to be neglected. To me, they are as interesting as the rest, perhaps even more.

Lament: interview for NaturArchy at iMAL

In the video interview you made for NaturArchy at iMAL, you mentioned something that i found striking and important: you said that you are currently looking for ways to push back against ideas of idealised nature. Why is it important not to idealise nature?

I love nature, of course! But I think we need to be careful about idealizing it as a place of pure harmony. Considering my own European background, I see how this perspective can be problematic – all my reflections here regard the Western world-view. There’s a long history of viewing nature as separate from humans, which goes back to philosophical ideas like Aristotle’s dualism between matter and spirit. Dualisms lead binaries in our culture, like nature vs culture, female vs male, life vs death, art vs science, and so on.

When we treat nature as separate, it becomes something to protect, manage, or exploit. This mindset allows for domination. Various interpretations of nature exist; for instance, mainstream Christian views often suggest human control over other beings, while Romanticism linked nature to the artist’s inner life and the rise of the nation-state. Although I find Romanticism aesthetically compelling, expecting nature to reflect my inner self feels a bit arrogant, doesn’t it? Plus, we know that this idealization has been harnessed politically, like when Nazi Germany co-opted the natural space for a ‘pure’ national identity linked to ancient forest myths (we should also mention that the Nazi government passed some of the first nature conservation laws). We all know how it ended.

Another common idealization is the idea of Mother Nature: a feminine, nurturing, motherly being. Well, let’s talk about that. In my view, nature is a queer body (and mothers are not always ‘motherly’). The idea of a feminine, nurturing, motherly nature can be limiting and normative, for nature, like non-male bodies, can thus be controlled. When these bodies resist or deviate from norms, they are often labelled as ‘bad’ or ‘degenerate’ and all the horrible things we unfortunately still hear today.

In the arts, nature is frequently portrayed as a space of coexistence, which is a powerful narrative but overlooks essential aspects like conflict, pain, and death. In my view, engaging with these complexities is crucial for developing new narratives that move beyond the idea of nature as something to be controlled. By addressing frictional elements, we can explore more generative ways of being together, which is why I advocate against idealizing nature.

Wildfires are associated with destruction, human despair, biodiversity loss, economic damages, etc. Your work reminds us that wildfires also fulfil an important ecological role. They are part of the life cycle. This is so counterintuitive for most of us in the West. Can you tell us a few words about that? About the role that wildfires can play in life cycles?

There is something about art that I treasure: when I make it, I always learn a lot. It was the case for this project too.

There is often the idea that wildfires are dangerous and destructive and therefore must be prevented. Instead, fire is an ecological phenomenon with its specific complexity, neither bad nor good per se. Ecosystems and humans have historically co-evolved also with fires, in different ways across the globe. What makes wildfire dangerous, however, is when the local ecosystem or this co-evolution is unbalanced. Extreme events reveal the vulnerability of the co-evolution of ecosystems and humans.

In the last decades, eco-disruption has altered the so-called fire regimes – the fire behaviour and patterns. You now have wildfires that ignite during unusual seasons, become violent because of extended droughts, or spread fast because of the proliferation of certain plants, like what happened in Portugal in 2017. There are more ‘extreme wildfire events’.

The historical relationships between human communities, ecosystems, and fire are upset. For example, a simple rule used to be that areas near villages would be kept clear of wood so that fires wouldn’t reach the houses. But if managing the woods is no longer part of the local economy, woods grow back and, in case of fire, flames may reach the houses. Or take monocultures of species that are economically lucrative but prone to fire: the lack of biodiversity allows the fire to gain speed, sometimes with tragic effects.

Margherita Pevere, Lament, 2024. Performance and installation. Photo: Romane Iskaria

Margherita Pevere, Lament, 2024. Performance and installation. Photo: Romane Iskaria

The setting for your performance at iMAL in Brussels was striking: very white, with delicate glass sculptures. It looks peaceful. Yet, Laments deals with phenomena that we see as dark, brutal, frightening and powerful. Why did you create such a luminous environment for the performance?

Lament belongs to an ongoing series that deals with death as an ecology, beyond the life/death binary. The series includes installations, performances, objects, and writing. Materially, in Lament I manipulate matters that come from large wildfires – burnt soil, exploded tree barks, so-called ‘fire moss’. Aesthetically, I play with high dynamics and striking contrasts to open up an adequate emotional space. The setting transforms over the course of the performance: as I crawl and slide on stage, I also smear soil and charcoal powder around. At the start of the performance, the setting is luminous and immaculate. At the end, it is violent and expressionist.

The strong dynamics of the set, music, choreography, and materials allow me and the audience to explore a range of emotions, in particular with regard to death and eco-grief. Death is something that requires attention and a compassionate engagement. People mostly do not want to talk about death. It is something that always arrives as a shock even though we know that we will all die. Our culture avoids talking about it. Death is still surrounded by taboos and dominated by normativities. The immaculate initial setting and the range of tones and intensities are an invitation to enter a dimension where it is possible to address all those things.

In Brussels, you did one performance, but Lament remained on view for several weeks as an installation. Can you tell us something about the installation of the work? How do you infuse meaning and emotion in an installation in the absence of the performance?

Lament is a death-bed: it remains on view after ‘the event’ takes place. Moss and soil microflora will grow during the time of the exhibition, manifesting more life and death entanglements.

I designed the installation as a shape-shifter, so that it can be exhibited full scale as you saw at IMAL, host the performance and remain on view. Or it can be presented in a reduced shape with a smaller number of glass sculptures, for smaller venues.

Margherita Pevere, Lament, 2024. Performance and installation. Photo: Romane Iskaria

Margherita Pevere, Lament, 2024. Performance and installation. Photo: Romane Iskaria

In the performance, you incarnate a tentacular creature of the soil. That is another element of Lament that surprised me. When i think of wildfire, i think about everything that is above the ground: the forest, the air, the houses, etc. Never what is underneath the fire. Why do you think it was important to look at the soil too?

The answer is the same as before. In general, when people think of fire, they think of this spectacularity, the outrageous flames, the air you can’t breathe, the heat…. But only a few think about soil. Yet, wildfires have complex effects on soil. That’s why, during the research phase, I worked with Dr Diana Vieira, an environmental engineer who specialises in soil and wildfires.

The fire starts at ground level and then it goes up. If it reaches tree tops, it is usually already beyond control. It burns what is above ground, but it also goes into the ground in ways that depend on many factors, such as slope inclinations or how much dry material is on the ground. It can also burn into the roots of the trees. During preliminary research I visited burnt woods outside Berlin. It’s mostly pine monoculture. Certain tree logs burnt deep into the ground and I could stretch half of my arm into the hole.

The soil is affected in terms of seed bank, erosion, chemistry, etc. Charcoal and ash are fertilising in certain amounts, but become toxic when the concentration is too high. Only certain species of plants can grow on that ground. Burnt soil can be so dry to repel water… and rain after a fire can wash away soil and cause erosion. Thus, the recovery of a burnt ecosystem is an interplay of many aspects. Depending on how healthy the environment is, the recovery is more or less slow. Another decisive factor is how much time passes between two fire events: two years is too little for an environment to recover.

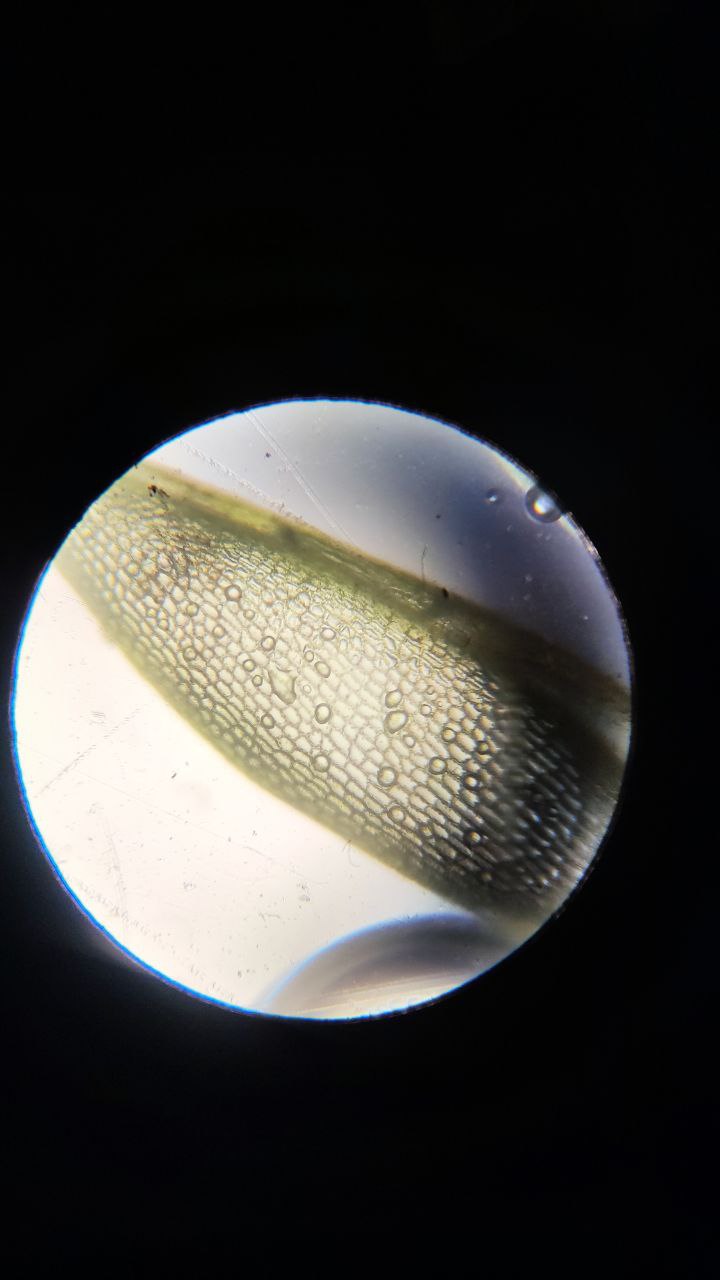

Moss Funaria hygrometrica on a burnt log. Photo courtesy of Margherita Pevere

Funaria hygrometrica through the microscope. Photo courtesy of Margherita Pevere

I’m also curious about the content of the glass sculptures: soil microbes, charcoal and moss. Where do they come from? How do they evolve over the course of the exhibition?

Yes, the small hanging sculptures (a hundred of them!) contain burnt soil, charcoal, microbial communities, and moss. But I need to do a small digression here.

As you know, fieldwork is a fundamental part of my practice (be it in a lab, or in the wild, it all counts as fieldwork for me). For Lament, I conducted fieldwork in Carso / Karst plateau, an area on the border between Italy and Slovenia that was affected by large wildfires in 2022. I know the ecosystem quite well: it is close to Trieste, where I did my studies and I spent many days and nights there. I did fieldwork first one year after the fire in the summer with my sister, and then one and a half years in the winter with musician Ivan Penov. He did field recording while I collected samples.

Do you know the poet Ungaretti?

No.

Miserable battles took place in Carso during WWI, and Ungaretti wrote some iconic hermetic poems as a young soldier stationed there. Carso is a place of strong contrasts and historically shifting borders: once under the Austrian Empire, then traversed by the Iron Curtain, now the permeable EU border between Italy and Slovenia. Recently, Italian Prime Minister Meloni reinstalled police patrols against migrants. … Sorry for the detour! These historical shifts made me reflect on ecology and human-made borders.

Carso is a place of white rocks and red soil. It has Mediterranean vegetation and there is a certain shrub species that becomes completely red in the fall. And then, the Adriatic nearby. It all makes for a striking colour and smell palette. After the fire, black burnt matter was dominating. On the floor during the performance there is a heap of red soil from Carso. Next to it, there is a pile of the same soil but burnt and it is completely black.

Wildfire can create ‘extreme’ conditions, to which few species adapt. During the winter round of fieldwork I was stunned to see that everything was black except for large patches of moss, bright green. There are so-called “fire mosses” that can grow on charcoal – and exploit the lack of competition, for such substrate is inhospitable to other species. And this feeds back into the recovery. When it rains, moss protects burnt, naked soil from erosion and keeps moisture.

I wanted to understand the role of moss in this recovery phase and did some tests with the soil samples I collected. Its strong alkalinity is inhospitable for many organisms. From the conversations with Diana Viera, I learned how mulching is employed after wildfires to support recovery, both against erosion and for bioremediation. So I had the idea to use moss for bioremediation. I’ve collected moss spores and inoculated my soil samples. I am currently running experiments in my studio. It’s a slow process – more-than-human temporalities! This is one of the processes that happen in the glass sculptures in the installation.

Margherita Pevere, Lament. Performance and installation. Photo: Romane Iskaria

Were you looking for specific samples or did you collect randomly?

There was a plan, upon which to improvise. As I said earlier, I am familiar with the area and built upon this. I was in conversation with Diana Vieira and the group from the Copernicus satellite fire monitoring programme at JRC. The database EFFIS is publicly accessible. It shows with precision where active fires are, but also allows you to rewind and look at fires from the past. I used the EFFIS database to study the dynamics of the 2022 wildfires.

Ivan and I connected with people living in the small municipalities around the fire area. They have precise knowledge of their environment, and this allowed us to bridge satellite data and local knowledge. Based on this, we identified a route and observation and sampling spots. I focused on soil and burnt, ‘dead’ biomatter. Ivan did field recordings.

Ivan Penov performing during Lament, 2024. Photo: Romane Iskaria

You worked with musician Ivan Penov. During the performance, he plays a composition for prepared cello and field recordings written especially for Lament. What was the brief you gave him to compose the musical accompaniment of the performance? How does his cello and the live electronics translate or add to Lament’s experience?

Ivan Penov is a musician and artist whom I’ve known since our Master’s in Trieste. His work often combines “physical” sounds with electronics, which he did also in Lament with cello and field recordings. We’ve worked a lot together over the years. And we know each other’s demons. He has an incredible musical intelligence.

When I invited him to join Lament and I explained my intuition behind the work, he had the idea of working with the cello. Ivan has classical training as a cellist, but as a young adult had to quit because of health reasons. He hasn’t played cello since then. For him, this piece was a way to deal with his grief as a musician and come to terms with the instrument again.

His field recordings in Carso explored the apparent ‘acoustic void’ that is left after a fire. There is no rustling of the leaves, no birds chirping, no leaves on the ground, etc. He then started recording the sound of burnt wood, gently using the cello bow on burnt branches. It turns out that burnt wood has very particular resonances and acoustic qualities that remind one of cries or resonating voices.

For the performance, he plays the cello for almost an hour, quite a long time for such a physical instrument. There was an element of exhaustion in his performance which I think added to the piece. He wrote a score for cello and live electronics, but left space for improvisation.

For both of us, it was important to bring the audience into a state where certain emotions can come out. It’s not just about sharing scientific knowledge about wildfires or technical prowess. We wanted to create a piece that speaks to people’s emotions. And indeed there were people at the premiere who cried.

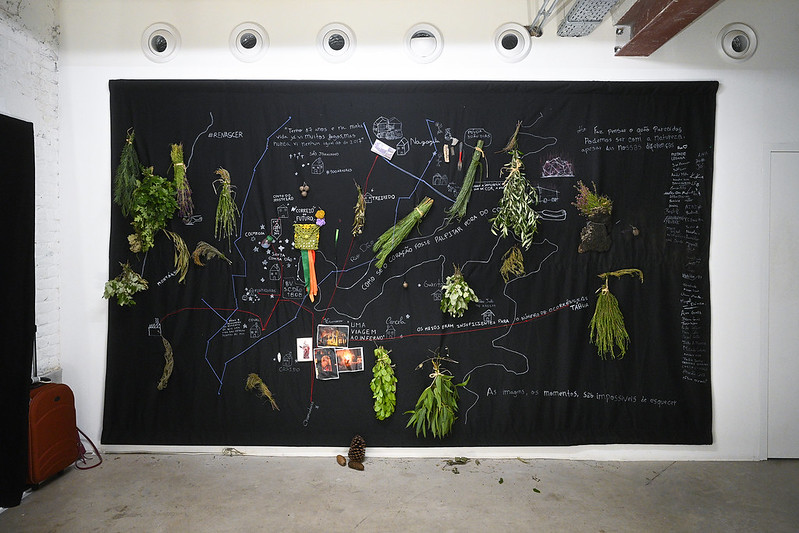

Lament: Resilient scars map by Margherita Pevere, Céline Charveriat and citizens of Santa Comba Dão. Photo: Romane Iskaria

Lament: Resilient scars map by Margherita Pevere, Céline Charveriat and citizens of Santa Comba Dão. Photo: Romane Iskaria

At the iMAL NaturArchy exhibition in Brussels, there was a huge wall that recorded the community engagement programme with the people in Santa Comba Dão, Portugal. How did the discussions and workshop with the community influence the final work?

One of my allies in the project is Céline Charveriat, an environmentalist and policy expert with a long experience in human rights. Currently, she is working on a ‘caring’ society and ideas for a future, starting from the awareness that future society and politics will be shaped by environmental damages.

Our idea was to engage with a community that had experienced extreme wildfires using a “sensory mapping”, which is a method to map the space not only based on measurements or geographical parameters, but rather on senses, emotions and memories. We teamed up with researchers of the University of Lisbon, CoLAB ForestWISE and FIRE-RES. They connected us with the municipality of Santa Comba Dão that was affected by the fire in 2017. In one day, the fire burnt 300,000 hectares, spreading over a distance of 60 km.

The local firefighters hosted us at their headquarters. The firefighters, local environmental engineers and the psychologist of the municipality accompanied us in meetings with citizens, students, women leaders, shop owners, elderly people and other members of the community. The whole process was based on dialogue and listening, visiting places and listening to people’s stories.

At the firefighters headquarters, we had a big canvas, drawing on a strategy I used in previous works. Here, we used simple materials like wool and pencils to draw a map of the village and the river along the satellite image of the so-called “fire scar”, which is the scar left by the wildfire on the territory. Then we drew and stitched images onto it, added objects found in the fire, and branches of local plants. There is even a purse made of crochet that contains messages for the future. It is an ‘emotional scar map’: scar map is a technical term, but we added emotional and subjective layers of the community’s experience. The work was a way to make space for healing, for grief, but also for hope and resilience.

For this part of the project, it was crucial to work together with researchers who know the community and the place. The local psychologist, for example, could guide and maintain all our exchanges in a safe space also when more delicate memories surfaced. It was an extremely meaningful collaboration, I am thankful for it.

The Emotional Scar Map was exhibited in iMAL and the Santa Comba Dão crew joined for a talk and a panel at the European Commission. After the exhibition, the canvas returned to the community so they can use it for future projects. Céline and I are also publishing a ‘toolkit’ of our method that can be used by activist and communities to deal with trauma in a generative manner.

Thank you Margherita!

Also by Margherita Pevere: Semina Aeternitatis: can you inscribe human nostalgia onto foreign DNA?.