“This book is a reminder of the world as it is, not the world of exaggerated claims or, even worse, the imaginary world of indefensible fantasies,” writes scientist and policy analyst Vaclav Smil in Invention and Innovation. A Brief History of Hype and Failure, an MIT Press publication.

“This book is a reminder of the world as it is, not the world of exaggerated claims or, even worse, the imaginary world of indefensible fantasies,” writes scientist and policy analyst Vaclav Smil in Invention and Innovation. A Brief History of Hype and Failure, an MIT Press publication.

The book looks at the fate of inventions of the past 150 years in order to have us consider the promises surrounding our techno-enabled future with caution, if not with a healthy dose of scepticism. Disappointments, failings and mistakes that occurred in the past are likely to be repeated in the future, Smil believes.

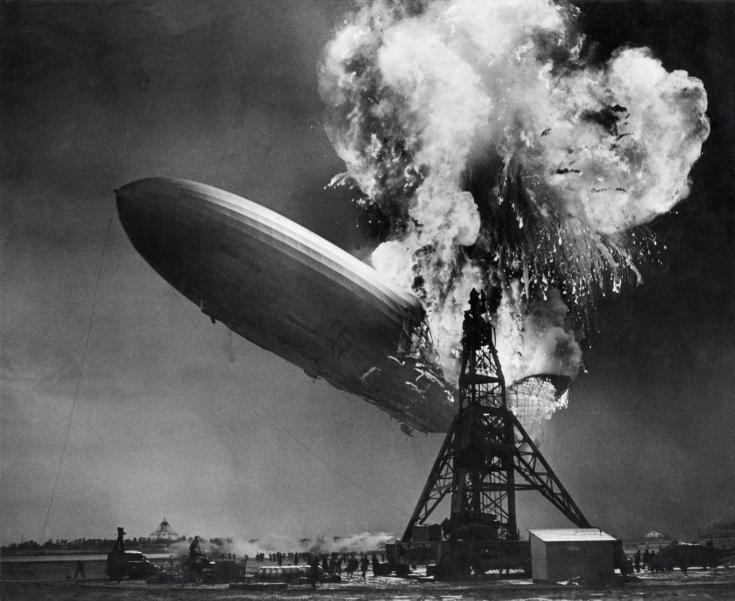

The scientist explains how past inventions that solved a critical problem and were commercialised on a global scale turned out to be so harmful to both humans and the environment that they were eventually banned. Perfect cases in point: DDT and tetraethyl lead in gasoline. Another category of inventions analysed in the book are the ones that never gained the domination they aspired to. Airships for affordable long-distance air transport and supersonic aircraft for speedy intercontinental trips are examples of disappointing inventions. That is where I learnt how exhausting trans- or intercontinental travels were in the early 20th century: it took three stops and more than fifteen hours to fly from New York to Los Angeles, and you’d need eight days and twenty-two layovers for the London-Singapore link.

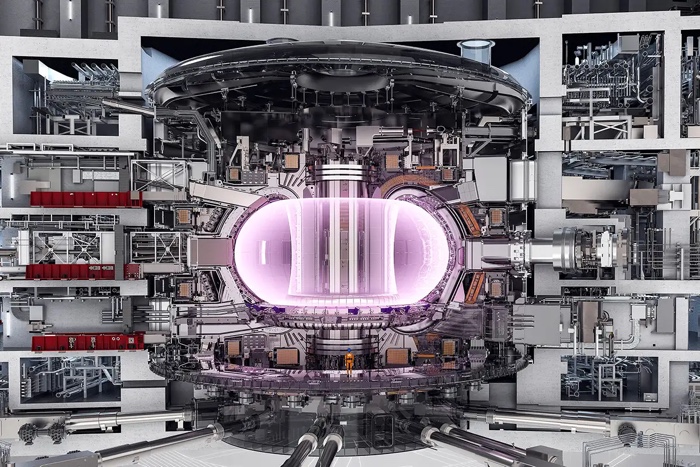

The ITER fusion reactor will contain the world’s largest magnet, which stands vertically in the centre of this illustration. Image: ITER, via

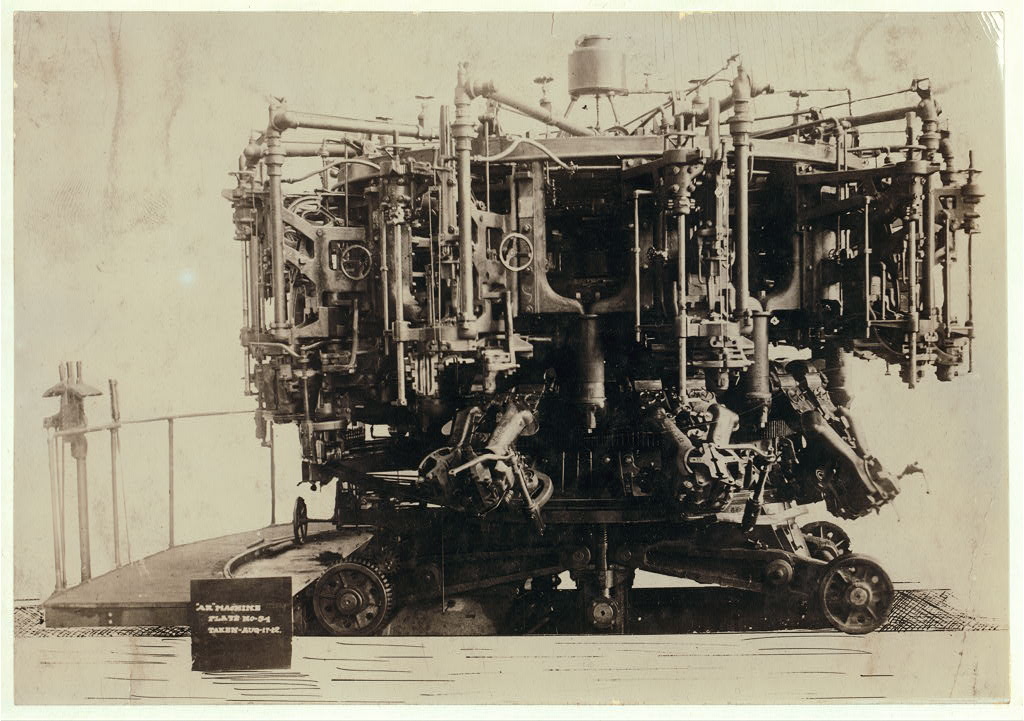

Michael Joseph Owens, Ten Arm Owens Automatic Bottle Machine, c. 1913. Photo by Lewis Hine

And then there are the inventions we are still waiting for, such as the ever-elusive cure for cancer or the less-discussed nitrogen-fixing cereal plants. If wheat, rice, corn and sorghum could act as legumes and secure most of their nitrogen requirements by symbiosis with bacteria rather than needing heavy doses of synthetic fertilisers, we would not only increase the global grain harvests but also be able to save energy and reduce drastically environmental pollution.

The Zeppelin LZ 129 Hindenburg on fire at the mooring mast of Lakehurst (United States of America) 6 May 1937. Photo: Sam Shere

Dragon Dream ML866 and Tustin Hangar, 2013. Image: Parkhannah

USS Nautilus (SSN-571) entering New York harbour following Operation Sunshine, 1958. Photo: U.S. Navy photo courtesy of the U.S. Navy Arctic Submarine Laboratory

The most interesting part of the book is the final one, where Smil denounces the inflated rhetoric that is often accompanying the techno-scientific “solutions” to every technical, environmental or social problem, no matter how vast and complex. News media play a non-negligible part in this cult of the technofix, by shunning nuances, uncritically relaying false promises and describing new inventions as “around the corner”, “disruptive” or “transformative”.

Analysing the myth of ever-faster innovations, the author explains that it is based on the mistaken impression that the rapid exponential advances of solid-state electronics can be applied to nearly all other aspects of our lives: from crop yields to efficiency gains in energy uses, from transportation speeds to gains in healthy longevity. Even AI, which efficiency seems to be growing by leaps and bounds, still hasn’t delivered diagnoses in every medical area, autonomous weapons on all battlefields and autonomous cars in our streets. That is because modern discourse is generally averse to engaging with uncontrollable complexities and unpredictable outcomes.

Perhaps more importantly, the book is also about the importance of getting our priorities right. We’re not going to stop inventing new materials, products, infrastructures and procedures, the author argues. We can’t always control failures stemming from lack of experience, hidden (on purpose or not) externalities, sheer human biases and unanticipated challenges either. We could, however, agree on “the most desirable items based on the two overriding needs: to improve the fundamentals required for a dignified life of the world’s population, and to do so without excessive impacts on the biosphere.” Of course, it is unlikely that a gadget or potion is going to help us reach that goal tomorrow. And that’s the problem with innovation that is literally “life-changing”: it is almost never as immediate and as sexy as we’ve been led to believe.

If I had to sum up my opinion about the book in a couple of lines it would be that the last section, the one about the unfulfilled promises and the misunderstanding surrounding innovations today, is by far the most compelling one. I only wish journalists, influencers, designers and engineers will read it too.

Related stories: Paleo-energy: a counter-history of energy, AI in the Wild. Sustainability in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, Disnovation, an inquiry into the mechanics and rhetoric of innovation, Can technology bring back long-lost nature?