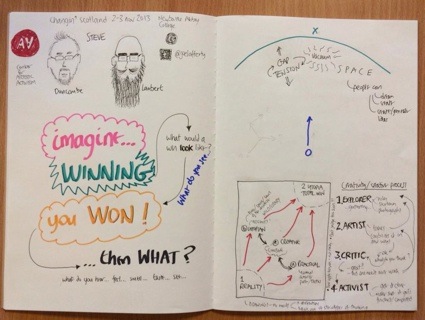

‘Imagining a win’. Photo: Flickr/Joe Lafferty (via)

Photos from Arts Action Academy at PSU’s Social Practice Arts program

The Center for Creative Activism is a place to explore, analyze, and strengthen connections between social activism and artistic practice. For the past few years, CAA’s founders Steve Lambert and Stephen Duncombe have been traveling around the U.S. (and increasingly Europe) to train grassroot activists to think more like artists and artists to think more like activists. The objective isn’t to replace traditional strategies with unbridled inventiveness but to use creativity as an additional tool that will help them gain more attention, make activism more approachable and that will, ultimately, make campaigns more effective.

Stephen is an Associate Professor of Media and Politics at New York University. He has received numerous recognitions and awards for his work as a teacher, organiser of activist groups and events. He widely publishes about culture and politics and is the author and editor of six books, including Dream: Re-Imagining Progressive Politics in an Age of Fantasy and the Cultural Resistance Reader. Duncombe is currently working on a book on the art of propaganda during the New Deal.

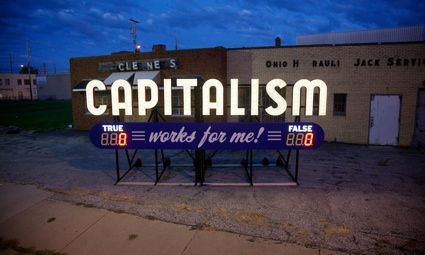

Steve Lambert, Capitalism Works for Me, True/False

Steve Lambert, Capitalism Works for Me, True/False

Steve is an artist and activist whose art aims to be relevant, engaging and visible outside the traditional gallery setting. His works are imbued with humour and subtle commentaries on current political and social issues.

The New York Times Special Edition, Capitalism Works For Me! True/False, Add-Art (a Firefox add-on that replaces advertising banners with art) and The Anti-Advertising Agency.

He is currently Assistant Professor of New Media at SUNY Purchase

I’ve never had the chance to attend any of their workshops but i’ve been following CCA’s tweets and reading their blog posts with great enthusiasm (i would particularly recommend having a look at An open letter to critics writing about political art, whether you are an art critic, a ‘socially-engaged’ artist or someone interested in political art.) From where i am standing, these two guys are among the most interesting, thought-provoking thinkers. I was eager to pick their brains….

Hi Steve and Stephen! In Europe at least, ‘socially-engaged’ exhibitions seem to have become very trendy. Is there any way an artist or curator can engage with meaningful artistic activism inside an art gallery or a museum?

Hi Steve and Stephen! In Europe at least, ‘socially-engaged’ exhibitions seem to have become very trendy. Is there any way an artist or curator can engage with meaningful artistic activism inside an art gallery or a museum?

This is a good question, but it can never be answered to any asker’s satisfaction.

Definitively saying something is or isn’t possible would be a mistake. With artistic activism, like anything in the realm of art, there are few concrete and lasting rules. This is why we have no specific “way” we are prescribing. We’re offering an articulated approach and a method for thinking through more effective and further reaching work.

Can you engage in meaningful artistic activism from inside an art institution? Sure. Anything is possible. It depends on the goals of the work. Are you planning the violent overthrow of the government? Because creating an exhibit in a museum is probably not the smartest step in reaching that goal. Are you “interested in attempting to re-examine the notions of the institutions role in blah blah blah” then yeah, a museum or a gallery is a great place to start.

Whether or not something is meaningful or effective has far more to do with the artist(s) intention. The forms this work can take are so open that they present few limitations to efficacy – you have so many choices. The trick is keeping your focus on impacting power through culture. In some cases that path may lead you through a museum, in others not.

If the artists intention and goal does lead them to a gallery or through a museum, they need to be aware of the context of their practice. Galleries and art museums are, by and large, set up to display works of art that are then looked at or watched by others. This encourages a social relationship of spectatorship, with all its attendant political ramifications. It also can tends to “reify,” politics be it social problems or social struggles. In these cases politics becomes an object for contemplation, or – perversely – appreciation, rather than action. As we like to say, political art is not necessarily art about politics, but art that acts politically in the world.

This does not mean that one should avoid art institutions, only that these institutions – like all settings – have their own dynamics and to be aware of and work with, or against, and work through.

The tragedy here is that a majority of the shortcomings of this work are not put in place by institutions attempting to support the work, but by the artists themselves in underestimating their ability, their role in culture, and not fully leveraging their strengths. Crudely, we could say that many artists are plagued by deep seated self-esteem issues that result in us aiming too low. We simply feel that we can’t have a great impact outside of the small and insulated worlds of art, so we don’t engage on a larger terrain.

This is not to say that institutional support, or lack of it, is not an issue. There is a chicken-or-egg problem here in that the training provided to artists and many of the established ways they are supported through the market and states are profoundly disempowering to artists. The power artists have in shifting culture is rarely acknowledged and popular myths about us as starving, insane, misunderstood outcasts are deeply rooted. In subtle ways these institutions can perpetuate disempowerment and support these myths.

That said, the recent uptick in support for this kind of work is a good thing in many ways. It acknowledges that art is not sequestered to traditional media and sacred institutions, and a recognition that art has tremendous power when it’s not decoration for the wealthy or academic navel gazing. And institutions can shift, change, and grow, so who knows what could happen.

This is a very long way of saying we can’t answer your question, other than to say that if we are serious about using art, culture and creativity to change the world then no setting should be off limits.

One of the projects run by the CAA is the School for Creative Activism, a training program for grassroots activists. Could you tell us about those workshop? What can activists expect from them?

One of the projects run by the CAA is the School for Creative Activism, a training program for grassroots activists. Could you tell us about those workshop? What can activists expect from them?

The School for Creative Activism is a two and a half day weekend workshop. It starts on a Friday evening at a modest retreat center we’ll find just outside whatever city we’re working in. On Friday we give an overview of what artistic activism is and isn’t and cover contemporary examples. Saturday we go through the history of this work – usually going back 2000 years or more with some big gaps along the way. The rest of the day is a mix of lecture, discussion, and activities around cultural, cognitive, and mass communication theory. Sunday is hands-on practice where we put all we’ve learned into play on a sample campaign.

We’re both professors and teachers. Duncombe has a doctorate in sociology and has extensive activist roots and Lambert brings his expertise in communications and fine art. We take all this information, condense it, and make it relevant and useful for working activists. We also get a few artists in the room to add perspective.

Over the past three years we have trained activists working on school desegregation in Mebane NC, prison reform in Houston TX, state budgets in Austin TX, immigration justice in San Antonio TX, tax fairness in Boston MA, and police surveillance of Muslims in New York City. We’ve worked with faith-based organizers in rural Connecticut and Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans in Chicago IL. We just finished a weekend with The Portland State University Social Practice Arts program. Overseas we’ve trained East African health activists in Nairobi and Scottish democracy advocates outside of Glasgow. In March of 2014 we are scheduled to work with health care activists in Skopje, Macedonia.

Because of the wildly different geographic and social makeup of these groups, our curriculum really has to work as a framework that can be adapted locally. You can’t drop-in to Kenya or Texas or Scotland and use a one-size-fits-all model. Culture is the resource, the raw material, we work with and culture is local. We can’t tell people what will work in their area and with the populations they want to organize, they need to tell us what the dominant signs, symbols and stories are, what media outlets they have access to and what creative resources they can muster. This is what makes this work so exciting for us: the activists and artist we work with are the experts in their cultural terrain so we are forever learning new things.

Creativity taps into an expertise that many people possess, but don’t think of applying to the “serious business” of politics. Even if most people don’t think of themselves as “artists,” they don’t compose symphonies or paint majestic landscapes, they sing at churches, rap with friend on a street corner, upload videos to YouTube, assemble scrapbooks, of even just know how to throw a kicking party. “I’m not political,” is a phrase one hears often; it’s a rare person, however, that doesn’t identify with some form of culture and creativity. Culture lowers barriers to entry. As something already embraced, it has the capacity to act as an access point which organizers can use to approach and engage people otherwise alienated from typical civic activity and community organization. In fact, cultural creativity is often the possession of those – youth, the poor, people of color – that are most marginalized from formal spheres of politics, law, and education.

How can art help them organize more successful campaigns?

We have a motto at the CAA: “The first rule of guerilla warfare is to know your terrain and use it to your advantage.” The political topography of today is one of signs and symbols, stories and spectacles. And for all the limitations of traditional artistic training, it is artists who are the best adapted to working on this political landscape. In order to be a good activist you need to learn to think like an artist.

One of the problems with much of activist work is that it’s based in a faulty understanding of political motivation. We do an exercise at the beginning of every training: We ask participants to introduce themselves and give a brief account of what they are working on and tell us about the moment they became politicized. After everyone is done we go back and point out that no one mentioned they became interested in affecting change in the world through signing a petition, reading a factsheet, giving a donation, or even going to a march or rally. Yet that is exactly these means that activists use to approach others to have them “get involved.” The politicization experiences people do describe in this exercise are vivid, visceral, and emotional experiences. Dreams, fantasies, emotions. Moments felt rather than just thought. Affective experiences. Well, this is the domain of art.

Unfortunately there’s a pressure to do things that are sure to work. With activists especially, the stakes are high. When we’re working with healthcare advocates in Eastern Africa, if they take a risk that doesn’t work people may literally die. We don’t ever advise that people should abandon the standard tactics of activism: the marches, the rallies, the petitions, the knocking on doors and lobbying politicians. What we are suggesting is that artistic activism provides another tool for the activist’s tool box. But as any carpenter can tell you, once you have a new tool it opens up possibilities of new jobs to work on.

Members of Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) staged military operations in the United States to give fellow Americans a glimpse of the day-to-day realities of the war (Photo: IndyBay/Ian Paul)

Members of Iraq Veterans Against the War (IVAW) staged military operations in the United States to give fellow Americans a glimpse of the day-to-day realities of the war (Photo: IndyBay/Ian Paul)

Do you have a couple of examples of workshops that lead to particularly fruitful actions?

We were sitting in a restaurant a few weeks ago getting lunch and one of our former workshop attendees happened to be at another table. We asked what he was working on, and he mentioned he was organizing fast food workers. He then told us. “Oh you know, we’re using a lot of what we talked about in the workshop in the Fast Food Workers Strike.” What impressed us was two things: one, that some of what we were teaching had some impact on this amazing, high-profile campaign that we had admired from afar; and two, that we would have never known without this chance meeting.

If we’ve been successful, when we’re done with the workshop the participants have a feeling of ownership over the method. When they put it to use they don’t often consciously think “Now we’re using artistic activism!” Instead they find ideas and methods which resonate and feel true, so they use them. Which is exactly as it should be – part of an overall skill set that activists can tap into and employ when and where it’s useful.

It reminds us of what Lao Tzu once wrote:

As for the best leaders, the people do not notice their existence…. But when the best leaders’ work is done, the people say ‘we did it ourselves’

We think the same is true for teachers too.

Reverend Billy leading mass exorcism in Tate Modern Turbine Hall over BP sponsorship

Reverend Billy leading mass exorcism in Tate Modern Turbine Hall over BP sponsorship

Which brings me to the question you ask to the artists you interview: “How do you know if it works?” What are the criteria that help you establish whether a work has had any social or political impact?

This is what everyone, including us, wants to know. What is the formula? Is there a checklist to run through? Are there singular and universal right answers to this? And of course, there is not.

While it’s helpful to have measureable objectives – a change that is visible – often it’s similar to answering the question “what makes a good artwork?” because there’s part of artistic activism that has no objective standard and the most important outcomes may be immeasurable.

The first question to ask is “What was the artist trying to do?” If an artist set out to be successful in the art market, there’s no real sense in being critical of their lack of political impact because that wasn’t their intention. Better questions are, did they succeed in what they set out to do? And were those goals ambitious enough?

For example, we often hear political artists say things like “I’m interested in raising awareness about issues around immigration.” This statement is so vague it could also serve as a mission statement for a Nazi propaganda office. Consciousness raising is only useful as a means directed towards something larger. Not addressing a specific, distant goal is a strategic error. Unfortunately merely political content is often what passes for political art, while it has little political impact. If the artist were to be more ambitious and more specific, “I will create a more accepting culture around immigration through my art work” they’d probably be more successful because they’d have a clearer idea of what they were trying to do.

When we work with artists directly, as we do through our Arts Action Academy, we really push artists to think about what they want to have happen through their work. Many will initially say something like “I want to raise awareness of X” or “I want to start a discussion about Y.” Fine and good. But then we ask, if you succeed in raising awareness or starting a conversation, what then do you want to have happen as a result? Most of the times there are grander motivations underlying these tame aspirations. It often turns out that the artist doesn’t just want to raise awareness or start a conversation about immigration, they want that awareness or conversation to lead someplace: to help stop some particularly heinous law that punishes immigrants and open up the borders between people and nations. Being aware of this helps us sharpen our thinking about our art and its impact, and it also helps us determine whether we’ve done what we’ve set out to do.

This thought process also helps us think about creative work as a piece of a extensive campaign. An artwork that raises awareness or starts a conversation is just one tactic; a tactic to be followed by others: perhaps art that aims to empower immigrant communities or embarrass right wing demagogues or pressure lawmakers. And all of this fitting together in a larger strategy aimed toward an ultimate goal of a more humane society. Without this greater strategic understanding there is a disconnect between the action and the, often unacknowledged, desired result. This tends to lead to either delusion: “My piece will change everything!” or depression: “My piece changed nothing.” Both are debilitating.

We could go on addressing “what works, and how do we know it does?” forever because we are obsessed with this topic, but of your readers are curious, we’ve written more in our Open Letter to Critics on Writing About Political Art following the 2012 Creative Time Summit in NYC, and in a short essay, Activist Art: Does it Work? we wrote for the Dutch journal Open.

Oh! I loved that Open Letter, I found it so useful.

Have artists and activists the same definition of what constitutes a successful action?

No. That’s both the problem and the promise of artistic activism.

Activism tends to be very instrumental: the goal is to change power relationships and you have clear objectives that result in demonstrable change in the “real world.”

Art tends to be expressive, interested in making something new and unique. It’s a practice concerned with shifting perspectives and creating spaces for this to happen, what Jacques Rancière calls the “redistribution of the sensible.” With art there are indirect results, or perhaps no instrumental result at all. And most art is experienced outside of the “real world,” in special refuges like museums and galleries.

These are often at cross purposes to one another. They are often hard to reconcile. It’s not easy! It is an art. But when you can do it, it makes for powerful activism (and profound art)

I’m also very curious about the Art Action Academy, a workshop to help socially engaged artists become more politically efficacious. What are the skills necessary for political action that no art academy ever teaches you?

Well, schools could teach these things, they just don’t. Programs have popped up and they have begun to try. But activism and organizing are real skills – just like painting or dramaturgy – and there are lessons to be learned. Lessons like:

Thinking about audience, particularly audiences unlike yourself

Long term collaboration with groups and institutions

History and theory of social movements

Processes of behavioral change past “awareness.”

Research in kindred fields like sociology, psychology, cognition science, and social marketing

Power mapping: knowing who holds what power to effect change

Campaign planning with tactics, strategy, objectives, and goals.

Because we believe in the democratic ideal of the every-day active citizen we tend to downplay the fact that activism is a demanding practice that requires particular skills and substantial practice. Ideally, we will all one day have those skills and practice, and we will live in a world where everyone is an activist (as well as an artist) but until then it is necessary to learn – and to teach.

Rosa Parks sits in the front of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956 after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled segregation illegal on the city’s bus system. Behind Parks is Nicholas C. Chriss, a UPI reporter covering the event

Rosa Parks sits in the front of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956 after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled segregation illegal on the city’s bus system. Behind Parks is Nicholas C. Chriss, a UPI reporter covering the event

Now say i’m an artist and i’m interested in political action but i cannot afford to travel to the U.S. to attend one of your workshops, where should i start? Do you have any book, video or other tool to recommend?

We both hold down paying jobs as university professors so we can’t do as much, and go as many places, as we’d like. In recent years we’ve expanded our workshops out of the borders of the US to Europe and Africa and we plan to do more of this. That said, we’re only two people with limited time and resources so we can’t be everywhere and do everything we’d like. Recognizing our limitations we are working on a book that will take the research we’ve done and the lessons and exercises from our workshops and make them accessible to more people.

We also have resources for artistic activists on our website: a reading list of texts that we’ve found useful, and Actipedia.org, an open-access, user-generated database of global artistic activism case studies that we created with The Yes Men.

Are there any relevant yet overlooked issues you think activists and artists should approach today?

There’s plenty of relevant issues and we come across new ones all the time. Nearly all of them are overlooked in the grand scheme of things.

If you’re asking if there are topics we feel artists should be working on, we think it’s always best to pick whatever compels you the most. There’s always work to be done and if we tried to pick out what was most important, we’d probably be wrong anyway. We’re all in it together, so everyone needs to work their hardest on the things they care about most…and support one another

Do you have any plan of coming to Europe by any chance? I think we’d love to have the CAA here.

Do you have any plan of coming to Europe by any chance? I think we’d love to have the CAA here.

We were just in Scotland. This Spring we’ll be running a five day School for Creative Activism workshop in Macedonia working with health care activists, and it looks like we’ll be hosting Art Action Academies in Sweden and Russia too.

While our time is limited, we really enjoy meeting and working with activists and artists working on campaigns and in contexts that are new to us. It’s how we lean and grow too. If people are interested in bringing us to Europe – or elsewhere – they can always contact us trough the center at [email protected].

We’re definitely open to it.

And more generally what is next for the Center for Artistic Activism?

We’ll continue working with as many activists and artists as we can through our workshops while finishing our book so we can reach even more.

Thanks Stephen and Steve!

Check out also the video of the talk that Stephen Duncombe delivered in Copenhagen on January 23rd, 2013, for activists and NGO workers affiliated with Action Aid Denmark.