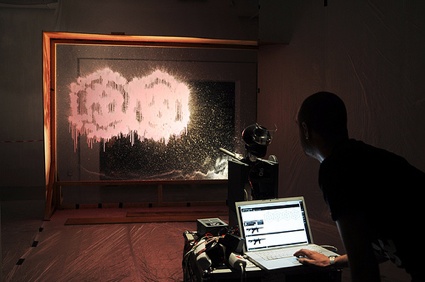

Benjamin Gaulon -aka RECYCLISM– is an artist, researcher and art college lecturer. And to be honest, when i see how much he manages to pack in each of his job descriptions, i’m starting to suspect that he benefits from more than 24 hours per day. I’ve read about his artistic activities ever since i’ve started blogging. Often both playful and critical, his projects involve printing messages on walls using a PaintBall Gun, collecting video streams from wireless surveillance cameras, turning your videos into animated GIFs, developing radio controlled cars that physically react to messages sent on Twitter, giving an architectural dimension to the 1970s game PONG, circuit-bending, hacking, deconstructing and re-purposing “obsolete” electronic devices.

Self-portrait – 2.4Ghz from Surveillance to Broadcast

Self-portrait – 2.4Ghz from Surveillance to Broadcast

Last year, Benjamin opened the Recyclism Hacklab, a shared studio space where people interested in physical computing, gaming, interactive and media installations, programming and more can find basic electronic tools,, storage for ongoing projects but also mentoring sessions for electronic, programming, conceptual support, etc.

The GAMERZ festival invited him to show his Printball graffiti robot and i took the opening of the exhibition as a heaven-sent opportunity to catch up with Benjamin Gaulon. After that we had an email conversation which, laborious little blogger that i am, i’m going to copy / paste below:

2.4Ghz from Surveillance to Broadcast

2.4Ghz from Surveillance to Broadcast

Hi Benjamin! Let’s start with one of your latest projects. The 2.4Ghz project uses an affordable and widely available wireless video receiver to hack into wireless surveillance cameras. Including the ones people use for private reason, to monitor their baby for example.

This project has 3 layers. One of them consists of placing the device in the street to reveal the presence of the cameras and to make obvious the fact that anyone can receive those signals, a fact most people don’t seem to be aware of. Can you tell us about this part of the project and how people react to it?

The 2.4GHz project actually started in 2008, however I have recently made new versions for two events: Hack the City at the Science Gallery (Dublin) and Mal au Pixel at La Gaîté Lyrique (Paris). This project started with an article about a mother receiving images from the NASA space station on her baby monitor, which got me wondering how this could even be possible. After some research I found out more about the 2.4GHz video signal and how open and easy it is to receive surveillance cameras and, in some cases, baby monitors. Once I found a receiver, with a built-in display, I decided to place the device in public spaces to reveal that signal, as a street art intervention, as you said, to expose the weakness of such system.

The reactions of people passing by are of indifference and more often surprise and enquiry. Most shop owners don’t seem to mind that much about the fact they are broadcasting what they are trying to look after. I guess the same way many people today share a lot of their life on Facebook. The concept of privacy has changed with the rise of social media and the wide spread of surveillance camera in public and private spaces. Very often, when I’m installing the devices, people passing by would stop and ask me what I’m doing, and this is partially what I’m looking for, a moment of dialog allowing me to explain the project and engage in a discussion about the matter outside galleries and festivals.

Last time in Paris, someone asked me if I was looking for water, which is not far from the truth as there is a bit that feeling when searching and finding surveillance camera signals. This is what brought me to organise workshops, so others could share that thrilling experience of searching and finding signals in cities.

2.4Ghz from Surveillance to Broadcast

2.4Ghz from Surveillance to Broadcast

Do you ask permission to broadcast the images you capture for example?

But also is there a ‘privacy’ law related to that? Is it legal to collect the footage as you do?

And when you organize a 2.4GHz Workshop, do you have to take some precautions? Warn the participants they might get into troubles?

I do not ask permission to display the signal, as part of the project is to show how easy it is to hack into those signals. Also, in some cases, it is impossible to know where the signal comes from (when a camera is inside a building for example). About the legal aspects, I haven’t really looked into the law of each country where I did this project to be honest. And I’m not the one broadcasting, I believe there are laws against that rather than receiving. I’m simply displaying a signal that’s out there. The same way someone on the street would be listening to the radio.

About the workshops, I only ask participants to take some ID with them, just in case they get stopped by the police and need to talk their way out, which never happened by the way. From past experiences with other projects in public space, like placing a dodgy looking, noise-making, electronic device on screens of Time Square (next to police forces), I never had any troubles.

L.S.D Sonic Graffiti (Testing @Time Square, New York)

‘Glitch’ and ‘corrupt’ are two of the keywords of your artistic practice. Your project sometimes attempt to disrupt technology, to make it stray from its usual function and aesthetics. What do you think is fascinating about a damaged image or device? To you personally but also why do you think people are so attracted to it (judging from the enthusiastic reaction that your projects often get)?

My Corrupt projects series came from an earlier project, started in 2001, called: digitalrecycling. It was an online, digital garbage, recycling centre. The website was an exploration of trash and ownership in the digital realm. From the website, users could upload unwanted files (digital trash) and, once sorted by file types, others could download them for later reuse / remix. This project was also a comment on how operating systems tends to mimic the physical world (desktop, files and folder and the trashcan). The idea came from the unfortunate experience of trashing a file by accident. After using a data recovery software, the recovered document ended up corrupted (glitched). I thought it was quite fascinating idea that, when you trash a document in a computer bin, it gets “corrupted” or “damaged” the same way if you pull a piece of paper from the bin after you trashed it by accident you get it back dirty (corrupted).

While I was busy with digital garbage, I looked into files corruption and how I could recreate the conditions of such glitch (and not fake it but actually damage the file). So I made the first of the Corrupt projects, in 2004: corrupt.processing (a Processing code allowing users to read and damage files on a binary level). This project was quickly followed by corrupt.online (the php version of that algorithm, allowing thousands of users over the years to glitch images from the website by altering jpeg images on a binary level). I’ve recently made a video of all the content uploaded and glitched on the website since 2005 (over 1h long and visible here). I like the idea that, from a large database of corrupted images, what emerges is a story, in a way, of the entire internet.

Glitch, as a concept and a term, became more popular recently with people starting theorising more about it, like Rosa Menkman with her Vernacular of File format and with the Gli.tc/h festival for example. I remember being quite influenced by an earlier text by Kim Cascone “The Aesthetic of failure” when I started exploring image corruption.

What I see in glitch, in relation to my practice, is a way to engage with a critical discourse toward technology, obsolescence and digital materiality.

When corrupting a digital image, you reveal its inner structure, in other words, you reveal the code behind an image. Each file format (or compression algorithm) have different outcomes when corrupted. On some level it is a way of revealing the materiality of a digital image on a very low level. For me it is also a way to engage with technology in ways that were not intended. And by doing so, moving away from being a passive user of tools made by others. When breaking a system I feel more in control over it. Even if glitches are unpredictable, which is part of the beauty of it.

Maybe, in failure, we find ourselves less distant from digital information, we can somehow relate to failure, as humans, since we are not, in anyway, perfect machines operating on code. But it’s hard for me to talk for others as I think if you ask what people see in glitch, each person will give you a different answer. I suppose part of the recent wide spread of glitch practices, is also a visual exploration of glitches on an aesthetical level (and often recycled by advertising).

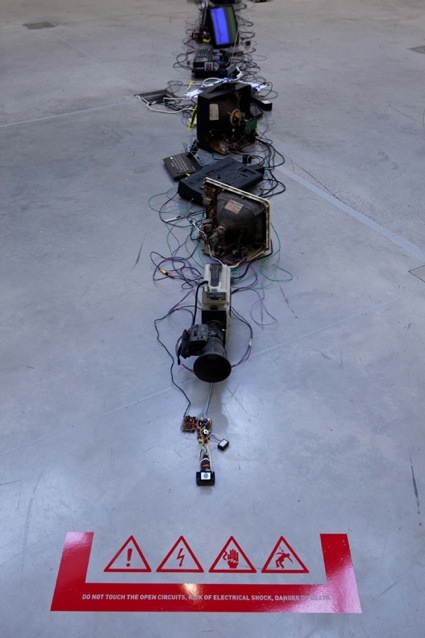

About “damaged” devices, well it is a whole different story. I’ve been researching the potential of electronic waste as a way to expose planned obsolescence for many years now. Among different projects dealing with hardware hacking, I’ve initiated a project called ReFunct Media in 2010, which is, in a way, a prolongation of the e-waste workshops I have been running since 2005.

Corrupt.desktop, Fnac, Aix en Provence

And is reversing the glitch something you pay attention to? i’m thinking in particular of Corrupt.desktop, an app you developed together with Martial Geoffre-Rouland to allow people to glitch, in real time, a computer’s desktop image at any Apple Store or Apple Retailer.

The project Corrupt.desktop is actually a derivative project of Corrupt.video (a software for real-time video glitch combined with a YouTube-like platform www.uglitch.com, allowing users to upload glitched videos from the software to the website). One of the features of Corrupt.video is the possibility of glitching your computer screen.

From this possibility, came the idea of making a separate software that would just do that, but with a twist since we renamed it “Safari” (using the Apple browser name and icon). Since then, I have being going to Apple stores (so far only 2, PC World in Dublin and la Fnac in Aix-en-Provence) to install the software on as many computers as possible, while recording the intervention on video. I see this type of intervention as Apple’s retailer hacking. I believe it is a humorous way of disrupting capitalism and an attempt to challenge Apple’s slick and shiny image. I’m also inviting people to take part in the project by doing the same actions where they live and sending me their recorded footage.

You’re at the origin of the e-waste workshops, which as they name suggest use e-waste as raw material to create interactive art projects. Could you give us a few examples of projects developed during these workshops?

The e-waste workshops have been going on since 2005 and hosted in different countries with a large variety of participants. I run those with Lourens Rozema (an electronic engineer based in the Netherlands). Our goal is not necessarily to have finished pieces (even if it’s better when it happens) but to get participants to see the potential in hacking e-waste and learn basics of electronic and programming in the process.

So to answer your question I can mention some projects. In the first session a group of participants made an interactive drawing machine using 2 scanners and a floppy disk controlled by microphones, allowing users to controlling the drawing machine by shouting at it. Drawing machine are often a good way to start and learn, we had few of those. Another one used an old printer combined with a webcam, users could draw on a long roll of paper, scanned by the webcam to generate sound (using computer vision). The most complete drawing machine was created by Charles Mazé and called the Rétrographe, using an old bulldozer toy, turned into a font making machine that he used in projects long after the workshop. Another, very low tech, interactive project (not directly recycling e-waste but still very good) is DanceKarpet, using cardboard and light bulbs power from car battery to make an interactive, very low resolution, interactive screen.

Sound making projects are also a regular way of reusing old electronic (as in circuit bending), or in some cases creating new instrument, by using old tape player heads and magnets, bended video games, making a sound controller from an old phone, a monkey head, etc…

e-waste 7.0

e-waste 7.0

What would you advise me to do with my own e-waste? How can i discard them responsibly?

Since we started those workshops, things got better, there are more (proper) recycling facilities in Europe (just make sure they do recycle the stuff and not simply ship the stuff to China, India or Africa). However I guess part of the point of our workshops is to say that recycling (dismantling for materials) is maybe not the only way. It comes with a cost in energy and chemicals used in the process, when in some cases, part or all of the so-called obsolete device could be reused / hacked into a new project or product. This way of thinking should be more widespread when it comes to making new devices. Making open-source hardware is a good start as it allows easier hacking in the future (if the documentation is clear and accessible). Circuit bending or hacking of recent electronic devices is also getting a lot harder than for older electronic. Parts are getting smaller, which makes this type of practices very hard (or impossible). This is really an issue that we see in the e-waste workshop when people bring too recent devices.

Physical Computing Master Class at the Hacklab

Physical Computing Master Class at the Hacklab

If i understand well, the e-waste workshops have given way to the Recyclism Hacklab, a permanent space offering workshops, mentoring sessions, support, etc. Who is the hacklab for? hackers? artists? professionals of IT technologies? Children? Un-usual suspects?

I guess anybody looking at learning and also sharing their skills about hardware hacking, e-waste recycling (and the usual Arduino, PureData, Processing,…). But more importantly people interested in Critical Making (a term coined by Matt Ratto). This idea of of Critical Making is also behind a publication coming up (led by Garnet Hertz), which regroups artists, designers, educators, theorists, makers from all over interested and engaged with this concept. I also believe hacklabs and hackerspaces have an important role to play in reshaping capitalism. The Recyclism Hacklab is my modest contribution to this topic.

The Recycling Entertainment System, at SonicActsX Amsterdam

The Recycling Entertainment System, at SonicActsX Amsterdam

I’m also quite curious about how this interest for recycling, re-purposing, re-using e-waste translates in the aesthetics of your various projects. Is this something that matters to you? Do you, for example, purposely attempt to create devices that look a bit vintage or second-hand?

Many of my projects are reusing vintage devices, like the RES (Recycling Entertainment System) that reuses 6 NES controllers, so the vintage looks is inherent to the technology I’m recycling / referencing in that case. With ReFunct Media I have invited other artists to collaborate on a large scale circuit-bending installation, where we purposely reuse obsolete/vintage devices (video games, ancient computers, turntables, tape players and so on) that we open up and hack together in a complex chain of interconnected devices. This project deals with the temporality of media and technological obsolescence, while revealing the process of its production by keeping every wire or circuit boards visible. Somehow, I see this type of projects as a practice-based media archaeology. I feel very close to the concept of Zombie Media (by Garnet Hertz / Jussi Parikka), part of this essay was included in the publication for ReFunct Media #2.

When it comes to aesthetic choices, I suppose, I try to make coherent propositions in relation to the piece of hardware I’m hacking. So the second-hand look is actually due to the second-hand devices I’m using. But I suppose there is also probably some part of nostalgia in hacking early video games considering I grew up in the 80s. For example with AbstracTris, when I turn a Gameboy screen into a lowtech generative pixel art piece, I can’t help but think of myself as a kid playing Tetris on the Gameboy for hours while making it. Or with Harddrivin’, a twitter controlled car racing installation, I have chosen to collaborate with an artist (Ivan Twohig) whose sculptural works refers to early days 3D polygonal modeling (considering that Hard Drivin’ was one of the first 3D polygonal driving environment).

While preparing this interview i found about Protonoir where you are selling some of your works, are you involved in this online shop?

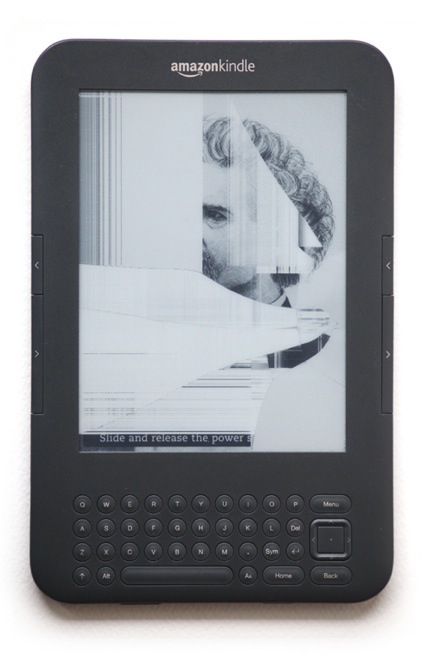

Well yes, directly. Ivan Twohig and I wanted to find other ways to distribute our works and we both had pieces we wanted to sell. Since none of us felt like adding a commercial side to our websites, we decided to set up this online store and invited other artists to join (people we know / works we like). We see this a bit as a museum or gallery shop, except we cut the middleman. So there is no fee or commission for artists featured. I wouldn’t say it has been a huge commercial success but it is more a practical thing when people ask about buying a project. We are open to works by other artists but we reserve ourselves the right to choose things we like and that we consider fit for the website. The website became also part of one of a recent project: KindleGlitched, a series of readymade glitched Kindles donated, found or bought on eBay that I laser etched with my signature, and sell (again), as an art piece, on Protonoir.com.

KindleGlitched

KindleGlitched

You’re French but you’ve been living and working in Dublin for a number of years. Why is this a good city for you?

Despite the current economical climate (and climate in general ;-), Ireland is a pretty good place for me. Dublin is small yet it’s a European capital. I’ve been here for nearly 7 years. I’m teaching at the National College of Art and Design in Media (in the Fine Art Media Department). I’ve been running (with Rachel O’Dwyer) an organisation called D.A.T.A since 2007 (Dublin Art and Technology Association, initially created by Jonah Brucker-Cohen). After starting in an artist led space, I’ve recently moved the Recyclism Hacklab to the CTVR building (The Telecommunications research centre of the Trinity College), which is another amazing opportunity.

ReFunct Media v1.0

ReFunct Media v1.0

The Printball. Photo : Luce Moreau – for M2F Créations

The Printball. Photo : Luce Moreau – for M2F Créations

Any upcoming projects/events/exhibitions you want to share with us?

The next stop is Chicago for the GLI.TC/H festival, where I’ll be a track leader focusing on “Hardware hacking and recycling strategies in an age of technological obsolescence”

Soon after, I’m very pleased to present, with the usual crew Karl Klomp, Gijs Gieskes and Tom Verbruggen and two new special guests Phillip Stearns and Pete Edwards, ReFunct Media #5 for the next Transmediale Festival in Berlin.

With D.A.T.A we are also discussing the next OpenHere festival (a four days festival that addresses social, technological and cultural issues surrounding the notion of the digital commons).

And hopefully find some time to make new work in between.

Thanks Benjamin!