James Auger is a research fellow within the Interaction Design department at the Royal College of Art in London.

James Auger is a research fellow within the Interaction Design department at the Royal College of Art in London.

He has been working together with Jimmy Loizeau since 2001. They were both students at RCA at the time and they came up with the much talked about Audio Tooth Implant. Their website consists of both joint and individual projects. “When collaborating we share all areas of development and realisation equally, we’re a bit like Rolls-Royce but without the Rolls (he was the business minded one),” says Auger. “We both work outside of the partnership (I’m at the RCA, Jimmy teaches at Goldsmiths) this work funds our own projects.”

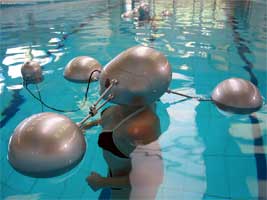

Between March 2002 and Jan 2005 he was a research associate at Media Lab Europe where he and Loizeau were exploring technology’s effect on human culture, behaviour and experience. That’s when i saw one of their works for the first time. In 2004, they were showing the Iso-Phone on Linz’ main platz, for the festival ars electronica. This extreme telecommunication concept blocks out peripheral sensory stimulation and distraction, allowing the wearer of the Iso-Phone helmet to focus fully on the phone call. The only sensory stimulus present is a two-way voice connection to another person using the same apparatus in another location.

What can i say? I found the idea both scary and appealing. So i kept an eye on what these two were doing. Got in touch with Auger when i heard that he would be showing several prototypes of Augmented Animals gear in Lausanne (they are at the MUDAC until February 17) and ended up asking him if he had time for an interview.

Auger-Loizeau recognizes “that for each placated consumer of technology there is an unsatisfied, complicated or strange one.” Does it mean that all your projects start with the encounter of an unsatisfied or complicated user? Any unsatisfactions and complications you’d like to work on in the near future?

Auger-Loizeau recognizes “that for each placated consumer of technology there is an unsatisfied, complicated or strange one.” Does it mean that all your projects start with the encounter of an unsatisfied or complicated user? Any unsatisfactions and complications you’d like to work on in the near future?

Actually this is an old statement that we are planning to replace in the near future, things have evolved a little since we wrote that. Certainly the statement remains at the core of our investigations.

Not all our projects start with an unsatisfied user but as a rather sweeping statement we’d say that all users are complicated having needs, desires and nuances that are not addressed by mainstream design practice. With this in mind our aim is to explore the role of technology and its manifestation in new and existing products and services. We’re sometimes inspired by words from the likes of Neil Postman, Marshall McLuhan, Jacques Ellul and Martin Heidegger but these can be a little inaccessible and remain within the confines of academia, we feel that the language of products has a much broader appeal and can therefore take the debate on technology to a wider public audience.

Our products provide an alta-vista on how we could interact with technology for better or for worse. They tread a fine line that tries to maintain a grip on reality whilst dealing with the complex social issues that result from an increasingly technologically mediated existence.

Current complications we’re working on; mourning in a technocratic age and an exploration into the hidden potential of the sense of smell. (more about this later).

From what I’ve heard and read, people seem to love the Augmented Animals project. A reason for that might be that consumers are getting pet-techno-crazy these days. You started working on the project in 2001. Since then, companies have launched a phone for dogs, a translator for dogs’ barkings, all kinds of interactive bowls, collars and toys for pets, etc. Do you think that the project is loosing some of its “strangeness” as time goes by?

Perhaps slightly cynical but I think that recently designers and

manufacturers have started to realise the untapped potential of the pet industry. Where their pets are concerned doting owners are willing to pay substantial sums for weird gadgetry that somehow enhances the “petness” of the animal. These products are for the benefit of the owner so therefore it’s easy to imagine how they come to marketable fruition.

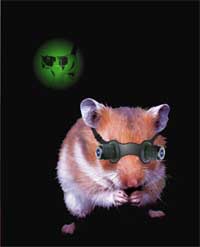

The products in the Augmented Animals series were all conceived with the animal’s wellbeing in mind. Some of the proposals such as the status enhancers (methods for turning vermin and pests into entertainers and celebrities to enhance chance of survival) by their very nature are also of benefit to humans therefore these could be confused with marketable products and as such are certainly are becoming less strange as time goes on. Concepts such as the Night Vision goggles for rodents remain to me, extremely odd. Although feasible hypothetically, who would pay for the development, manufacturing, distribution, fitting and maintenance?

The products in the Augmented Animals series were all conceived with the animal’s wellbeing in mind. Some of the proposals such as the status enhancers (methods for turning vermin and pests into entertainers and celebrities to enhance chance of survival) by their very nature are also of benefit to humans therefore these could be confused with marketable products and as such are certainly are becoming less strange as time goes on. Concepts such as the Night Vision goggles for rodents remain to me, extremely odd. Although feasible hypothetically, who would pay for the development, manufacturing, distribution, fitting and maintenance?

The project exists on two levels, on the surface it’s a bit Chindogu, it can be read as a comic book with each of the concepts existing as a one-liner. On a deeper level it’s philosophical, exploring our developing relationship with animals and the role technology has to play in shaping both our live and theirs.

What I enjoy about the reception of the project is that it seems to be

accessible on both levels and its lack of contemporary strangeness doesn’t seem to be hindering its popularity.

Each year, a blogger discovers the Audio Tooth Implant, and then there’s a wave of posts on the blogosphere. Other bloggers write about it, re-discover it but very few question the fact that it might or might not be a real product they’ll be able to get their hands on soon. How do you explain that? Is the implant a body enhancement that many people would love to have? Are people still contacting you to know more about it?

As mentioned above the project created a mixed reaction, it was never meant to be taken seriously (although I have received a few complaints from nature lovers who thought I really was advocating the development of technology for animals). The Tooth Implant was different from inception. It was conceived as a project to explore the potential and ramifications of in-body technology (implants). Jimmy and myself were conscious that for the project to instigate a wide public discussion the concept had to exist on the borders of contemporary reality too extreme and it would be seen as science fiction, too conservative and it would just blend into the plethora of current technological gadgets available on the market. Initially we were honest about our motivations but it soon became clear that the press weren’t too interested in technological debate so we changed our methodology and went down the surreptitious route; by suggesting that it was a real product and would be available on the market at some point in the near future they took the bait. We learnt the correct technical jargon to explain how the chip would operate and built the model resin tooth as a representational graphic. Then after the project’s launch at the Science Museum in London the journalists took over and the myth was created. We perhaps spoke personally to around 20 individuals; the rest is copy, paste and exaggerate. New media such as the web have enabled news and stories to spread like viruses, mutating as they weave their way around the world. This has perhaps perpetuated the project beyond its normal lifespan, that together with bad journalism. In all the time the project has been public only one or two journalists have questioned its validity. A German reporter from Die Zeit called Harro Albrecht wrote a wonderful article in 2002 and last year we were contacted by Wired enquiring into the status of the project. We still get a lot of requests for the tooth image, it¹s still featured regularly in lad’s gadget magazines and people are still offering their teeth for experimentation.

As mentioned above the project created a mixed reaction, it was never meant to be taken seriously (although I have received a few complaints from nature lovers who thought I really was advocating the development of technology for animals). The Tooth Implant was different from inception. It was conceived as a project to explore the potential and ramifications of in-body technology (implants). Jimmy and myself were conscious that for the project to instigate a wide public discussion the concept had to exist on the borders of contemporary reality too extreme and it would be seen as science fiction, too conservative and it would just blend into the plethora of current technological gadgets available on the market. Initially we were honest about our motivations but it soon became clear that the press weren’t too interested in technological debate so we changed our methodology and went down the surreptitious route; by suggesting that it was a real product and would be available on the market at some point in the near future they took the bait. We learnt the correct technical jargon to explain how the chip would operate and built the model resin tooth as a representational graphic. Then after the project’s launch at the Science Museum in London the journalists took over and the myth was created. We perhaps spoke personally to around 20 individuals; the rest is copy, paste and exaggerate. New media such as the web have enabled news and stories to spread like viruses, mutating as they weave their way around the world. This has perhaps perpetuated the project beyond its normal lifespan, that together with bad journalism. In all the time the project has been public only one or two journalists have questioned its validity. A German reporter from Die Zeit called Harro Albrecht wrote a wonderful article in 2002 and last year we were contacted by Wired enquiring into the status of the project. We still get a lot of requests for the tooth image, it¹s still featured regularly in lad’s gadget magazines and people are still offering their teeth for experimentation.

What we¹re learned is that Brazilians love the idea of tooth implants, many people in the USA claim to already have them, planted by some secret government organisation and the Germans are very cynical about it (to their credit).

What did you try to achieve/investigate with The Interstitial Space Helmet? Don’t be offended but I tend to see that project more as an art project than as the work of an interaction designer. What’s your opinion on that?

This was a project that Jimmy and myself developed at Media Lab Europe, together with the Iso-phone. Both projects were an experiential comment on contemporary communication as mediated by technology. With The Interstitial Space Helmet (ISH) we were looking at the rise of digital mediation of human representation and how this challenges normative ideas of image, personality and communication.

This is one project that perhaps did start out with the complicated and strange user. Whilst placated in front of the screen, interacting with others via web cams and artificial personas they might run into problems dealing with real people in physical interactions. The concept blurs these two worlds, taking elements of the virtual into the physical. It is really a product for the Otaku generation, acknowledging the fact that the internet has created new forms of social interaction enabling new modes of behaviour and possibility. Online chat rooms, games and virtual worlds such as Second Life where we can be whoever we choose to be, exemplify this. Normative modes of behaviour and rules don’t exist and for some, these places are more comfortable than the physical world.

The Interstitial Space Helmet is strange today, but in 10 years time?

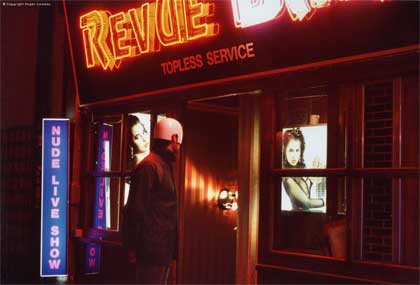

Social Tele-Presence looks like the perfect accessory for our Big Brother’d generation. What’s the idea behind the project? What does it comment on?

This is quite an old one. The original premise behind the early projects was that human evolution is not fast enough to keep up with technology; we are therefore in some cases the limiting factor, a hindrance to further development both physiologically and psychologically. An example of this is travel sickness a huge issue with the advent of space tourism. The concepts explored solutions to this situation, from post-human ideas such as implants or genetic modification to more simplistic methods such as tele-presence. (The experience of being fully present at a live (non-virtual) location remote from one’s own physical location).

Tele-presence is currently used for military and exploratory purposes, allowing the body to exist in dangerous or inhospitable physical environments. Taking this as a starting point it seemed that there was potential to shift from physically inhospitable situations to social. The camera and microphone that are part of the hardware were relatively easy to develop but the robotic element was extremely complex and problematic. To get around this I originally attached the camera/mic to a dog but later the rent-a-body service was conceived. This operated in two ways; a human body with all external senses removed is made available for use. Camera and mics are attached and the renter can use the body to explore and visit socially dangerous or inhospitable places. I imagined MPs and strip joints or blind dates for the chronically shy. The other service was parasitical tourism, achieved by attaching the camera to people in a different social circle to your own, a bit like Being John Malkovich.

I suppose the project does fit into the Big Brother theme but it’s really from a more personal perspective, a more active than passive relationship with the camera and screen.

You’ve spent some time in Japan to work for Issey Miyake. What were you doing exactly?

You’ve spent some time in Japan to work for Issey Miyake. What were you doing exactly?

Unfortunately and much to my chagrin I had to sign an NDA as thick as the yellow pages so am unable to talk about it at the moment. I can say that I worked with the A-POC team and Dai Fujiwara in particular who was and still is very inspirational. It was a great experience.

You’re now Tutor/Research Fellow at the department of Design Interactions, RCA, London. Could you give us more details about your role there? The kind of ideas or projects you’re developing with the students?

I spend 2 days a week on the research and one day teaching both 1st and 2nd year Design Interactions students. The course evolved firstly from CRD to Interaction Design and last year to Design Interactions. Basically it’s Interaction Design that incorporates emerging technologies such as nanotech, biotech, AI, pharmacology etc. It feels like home as these are the kind of areas I’ve been interested in since I graduated from the RCA, probably no coincidence as Tony Dunne (Head of Department) was my tutor in Design Products at the time.

It’s a very people centric approach with the students exploring how these new technologies may manifest themselves in mainstream reality. I’d say that my role is one of guidance, of helping to sift out the ideas with most potential and aid in the development of the project. We place a lot of emphasis on communication, presenting complex ideas about the future requires delicacy and imagination. Science fiction can offer some clues but tends to sensationalise technological possibility and therefore lessens the impact of the message. Design has the potential to operate much closer to the borders of reality, removing the fictional element and therefore begging the question of the audience: “is this real or not?” When projects reach this level, the viewers own imagination can take over; how would it be to live with such products? Would I like to exist in such a world? and the discussion is initiated.

Currently we have projects envisioning a future where the poorest utilise new possibilities of fusing nanotechnology and the body as real-estate; a series of proposals reinventing myth and legend in the 21st century; an exploration into the potential of virus as commodity and more traditionally a critique and series of proposals on the world of blogjects, to name but a few.

Any plans in the new future or new projects you’re working on?

We’ve (auger-loizeau) just finished a project for the Science Museum in London on the future of spying. The average audience there is 8-12 year olds so it was quite a challenge but we’re happy with the result. This opens on the 10th February.

The RCA research project, sponsored by Philips design is progressing well. I’m exploring the potential of smell and its role in human interaction and behaviour. Suddenly it seems like quite a fashionable area but hopefully I’ve a slightly different take on it, control being a major aspect of the concept: Smells reaching the nose and emissions coming from the body. I’ve found some fascinating research related to these issues and am currently building an operational prototype for experimentation and photographic scenarios. Basically the themes are dating, health, cooking and control of personal information.

Finally I’m working with Jimmy on an old project of his: Afterlife, an aid for the grieving process in a technologically mediated culture. It used to be featured on our website but after we came clean about the tooth implant we didn’t want people to think that this project was of the same nature. We’re collaborating with scientists and attempting to offer the service for real. Basically creating a microbial battery from the energy of a loved one that may then be used to power a range of electronic products. We’re at the early stages of development but keep an eye out for the new website, here we’re working with our usual graphic designer, Johnny Richards who¹s done some great work for us over the years.

Thanks James!