Firing a Kalashnikov assault rifle. Photo by Maja Dubowska

Dani Ploeger studied music in various conservatories across Europe, performed as a trombonist with symphony orchestras in Stuttgart and Berlin, taught music and performance in Ramallah, Palestine, completed a PhD on sound, performance and media theory at the University of Sussex, lectured in various universities in the UK and is currently a Research Fellow at The Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. But the reason why i’m interviewing Ploeger is that in his current life, he is a visual artist, a cultural theorist, and the leader of Bodies of Planned Obsolescence: Digital performance and the global politics of electronic waste, an art & science research project that explores the material aspects of electronic devices from their ecological, social, technological and ethical perspective.

I discovered his work last year at the Renewable Futures conference in Riga. He talked about his research on electronic waste, showed us a video of a performance for mobile phone that starred an erection and participated to the Transformative Ecologies exhibition with the video documentation of a performance that involved having electronic waste sewn onto his abdomen. Ploeger has since been learning how to use fire arms in order to be able to shoot at an iPad with an AK47, and travelled to dump sites in Nigeria to collect electronic waste originating from Europe.

At first sight, it might seem difficult to reconciliate topics as diverse as the ones enumerated above. But Ploeger is an artist who looks at the broad picture, who realizes that e-waste, sexuality, ecology or violence are all valid points of entries into the study of the many paradoxes, complexities and entanglements of our consumer culture and its impacts on the planet.

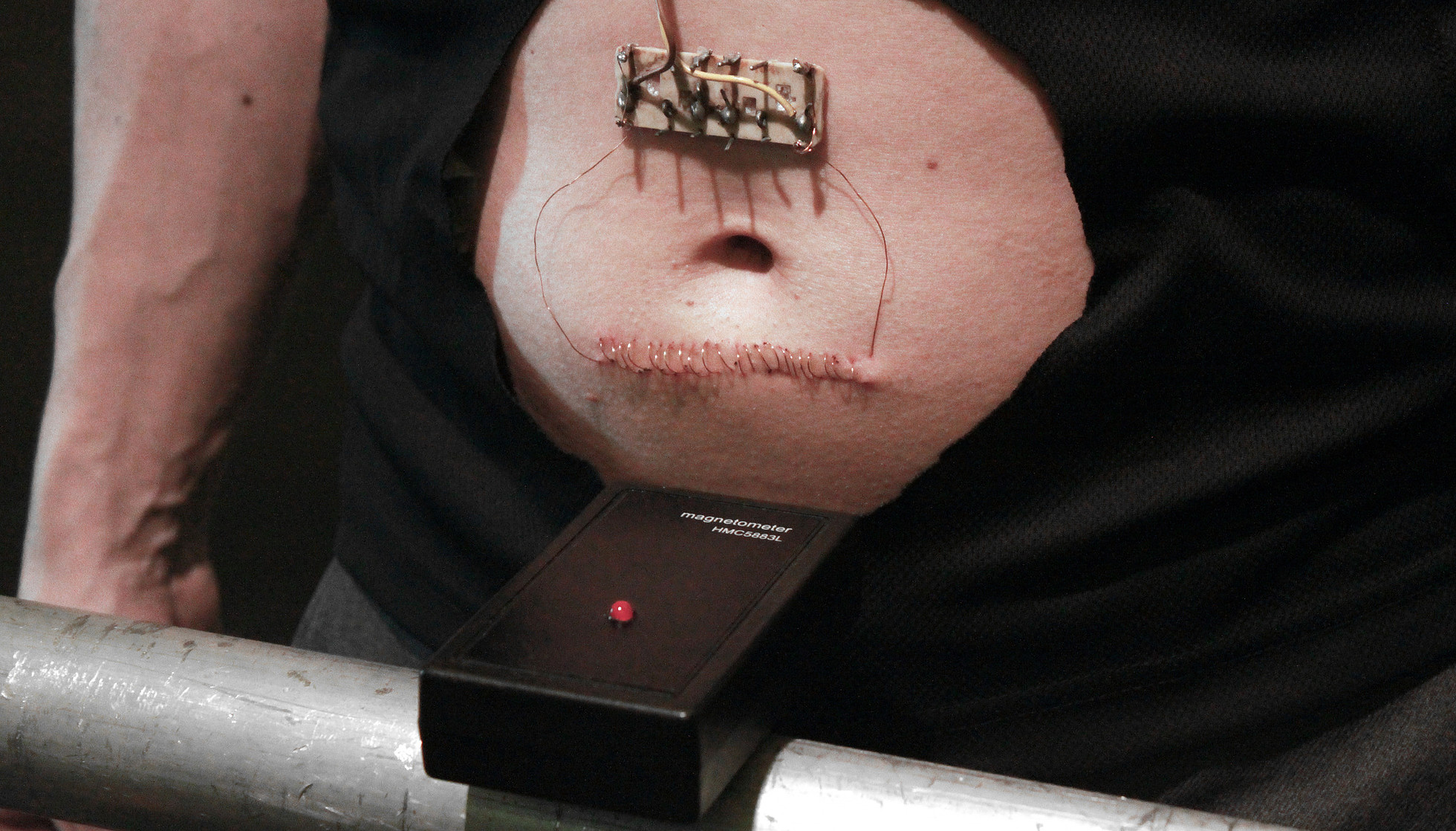

Dani Ploeger, Recycled Coil, 2014

Hi Dani! I found the video of your work Recycled Coil really difficult to watch. For the performances, you asked a body piercer to sew an old cathode ray television coil into your abdomen. I thought it was a violent way to treat your body, especially because you were not doing it for aesthetic purposes and also because you used something we regard as trash.

Did you want to get a visceral reaction from people? And what were you trying to achieve with the performance?

With Recycled Coil I wanted to create a counterpoint to the commonplace image of the hi-tech, powerful cyborg, which still dominates popular culture (think of Robocop, the Terminator, and – more recently – Ava in Ex Machina). Instead of extending my body with state-of-the-art new technologies in order to make it more durable or enhance its functionality, I implanted old, discarded parts to perform one of the most simple things one can do with electricity: generate a magnetic field by sending a current through a coil. The magnetic field was so weak that whilst it could be detected with a sensitive magnetometer it was not suitable for any ‘useful’ purpose.

I see the cultural hegemony of the hi-tech cyborg, with its slick and clean surfaces, as part of what I call the ‘symbolic order of technological progress’. Through advertising, news media and popular culture, everyday digital technologies are propagated in relation to ideas of progress, and immaterial forms of communication. The materiality and eventual becoming-waste of the devices, as well as the fleshiness of the bodies it interacts with, tends to be backgrounded in these visions.

I like to see Recycled Coil as a technological extension of my body that draws attention to its vulnerability, and to the materiality of technological devices as objects that remain in the world long after they have lost their aura of newness. In this context, evoking a sense of the abject and focusing on the bloodiness of the operation was deliberate.

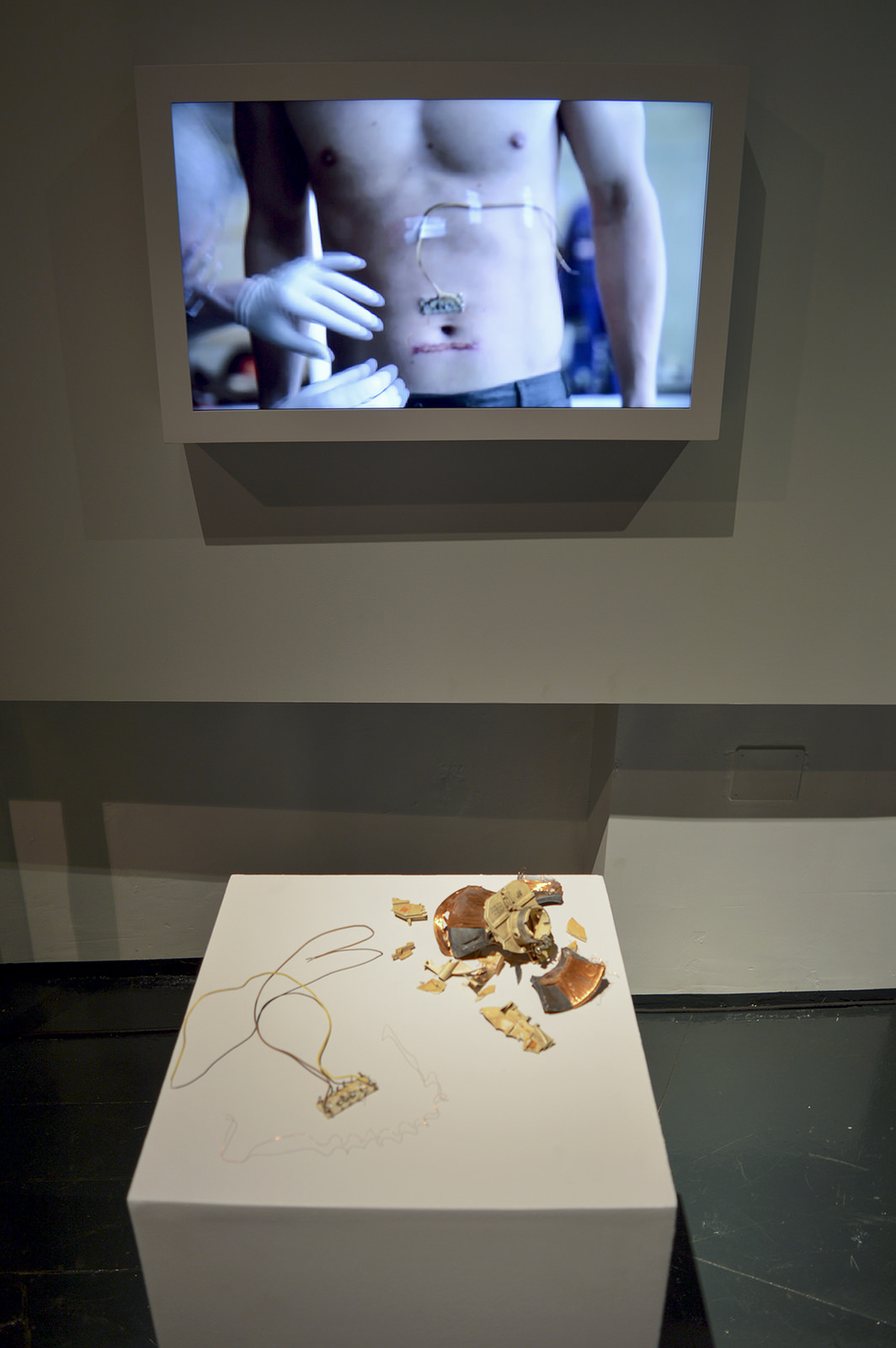

Dani Ploeger, Recycled Coil, 2014

Dani Ploeger, Recycled Coil. Installation view at the Transformative Ecologies exhibition in Riga. Image courtesy of RIXC

I’ve also been wondering about the place that porn takes in your work. Some of your works, such as Ascending Performance, can be enjoyed both as artworks in their own rights and as sex entertainment. Is this a strategy to engage with non-traditional art audiences? Maybe i’m a bit naive but don’t you think it’s a bit risky? Because art audiences might take you less seriously?

I’m not very worried about being taken serious by ‘art audiences’, but if I was, I think my worries would be focused elsewhere. Andy Warhol, Jeff Koons and many others have also made work that can be enjoyed as sex entertainment (e.g. Warhol’s Blow Job and Koons’ Made in Heaven) and I don’t think they have been taken less seriously as artists for that reason. However, I have never seen smartphone apps, body piercing, and electronic waste featured in Artforum International or other ‘serious’ art magazines…

Recycled Coil was conceived as a response to popular ideas about technologized bodies. Similarly, ASCENDING PERFORMANCE tries to uproot some widespread attitudes to bodies and nakedness in digital culture. Whatever the intentions and original representational framework of bodies you put online, you can be sure that they will be sexualised. This becomes clear when you read the comment feeds of Youtube clips, or look at the profiles and interests of people who ‘like’ art videos featuring naked bodies on Vimeo. With ASCENDING PERFORMANCE I wanted to make an artwork that acknowledges this by deliberately sexualizing the representation of my body, and distributing it through a porn platform, whilst at the same time complicating its straightforward appropriation as sexual entertainment.

Dani Ploeger, Ascending Performance (Trailer)

I simultaneously advertised the work in Artforum International (in November 2013) and on pornhub.com to promote it as both art and porn (the decision to advertise in Artforum rather than another art magazine was conceived as an homage to Lynda Benglis’ famous 1974 advertisement with double-sided dildo in the same publication). The app itself also refers to both artistic and pornographic frameworks: Just like in ‘porn-proper’ you get to see a hard dick. However, in contrast to the HD and POV (point-of-view) immediacy of most mainstream porn, the mediation of my body is emphasized in this app; the video is a grainy, digitized Super 8 film. Similarly, the toned texture of my body is heightened with bodybuilder tan and glaze to suggest a typical porn star body, but this is then ‘artified’ through the film’s rather distantiated perspective, the sepia-like colours, and the absence of a money shot (i.e. there is process but no conclusion).

Advertisement for ASCENDING PERFORMANCE in Artforum International. Photo: Courtesy of DEFIBRILLATOR GALLERY, Chicago, IL

Advertisement for ASCENDING PERFORMANCE on pornhub.com. Photo: Courtesy of DEFIBRILLATOR GALLERY, Chicago, IL

Bodies of Planned Obsolescence: Digital performance and the global politics of electronic waste is a network of artists, scientists and theorists looking for ways to engage with the material aspects of electronic devices. And how did the work of artists support the one of scientists? And vice-versa?

The central idea of Bodies of Planned Obsolescence was to re-materialize the participants’ experience of electronic devices, which tend to be promoted in relation to notions of immateriality (e.g. ‘the cloud’) and everlasting newness in Western consumer society. We tried to achieve this by means of hands-on workshops where the participants actively took part in electronic waste recycling work in countries that import substantial amounts of used technology from Europe (Nigeria) and North-America (China via Hong Kong). After these workshops we exchanged experiences and ideas and took this as a starting point for new work in our respective disciplines (digital art, cultural studies, science).

The collaboration with experts on the subject matter from the realm of science and cultural studies enabled the artists participating in the project to develop their work in an environment with a diverse range of in-depth, detailed knowledge.

On the other hand, the artistic perspective of the projects’ methodology meant that we could conduct the workshops with a blue-sky approach, without clearly defining hypotheses prior to the activities. Also, we could engage in activities that involved the deliberate exposure of the participants’ bodies to a certain degree of risk (especially the informal recycling methods practiced in Lagos involved some health hazards). For the scientists in the group, but also for some of the cultural theorists, this would have been a highly unlikely approach if they had worked within their own disciplines. Whereas blue-sky experimentation and negotiating exposure to physical risk is a common aspect in many performance art practices (an extreme example is Chris Burden’s Shoot (1971) where he asked a friend to shoot him in the arm), the avoidance of any risk is a priority in most institutional science research.

Could you tell us about the workshops in Lagos and China? What have you and the other participants discovered there? What can points of views and approaches in these countries teach Europeans?

In Lagos, we visited a dump-site connected to Alaba Market in the western outskirts of the city. We asked a group of workers if they would give us an induction into the work they do. Subsequently, we worked alongside them in the dismantling of computers and other electronic devices for two days. We extracted copper and aluminium from motherboards and adapters, removed scrap iron from televisions and I tried to take apart refrigerator pumps (which turned out to be much harder than it looked).

Project participants Jelili Atiku and Dani Ploeger at a dump at Alaba Market in Lagos, Nigeria. Photo by Peter Dammann / Agentur Focus

In Hong Kong, we worked at one of the main e-waste recycling factories in the outskirts of the new territories, close to the Chinese mainland border. In this formalized industrial environment we attended an induction in health and safety protocols and subsequently worked in the factory where we used pneumatic tools to dismantle laptops, monitors and desktop computers, and sorted all parts to prepare them for dispatch to mainland China for further processing. There are more detailed accounts of the workshops in Lagos and Hong Hong on the project blog.

Project participant Shu Lea Cheang at Vannex International Ltd. recycling plant, Hong Kong. Photo by Peter Dammann / Agentur Focus

During the workshops I became interested in the ways in which ‘dead’ electronics act on the body. Rather than the common perception of waste as passive matter that is moved and manipulated by human actions, the waste environment itself also acts on the bodies that navigate it. In contrast to some of the work I had made before this project, which had focused on identifying, collecting and assembling various kinds of e-waste (e.g. the installation Back to Sender (2013-14) in collaboration with Jelili Atiku), in the aftermath of the Lagos visit I made a piece that documents a wound that started to occur on my arm after working on the dump-site for two days (Hi-Tech Wound (2015)).

Hi-Tech Wound, 2015, duratrans print

One of the participating scientists, Kehinde Olubanjo, experienced the omnipresence of dust at the recycling sites and considered its apparent contents of waste particles. He is now planning a research project where samples of dust, rather than the e-waste artefacts themselves, are analysed to assess environmental hazards.

A more general dimension that we became aware of were the thriving electronics repair activities that surrounded the recycling work in Lagos. Repair workers from the adjacent market areas would frequently visit the dump to buy parts harvested from the e-waste. This active repair culture, which is generally characterized by a high degree of inventiveness and improvisation, is found in various African countries and could be a positive example for the technology-throw-away attitude that is prevalent in the West.

This thought formed the starting point for an event I am organizing at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London on 15 April. The event will include a presentation of digital artwork that deals with electronics, waste and longevity, and I will travel to Nairobi, Kenya, where I will set up a live video connection with the museum to interact with a repair community there. This will be the setting for a repair workshop where visitors are invited to bring their own broken devices and receive guidance in basic repair skills.

Do you think that the planned obsolescence issues is entirely in the hands of the manufacturers? Or can citizens and cultural institutions engage effectively with the issue?

I consider rapid product obsolescence inherent in the logic of capitalist consumer culture. Consequently, an effective solution to the issue would involve change on a much bigger scale. Initiatives that engage directly with waste prevention and recycling are useful to temper short-term effects, but as long as we maintain a culture based on economic growth through ever increasing consumption rates, initiatives to increase recycling and extend product lifetime cannot be considered more than a patching strategy. The V&A event I just told you about is based on a direct engagement approach, but through the artistic element, as well as the choice of topics that will be discussed via the video-stream, it will also take this as an opportunity to tease out broader, meta-perspectives on the issue.

I believe that what we should engage with – regardless of whether we’re artists or not – is exposing the contradictions of the ideology of consumer capitalism, and facilitate its collapse once the time is right. I am aware that in these days of ideological fatalism, this may sound like a fantasy project. And admittedly, I enjoy consumer culture too much myself to live up to such revolutionary zeal. However, I think that this is why my work always has a somewhat silly dimension as well.

While ambiguously indulging in consumerist practices and simultaneously undermining its glamorous promises, I hope it shows that consumer culture is in the end just a stupid circus event that destroys people and the world. Hopefully a future generation will have the strength and decisiveness to do away with it. And with me.

Do you find signs that consumers, manufacturers and governments in Europe (or the US, Australia, etc.) are taking steps into engaging more responsibly with planned obsolescence and with e-waste in general? Or is it still an issue that is swiftly swept under the carpet?

There seems to be a somewhat increased awareness due to the media coverage around the subject in the past couple of years, and there are some really good initiatives to encourage people to repair their broken devices. The Restart Project in London, who participate in the V&A event mentioned earlier, are a great example of this. Likewise, there are some positive manufacturing developments in terms of modular devices, such as the Fairphone, which are easier to repair and allow for specific parts to be exchanged.

However positive, these are relatively small scale initiatives though, which I think are unlikely to challenge the prevalence in mass culture of fast obsoleting disposable technologies. Again, in my opinion a solution to the electronic (and other) waste issue is unlikely to be achieved in isolation from a much more fundamental change in the organization of society.

Dani Ploeger, ASSAULT (iPad/AK47) official trailer, 2016

Any upcoming work, event, field of research you’d like to share with us?

The work we just talked about deals with techno-consumerism in relation to waste and sex. At the moment I am also looking at experiences of violent conflict in media culture, which I see in connection to these other two dimensions. Over the past two months I have been working on a new work with iPads. I fired a Kalashnikov at a functioning iPad somewhere in Poland and made a high frame-rate video recording of the bullet hitting the screen. This video material will form the basis for a new app, which will be released in May. The app will repeatedly play the video and sound recording of the destruction of the screen, after which the recording is played backwards in slow-motion. Thus, the iPad will show an endless process of its own destruction and apparent regeneration. Ironically, I am now generating e-waste, the process and artefacts of which are subsequently rehabilitated as an artwork…

Shot iPad. Photo by Maja Dubowska

Over the past decades, warfare in Western nations has increasingly become understood as a clean and hidden affair. On one hand, Western ‘Shock and Awe‘ operations appear to be precisely controlled by computer game-like technologies, such as drones and guided precision missiles. On the other, terrorist attacks on Western societies have mainly evolved around hiding Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs) in inconspicuous places and are thus hardly considered as proper warfare strategies. As a result, in the West, an apparent division has been established between ‘our’ world of organized consumer space – albeit under threat of occasional improvised violent disturbance – and ‘their’ world of persistent ‘dirty’ ground warfare, which takes place in underdeveloped territories far away from Europe and North-America.

In recent terror attacks in Belgium and France, a shift has taken place though. The iconic image of the battlefield soldier has re-emerged in perceptions of the everyday in Europe: terrorists and security forces in military attire and armed with automatic weapons appear to increasingly populate experiences and imaginations of public space. Instead of improvised bombs, the Kalashnikov rifle is now becoming the iconic weapon of terrorism. In Assault, I’m trying to bring these conflicting ideas of ‘clean’ consumerism and ‘dirty’ battlefield warfare to a material collision.

Thanks Dani!

The public workshop Digital Futures: Dreaming Zero-Waste: The art of fixing electronics in Europe and Africa will take place at the Learning Centre Seminar Room 3, Victoria and Albert Museum in London this Friday 15 April 2015.