War and Medicine Credit: Wellcome Library, London

War and Medicine Credit: Wellcome Library, London

As i mentioned earlier, finally got to visit The Wellcome Collection, a museum in London dedicated to health and medicine. The Collection is based on the artefacts amassed through the years by Sir Henry Wellcome. This turn-of-the century pharmaceutical entrepreneur and collector was hoping to create a Museum of Man one day. The Wellcome Collection features a permanent exhibition of his artifacts as well as temporary exhibitions. They are spectacularly fascinating and have the good taste of mixing scientific and artistic displays.

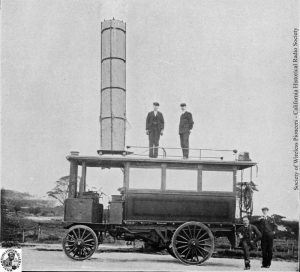

War and Medicine, Wellcome Collection Credit: Wellcome Library, London

War and Medicine, Wellcome Collection Credit: Wellcome Library, London

War and Medicine, Wellcome Collection Credit: Wellcome Library, London

War and Medicine, Wellcome Collection Credit: Wellcome Library, London

When i checked the place out, War and Medicine was on the programme. It was, to say the least, quite graphic. Not grossly graphic but elegantly upsetting. As James Peto, the curator of the show, explained, the necessity to repair and heal has to adjust constantly to advancements in the art of hurting and killing:

“I suppose what the exhibition is really about is the struggle of doctors, nurses, surgeons and research scientists to keep up with the pace of development of weapons and armaments,” Peto says. However, progresses do not prevent the existence of disheartening paradoxes: “Survival statistics among soldiers are hugely improved, but civilian casualties of terrorist attacks and bombs apparently intended for soldiers seem to be growing.”

Concentrating on the modern era, the exhibition explores the intimate relationship between warfare and medicine, beginning with Florence Nightingale in the Crimean War in the 1850s, and continuing through to today’s conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The prologue of the show is a video installation by David Cotterrell who spent a month in Afghanistan gaining first-hand experience of life beyond the front line, after he realized that he is part of a generation that not only was not required to join the military but that is also the last one to have living relatives who experienced the Second World War.

Patient in plane. Credit: David Cotterrell, 2008

Patient in plane. Credit: David Cotterrell, 2008

Ambulance. Credit: David Cotterrell, 2008

Ambulance. Credit: David Cotterrell, 2008

He observed and captured the daily life of soldiers through film and photography that immerse viewers in the realities of contemporary battlefield medicine.

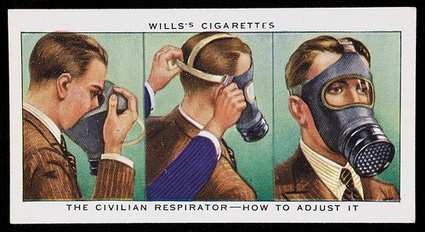

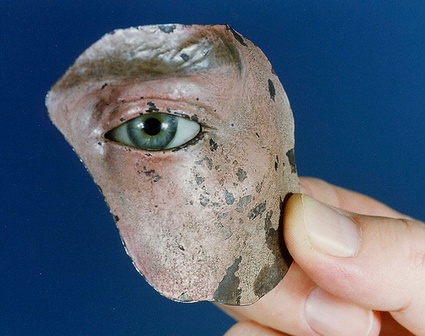

War and Medicine displays all sorts of memorabilia: old posters warning soldiers against STD, gas masks, bandage with instructions printed on it, old surgical instruments, tin facial prostheses, a brain specimen damaged by a shell splinter and kept in formol, photographs, a portable liturgical kit to enable military chaplain to deliver the last rites, etc.

Liturgical kit

Liturgical kit

One of the core discoveries of the show for me was that each major conflict has stimulated great advances in a particular branch of medicine. For example, a series of photos showing the result of pioneering skin grafts on a soldier with a missing nose attests that a priority of WWI was facial reconstruction.

Tin face, 1918. Credit: Gillies Archives, Queen Marys Hospital, Sidcup UK

Tin face, 1918. Credit: Gillies Archives, Queen Marys Hospital, Sidcup UK

WWI brought soldiers disfigured by shrapnel from exploding shells and gunshot wounds. Facial reconstruction would start in a rudimentary fashion with tin face masks. Made of thin copper, the mask were sculpted to match the portraits of the men in their pre-war normality. They were then painted and finished while the patient wore it, in order to most accurately match the tone of the flesh with the enamels (via.)

On Project Facade is a stunning silent film clip that shows Anna Coleman Ladd and Francis Derwent Wood crafting and fitting tin facial prosthetics to injured servicemen circa 1916.

Surgeon Harold Gillies, considered to be the father of plastic surgery, persuaded the army to establish a purpose-built site that would treat facial injury in a more sophisticated way. The Queen’s Hospital, Sidcup opened in 1917. Gillies and his colleagues developed many techniques of plastic surgery; more than 11,000 operations were performed on over 5,000 men (mostly soldiers with facial injuries).

Percy Hennell portrait. Credit: Courtesy of the Anthony Wallace Archive of the British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery (BAPRAS)

Percy Hennell portrait. Credit: Courtesy of the Anthony Wallace Archive of the British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgery (BAPRAS)

The most fascinating story is the one of Harold Gillies’ German counterpart, Jacques Joseph who treated many soldiers who had received facial wounds during World War I. In the 1920s, he set up a private practice where he developed and performed rhinoplasty on many of Berlin’s Jewish community (to which he also belonged). He would sometimes even ‘fix’ the noses of poor Jews for free helping them to “vanish” into German society.

Joseph died in 1934 but his reputation survived World War II, partly due to the many rhinoplasty instruments he designed, which still bear his name today.

Nasal reconstruction instrument belonging to Jacques Joseph, c.1930. Image credit: Antony Wallace Archive, British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons at the Royal College of Surgeons, London

Nasal reconstruction instrument belonging to Jacques Joseph, c.1930. Image credit: Antony Wallace Archive, British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons at the Royal College of Surgeons, London

At the time, plastic surgery was much less a matter of vanity than an attempt to cure the psychological depression that arose with a loss of the appearance of a bomb-damaged soldier. The section of the exhibition dedicated to psychological trauma was actually where one could see the most unsettling material.

Extracts of a film shot right after WW2 show soldiers who were released from the army because of emotional difficulties. Titled Let There Be Light and directed by John Huston follows U.S. soldiers from World War II as they are treated in a clinic for a condition then described as “psychoneurotic” illness, (commonly known today as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder PTSD).

You can find extracts of the movie on youtube.

The film was commissioned by the US but the way it portrayed the suffering of shell-shocked soldiers was so uncompromising that the movie remained banned until 1981. “What this also highlights is how far we’ve come in terms of taking psychological issues seriously – at the time, these men were referred to as ‘psycho neurotics’. It’s the same condition that led to men being executed for deserting their posts in the First World War,” says Peto.

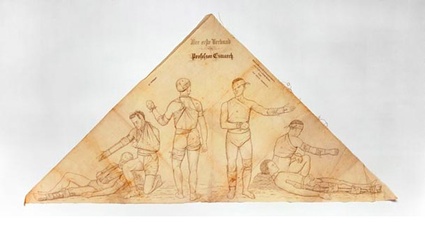

And now ladies and gentlemen, a mix-match of images from the image gallery of the show:

Image: Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, Dresden

Image: Deutsches Hygiene-Museum, Dresden

The original version of this cotton bandage was designed by Professor Friedrich von Esmarch, who had been Surgeon General to the German army during the Franco-German War (1870-1871). This later example, designed for use on the battlefield, could be used open or folded and applied in 32 different ways as per the printed instructions on its surface.

The Royal Pavilion, 1914-15. Image: The Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton and Hove

The Royal Pavilion, 1914-15. Image: The Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton and Hove

In order to accommodate the massive numbers of casualties in World War I, numerous buildings were requisitioned as military hospitals, including mansion houses and casinos.

One of the most elaborate hospitals was the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, which opened its doors to hundreds of wounded Indian troops returning from the battlefields in France.

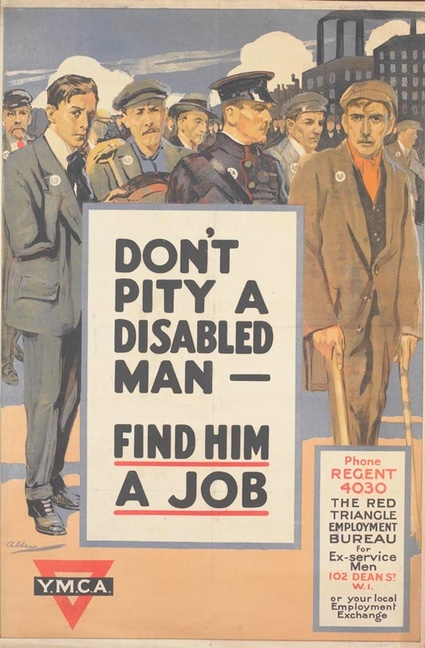

Don’t pity a disabled man – find him a job, WWI. Lithograph on paper by Abben. Image: Imperial War Museum

Don’t pity a disabled man – find him a job, WWI. Lithograph on paper by Abben. Image: Imperial War Museum

In the aftermath of World War I, eight million veterans returned home permanently disabled. Social reintegration presented a range of issues from employment to disability rights and war pensions. Like many charities extending their remit in the wake of the war, the YMCA set up an Employment Department that found jobs for 38 000 ex-servicemen.

Image galleries. On the homepage: Chinook helicopter, 2007. Credit:David Cotterrell, 2008.

Related story: Interview with Paddy Hartley.