This year, Alyaksandr Lukashenka will be celebrating 30 years of ruling Belarus with an iron fist. The last presidential election, which took place in August 2020, was heavily contested. There were massive protests and ruthless repression of dissent. Today, Belarusian authorities continue to curb the rights to freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly. Torture, suspicious deaths in custody and other ill-treatment remain endemic. The justice system is systematically abused to eradicate dissent. Freedom of expression remains severely restricted. Dozens of independent journalists, intellectuals and bloggers have been arrested. Musicians and other artists have fallen victim to the crackdown on criticism. Belarus might look like a bleak place for human rights at this moment, but it is also a country where citizens have demonstrated, time and time again, that they have ingenuity, determination and a desire for change. And, as the work of artists like Ivan Burakin demonstrates, Belarusians also have courage and a sense of humour.

Ivan Burakin, ROYGBIV

Ivan Burakin, Workers, 2022

Burakin is a post-documentary photographer and visual artist who works mostly with digital archives and sometimes with video. His projects focus on national and personal identity, collective memory, propaganda, as well as the influence of mass media on the world.

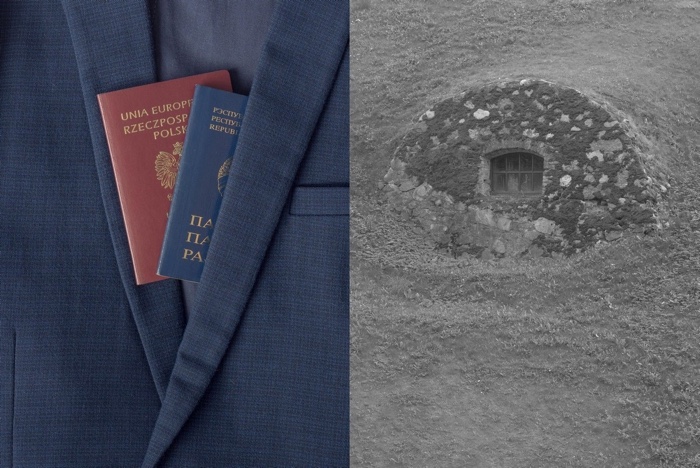

With his background in foreign languages, two citizenships and a few years living abroad, Burakin has both an external and an insider view of Belarus. He has an intimate understanding of its society but he has also developed the perspective of someone who can look at it from the outside.

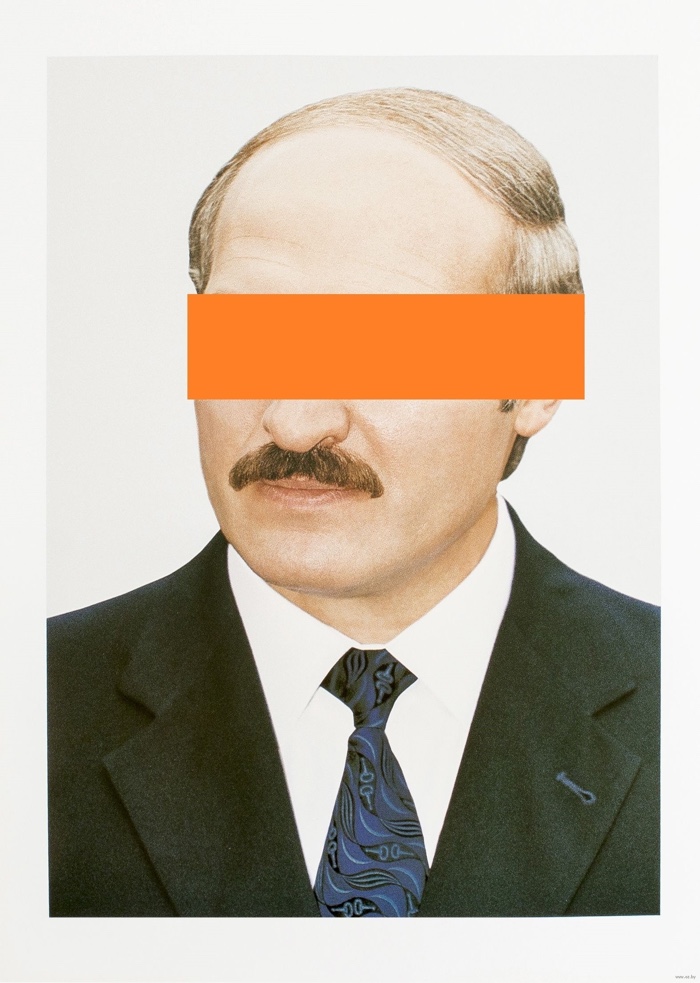

His ambiguous position is articulated in What if I Am a Spy?, a series he made in 2018. Upon returning to Belarus after long sojourns abroad, the artist embarked on a project that looked at the national identity of Belarusians. He quickly realised that people reacted to his shooting in the street with distrust. Even though he was photography openly and in non restricted areas. Someone even asked “Are you a spy?” Since wariness had become part of the national identity of his fellow citizens, Burakin focused his pictures of the most mundane elements of the urban environment, wondering what was suspicious there and whether he himself had become some kind of spy.

Since then, the artist has been documenting Belarusian society using material that is already there, archival images that fit the Lukashenka narrative. Ironically, this existing, approved material makes the viewer perceive with acuity the soul-crushing, authoritative nature of the government better than any image of brutality could do.

Ivan Burakin, #будущийзащитник (youngsoldier), 2019-

Hi Ivan! Your bio says that you identify yourself as a post-documentary photographer and visual artist. Could you explain to us what you mean by post-documentary?

To me, post-documentary means dealing with the topics documentary photographers or photojournalists usually deal with, but in an indirect way. For example, using screenshots, which I do a lot, or working with archives. It’s when the message is primary and the image is rather secondary.

Ivan Burakin, Watchers, 2022

Ivan Burakin, Watchers, 2022

Ivan Burakin, Readers, 2022

Ivan Burakin, Readers, 2022

Ivan Burakin, Readers, 2022

The “… Volution” body of works seems to be the most politically-minded. Apart from the video Committing Thoughtcrime, each series seems to remain on the threshold of what is barely acceptable for the government. The various series show workers operating machines or standing in line during a visit by Lukashenka, people watching the president’s speech live at their workplaces, people reading “Honest Newspaper” — a newspaper distributed by propagandist Telegram channels… You didn’t make any of these images directly. Instead, you either selected material found online or took screenshots from official video reports. Still, the accumulation of the images and the fact that you are an artist who has widely travelled is already suspicious. So i was wondering how you know whether or not your photo series will be regarded as non-threatening, not sarcastic and non-critical by the government. Because it does look like a perilous exercise to me. Or maybe I am naive? How do you know how far you can go?

Well, I don’t know, actually, and that’s one huge problem. I mean, I literally don’t know. And it’s a very distinctive feature and deliberate policy of the regime – they want people to feel uncertainty. The less certain you are (of anything), the fewer moves you make, because you believe that any of your moves can be illegal and therefore punishable. I mean, I have no idea whether they know about me at all. I hope they don’t. And I have no idea how far I can go. I’m pretty sure that they don’t know it themselves, since now there are no rules any more, literally.

Did I go too far with my projects? I might have, but I don’t know for sure. That’s why we have to take a tonne of precautions here. For example, cleaning browsing and search history all the time, unsubscribing from anything political, deleting all your potentially unsafe activity online (comments, likes, shares, mentions), unfriend those who have “political” profiles or just “political” profile pictures. By “political profile” I mean someone on Facebook, for example, who left Belarus and keeps posting news about the regime or openly supports political prisoners. Because yes, if you get detained and among your friends there is someone “political” you get arrested or fined a huge sum of money. Although it’s also true that if you get detained and you are crystal clean, they may take your phone, subscribe you to an extremist YouTube channel and charge you for this very subscription. And you can be sure that there will be about 10 witnesses who saw you watching that channel in a public place and commenting on it loudly. All of those 10 witnesses will happen to be from the police, by the way.

And I don’t mention deleting all the politically unsafe files (images, videos, documents) and emails from your computer, along with any printed materials (books, newspapers, leaflets), T-shirts, stickers, keychains, etc.

And the worst part is that you just don’t know what became illegal today, since the list of extremist materials and forbidden things is growing all the time.

In the video Committing Thoughtcrime, you are filmed thinking about the destruction of the independent press in Belarus, about riot police killing people in Belarus, about imprisoned opposition leaders, about people dying under very suspicious circumstances, about police torturing political opponents in a detention centre, etc. You go into details by giving the names of political opponents, independent journalists or protesters who have been victims of state brutality. I personally found the video very moving (especially after I had read the stories of Raman Bandarenka, Siarhej Tsikhanouski, Vitold Ashurak, etc.), so I can only imagine how hard-hitting the video must be for many Belarusians. Has there been any official reaction to the series? Any warning or reason to worry about your own safety?

No warning or official reaction so far. Do I have reasons to worry about? Well, a lot of. For example, I speak foreign languages, that’s enough to make me look suspicious here. Among them there is Polish, the language of the country which, according to our officials, is constantly training terrorists, assassins and spies to attack Belarus. Moreover, I give private lessons of Polish. (My students are Belarusians who had to leave the country after 2020. I won’t be surprised if the regime interprets my teaching either as some kind of training of future spies/assassins/terrorists or that I am being paid (sponsored, as they call it) by some “terrorist/extremist organization” from the abroad in order to harm Belarus in any way possible.) Then, I have two citizenships – Belarusian and Polish. Again, a perfect spy story. And finally, I speak Belarusian (not Russian) in daily life. Yes, speaking Belarusian, a national and one of the two official state languages, in Belarus is a very clear sign of someone who is not a fan of the regime. No one ever saw a single pro-government Belarusian-speaking person.

I understand that it may sound odd: why would someone stay in a country in such dangerous circumstances? Well, it’s a bit more complicated than it sounds. The thing is that they don’t hunt (yet) those who speak Belarusian, who teach Polish, or who have two citizenships. It’s rather that you try not to get detained for anything so that they don’t have a closer look at you. Of course, it concerns only those who didn’t take part in the protests in 2020 or later. Because if you did, they’d come for you as they keep coming for people, four years after the protests. They use surveillance systems, and they filmed as many people during the protests as they could, so now they just have to watch thousands of hours of those videos and identify those they can. And they do, unfortunately.

And yes, I can leave Belarus at any moment, just buy a ticket and be gone the next day. But since so many people have already left and not so many photographers or artists have stayed, I’ll try to stay here as long as possible in order to witness for myself what’s happening to my country, because understanding of the real situation from the outside gets very distorted, as I can see from those who had to leave the country. Besides, I also try not to fall into this omnipresent paranoia.

And I don’t live in Minsk, which makes quite a difference. Minsk is the regime’s target number one. The biggest protests took place in Minsk; that’s why the police focus on Minsk in the first place.

Ivan Burakin, Listeners, 2022

Ivan Burakin, Listeners, 2022

What does the title “…Volution” mean? Is it a safer way to evoke revolution?

No, it means that I’m not sure what it was, what happened to us. Was it a revolution as it’s often mentioned in media? But then it failed, since the people didn’t change the government. Or maybe what happened is evolution, a natural way things have to evolve in societies like the Belarusian one? Or perhaps there was a revolution in the minds of the people, and they finally decided to act and try to change something in their country? So, it’s “…volution” with some missing parts, but what exactly is missing I’m not sure myself.

Ivan Burakin, What if I Am a Spy?, 2018

Ivan Burakin, What if I Am a Spy?, 2018

Ivan Burakin, What if I Am a Spy?, 2018

Ivan Burakin, What if I Am a Spy?, 2018

In the description of What if I Am a Spy?, you explain that when you returned to Belarus after several years abroad, you wanted to make a photography project on the national identity of Belarusians. Six years later, do you think that you are closer to being able to portray the identity of Belarusians? How easy is it? Your work suggests that there is a lot of silence, caution and self-censorship in the country.

OK, I have to start with why I wanted to make a project on our national identity in the first place. After I spent a couple of years in Europe, I realised that people there knew almost nothing about us. And when they do, it’s mostly stereotypes or the belief that “Belarus is somewhere in Russia, isn’t it?”. Or, which triggers me not less than the above-mentioned, that Minsk represents the whole of Belarus.

Eventually, I understood that it’s quite logic, since mostly Minskers travel abroad and so spread a word about Belarus from a Minsk perspective. And also the fact that Belarusians don’t speak foreign languages (even English) en masse, so we kind of don’t talk about ourselves; it’s rather foreign journalists/authors/photographs coming here and gathering information in the country that they don’t understand. And they also mostly come to Minsk, which again doesn’t represent the rest of the country at all.

Being a multilingual person, I felt that I wanted to be that bridge between Belarus and the world, I wanted to show that we are not Russia, and I wanted to show that Minsk is very different from the rest of the country. That’s why I decided to make a project about Belarusian national identity first. But in the process, I understood that I had no idea what that identity was. So I just went hiking all over the country and took pictures. And then the spy story started to emerge.

Coming back to your question, I’d add that, as of 2024, there is not only a lot of silence, caution and censorship in the country, but also absurdity, oppression, fear, hopelessness, despair, hate, injustice and so on.

I love how you played with the ambiguity of the images in “What if I am a spy?” Do you feel that after spending several years looking at fellow Belarusians, you have eventually turned into some kind of spy?

I think it’s rather that reality turned into an even worse version of itself than it was in 2018. Back then, it was absurdly fun; today it’s extremely absurd, but it’s not fun any more. Frankly speaking, I can’t say that I’ve been looking at people, at Belarusians. As you can see from my images, I’m trying to avoid people in my photos when it’s possible. The What if I am a spy? project was born out of irritation by people. By the way, the most correct way to pronounce the title is with the “am” stressed: “what if I AM a spy?”.

One day, after another encounter with somebody who said I was “a spy or something” I was walking back home and talking to myself and that monologue was something like that: “Damn, what’s wrong with these people? I was taking a picture of a wall in broad daylight. That wall was of no interest to any spy in the world. And how stupid a spy should I be, doing the job like that, with no disguise and stuff? How am I supposed to make a project about our national identity if I just don’t get these people and they don’t get me? How come I’m being taken for a spy? Wait… but what if I AM a spy? What if I make a project about this paranoia, which seems to be part of our today’s national identity?”. And that’s how the project was born. So, referring to the part of your question about fellow Belarusians, I’ll add, that I’m looking rather at the totalitarian machine than at people.

Ivan Burakin, Workers, 2022

Ivan Burakin, Workers, 2022

Ivan Burakin, Workers, 2022

On your website, there is a list of exhibitions you participated in. I noticed that your work is exhibited all over Europe, but it is seldom shown in Belarus. How much of a career can you develop in your own country? Especially when your work focuses on the propaganda and violence taking place in your own country?

Well, it’s hardly possible to develop an independent artistic career in Belarus today. Although before 2020, it wasn’t much better either. Not just because it can be dangerous. Even if you stick to totally non-political stuff, there are no places you’ll be able to show your works at: no festivals, no galleries, no curators, no market, no press. And if there are any, there is still censorship. That’s why those artists who decide to collaborate with a gallery or a festival may be asked to express some loyalty to the state. So it’s not enough not to support the protesters, today you have to show open support for the government and its policy. Independent culture is literally dead.

What substitutes the culture is interesting only from the anthropological point of view, since it’s a culture serving the regime, nothing more. There is no freedom of artistic expression, no challenging, no questioning, nothing.

That’s why I’d rather try not to be seen here in Belarus; it’s just safer at the moment. But of course I long for communication with other artists, for exhibitions and workshops, for active artistic work, which is possible only outside of Belarus and rarely happens in my case.

What’s next for you? Any upcoming events, projects or research you’d like to share with us?

Yes, both events and projects. I’ve been chosen for a two-month residency in Germany in 2024. There, I’ll be focusing on my ongoing project(s) about propaganda.

And there are several project ideas that I’d like to implement later. I long for the time when I didn’t have to think about politics so much, and I hope I’ll still get an opportunity to work on something not related to suffering, totalitarianism and violence.

And I’ll try to use any chance to talk about Belarus and spread the word about us as long as I can.

— –

And here are some words about my Instagram work:

Ivan Burakin, Труба ЦЭЦ, г. Баранавічы (@chimney_baranavichy)

Труба ЦЭЦ, г. Баранавічы (@chimney_baranavichy) • Instagram photos and videos

Here, I’m documenting how the regime is literally fighting chimneys. It marks the classic white-and-red colours of power plant chimneys in different cities with red-and-green stripes, which are symbolic of today’s Belarusian national flag. The white-red-white flag is our historical flag, which is now banned by the regime. You can get arrested for a combination of these two colours in your clothing or shoes, for a red stripe on your white car (which was manufactured that way), or if you hang your red pants among white shirts on your balcony. These are real cases. And there are many other, not less absurd, cases too. I’ve been “waiting” (and taking pictures) for three years after the 2020 protests for the regime to paint the chimney in Baranavichy. They did it in August 2023. The first part of this spontaneous project was thus finished. Now I continue to photograph it, waiting for the fall of the regime in Belarus, which will be the official end of this project.

Баранавічы (@baranavichy_) • Instagram photos and videos

Here I’m documenting space, which not many people want to document. I’m taking pictures of my hometown, which is not a beautiful place, and that’s why it’s not photographed often.

I started the page hoping to inspire people to share old pictures of the city from their private analogue albums because I was looking for a picture of a very particular place, which I remember from my childhood but which doesn’t exist anymore. I haven’t yet found such a picture, but at some point I realized that the pictures I take today will be interesting to those who are 5–10 years old now.

Because even though the city is not huge, it changes, and I’m trying to document those changes.

It’s not an “artistic” project but rather a meditation. And it’s also a try to show that there is not only Minsk in Belarus but other places too. Not all of them are nice or worth visiting, but they exist, and the majority of our population lives in those kinds of cities and towns, not in Minsk.

Ivan Burakin, Belarus from above (@aerials_by)

Belarus from above (@aerials_by) • Instagram photos and videos

Here you’ll find pictures taken by a drone. No stunning views, no fantastic editing.

Mostly churches and other tourist attractions, although I’m also trying to take pictures of something that is not often photographed. It might be interesting for those who have no idea what Belarus looks like. Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, the Belarusian regime has been introducing ever more regulations and restrictions regarding drones. At the end (that is, September 2023), they just prohibited using or possessing drones at all.

Могілкі Беларусі (@cimetiere_belarus) • Instagram photos and videos

Belarusian cemeteries. It all started with the project Pre-Mortem and then I just continued to visit different cemeteries and take pictures there. There is no message behind it, just a typology of graves, gravestones and grave inscriptions in Belarus. No witchy-emo-necro stuff or fancy editing, either.

Thanks Ivan!