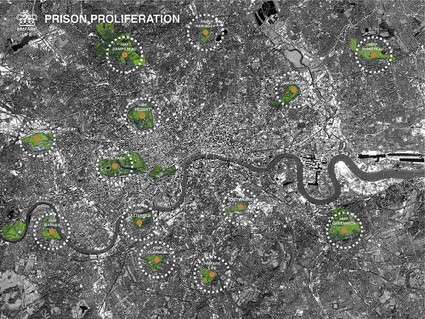

Alexander Kalli‘s graduation project for the Architecture department ADS3 at the Royal College of Art offers a provocative reflection on the punishment system in the UK.

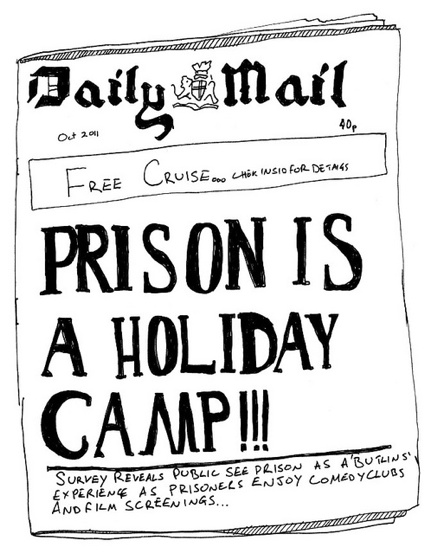

HMPark Life was triggered by the reaction to last Summer’s England Riots: the public wanted to see the looters severely punished, courts were advised to hand out tough sentences, the Daily Mail suggested that incarceration might not be enough since -they wrote- prisons are little more than ‘holiday camps’ and the government stepped in with the proposal to subject inmates to 40-hour working weeks.

HMPark Life is a radically new type of prison that would be built in the middle of London. The project questions this drive to turn a prison population into a cheap labour force – one that works not just to provide skills to inmates in the name of ‘rehabilitation’ but forces offenders to be both visibly productive and punished to quench the public’s ever-present blood thirst for justice.

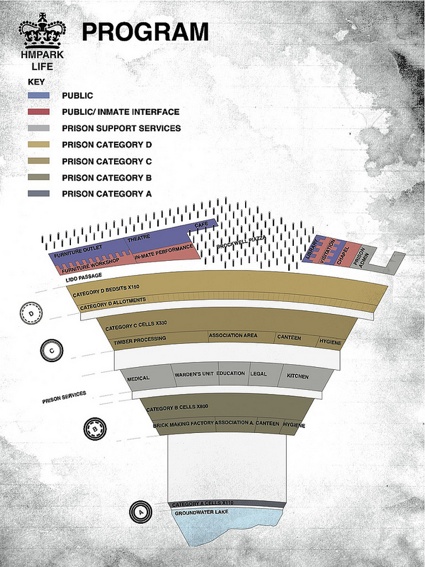

The prison is modeled on the concentric circles of Hell in Dante’s Inferno: the higher the offense, the harsher the punishment and the deeper within the Earth the sinner is sent.

Prison Canyon Section. Courtesy Alexander Kalli

Prison Canyon Section. Courtesy Alexander Kalli

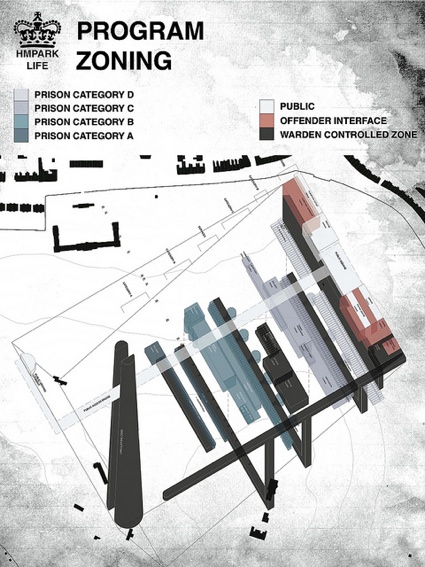

At HMPark Life, the gradation of current UK prison security categories reflect this gradual increase in offense and need for security. The architecture of the prison pushes the analogy even further: it is built deep into the ground, with the most dangerous offenders finding themselves at the bottom of the structure. But the project also introduces an element of spectacle with the possibility for the public to come during their leisure time and gape at the prisoners.

With high security at the deepest point climbing up to an open prison at the surface of the offender-made canyon, this seeping of the prison into the well-healed high street of Herne Hill provides moments of inmate / outsider interaction in the form of a theatre, library and workshops. A public viewing platform perched on the prison main’s circulation core provides an ideal point from which to survey the throng of productive inmates, leaving the public with the sense of satisfaction. This is the new panopticon.

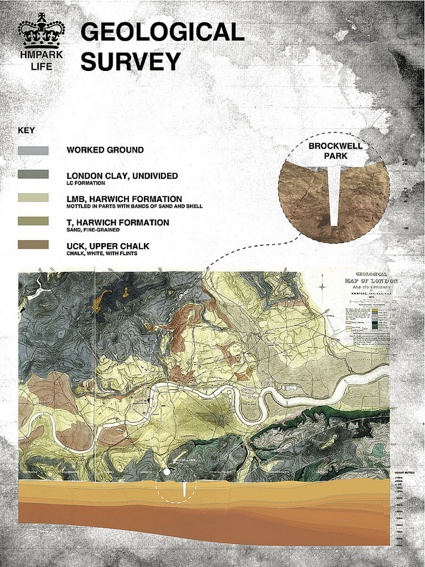

Geological survey. Courtesy Alexander Kalli

Geological survey. Courtesy Alexander Kalli

I had to interview the young architect who brought Dante Alighieri and the Daily Mail in such close contact:

Hi Alexis! The project seems to be a reaction to last year’s riots. Did any other event, piece of news, aspect of social or political life inspire the project?

While writing my dissertation, investigating the physical implications of Michel Foucault’s ‘Heterotopias‘, which are a series of principles that define the nature of what creates deviant/ synchronised/ paradoxical/ time based/ exclusive or inclusive and illusory spaces; I came across the essay Simulacra and Simulation by Jean Baudrillard with the statement,

“The simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth – it is the truth which conceals that there is none. The simulacrum is true.”

As a Londoner, watching the riots unfold on the rolling news from the safety of my suburban family home. I was not only astonished at the randomness of the violence, but also the erratic reactions to it. Passers-by, “social commentators”, politicians, all had their own over-simplified and unsurprising takes on the events blaming education, the benefits system, bankers’ bonuses and the X Factor. But as statistics started to emerge that a majority of the perpetrators had previous criminal convictions, everybody knew there was going to be some kind of reactionary policy making by the Conservative lead coalition Government. I didn’t have to wait long.

The Justice Secretary Kenneth Clarke announced less than a month after the events sweeping changes to the way offenders were to be reformed in Prisons. The phrases “providing skills”, “rehabilitation through purposeful work” several weeks later turned into “offenders shall ‘earn their keep'”. Working a full 40hr week doing menial tasks like laundry or gluing light bulbs together and getting paid up to £10 per week.

This apparent confusion over the purpose of skilling-up offenders or work as punishment is what inspired me to create HMPark Life. Rehabilitation was no longer for the benefit of the offender, but was a tool for the state to either reassure the liberal section of society that offenders were being offered skills to better themselves and the more conservative amongst us that offenders were being put to work as punishment.

To me this resonated with the Jean Baudrillard quote. With this new legislation what was now the purpose of being locked-up? HMPark Life is the state’s cover up that conceals the truth that it has no vision for the purpose of incarceration, only to appease the public.

Photo courtesy Alexander Kalli

Photo courtesy Alexander Kalli

Could you describe exactly how HMPark Life works? Its structure/architecture? In particular Dante’s Inferno and the circles of Hell.

Dante’s Inferno, the first part to the epic poem ‘The Divine Comedy’ acted not just as an allegory for the horrors and turmoils of hell but also for its clear programatic and spatial organisation. Throughout history there have been many versions of diagrams explaining the descending rings of hell and all follow the poem’s stepped, conical canyon description bellow the surface of the earth, with Lucifer and a frozen lake at its deepest point. The lower you descend the more heinous the sin one had committed. This logic seemed appropriate for a prison.

UK prisons are divided into 7 different security categories, 4 specifically for adult males. Category A is the Highest security for those who pose the most risk to the state and public, B is for those who still pose a risk to the public but also is where remand prisoners are sent (those awaiting trial or sentencing), C is for offenders who cannot quite be trusted in an open prison and D is open conditions. This security gradient fitted easily with the Inferno and so by placing the highest security (greatest sin) at the base of HMPark Life with B, C, on levels ascending with the Open category D on the surface it gave the project a clear structure. From then on the rules were to keep the ‘enlightened’ programs such as the library/ visitors’ centre and theatre on the surface and more arduous menial tasks such as furniture making or clay pit digging for those in the descending levels.

Prisoners’ circulation is always on the surface of the building to offer a full view to public onlookers while wardens are hidden in a warren of tunnels running behind the main structure. Everything in the prison is made out of bricks manufactured on site as part of the category B punishment. The idea being that the arc segment of prison would one day complete itself into a full circle. Cells have different sized window openings depending on the level of punishment while those at the very bottom live in hollowed out caves, barely above the water table. The architecture is borne out of a need to maintain secure barriers between each level and for the structure to securely hold back the earth. The building therefore becomes the surface of the canyon face.

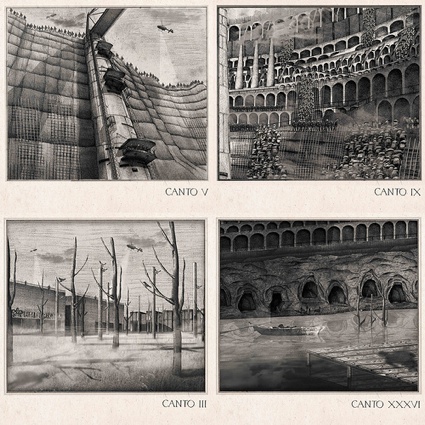

Dante’s Inferno also worked as a way of planning the views to depict parts of the project. The poem is divided into 34 Cantos or chapters, each describing Dante’s journey further into the depths. The Canto numbers on the views relate to the points within the poem that are identical to parts of the prison; for example Canto III describes the ‘Lost forest’ and the entrance to Hell, which in HMPark Life has become a woodland littered with trees disguising columns and the library/ visitor centre. Some of which function as light funnels for the prison workshops bellow and provide perches for CCTV cameras. Canto IX is the point at which Dante looks back at where he had come from, Canto V is where judgement of sins are passed deciding on the level of inferno, so here I show the public observation tower. Canto XXXIV is the lowest point depicting the worst sinners’ accommodation with cells of category A.

Photo courtesy Alexander Kalli

Photo courtesy Alexander Kalli

Photo courtesy Alexander Kalli

Photo courtesy Alexander Kalli

Why did you locate the prison in Brockwell Park?

Brockwell Park is just south of Brixton, where some of the worst rioting occurred. It acts as a barrier between the affluent neighbourhood of Herne Hill to the East and a large council estate to the West and contains the must have pleasant park facilities such as a restored 1920’s lido, an organic community garden and tennis courts. It is also half a mile from the existing HMP Brixton.

During my Research I discovered HMP Brixton to be the worst in terms of the Prison system’s own ratings. No outdoor space, offenders spend up to 23hrs a day in their cells designed for one in the 19thC but now accommodating up to 4, unsanitary conditions, rat infested and the building is Grade II* listed so updating the facilities is bizarrely out of the question. By placing the prison in the park I’m merely following current legislation to its extreme.

“Prisons should be built within close proximity to communities in order to form close links and aid integrating offenders back into the community” planning guidelines state.

London’s inner city prisons such as Pentonville and Brixton occur in the midst of residential areas, behind high walls barely sign posted they almost disappear into the urban fabric. It was important to the project that opportunities were borne out of program conflicts with the context: Pleasure/ Punishment, Play/ Work, Freedom/ Enclosure.

Finally with prisons being so over crowded, and London’s prisons lacking in the legally required space then London’s parks become an ideal site, especially since the prison is to be our prison and become part of our leisure time experience.

Image courtesy Alexander Kalli

Image courtesy Alexander Kalli

Also i was wondering about the kind of people who would want to watch the inmates working. I suspect, like you probably did, that among them we’d find mostly readers of the Daily Mail. In my view, most readers of the DM are far more dangerous than prisoners. So what would protect the inmates from the public?

I did draw a lot of inspiration from the Daily Mail. It is always useful to look at something so opposed to your own opinions in order to draw something out of yourself. The headline “Prison is a Holiday Camp” popped up a few times in the Daily Mail, citing inmates’ ability to access TV (for a fee) and table football. Though if you asked the inmates of HMP Brixton i’m sure their opinions would differ.

HMPark Life does not respect the inmates rights to a decent level of privacy. At the central point to the prisons arc is a public viewing tower. In Jeremy Bentham‘s ‘Panopitcon’ the institution, or prison warden lie at the centre of the plan, with uninterrupted views of the prisoners’ cells. The point being the architecture creates the constant feeling of being under observation without a warden needing to be there. HMPark Life places the public at the centre of this new panopticon.

There is a viewing platform for each level of security as you descend the tower. I imagined the more casual park passer by might take their children as a warning for misbehaving and perhaps the lower one goes you might come across characters like Jeremy Kyle, or a demonstration by ‘Parents Against Pedophiles’. Now i’m thinking Gordon Ramsay would happily sit there with the Daily Mail crowd. I caught 5 minutes of his new series where he’s getting some inmates of HMP Brixton to make fairy cakes, when I heard the tagline “Gordon Ramsay thinks it’s time Britain’s prisoners paid their way.” I had to switch it off. For a man arrested for ‘gross indecency’ in a male public toilet you’d think he’d want to distance himself from this issue of public humiliation as a form of punishment, unless this is a long overdue part of his community service.

Photo courtesy Alexander Kalli

Photo courtesy Alexander Kalli

HMPark Life would host different categories of prisoners. Do they mirror the already existing categories?

The categories of prison exist already. But only in a few instances do prisons of differing categories occur on the same site and they never share facilities. For example, Belmarsh Prison (Category A) is the UK’s highest security Prison where those charged (or not quite charged) of terrorism are held. But next door is a male juvenile detention centre.

HMPark Life layers these categories from D – Open conditions occurring on its surface to A – High security housed in the bottom of the canyon.

Lina Bo Bardi, Sesc Pompeia (image manystuff)

Lina Bo Bardi, Sesc Pompeia (image manystuff)

Finally, i had a look into the publication that accompanied the exhibition at RCA. One of the chapter is “precedency study” and it features works by Herzog & de Meuron, Lina Bo Bardi’s Sesc Pompeia, the prisons of Piranesi. Could you explain briefly how you draw inspiration from them?

References are important in trying to develop a language that informs the project whilst at the same time being sympathetic to the way I like to draw and depict. CaixaForum Madrid by Herzog & de Meuron was mainly a formal reference. The perforations and it’s ‘cragginess’ being conducive in a way to design the caged exercise spaces of the inmates, with differing perforation densities in accordance to the level of punishment/ prison category. In Lina Bo Bardi‘s amazing Sesc Pompeia in Sao Paulo I was looking at the system of exposed circulation and the ruthlessly efficient series of walkways that jut between its two monolithic towers. The most immediately obvious precedence I drew from was Piranesi’s Carceri d’invenzione (imaginary prisons) etchings. HMPark Life’s 4 ‘Cantos’ used the same techniques of awkward angled view points and constricting the image inside the frame as well as a disorientating sense of scale. In Piranesi’s etchings it is quite hard to judge how big this world is until he places a crumpled figure somewhere in the foreground.

Thanks Alexis!