Half Lives: The Unlikely History of Radium by Lucy Jane Santos.

Publisher Icon Books writes: Of all the radioactive elements discovered at the end of the 19th century, it was radium that became the focus of both public fascination and entrepreneurial zeal.

Publisher Icon Books writes: Of all the radioactive elements discovered at the end of the 19th century, it was radium that became the focus of both public fascination and entrepreneurial zeal.

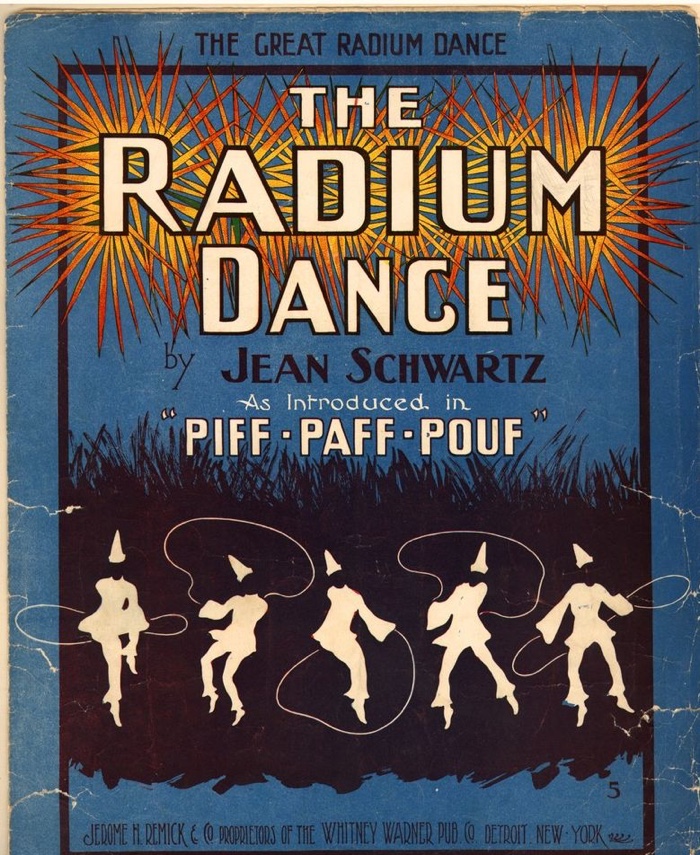

Half Lives tells the fascinating, curious, sometimes macabre story of the element through its ascendance as a desirable item – a present for a queen, a prize in a treasure hunt, a glow-in- the-dark dance costume – to its role as a supposed cure-all in everyday 20th-century life, when medical practitioners and business people (reputable and otherwise) devised ingenious ways of commodifying the new wonder element, and enthusiastic customers welcomed their radioactive wares into their homes.

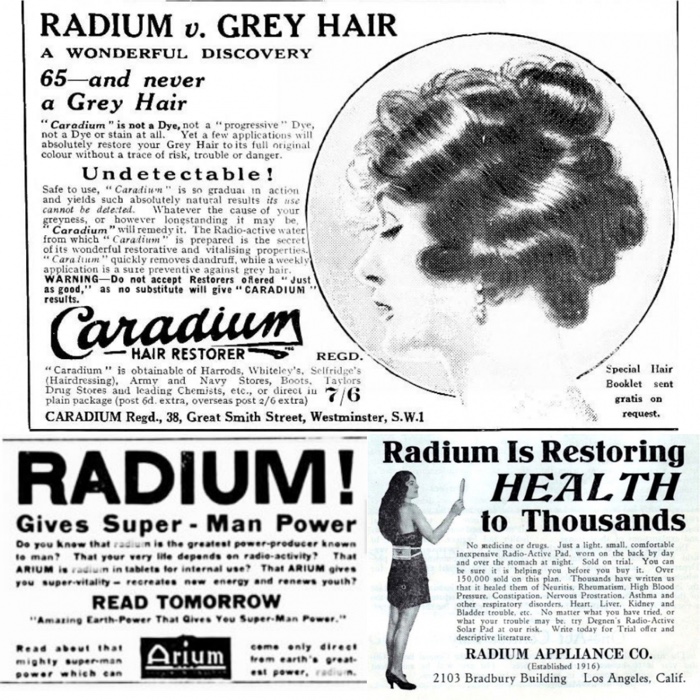

Shortly after radium was isolated, an atmosphere of enthusiasm and inventiveness took over Europe and the U.S. It was the early 1900s, radioactivity was revered, radium was celebrated in poems. Scientists, medical practitioners and entrepreneurs -some well-meaning other totally unscrupulous- launched treatments and products that now sound hysterically dangerous. Radium could do anything. It could enhance sexual virility and conquer baldness. It was in condoms, toothpaste, corsets, hair tonics, infant food, creams that gave you a glowing complexion, products that provided “abundant physical fitness” (whatever that meant) and fluids that promised to cure cancer “in all forms, locations and stages.” In the early 20th century, New Yorkers could even buy golf balls filled with radioactive materials that ensured a “high degree radiant energy” and a longer ball fly (the idea of radioactive golf balls was resurrected the 1950s with atomic golf balls that were easy to locate with the help of a Geiger counter.)

I’m particularly fond of William Thomas Green Morton’s early 20th century “liquid sunshine therapy” which combined radium, water and light, a distant precursor of Trump’s light and disinfectant coronavirus treatment.

Radithor, an early “energy drink” containing radioactive radium. It was advertised as a cure-all medicine for fatigue, arthritis, neuritis and other ailments. John B. Carnett/Bonnier Cor/via Getty Images

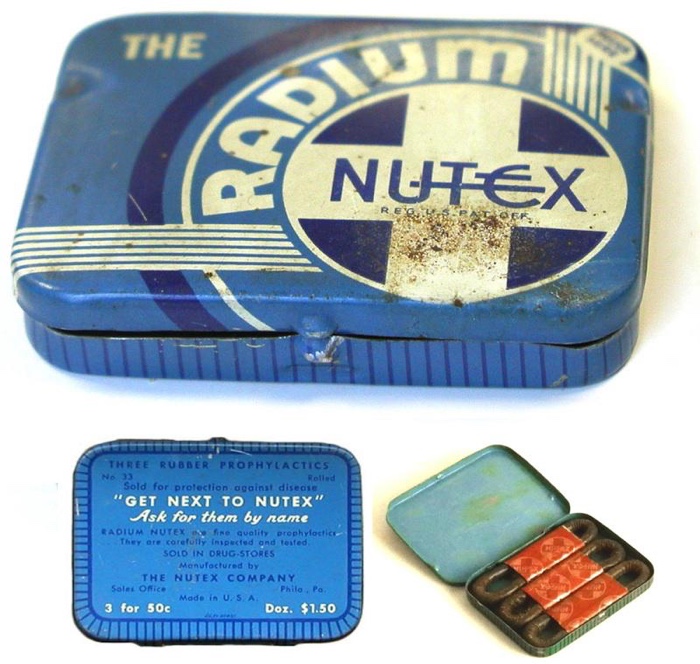

NUTEX Radium Condoms, 1940’s (via)

Most of those quack remedies and bizarre objects were readily available. You could buy them at your local chemist, in department stores or even order them by postal mail. Unsurprisingly, there was no safety regulation regarding the transport of radioactive material. Good thing then that due to the prohibitive cost of radium at the time, most of these products contained neither radium neither any of its weaker derivatives.

The first radon spa in the world opened in 1906 in St Joachimsthal, now Jáchymov in Czech Republic. St Joachimsthal was the number 1 source of radium in the world. And radon, a decay product of radium, was a cheap way to get a bit of that radium magic.

Realising that the water surrounding the mine could be radioactive, the town capitalised on the interest of the use of radium in medical treatments and started promoting its water cures. The Radium Palace Hotel offered treatments using water pumped directly from the mines. Elsewhere in the city, you could buy radium soaps, radium cigars and radium pastries. Other towns across Europe soon followed suit. In Bath, for example, you could drink radioactive water, find radium bread in a bakery and bring home bottled mineral waters.

Radium therapy was hailed as a medical wonder. Scientists experimented on themselves, demonstrating that “if radium could burn or kill skin it could destroy tumours”. Burns from radium healed quickly. It made operations superfluous, eliminated tumours, solved all sorts of dermatological problems, could cure blindness, impotence, arthritis, depression, insanity. A wife-beater was said to have been cured of both cancer and violence. In 1896, some breast cancer patients were being offered a course of 18 x-ray treatments. Unfortunately, neither the doctors nor their patients knew about the long-term damage of repeated or prolonged exposure to radium.

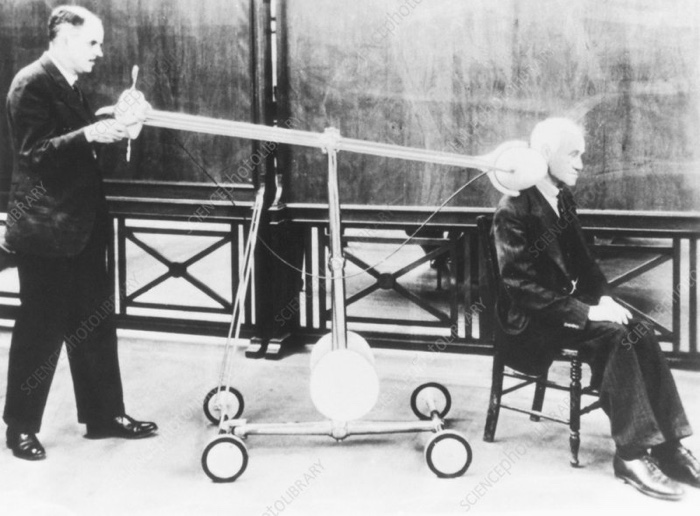

Man with neck cancer receiving radiotherapy treatment from a Flint radium “bomb”, designed in 1934 for four hospitals in London, England. Photo

Caradium Hair Restorer. Photo: Medium

After a series of scandals, a steady stream of dying radiologists, a couple of atomic bombs and efforts by medical associations to warn against quack treatments, radioactivity started becoming a subject of community alarm. It was not immediate in the US which remained enamoured with all things atomic for a while after WWII but science fiction books started featuring irradiated monsters, Hollywood movies began to reflect on the destructive side of the substance, companies closed, fashion changed, medical thought moved on and by the end of 1940s, radioactivity became associated with toxicity.

Half Lives is both joyful and harrowing. Throughout its pages, Lucy Jane Santos gives life to a rich material panorama made of adverts, objects, miracle cures and the interplay between scientific discoveries and popular culture.

In the epilogue, the author explains the many ways that radium is still haunting us. Buildings and production sites associated with radioactive elements are still in use. Their occupants often unaware of the prior use of the edifices. In 2010, The Guardian revealed that portions of the 2012 Olympic park in London built on land used to be occupied by companies producing glow-in-the-dark paint for watches and clocks during WWII.

And low-level radiation still has supporters who believe in its health benefits. Jáchymov, for example, continues to offer radon cures. Elderly people still bathe in the spa waters at Schlema, which contain low levels of radon, convinced that it can cure their rheumatisms. And if you’re not inclined to travel, then you can buy a small bottle of a Radium Bromatum homoeopathic remedy.

And then, of course, there’s the fact that pretty much everything and everyone is naturally radioactive.

More images, objects and facts I discovered in the book:

Women painting alarm clock faces at the Ingersoll factory in January 1932. Known as the “Radium Girls,” these workers were putting their health at risk by lip-pointing the brush and ingesting radioactive radium. Daily Herald Archive/SSPL via Getty Images

By the mid-1920, the popularity of radium was beginning to wane. Glow-in-the-dark wristwatches, however, were still very fashionable. Women hired to paint the faces and dials on glow-in-the-dark wristwatches used their mouth to get a fine point. Because the radium paint was tasteless and odourless, the Radium Girls didn’t suspect how dangerous their job was. Until many of them started suffering from anemia, bone fractures and necrosis of the jaw. Some even died. Amelia Maggia was one of them. When she died in 1922, at 24 years old, her death was attributed to ulcerative stomachitis and syphilis. The U.S. Radium Corporation had insisted that its product was safe. Her body was exhumed in 1927 to be autopsied. Her death was confirmed to be radiation poisoning. Meanwhile, employees were asking for compensation for their medical and dental bills. Many court cases later, the Radium Dial was finally forced to pay compensations.

The scandal of the Radium Girls led to the scientific understanding of the way radium accumulates in organs. It also led to better health and safety standards for workers inside and outside the radium industry. Furthermore, the right of individual workers to sue for damages from corporations due to labor abuse was granted as a result of the case.

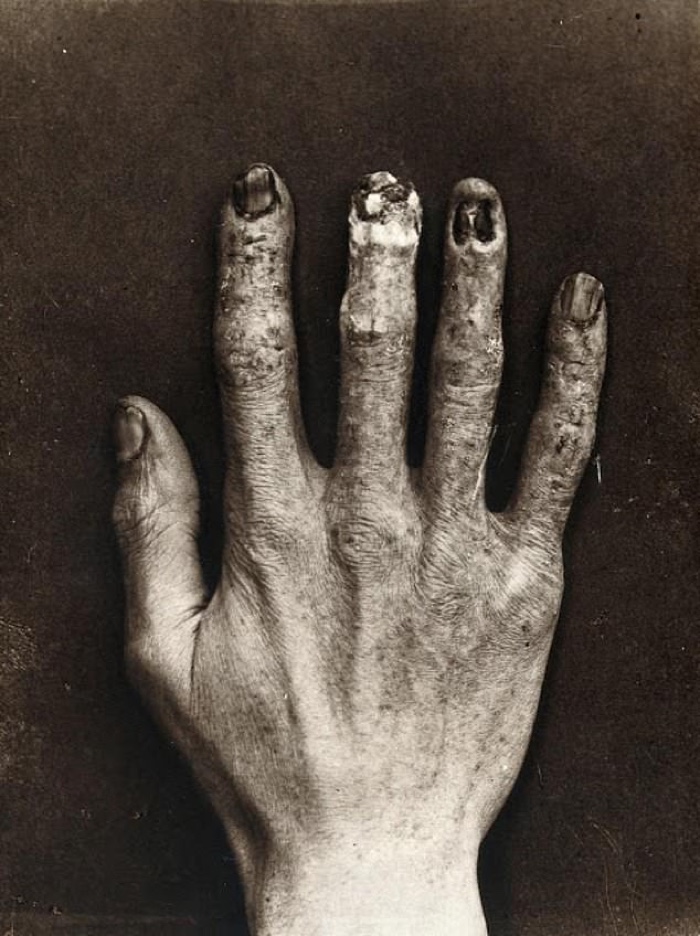

The hand of Clarence Dally, Thomas Edison’s assistant, was covered in lesions after countless hours of intense X-ray radiation experiments. He died of a cancer caused by radiation exposure at the age of 39. Edison wouldn’t have anything to do with it when he realised what happened

Wilhelm Röntgen developed the first X-ray photograph in 1895. As he was experimenting with a cathode tube that emitted different frequencies of electromagnetic energy, the physicist noticed that some appeared to penetrate solid objects and expose sheets of photographic paper. He called the strange rays x-rays and used them to photograph his wife Anna Bertha’s hand. His discovery revolutionised the diagnosis and treatment of injuries and illnesses.

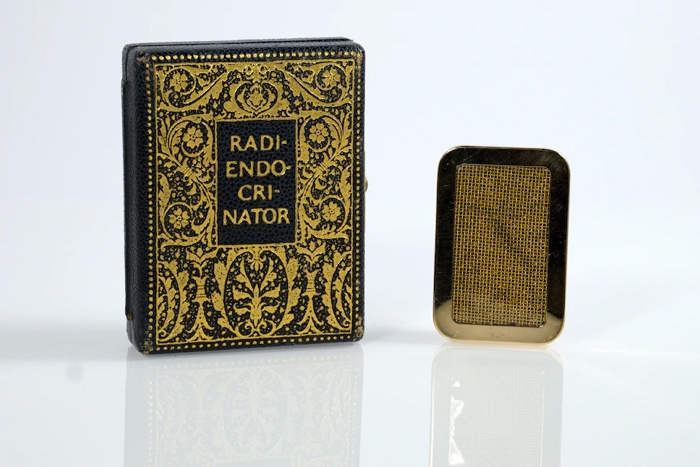

Velvet-lined case of an radiendocrinator, which was intended to be placed in a special jockstrap. Photo: Carl Willis

Marie Skłodowska Curie, the Polish-French chemist discovered both radioactivity and the radioactive elements radium and polonium, achievements that won her two Nobel prizes. Time Life Pictures/The LIFE Picture Collection/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

One of Curie’s mobile units used by the French Army. Bibliothèque nationale de France, département Estampes et photographie (via)

The musical play Piff! Paff! Pouf! on Broadway featured a piece of music called the Radium Dance played in the glow-in-the-dark atmosphere. The production probably used phosphorescent paint rather than the very costly radium. Photo via The Society for Theatre Research