If i were a man i’d want to be either Idris Elba or Garnet Hertz. You know Elba, he was gangster Stringer Bell in The Wire and a detective in Luther. Now Garnet Hertz is neither of that (to my knowledge) but he’s the guy everybody wants to talk to at media art, tech or design conferences because his works play with several levels of engagement: from instant entertainment to deep reflection on DIY culture, design processes and technological progress. Hertz makes robots controlled by cockroaches, video game systems that you can literally drive around, he gives talks about Zombie Media and has just crafted a magazine about critical technical practice and critically-engaged maker culture that puts us all (us being media people) to shame.

And now for a more rigorous bio of the artist:

Doctor Garnet Hertz is a Fulbright Scholar and contemporary artist whose work explores themes of technological progress, innovation, do-it-yourself culture and interdisciplinarity. His work often involves building real-world technologies that are designed to take his audience into a speculative future gone humorously astray. In the process, Hertz’s work inverts the idea that technology needs to be faster, more efficient or higher resolution: innovation is born out of human emotion, historical tradition, and creative obsession.

Hertz is Co-Director of the Values in Design Lab at UC Irvine, is Artist in Residence / Research Scientist in Informatics at UC Irvine and is Faculty in the Media Design Program at Art Center College of Design.

Garnet Hertz, Outrun, Denmark, 2011

Garnet Hertz, Outrun, Denmark, 2011

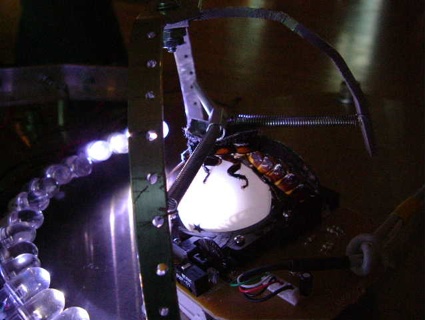

Garnet Hertz, Cockroach-controlled mobile robot. Photo by Sharmanka

Garnet Hertz, Cockroach-controlled mobile robot. Photo by Sharmanka

![]() Garnet Hertz, Videodome

Garnet Hertz, Videodome

Hi Garnet! I’m very intrigued by Videodome. Can you explain us what the experience of using it will be like? Can the person whose head is inside the big helmet move around? What will he or she perceive and how? And is what they see broadcast in any way to a broader audience?

Videodome is a project that I’m developing that explores different types of virtual reality without the use of a computer. Instead of a computer, I’m using a large number of miniature “spy” videocameras connected to many televisions. At this point, the project has two main physical structures: a helmet-like globe containing the cameras and a two meter diameter geodesic dome covered in televisions. These two components will be configured in different ways -with inner-and-outer facing cameras and screens, for example- to creatively explore the process of mediated sensation, perception and reality.

The initial configuration simulates being inside of someone else’s head. To do this, I’ve constructed a wearable panopticon-style helmet – a clear plastic globe with a diameter of 45cm that has 48 cameras that face inward toward the person’s head. Each camera is connected with cables to a flat panel television, and the group of televisions are arranged in a dome with screens facing inward. The screens form a low-tech VR-style cave that show the person’s face turned inside-out.

At this point, this project is local and live with no transmission or recording – it’s goal is to be analog. If I was going to do recordings of the camera array, it might be fun to try to do it with a mountain of VHS VCRs.

A major theme in my work is the exploration of inefficiencies and intentionally doing things the wrong way, and I have a recurring interest in poking fun at virtual reality. I love graceful kludges, rural folk machinery, and chindogu, and building Videodome is like trying to build a realtime immersive imaging system with parts that don’t cost more than $10.

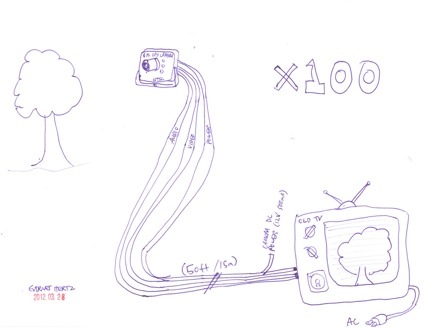

Project Sketch for Videodome

Project Sketch for Videodome

From a technical perspective, the project is a RAID – a redundant array of inexpensive devices – and is easy to reconfigure. It’s just a $10 camera, a cable, and an old television multiplied many times. The cameras can be positioned to face outward on the helmet, or the camera cluster can be put on a dog or a tree – or the televisions can be arranged on a floor, in different shapes or on the side of a building. For me, it’s a return to the spirit of video installation artists like Dan Graham or Nam June Paik when the format of video still had a sense of technological magic.

When my sons (aged 7 and 9) first played with a typewriter, their perception of it is that it was a very fast computer that instantly printed letters as fast as you typed them. And – if you think about it from the perspective of the time it takes between hitting a keystroke and when the letter is rendered on paper – the typewriter beats a supercomputer every time. In a similar way, an analog video camera is like a streaming video server with zero lag – typewriters, analog video cameras and other devices from media history are still very high performance and interactive devices in their own limited ways. The project is aimed at exploiting the high performance component of an old technology – it’s a bit of a novelty at a time where digital cameras are thickly layered in technical infrastructure. You just plug an analog camera and it’s instantly streaming video, although your network is only as long as your video cable.

The project is influenced by a few projects, especially Michael Maranda’s Sphereorama (1991), Kenji Kawakami’s 360′ Panorama Camera (1995), and Hyungkoo Lee’s Objectuals (2002) – and the idea to use a mountain of cheap cameras initially came from my friend Jason Torchinsky. It’s scheduled to premiere in San Jose at an exhibition that Madeline Schwartzman is curating related to her book “See Yourself Sensing”. The piece is not in the book, but I’m very happy the project is included in the show – in my opinion her book is the most brilliant contemporary art books I’ve seen in a long time.

Garnet Hertz, OutRun

Judging by the reaction the project OutRun received in gaming, gadget, vehicle blogs and magazines, have you ever thought of modifying the work and giving it a commercial existence, making it something that rich kids could buy?

The original car is actually for sale, but it’s priced at $100,000 – so it would take a very rich kid to purchase it. I’ve floated the idea of purchasing the original car to a few obscenely rich people like Jay Leno but as of right now it’s still for sale. There was a glimmer of hope when the billionaire owner of Lego, Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, drove the original project in Denmark. He clearly had a lot of fun driving the project – and he had the money to pay to replace anything he crashed into – but I don’t think he thought I was serious when I proposed to trade him for one of his Ferraris.

Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen driving OutRun in Billund, Denmark

Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen driving OutRun in Billund, Denmark

I generally don’t pursue the monetization or commercialization of my projects – I tend to enjoy focusing on research and the exploratory prototyping phases of technological development. At this point I’m comfortably paid to do my artwork, so I’d rather spend my time focusing on building new projects.

That said, if anybody is interested in the original vehicle or working on porting the concept into a more commercially viable platform, I’m open to ideas.

And more generally, have you ever been tempted to work more closely with the gaming industry or any other industry? Surely they’d welcome creative people like you?

I used to work in the design industry through advertising agencies, film production houses, and by doing product prototyping, and at that time my slogan for much that work was “Making Your Shitty Idea a Reality”. There were a few exceptions of situations where you have a blank slate and a blank check that I found enjoyable, but for the most part I’ve found it uninspiring.

There are significant exceptions to this – I think of Julian Bleecker at Nokia for example – I think there’s a lot of room in research positions that might be rewarding. It also may be that most of my experience in industry was in the 1990s when I had a thinner portfolio and CV; maybe there are a lot of places that would be a good fit.

I generally like the quirks of the art world and academia; I usually find my colleagues in these environments to be interesting, intelligent and strange in a fun way. Both of my current appointments – full time at UC Irvine in Informatics and part time at Art Center in Media Design – are great because of the people and the projects they’re working on. Paul Dourish, Gillian Hayes, Don Patterson, Geof Bowker, Anne Burdick, Tim Durfee, Ben Hooker, Chris Csikszentmihalyi and everybody else I work with – they’re all brilliant and fun to be around. And for now I generally get to do whatever I want, so I can’t complain.

![]() Pixel VGA (Version 1, Banff Floor Cluster)

Pixel VGA (Version 1, Banff Floor Cluster)

You wrote in your statement page: “I believe that industry and academia often draw false distinctions between experts and amateurs, hardware and software, mind and body, and science and creativity, and my goal is to meld these polarities in the projects I develop. Many of our greatest social challenges and technological opportunities now lie in these connection points.” How can experts / amateurs connection lead to technological opportunities? Also what can experts learn from amateurs?

I’m interested in leveraging DIY, hackerspace and amateur cultures for a number of reasons. I believe that innovation and breakthroughs happen when individuals go beyond their standard frames of reference and discipline to learn new skills on their own: breakthroughs often require us to become amateurs in a new field, in other words. During the process of learning new things, we often cobble together materials, figure things out informally, and explore things on our own. For this reason, DIY culture and doing things in nonstandard or non-expert ways are useful models for how innovation is done.

I’ve also seen a significant cultural surge toward DIY electronics, physical computing, and hands-on “making” over the last decade. The turn toward physical making is partly due to people being tired of mass produced consumer Walmart culture – they’re tired of having disposable, spiritless and generic junk. DIY electronics is also partially in response against the trend of conceiving information and knowledge as virtual things. Platforms like the Arduino – which started out filling a niche within the physical computing community – has grown to be quite widely implemented in multiple fields of design.

I also think that higher education has become increasingly detached from physical objects. I think that this is a mistake: I believe that innovation and education needs to be engaged with the real world, get dirt under its fingernails, and learn the skill of working hard at problems that are often ambiguous. Universities needs to combine hands-on construction and skill with advanced knowledge and concepts in order to effectively innovate in research – and for workforce development.

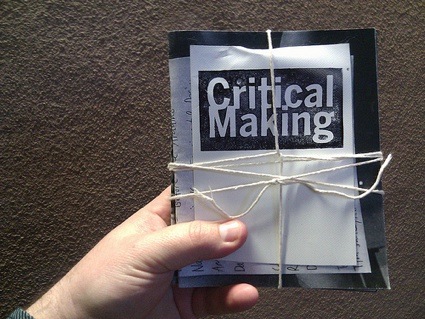

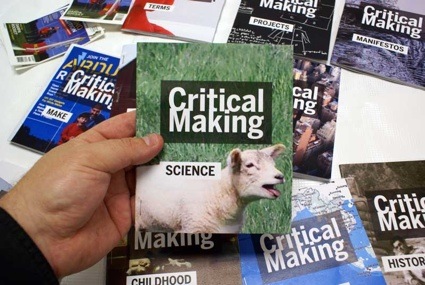

Critical Making

Critical Making

If i understood correctly, the hand-made zine on critically-engaged making were printed in only 300 copies and given out for free. i do suspect that far more than 300 people would love to get their hands on it. Most would even be happy to pay for it. The content is brilliant, so is the format. Are you planning to change the distribution model?

Yes – the project is called Critical Making and I the documentation for the project is at http://conceptlab.com/criticalmaking/. There’s been an outpouring of interest in expanding this project and there are clearly a lot of people involved in DIY or maker communities that don’t fit into the “family-friendly kit-based weekend-project” focus of Make Magazine. The initial idea was to do an actual photocopied zine with a bunch of people I admire and to give it away for free – although this has become a much bigger project with almost 350 pages of content from about 60 contributors. It’s nicely grown into a pack of zines, a little like Ginko Press’s “McLuhan Unbound” project.

I’m still going to give the 300 copies away for free – and I’m making a special edition for the contributors – but I haven’t yet determined what to do after my initial run. I’m currently talking to some different people and presses, and I’m open to ideas.

At this point, I’m not inclined to just slap an open source license on the content and put a PDF of it online. I’d ideally like the project as only available as a photocopied object that somebody hand produced – but I realize that this may not be practical. I’d consider an academic or art press, distributing it through the contributors, or returning to a zine model of people sending cash in an envelope to an address.

There’s an interesting push against electronic books happening – instead of the format of physical books dying, there’s a fresh crop of bookmaking work that fetishizes the physical page. I wouldn’t term it as a “zombification” of books, but a useful opportunity to rethink what physical components of a book are valuable.

For my Critical Making project, if people want copies or are interested in this as a publishing/distribution project, let me know. I’ll send you a copy too, Régine – but the contents of this collection of zines is a whole other conversation… we should talk about it after I’ve shipped them off.

Circuit Bending Workshop, 24 Jan 2010, Art Center

Circuit Bending Workshop, 24 Jan 2010, Art Center

One of my favourite projects on your homepage must be the customized taco (food) truck that would go around communities and give D.I.Y. laboratory for circuit bending. Is it going to happen soon?

This project, with an official title of Repurposing Obsolescence: Teaching DIY Science, Technology and Engineering Practices to Adolescents in Underserved Communities, will design, develop and test Do-It-Yourself (DIY) hands-on workshops to introduce and teach middle school kids in underserved communities technology and design by customizing and repurposing e-waste technology, like old electronic toys. Right now the major outcome of the project will be the creation of a workshop kit that covers the processes of learning DIY electronics for distribution to after school programs and other informal educational venues.

My team has implemented a number of pilot projects over the last three years that demonstrate the ability of hands-on DIY electronics curricula to motivate and encourage students and to enable them to acquire a deeper understanding of core engineering, mathematics and science concepts by introducing creative and artistic use of circuit bending,ì the creative short circuiting of electronic devices that make sound.

I’m interested in extending maker culture into different environments, and I think the approach is useful in getting kids interested in learning about how things work. In this project, I’m particularly interested in reaching out to communities that normally wouldn’t have the resources in their schools to explore art or electronics. Sadly, California has a growing list of schools that have slashed art or any items that aren’t part of the standardized test structure. Hands-on education – with shop, woodworking and art classes – have been removed from most schools. This is doing an incredible disservice to kids, and it’s especially bad in communities that don’t have a lot of resources. It’s not teaching people how to think, be creative or holistic problem solving – it’s teaching people how to memorize things to get a high score on a test.

I think circuit bending is a great antithesis to a standardized test. It doesn’t have one right answer. It uses your hands. It makes noise and can be dangerous. It can be very simple or incredibly complicated. It involves genuine exploration and discovery. In a nutshell, I think it’s a better model for how life works than a test on paper, and I think the United States would be a better place and have a more skilled and creative workforce (and more interesting artwork) if more kids were taught things like circuit bending at an early age. The scientific hypothesis of the project is that this approach will lower barriers to experimenting with custom-built electronic instruments and lead to greater participation and success of people pursuing secondary education.

So, my challenge in this project is to develop hands-on workshops, kits and curriculum that work within the educational system of the United States, or at least Southern California. I also want it to work for people with English as a second language, and as a result have translated prototypes of the curriculum into Spanish, Chinese, Korean and French – but within Southern California, Spanish is my main focus.

My vision is to extend this work through the development of a mobile D.I.Y. laboratory to more easily bring our specialized infrastructure to underserved communities. In other words, have a vehicle that acts as a “bookmobile” to bring specialized resources to groups and communities that lack educational infrastructure. The initial idea for this “makermobile” would be to have it in the form of a customized taco (food) truck, a common component of Los Angeles and Orange County culture. This vehicle would transport workshop mentors and specialized tools and would serve as a public platform to disseminate the workshop materials. I’ve envisioned that the vehicle would need to be really cool – with lowrider hydraulic suspension, nice rims, and a cool paint job – as a form of propaganda to get kids excited.

I’ve recently got funding to develop the curriculum and hardware component of this project, but I don’t yet have funding to buy a vehicle. As it turns out, purchasing a vehicle through a university or research funds is usually problematic – it doesn’t fit into the standard categories of research equipment, especially a pimped out lowrider taco truck.

Garnet Hertz, Experiments in Galvanism, 2003. Photo by Bill Eakin, as installed in Ace Art Inc, Winnipeg, Canada

Garnet Hertz, Experiments in Galvanism, 2003. Photo by Bill Eakin, as installed in Ace Art Inc, Winnipeg, Canada

Do you think schools, and education in general, isn’t doing enough to make young people ‘techno-literate’?

I think kids generally get quite a bit of informal education around technology using computers, mobile phones or iPads at home. What they’re missing is the opportunities to open up and learn about the mechanics of what’s inside of the black boxes of technology, to go beyond a consumer of the technology. I want kids to move beyond downloading a game off of the Apple App Store – that’s not technical literacy, it’s just another format of consumption.

Toy Hacking: Verano After School Program, March 2011. Photo by Silvia Lindtner

Toy Hacking: Verano After School Program, March 2011. Photo by Silvia Lindtner

You are Co-Director of the Values in Design Lab at UC Irvine with Geof Bowker, Cory Knobel and Judith Gregory. The objective of the lab is to blend “rich social theory with design practice in order to produce information systems and technology imbued with strong social and ethical values.” Which kind of works are you developing in the Lab? Do you have some examples of projects that represent particularly well what the students are working on there?

Actually, within the last couple weeks this lab name has changed to “EVOKE” – Emerging Values, Ontologies, and Knowledge Expression – we’re working on a number of different things, including a Values in Design workshop for doctoral students.

At this point we’re still getting the lab set up, but we’re interested in infrastructure, ontologies, values, big data, making, and how knowledge is formed and communicated. It’s an intentionally big mix of topics that doesn’t neatly fit into the format of something like a TED talk. I see the lab like a research group or design initiative, perhaps like a smaller version of the MIT Media Lab, that work on investigating complex issues, building prototypes and solving problems built on a foundation of serious social theory.

We have a lot of projects going on, including researching new forms of scholarship that move beyond linear texts, design by youth, and work that encompasses biomedical informatics. The first project that we completed at UC Irvine during summer 2012 was a design workshop for doctoral students, titled “Values in Design”. Our mission in this project was to train researchers in a broad range of disciplines – including Informatics, Computer Science, Design and Science and Technology Studies – to produce new forms of information systems and technologies which express strong social and ethical values. It ran over the course of a week, and the format was a little bit like Project Runway – with teams designing technology prototypes – and an academic conference with guest speakers lecturing on design-oriented topics. It was a lot of fun.

Within the different projects through EVOKE, I’m primarily interested in making physical prototypes of complex concepts: I’m focused on what art can do to actually extend and add to research and science.

Garnet Hertz, Doom at Catalyst Arts (Belfast, UK), 2012

Garnet Hertz, Doom at Catalyst Arts (Belfast, UK), 2012

Garnet Hertz, Doom at Catalyst Arts (Belfast, UK), 2012

Garnet Hertz, Doom at Catalyst Arts (Belfast, UK), 2012

I hope you won’t mind if i say this but you’re an established artist. You’re also teaching and holding academic positions. Could you point us to young, emerging artists whose work we should be paying more attention to? Either students or yours or just people whose work you stumbled upon online or at a Dorkbot meeting?

I have some student work that I’m very proud of, especially my graduate students coming out of Media Design Practices at Art Center. My favorite projects over the last little while are:

– Chiao Wei Ho, Slow Letter (2012). “The design of Slow Letter is based on the concept of Process-based Interaction which focuses on the process instead of the task itself. It is my challenge to the instantaneous interaction of user-centered design. It questions the essentiality of instantaneity and convenience in current digital service. What would the interaction be like when time and space are being elongated? We all have experienced the satisfaction of these digital devices around us, it can take us from point A to point B within no time. However, Slow Letter tends to discover alternative values outside of task-orientated interactions. The project reevaluates the weight of our words in the digital communication by elongates the process between point A to point B. It transforms instantaneity into emotional values and inject unconventional perspectives into the numbed daily routine.”

Chiao Wei Ho, Slow Letter

– Alex Braidwood: Noisolation Headphones (2011). You’ve written about these at http://we-make-money-not-art.com/archives/2011/10/the-noisolation-headphones.php – since you wrote that article an updated video of the project is here:

Noisolation Headphones. Video by Mae Ryan

– Hyun Ju Yang: Measurement of Existence (2010). “This hypothetical device informs your quantum state within innumerable versions of our universe in the quantum state of the universe. The main idea is inspired by an equation, the measurement of existence from the relative quantum mechanics created by physicist, Everett who invented Many-World theory.”

Hyun Ju Yang, Measurement of Existence

Hyun Ju Yang, Measurement of Existence

Thanks Garnet!