Floppy Disk Fever. The Curious Afterlives of a Flexible Medium explores the curious afterlives of the floppy disk in the twenty-first century by interviewing those involved with the medium today. It was edited by artist, musician and researcher Niek Hilkmann and graphic designer and researcher Thomas Walskaar. Published by Onomatopee.

Like many people, I had assumed that the habit of storing data inside a small-ish beige or black plastic square was long dead. I vaguely remember a time when they were glued to tech magazines but that’s about it. Floppy Disk Fever, however, demonstrates that the presence of the obsolete medium in contemporary culture is ensured by a surprisingly large community of enthusiasts, amateurs, artists and academics.

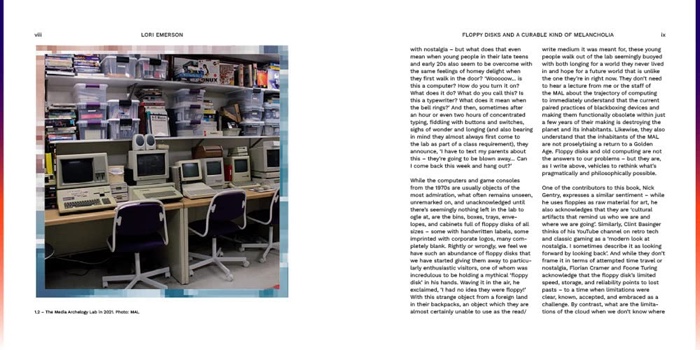

The book opens with an essay about the potential hazards and productive possibilities of nostalgia. Its author is Lori Emerson, an Associate Professor in the English Department and Director of the Intermedia Arts, Writing, and Performance Program at the University of Colorado at Boulder as well as the Founding Director of the Media Archaeology Lab. That’s the last time you’ll read from a woman in Floppy Disk Fever. The editors of the book acknowledge that floppy disk enthusiasts come from various backgrounds but that the vast majority of them are men from Europe and the US. It was thus challenging to reflect the full spectrum of humanity in a publication dedicated to floppy fervour.

Even though there is a man-cave vibe in these interviews, they are not about nostalgia, retro kitsch and ageing geekery. They are also about the contemporary world and the dematerialisation of most of our interactions with computing.

Floppies waiting to be shipped to customers of Floppydisk.com. Image via Teknofilo

Niek Hilkmann, the main editor of the book, organises floppy-centred events as part of the Floppy Totaal festival in Rotterdam. That is where he first got in contact with many of the people interviewed in this book. They are museum founders, archivists, artists, academics and amateurs and Hilkmann gets them to talk about the contemporary use and creative repurposing of the object.

The three most interesting interviews for me are the ones with Tom Persky, Florian Cramer and Adam Frankiewicz.

Tom Persky, the founder of floppydisk.com, a company dedicated to selling and recycling floppies, discusses the challenges of running his business in the 2020s. That is where i learnt that some medical equipment still requires floppies to function.

Florian Cramer, a research professor at the Willem de Kooning Academy and Piet Zwart Institute, has been developing measures of extreme compression in order to squeeze entire movies onto the 1.44 MB of floppy disks since 2009. In the interview, he talks about his interest in working with constraints and why his work with floppies shatters the myth that digital technology is virtual and dematerialised.

Adam Frankiewicz is a theatre director and electronic music composer who founded an independent record label Pionierska Records in 2014 which publishes music exclusively on floppy disks.

Other floppy fans include Clint Basinger who creates content with obsolete tech on the Lazy Game Review YouTube channel; Nick Gentry who uses floppies and other obsolete media as raw material for art; Foone Turing, a media collector and hacker who curated an exhibition on floppies at the Computer History Museum in Fountain View; Jason Curtis, a writer, librarian and collector who founded the Museum of Obsolete Media in 2006; Bart van den Akker, the founder of the Home Computer Museum; Jason Scott, archivist at Internet Archive, filmmaker, performer and historian of tech.

They talk about their relationship with the demoscene and with retro culture, the disappearance of physical media, making money from obsolete tech, going through the hassle of combining old and new tech, the appeal of “failed” formats, the interplay about old and new, online and offline, media archaeology, their importance as cultural artefacts, etc.

Reading the interviews didn’t turn me into a floppy aficionado but i could see the point of longing for a time when you could manipulate technology and see how it worked.

P.S.: I discovered 2 words in the book and looking at them online sucked me into a vortex of fascinating stories and anecdotes. The first one is Sneakernet, the transfer of electronic information by physically moving media (such as floppy disks or USB flash drives) rather than transmitting it over a computer network. The second is skeuomorphs, a derivative object that retains ornamental design cues from their real-world counterparts. The trash bin icon on your computer, for example.