Mauser and Bullet, 1938

Mauser and Bullet, 1938

The Michael Hoppen Gallery has just opened an exhibition featuring a selection of vintage prints by Dr. Harold Edgerton, a photographer whose works are found hanging in art museums and galleries across the world. He even won an Oscar with his short film Quicker ‘n a Wink. Yet, Edgerton was adamant that he was a scientist, not an artist.

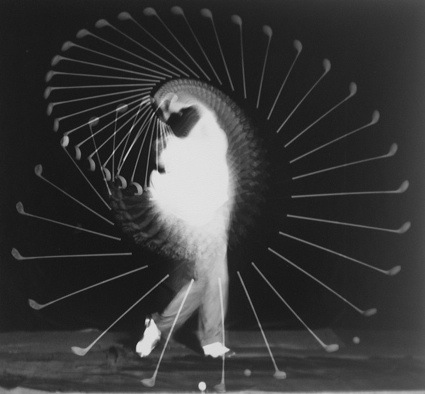

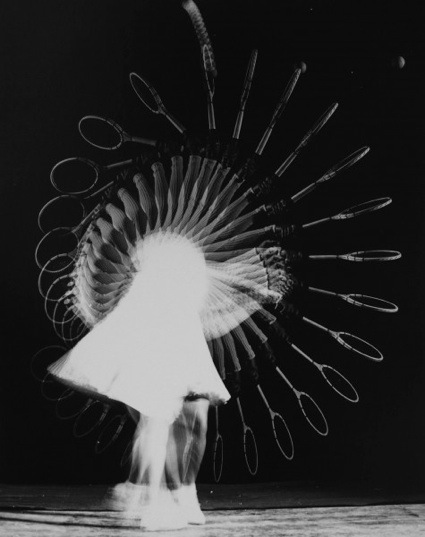

The professor of electrical engineering at MIT invented the ultra-high-speed and stop-action photography when he synchronized strobe flashes with the motion being examined, then took a series of photos through an open shutter that could flash up to 120 times a second. The invention enabled him to photograph motion that was too fast to be captured by the naked eye: balloons at various stages of bursting, bullets tearing through fruits, divers rotating through the air, devil sticks in action, an egg hitting a fan, drops of milk coming into contact with liquid, etc.

If that were not enough, Edgerton was also involved in the development of sonar and deep-sea photography, and his equipment was used by marine biologist Jacques-Yves Cousteau to scan the sea floor for shipwrecks. Or for the Loch Ness monster.

During the Second World War, he pioneered superpowered flash for aerial photography used to create night time reconnaissance images, revealing the absence of German forces at key strategic points just prior to the Allied attack on June 6, 1944.

Bobby Jones, Golf Multiflash (Iron), 1938

Bobby Jones, Golf Multiflash (Iron), 1938

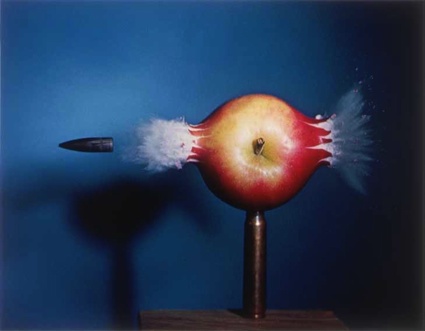

.30 Bullet through Apple, 1964

.30 Bullet through Apple, 1964

To trigger the flash at the right moment, a microphone, placed a little before the apple, pickes up the sound from the rifle shot, relays it through an electronic delay circuit, and then fires the microflash (via.)

Moments after the apple was pierced by the bullet, it disintegrated completely.

Bullet through a Helium Bubble

Bullet through a Helium Bubble

Bullet through King, 1964

Bullet through King, 1964

A .30 caliber bullet, traveling 2,800 feet per second, requires an exposure of less than 1/1,000,000 of a second. Edgerton turned the card sideways and the rifling of the barrel caused the rotation of the projectile, which, in turn, carved out the S-shaped slice of card between the two halves (via.)

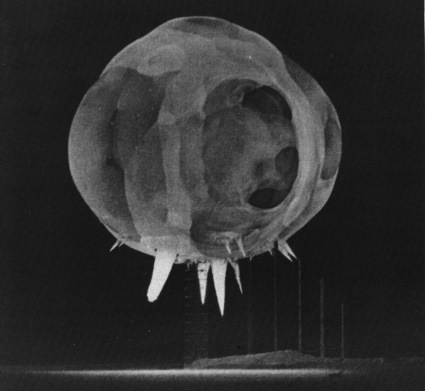

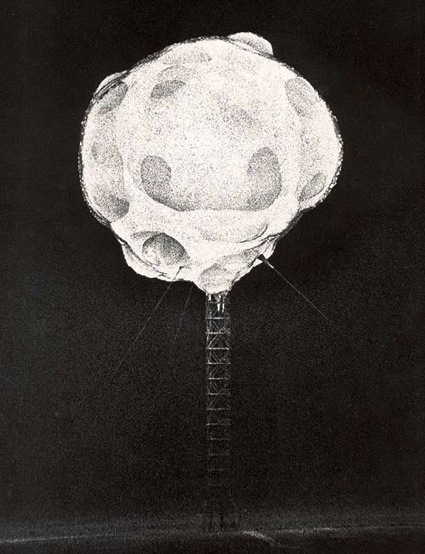

Atomic Bomb Explosion, circa 1952 (more images)

Atomic Bomb Explosion, circa 1952 (more images)

After World War II, the Atomic Energy Commission contracted Edgerton and two of his former students to photograph atomic bombs as they exploded. The trio developed the rapatronic (for Rapid Action Electronic) shutter, a shutter with no moving parts that could be opened and closed by turning a magnetic field on and off.

Revealing the anatomy of the first microseconds of an atomic explosion, the fireball was documented in a 1/100,000,000-of-a-second exposure, taken from seven miles away with a lens ten feet long. The intense heat vaporized the steel tower and turned the desert sand to glass (via.)

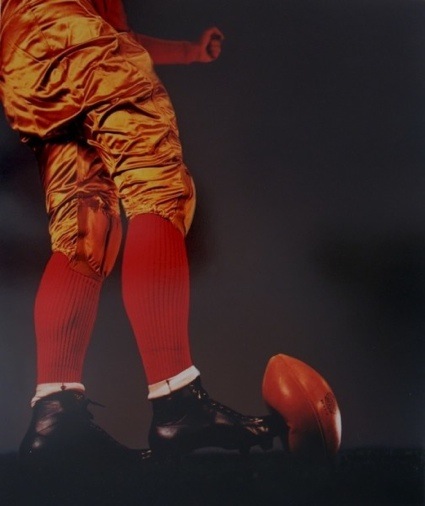

Untitled (Rugby ball), 1938

Untitled (Rugby ball), 1938

Gussie Moran, 1949

Gussie Moran, 1949

View of the gallery space

View of the gallery space

The exhibition Dr. Harold Edgerton: Abstractions is at the Michael Hoppen Gallery in London until 2 August 2014.

Image on the homepage: Antique Gun Firing, 1936.