According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, over 120 armed conflicts are raging across the world at this moment. From local struggles to full-on genocides, from the ReArm Europe plan to horrific war crimes documented live on social media, it’s getting increasingly harder to ignore the topic of war.

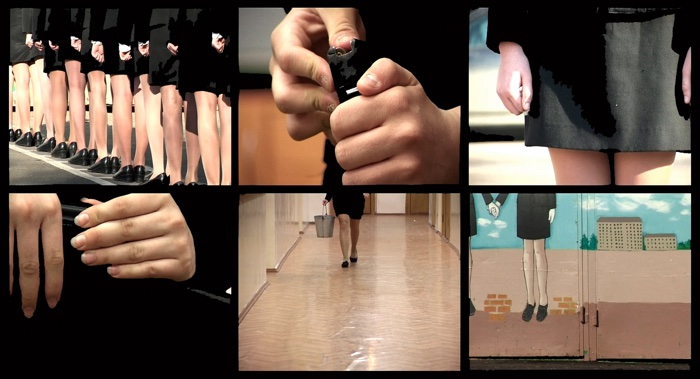

Daya Cahen, Birth of a Nation, 2010

Total Refusal, How to disappear, 2020

The exhibition de bello. notes on war and peace explores war in all its dimensions, cycles and emotional impacts. The artworks presented span six centuries of history, from a 15th-century painting to a machinima, and travel from the Middle East to South America. They are distributed over what the curators have identified as the five stages that define every conflict: appearance of peace, alarms, war, ruins, resistance.

de bello. notes on war and peace, exhibition view. Photo Diego De Pol for gresart671

The tension goes crescendo as you walk through the rooms. The first chapter of the exhibition postulates that, even in times of apparent peace, the war machine doesn’t stand still. Weapons industries thrive, territories are framed by surveillance infrastructure and techno-scientific discoveries are more or less directly subsidised by the military complex. Peace is nothing but an illusory interval.

The second chapter examines the moment that precedes the outbreak of a conflict. From sirens to the echoes of drones, that moment is filled with sounds that evoke a coming danger, intensify the feeling of vulnerability and prompt action.

Then comes the “war” section with its physical wounds and psychological traumas, its brutality weighing down on the individual and the collective. In “ruins”, cities are reduced to rubble, the landscape is scorched and dangerous. The final section speaks of resistance and the possibility of repair and reconstruction. It features gentle acts of mending and strategies to heal wounds on both human and non-human agents.

de bello. notes on war and peace is on view at gres art 671, a mid-twentieth-century industrial plant in Bergamo converted into an art space and it is good. Very very good. It demonstrates the power of art when it comes to bearing witness of violence, translating anxieties and anger into healing artefacts and resisting oppression and injustice. And, of course, advocate for peace. It is the show i needed to despair, rage and eventually find hope again.

Here are some of the most interesting works in the show:

Artist Daya Cahen: So Scary and So Beautiful | Louisiana Channel

Daya Cahen, Birth of a Nation, 2010

Daya Cahen, Birth of a Nation, 2010

Fascinated by mechanisms of indoctrination and the construction of authoritarian regimes, Daya Cahen managed to get access to Cadet School Number 9, a unique military academy in Moscow, where girls age 11-17 learn how to become the ideal Russian patriot and the ideal Russian woman. They hold Kalashnikovs while wearing large white flowers in their hair and learn how to cook, apply makeup, sew and understand military strategies.

The elite institution is part of Vladimir Putin’s patriotic education, where young girls are moulded into instruments to perpetuate the myth of Russia’s heroic destiny.

The uniforms, weapon handling, hymns to the glory of Russia and strict discipline emphasise the unity of the collective. But there are cracks in the apparent harmony. With their giggles, fiddling around and side glances, the young women betray their inner life and desire to preserve their individuality. The viewer is left with a question: does patriotism require the erasure of independent thinking?

Jonas Staal, Propaganda Theater, Video Study, 2023

Propaganda Theatre is part of Jonas Staal’s ongoing artistic research into propaganda which he sees not as a mere manipulation of messages, but as a construction of reality, a “performance of power” that stages new worlds. In the video, Staal explains how artists, directors, game designers, architects and writers are essential contributors to these spectacles, illuminating propaganda as a global theatrical enterprise in which cultural actors become unwitting – or conscious – accomplices in the scripting of alternative realities that reshape our perception of truth. And as for us, very ordinary citizens, how much more convincing and manoeuvring will it take till we believe that another war might be a good idea?

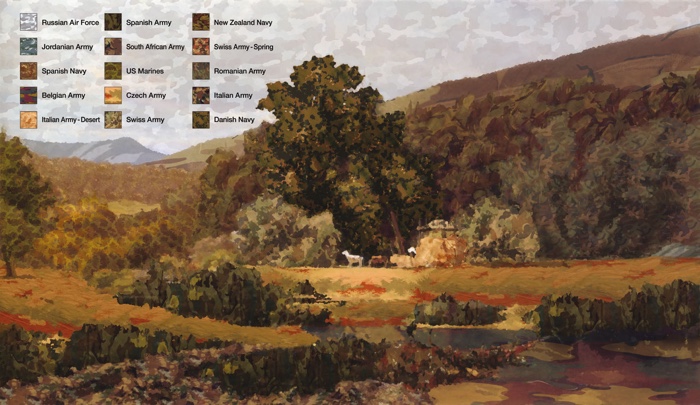

Mateo Maté, Uniformed Landscape 10 (Hugh Bolton Jones: Summer in Blue Ridge, 1874), 2007

Paisaje uniformado 10 reconstructs every texture and pictorial element of Hugh Bolton Jones’ 1974 painting Summer in the Blue Ridge using military camouflage patterns from various armed forces around the world.

Mateo Maté believes that military camouflage would not have existed without the language and iconography developed by pre-impressionists and impressionists. The artists from that movement reinterpreted landscapes as an impression of spots and colours. Around the same time, the uniforms of armies around the world changed radically; they went from being a representative and powerful element to being part of the offensive arsenal. The uniforms began to use patterns, spots and colours that imitate the natural environment.

By using the textures of army uniforms to recreate landscape paintings, Mateo Maté is trying to return this iconography to the original works of art. Each texture, type of terrain, vegetation and climatic phenomena that define a landscape finds its equivalent in some corps of some army on the planet.

The use of military uniform designs as raw material underlines the idea that no innovation or technological advancement remains untouched by the mechanisms of war.

Two Persian carpets -one from the 17th century, the other from 20th-century Afghanistan- tell a similar story but from a domestic point of view:

Persia, Tabriz (?), XVII sec and Baluch, Sarkilimdar, Afghanistan, 1979-1988

In the Safavid era (c. 1501-1722) to which the oldest garden carpet belongs, the practice of hunting was seen as akin to preparation for war, through the domination of nature and animals. The scene features hunters on horseback or on foot pursuing bears and antelopes in dense vegetation.

The second carpet is an example from the tradition of Afghan war rugs that emerged during the Soviet occupation of 1979-1989. Afghan rug makers began incorporating the apparatus of war into their designs almost immediately after the Soviet Union invasion. They continued to do so when the United States invaded the country in 2001. The weaving of weapons and war scenes is akin to a visual chronicle of the conflict. Apart from the two rows of planes and helicopters in the upper portion, the carpet depicts a natural landscape of tree-lined mountains, a river and flower pots beside a mosque. In addition to documenting war, war rugs have been a source of livelihood for displaced communities, representing both an artistic practice and a means of cultural resilience.

Alfredo Jaar, Milan, 1946: Lucio Fontana visits his studio on his return from Argentina, 2013

Alfredo Jaar’s light box shows an archive portrait of Lucio Fontana exploring the ruins of his Milanese studio destroyed by bombs during the Second World War. The work is part of Jaar’s reflection on the social responsibility of art in a global context marked by injustice, humanitarian crises and political oppression. For the artist, who trained in the Chile of Pinochet’s dictatorship, the photo corresponds to a precise historical moment in which art and culture have the capacity to influence the political and social renewal of a nation. In less than twenty years, an extraordinary group of Italian intellectuals – including Fellini, Pasolini, Pistoletto, Manzoni, Moravia, Rossellini and Visconti – developed a sort of “aesthetics of resistance” and contributed, through art, to the efforts of reconstruction in their country.

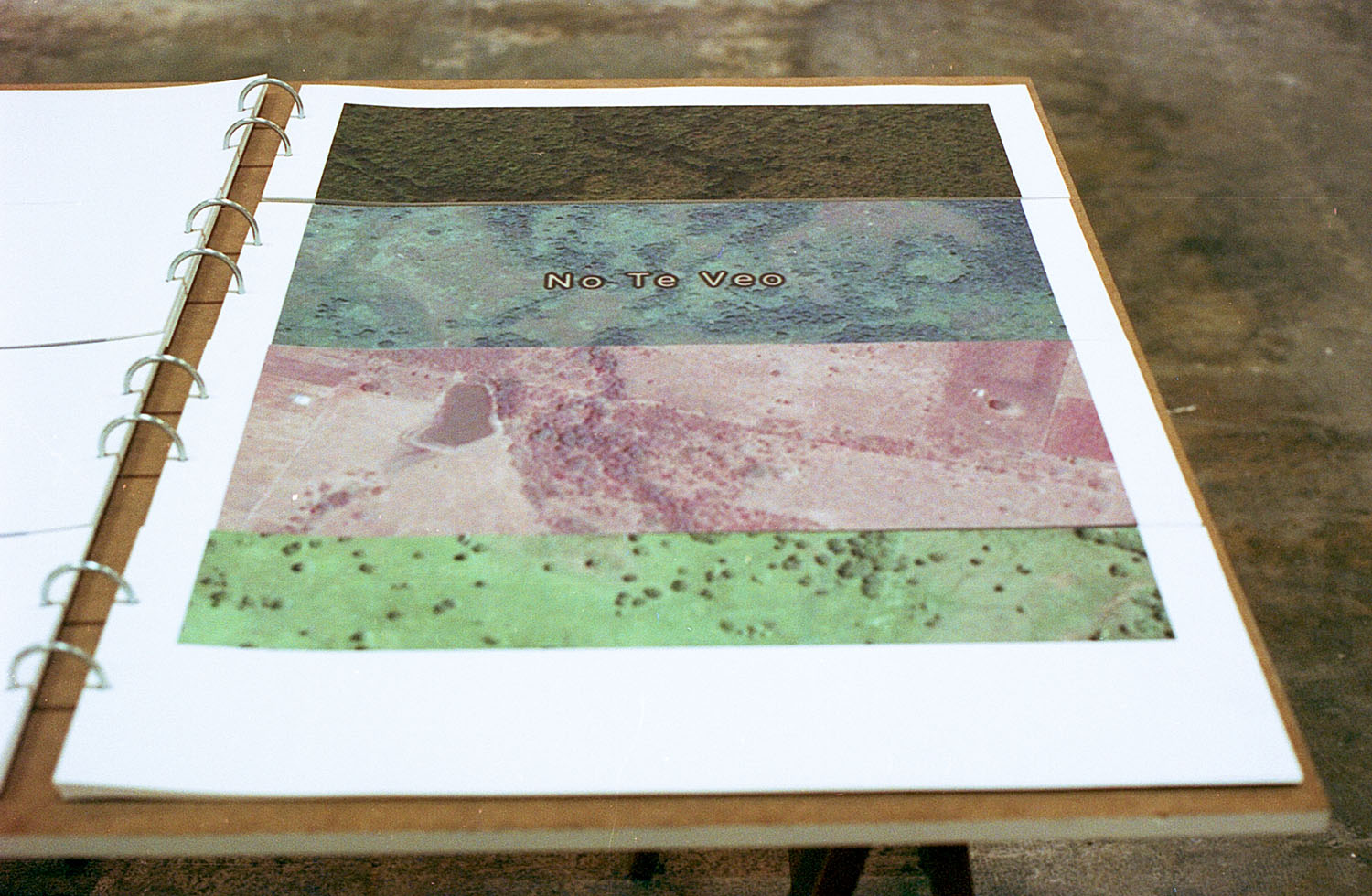

Antonio Bermúdez Obregon, Toponyms for a distracted state, 2018

Antonio Bermúdez Obregon, Toponyms for a distracted state, 2018

Toponyms are often derived either from topographical features or socio-political events. In Colombia, toponyms sometimes contain traces of conflicts, abuse and displacement. Antonio Bermúdez confronts these narratives of violence through a collection of aerial photographs of the Colombian territory. Each photo is accompanied by its associated place names, sometimes suggestive, sometimes puzzling: Lindas cosas, No hay como Dios, Ya se sabe, Dios te salve, Qién fue, Sal si puedes, etc. (Pretty things, There is no God like God, It is well known, God save you, Who was it, Get out if you can, etc.) They reveal how the traumas associated with an unstable political landscape become embedded into the territory. The simple act of naming a place thus becomes an act of violence, just like drawing lines on a map.

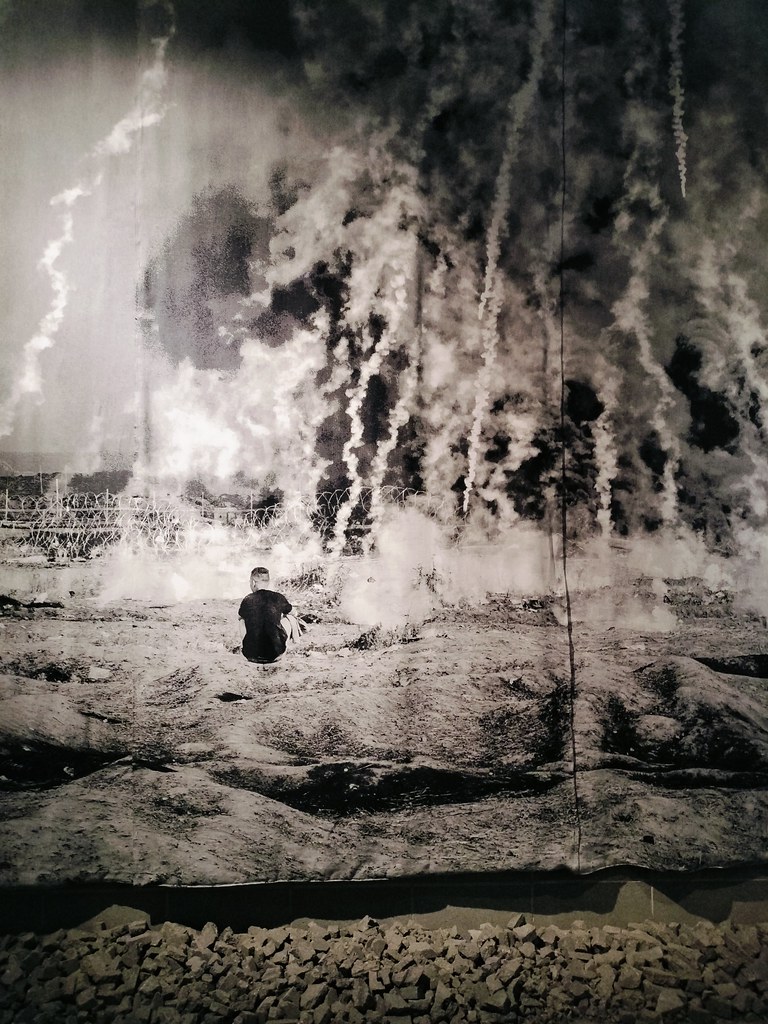

Gabriele Micalizzi. de bello. notes on war and peace, exhibition view. Photo Diego De Pol for gresart671

Gabriele Micalizzi, Gaza, State of Palestine, 2018 (detail)

Gabriele Micalizzi. de bello. notes on war and peace, Gres art 671, exhibition view. Photo: Marco Gambare

War reporter Gabriele Micalizzi transformed some of his unpublished war photographs into very large cotton tapestries which he then hung over rubble. The huge black and white images portray moments from the end of the battle of Mosul, the March of Return in Gaza in 2018, the Arab Spring in Tahrir Square in 2011 and the strike on Mariupol Theatre. “When people flee conflicts, they always take family photos. It’s people’s identity: for the same reason, back in the Middle Ages, they took tapestries with them,” the photographer explains.

Monira Al Qadiri, Onus, 2023

de bello. notes on war and peace, exhibition view. Photo Diego De Pol for gresart671

The trauma of war and the disorienting nature of our post-truth world materialise in Onus, a sculptural installation of oil-soaked glass birds. The distressing scene evokes the aftermath of the Gulf War (1990-91), in which 700 oil wells burnt for almost two years, provoking one of the worst man-made ecological disasters in history. The catastrophe killed countless birds, fish, livestock and other animals. Al Qadiri was shocked to learn that many abroad dismissed the photographs of these oil-soaked animals as fake or propaganda. Through these glass sculptures, the artist questions the fragility of memory and the psychological blindness of those who reject the reality of images. Although a witness to the destruction herself, the artist’s lived experience was challenged by people who had not experienced the ecocide. By recreating these birds as glass objects, the artist made tangible the disaster she witnessed while demonstrating the fragility of our memories when images move across time, space and cultures. This was one of my favourite works in the show. First, because of the beauty and delicacy of the bird sculptures, but also because it was one of the few works in the show that didn’t put the human front and centre.

Total Refusal, How to disappear, 2020

Total Refusal, How to disappear, 2020

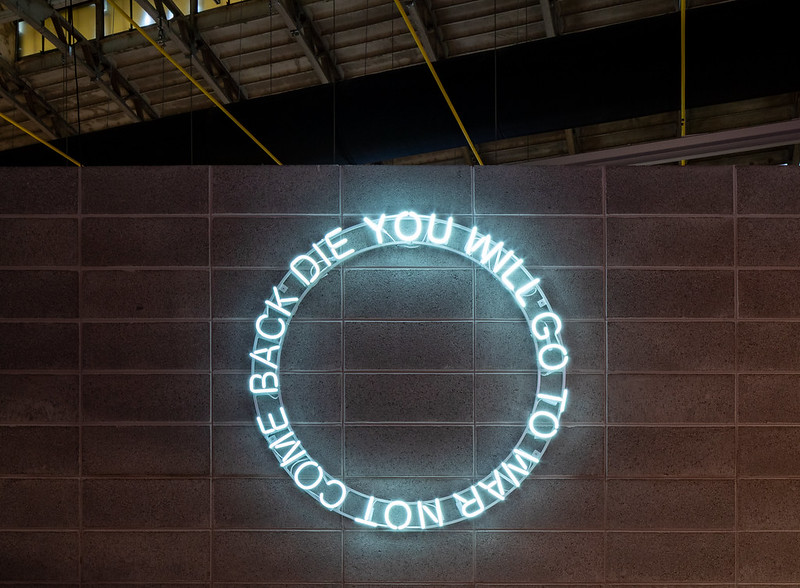

How to Disappear is a machinima from Battlefield V, a first-person shooter videogame designed solely to allow gamers to fight and kill. Total Refusal uses the war game as a place to think about disobedience in war and games.

In Battlefield V, it is absolutely impossible to refuse to participate in the confrontations, drop your weapon, prevent another avatar from firing or desert. Unlike in real wars. Because there’s no war without desertion. Throughout history, deserters have been punished for their refusal to engage in violence. Deserters carried a stigma. They were called sick, unmanly, weak, despicable. The narrator’s voice explains that the deserter is what Karl Marx would call a productive force in society. The deserter produces disobedience in war which in turn brings about a range of disciplinary, penal and surveillance tools. The deserter changed way wars are thought and fought.

How to disappear is an anti-war plea, an homage to the often anonymous soldiers who disobeyed, resisted and deserted.

Mohamed Choucair, UAI (Unmanned Aerial Instrument), 2024

Lebanese artist Mohamed Choucair’s Unmanned Aerial Instrument (UAI) transforms the omnipresent buzz of Israeli surveillance drones over Beirut into a musical composition.

The musical rack processes recordings of the drones that Israel launched over the Lebanese airspace. The system provides audio files of the drones compatible with music production software, allowing musicians to integrate these militarised sounds into creative works. Through this open sourcing of sounds associated with surveillance and terror, Choucair turns military oppression into creative material.

More works and images from the show:

Salvatore Garzillo, L’ultimo treno dal Donbas (The last train from Donbas.) Part of the series In carta e ossa, 2022

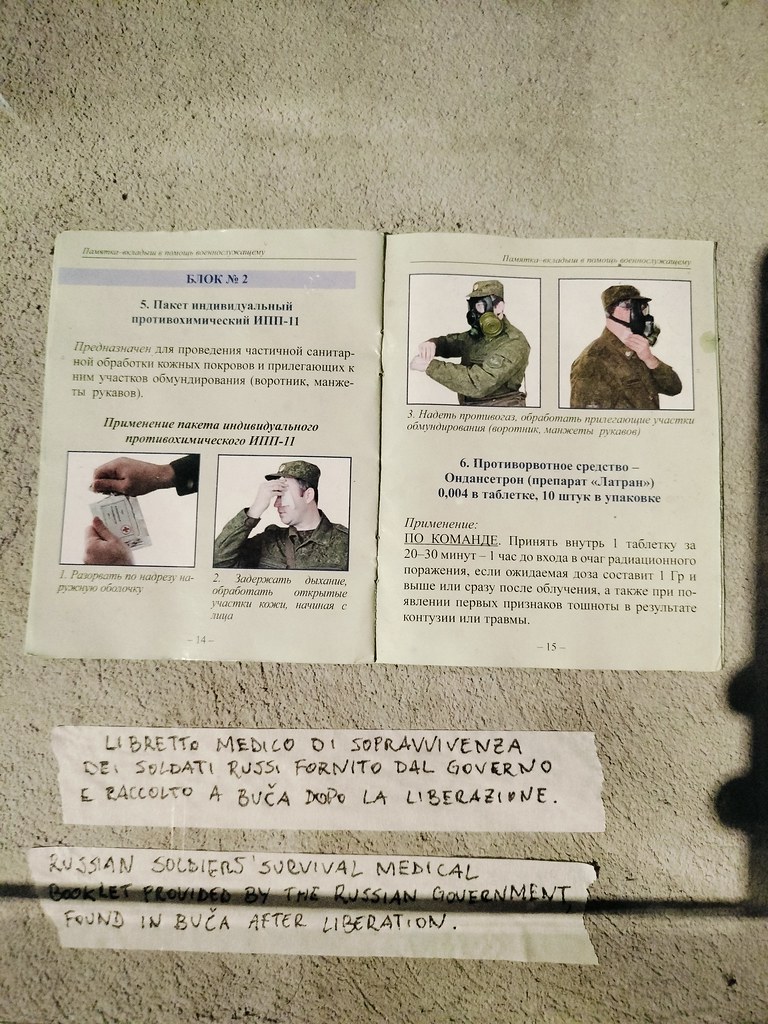

Russian soldier survival medical booklet distributed by the Russian government and found in Buča after the liberation. One of the objects collected by Salvatore Garzillo in Ukraine

de bello. notes on war and peace, exhibition view. Photo Diego De Pol for gresart671

de bello. notes on war and peace, exhibition view. Photo Diego De Pol for gresart671

de bello. notes on war and peace, exhibition view. Photo Diego De Pol for gresart671

de bello. notes on war and peace, exhibition view. Photo Diego De Pol for gresart671

de bello. notes on war and peace, curated by gres art 671 (Francesca Acquati) and 2050+ (Erica Petrillo, Ippolito Pestellini Laparelli), after an idea by Salvatore Garzillo and Gabriele Micalizzi. It remains open until 12 October 2025 at gres art 671, Bergamo.