Cultures of Violence. Visual Arts and Political Violence, by Professor of political philosophy Ruth Kinna and Senior Lecturer in visual and material culture Gillian Whiteley.

Publisher Routledge writes: Investigating art practitioners’ responses to violence, this book considers how artists have used art practices to rethink concepts of violence and non-violence. It explores the strategies that artists have deployed to expose physical and symbolic violence through representational, performative and interventional means.

Publisher Routledge writes: Investigating art practitioners’ responses to violence, this book considers how artists have used art practices to rethink concepts of violence and non-violence. It explores the strategies that artists have deployed to expose physical and symbolic violence through representational, performative and interventional means.

It examines how intellectual and material contexts have affected art interventions and how visual arts can open up critical spaces to explore violence without reinforcement or recuperation. Its premises are that art is not only able to contest prevailing norms about violence but that contemporary artists are consciously engaging with publics through their practice in order to do so. Contributors respond to three questions: how can political violence be understood or interpreted through art? How are publics understood or identified? How are art interventions designed to shift, challenge or respond to public perceptions of political violence and how are they constrained by them? They discuss violence in the everyday and at state level: the Watts’ Rebellion and Occupy, repression in Russia, domination in Hong Kong, the violence of migration and the unfolding art activist logic of the sigma portfolio.

Artur Barrio, Defl … Situação … +S+ … RUAS, 1969. In Brazil, over the course of six months, Barrio placed hundreds of bloody bundles of rotting flesh in public locations for people to discover, with a view to provoking outrage at the military regime’s brutal elimination of political activists

Cover of the United Kingdom edition of Sroja Popovic’s ‘handbook’ Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men, and Other Nonviolent Techniques to Galvanize Communities, Overthrow Dictators, or Simply Change the World

How could I resist a book that scrutinizes cultural interactions with social and political violence?

The artistic and intellectual practices investigated in the various essays not only decry forms of violence that might not always be visible but also respond to them with strategies that range from poetical hijacking of public space to backing of wider grassroots movements, from playful collaborations with migrant workers to utterly bonkers performance that stunned passersby. By engaging head-on with the work of activists, with the struggles of fragilized communities and more generally with a broader culture of violence, the initiatives explored in Cultures of Violence have the potential to re-shape social dynamics.

The book contains only 5 essays, plus the introduction by the editors but it covers enough ground to trigger the curiosity of readers who might not be familiar with the topic and the surprise of those who might already have a strong interest in it. The quality and style of the essays is a bit unequal but I liked the balance between contemporary practices and dips into past moments that echo some of today’s most pressing issues (African American movements with a potential to transform a wider social infrastructure, inability to envision a future that isn’t dystopian, commercialisation of shock, etc.)

The essay that, by itself, makes it worth getting the book is the one in which researcher Amy Corcoran examines artistic interventions designed to reveal and challenge the state violence implicit in bordering and migration. I found that the style and the content of her text mirrored the commitment of the visual practices she describes as attempting to foster intuitive connection and encounters with broad audiences.

Kennard and Phillipps, In Humanity, 2016

Corcoran identifies 3 main artistic strategies to contest state-led political violence, connect with activism and bring about social transformation: (de)legitimation, education and empathy or emotional connection.

I found the paragraphs on (de)legitimation particularly interesting. She convincingly argues that legally sanctioned state actions -from police violence to government inaction, from enforcement of national borders to forced deportation of asylum seekers- can be regarded as acts of violence and as such, are morally reprehensible. Accordingly, it is legitimate to denounce and resist such state violence, even using defensive violence.

Her essay highlights a number of artistic interventions that push back against state-endorsed violence and connect with grassroots resistance. I’m listing a couple of them below:

Public Studio and Adrian Blackwell, Migrant Choir, 2015

Migrant Choir: migrants stuck in Italy sang the French, British and Italian national anthems outside the national pavilions at the Venice Biennale. Information booklets distributed to visitors explained the wider situation but did not promote any particular campaign or course of action. The intervention was designed to generate an affective tension between the feeling of ‘home’ generated by the anthems and the situations of the singers.

Tammam Azzam, Kiss, 2013. Photo via ISIS

Tammam Azzam digitally laid Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss over a bombed-out building in Damascus, poetically depicting physical state violence and the structural forces that fuel it. The work breaks the barrier of attention fatigue and turns what has become a favourite museum postcard into a powerful plea for empathy that unsettled Western audiences when they first saw it.

Center for Political Beauty, Eating Refugees, 2016

Center for Political Beauty’s Eating Refugees contested a law that prohibits refugees from flying into the EU without a visa. Through its use of various provocative stunts (including a Roman-style arena for refugees to be devoured by tigers), the work generated debates among members of the public who might otherwise not be willing to engage with performance art or politics.

Manaf Halbouni, Monument, 2017. Photo: David Brandt

Different audiences will respond differently to a socially-engaged work. In 2017, Manaf Halbouni installed three upturned buses in Dresden’s central square, referencing a well-known photo from Aleppo where a community had used bombed-out buses as a barricade. The statue, erected to mark the anniversary of the Allied aerial bombing of Dresden during World War II, attempted to establish “a connection between the people of the Middle East and Europe and our shared destinies” and alluded to “the suffering and unspeakable losses as well as the hope for reconstruction and peace.” Unfortunately, the artwork was met with protests by right-wingers who claimed the installation represented an abuse of artistic freedom and a ‘snub’ to the views of Dresden residents.

Dr Martin Lang‘s essay also looked at how cultural resistance responds to political violence. His approach, however, is more historical. First, because his text spans fifty years of transatlantic activism, from the 1965 Watts Rebellion in Los Angeles to the global Occupy movement of 2011, his examination of activist struggles. Second, because he examines this political violence through the lens of Situationist International, an organisation of social revolutionaries that started with a predominantly artistic focus in 1957 but moved gradually towards revolutionary and political theory. Born as a mostly European movement, the SI took a keen interest in US race relations and civil unrest, imagining the Watts riots as the first step in a broader struggle in which, they predicted, African Americans might be able to “unmask the contradictions of the most advanced capitalist system.”

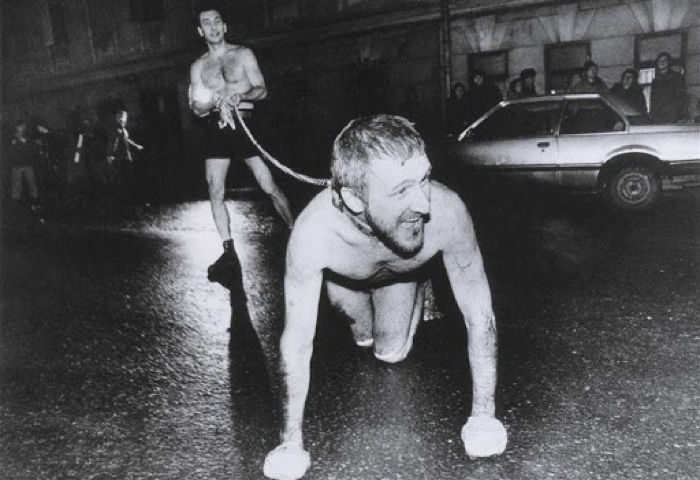

Oleg Kulik , The Mad Dog or Last Taboo Guarded by Alone Cerberus (with Alexander Brener) Yakimanka Street. Moscow, November 23, 1994

In her contribution to the book, art and cultural historian Marina Maximova explores the most provocative works of Oleg Kulik as well as the strategies of Moscow Actionism, the radical strain of Russian performance art that emerged in the early 1990s in response to the violence prompted by the collapse of the Soviet regime and the transformation of social life under the new capitalist order.

The often outrageous way these artists used public space took advantage of the small window of time between the Soviet period, when public spaces were submitted to strict political control and surveillance, and the emergence of new exclusive hierarchies which from the 2000s onwards resulted in the loss of the ‘publicness’ of space in urban areas. In that short timeframe, artists saw in violence and provocation the only appropriate response to the sociopolitical conditions they were witnessing and experiencing.

E.T.I. Movement, E.T.I.-text, 1991. Photo via Calvert Journal

An example of such urban space intervention was E.T.I. collective’s reaction to the Act on Morality of 1991, which prohibited the use of obscene language in public spaces, the group spell out a Russian swear word with their bodies on the pavement in front of the Red Square. ETI’s action typifies the Moscow Actionists attempts to win back the right to express themselves in the public sphere, often by adopting the strategy of ‘public mischief’.

Oleg Kulik is perhaps the artist whose practice pushed this shock strategy to its most brazen limits. His street interventions became also for him a mode to explore the effect of his actions on audiences that would otherwise never visit his gallery exhibitions. His most famous performance is probably the one in which he roamed the streets naked and played the part of a dog. I had no idea, however, that he founded his own party: Partiia Zhivotnykh (the Party of animals.) During his political campaign, the artist ran on a central Moscow street wearing a muzzle and a chain, howled in front of journalists at a dog show and used the slogan ‘being a homo sapiens is like being a fascist!’ in his election campaign.

Interestingly, Kulik found that even though his work responded to the specific Russian context, its violence was very well-received in the West and he was invited to do similar performances in various European and U.S. cities.

In their joint text, researcher, lecturer and curator Vlad Morariu and artist and curator Jaakko Karhunen discuss sigma, a network of writers, artists, scientists and psychiatrists active between 1963–1965. Their most tangible achievement was the sigma portfolio, a collection of texts, ‘part manifesto, part manual’ for art activism. Their writings explored, for example, how architects could use their skills to redesign spaces for creative sharing, education and knowledge production or how cultural practitioners could develop new means of distribution for art and literature that would break through traditional media and even mainstream consumer goods.

The most fascinating part of the essay dives into Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi and Mark Fisher‘s perspective on the shifting vision, visuality and ideology of possible futures. The first part of the 20th century was characterised by unwavering trust in the future. In the aftermath of 1968, however, utopian imagination and ideology of progressive future turned into dystopia, and cyberculture, the last utopia of the twentieth century slowly died of mental exhaustion. Berardi calls it a ‘paralysis of the will’, Mark Fisher ‘the slow cancellation of the future’.

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Hong Kong Intervention, 2009. Photo: Hong Wrong

Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Hong Kong Intervention, 2009. Photo: Hong Wrong

Lecturer in Visual Communication Jessica Holtaway considers Sun Yuan and Peng Yu‘s Hong Kong Intervention, an artwork that invited 100 migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong to place and photograph a plastic toy grenade in their employers’ homes. The image was accompanied by a photo of the participants with their back to the camera to preserve their anonymity. The work drew attention to political issues surrounding the working conditions and rights of migrant domestic workers who make up nearly 5% of the local population.

Holtaway analyses how, by staging the scene the work through the eyes of the migrant worker, the artists challenge the viewer to become an accomplice in the intervention. By involving so many participants -the audience, the workers, the artists- Hong Kong Intervention flattens out power structures, makes visible the often invisibilised domestic workers and act as a springboard for a broader discussion about the often poorly respected human rights of domestic workers.