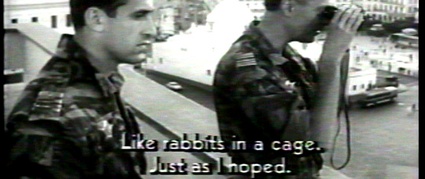

Image from Slingshot Hip Hop

Image from Slingshot Hip Hop

I normally don’t blog about events i can’t attend but some cultural initiatives call for exceptions. Cruel Weather. Arab Middle East Film Festival is a festival of recent film/video from the Arab Middle East that opens in Aberdeen on October 2 and will move to other Scottish cities afterward. In parallel with the movie, Peacock Visual Arts is setting up Identities in Motion, an exhibition of Ayah Bdeir‘s work, a media artist whose ingenious and sometimes tongue-in-cheek projects invite us to have another look at media’s tendency to flatten the Arab identity and reduce it to a set of cliche images and iconographies.

Ayah Bdeir, Teta Haniya’s Secrets, a line of electronic lingerie inspired by a Syrian tradition of hacking electronic toys

Ayah Bdeir, Teta Haniya’s Secrets, a line of electronic lingerie inspired by a Syrian tradition of hacking electronic toys

Cruel Weather explores artistic responses to crisis and the role of the moving image in today’s Middle East. The festival showcases a series of award-winning documentaries, experimental and mixed genre works, many of which have never before been screened in Scotland.

I asked the curator of the festival, Jay Murphy, of the University of Aberdeen’s Centre for Modern Thought a few questions about Cruel Weather:

Why did you call the festival “Cruel Weather”?

I hope it’s an imaginative title. There is a sort of maelstrom going on in the Middle East, and it’s cruel in that much of this suffering is avoidable. Although many of us may feel disconnected from it, it is directly related to U.S. and U.K. actions, and the acquiescence of the E.U. I have a writer friend in New York who feels when she’s going down the street as if she is walking on corpses, but a profound dissociation is far more typical.

Jayce Salloum & Elia Suleiman, Introduction to the end of an argument (1990)

Jayce Salloum & Elia Suleiman, Introduction to the end of an argument (1990)

How did you get to be involved in films from Arab Middle East?

I’ve been involved in Palestinian solidarity work of one kind or another from the late ’80s on. It was the theme of an issue of the magazine I did at one time, Red Bass, in 1988, and then a book anthology I edited that was published in 1993. At first it was a matter of competing representations, since the Palestinian struggle on film was rare at one point, and Palestinian filmmaking a small handful of people, whereas now there are widening developments, and remarkable talents like Elia Suleiman who take things to another level altogether.

“Cruel Weather” is in another period and concerns itself with another matter: it is not an issue so much of righting or balancing the censorship of points of view (not that this is resolved, far from it, especially in countries like the United States), but of providing a glimpse of a very inventive and wide-ranging creativity that has gained momentum especially just in the past decade.

It’s hard not to detect some political undertones in the festival’s programme. Do you expect Cruel Weather to stir controversy?

It would be very controversial in much of the U.S. and England, but there is a different political complexion in Scotland (due to its own colonized history perhaps?). There could still be a backlash, but I’ve only seen very solid support for this idea. It is also meeting a real need, since to our knowledge (and those of our partners in Glasgow, Edinburgh, and Dundee), none of these works have been screened here before.

Image from Chaos (2007) (c) Youssef Chahine. Courtesy: Pyramide International

Image from Chaos (2007) (c) Youssef Chahine. Courtesy: Pyramide International

The films you selected speak of dynamism, hip hop music, culture jamming, future, etc. They explore several regions of Arab Middle East. How did you choose the movies to be presented in the festival?

I remained with the work from the Levant and Egypt, because I’m most familiar with that, also being mindful of the limitations of our resources and time, since there are many films emerging from the Middle East, and video is a tool used across the region. I also think much of the best work has come from those spots, although what the festival often reflects is more of a thoroughly globalized poetics of location from artists on the move rather than specific geography. I feel the selection is somewhat unpredictable and quirky (Roy Samaha’s video is inspired as much by William Burroughs’ “cut ups” and Carlos Castaneda as contemporary Beirut, Chahine‘s “Chaos” is not one of his best received films, other films have a raw and improvisatory quality, while “Slingshot Hiphop” is a very assured first feature from Jackie Salloum), even while including some of the usual suspects.

Slingshot Hip Hop trailer:

Could you tell us a few words about the state of cinema making in Palestine? Are there organizations, structures and schools for documentary, animation and feature-film directors in the country?

There have been initiatives like the Cinema Production and Distribution Centre, started by filmmaker Rashid Masharawi in 1996, there is a virtual gallery at Birzeit University, and a number of filmmaking collectives, of which Annemarie Jacir‘s Palestinian Filmmakers Collective is only the best known; foundations like the A.M. Qattan Foundation, support residencies and awards and training for young artists, including filmmakers. But I think largely the infrastructure is still very embryonic, and most filmmakers study in the metropolises to learn their trade, and bring that knowledge back home to bear on its current realities.

Image from This Day (2003). (c) Akram Zaatari. Courtesy Video Data Bank

Image from This Day (2003). (c) Akram Zaatari. Courtesy Video Data Bank

An exhibition of artist Ayah Bdeir accompanies the festival. Can you tell us something about the works selected for the show? How does her exhibition complement the film festival?

Ayah Bdeir was the choice of the outgoing curator at Peacock Visual Arts, Monika Vykoukal, and I think she is a perfect choice in her play with cultural expectations, her diversity, inventiveness and range, which goes from animation and visuals for music concerts (such as Guy Manoukian‘s August 9 at Beiteddine, Lebanon outside Beirut) to electronic lingerie (Teta Haniya’s Secrets).

Arabiia, September 2007. Photo: Kate Kunath

Arabiia, September 2007. Photo: Kate Kunath

Bdeir was born in Montreal but grew up in Beirut, and is currently a senior fellow at Eyebeam in New York; the issue of ‘tradition’ and identities and their relations with the metropolis are all foregrounded and problematized in her work, as they have to be. Bdeir participates in this very radical questioning of identity (for example in Jayce Salloum’s “there is no Arab art”) or probing the “withdrawal” of tradition (as in Jalal Toufic‘s writings) that is also central to the film and video artists presented here. As Toufic has written, “We do not go to the West to be indoctrinated by their culture, for the imperialism, hegemony of their culture is nowhere clearer than here in developing countries.” I think Bdeir’s work often traffics in this counter-intuitive and shifting relation of centre/periphery, in the electronically-hacked items in her The Arab Store, for instance.

Thanks Jay!

See also Jay Murphy’s essay about Cruel Weather (PDF).

Previous entries about Ayah Bdeir’s work: littleBits, pre-engineered circuit boards connected by tiny magnets, SP4M. D0 Y OU SWA1LOW? and Underwear for airport searches. Also this interview with the artist at How to Win.