Creditworthy. A History of Consumer Surveillance and Financial Identity in America, by Josh Lauer.

Publisher Columbia University Press writes: The first consumer credit bureaus appeared in the 1870s and quickly amassed huge archives of deeply personal information about millions of Americans. Today, the three leading credit bureaus are among the most powerful institutions in modern life–yet we know almost nothing about them. Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion are multi-billion-dollar corporations that track our movements, spending behavior, and financial status. This data is used to predict our riskiness as borrowers and to judge our trustworthiness and value in a broad array of contexts, from insurance and marketing to employment and housing.

In Creditworthy, the first comprehensive history of this crucial American institution, Josh Lauer explores the evolution of credit reporting from its nineteenth-century origins to the rise of the modern consumer data industry. By revealing the sophistication of early credit reporting networks, Creditworthy highlights the leading role that commercial surveillance has played—ahead of state surveillance systems—in monitoring the economic lives of Americans. Lauer charts how credit reporting grew from an industry that relied on personal knowledge of consumers to one that employs sophisticated algorithms to determine a person’s trustworthiness. Ultimately, Lauer argues that by converting individual reputations into brief written reports—and, later, credit ratings and credit scores—credit bureaus did something more profound: they invented the modern concept of financial identity. Creditworthy reminds us that creditworthiness is never just about economic “facts.” It is fundamentally concerned with—and determines—our social standing as an honest, reliable, profit-generating person.

Creditworthy opens up in 1913 when oil magnate John D. Rockefeller is denied access to credit in a Cleveland department store. The clerk, who didn’t trust the appearance of his customer, insisted on calling the credit department before authorizing Rockefeller’s purchases. The story shows that at the time already, even one of the richest men in the world, could not escape the gaze of a surveillance apparatus that will remain under-studied for decades to come.

The book ends 100 years later when his great-grandson Senator John (Jay) D. Rockefeller IV initiates a senate investigation into the business practices of the U.S.’ leading data brokers. The results were divulged a few months after Snowden’s NSA revelations. Talking about privacy, the senator said:

What has been missing from this conversation so far is the role that private companies play in collecting and analyzing our personal information. A group of companies known collectively as ‘data brokers’ are gathering massive amounts of data about our personal lives and selling this information to marketers. We don’t hear a lot about the private-sector data broker industry, but it is playing a large and growing role in our lives.

Let me provide a little perspective. In the year 2012, which you will recall was last year, the data broker industry generated $156 billion in revenues–that is more than twice the size of the entire intelligence budget of the United States Government–all generated by the effort to learn about and sell the details about our private lives. Whether we know it or like it or not, makes no difference.

In this book, professor of media studies Josh Lauer describes how U.S. citizens became objects of intensive surveillance. He investigates how financial identity became a key marker of our personal trustworthiness and how increasingly centralised and invasive systems for monitoring an individual’s behaviour and credits enabled the ascent of consumer capitalism in the U.S.

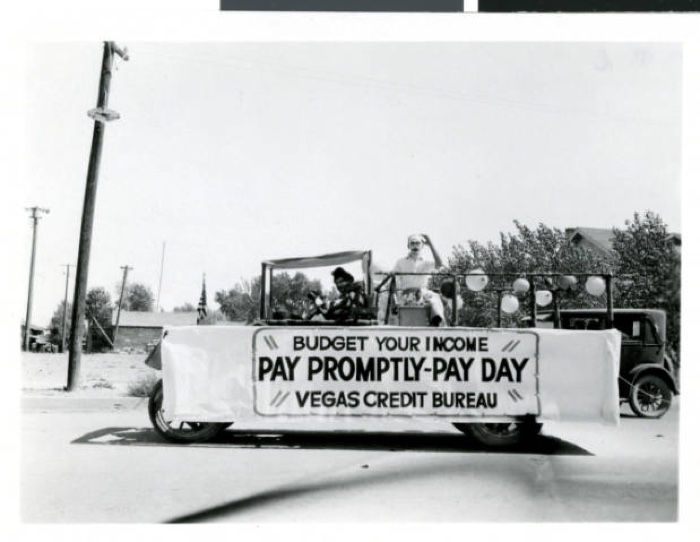

Photograph of the Vegas Credit Bureau parade entry, Las Vegas, circa late 1920s to early 1930s

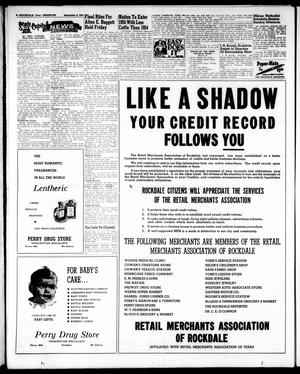

Many of us think that modern surveillance appeared after 9/11 but its history actually started in the late 19th century when a disembodied doppelganger of the American consumer started materializing inside the files of retail credit departments and local credit bureaus.

The credit reporting industry was an omnivorous collector of personal data. It cultivated trusted informants, connected with hospital and utility companies, placed phone calls to employers, landlords and neighbours in order to amass as much information as possible about American individuals. Many credit departments and bureaus even maintained separate ‘watchdog’ cabinets where they stored all sorts of information that may affect an individual’s ability to pay: divorces, lawsuits, bankruptcies or accounts of immoral behaviour gleaned from papers court and newspapers clippings, etc. The data gathered was so extensive that in the early 1960s, FBI agents, treasury men and the NYPD visited their offices when they needed to fill in gaps in their dossier.

The credit surveillance industry not only quantified the value of citizens, it also functioned as a disciplinary machine, attempting to control their behaviour, shaming them into paying back what they owed and enforcing the doctrine that a person who abused his or her credit must should be shunned from business and society. To the point that, over time, an individual’s financial identity became an integral dimension of their personal identity.

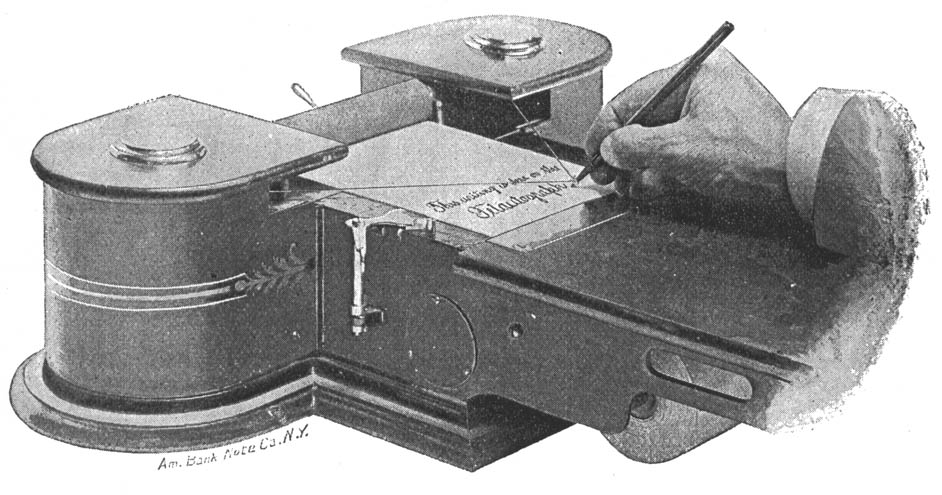

The telautograph. Image: redorbit

Trustworthy explores a very American phenomenon. We do have credit surveillance systems in Europe too but they are probably not as sophisticated as the ones described in the book (note to self: please investigate the European situation.) I’d definitely recommend this book to U.S. readers. It is impeccably researched and makes for a compelling read. I particularly enjoyed the parts describing the array of human and mechanical techniques employed to extract and manage credit information. From the personal interviews that subjected consumers to intrusive scrutiny to the new technologies that enabled the collection and archiving of data. That’s where i learned about the existence of the telautograph, a precursor to the modern fax machine that was developed to transmit drawings to a stationary sheet of paper. It was used in credit bureau, banks and doctors for sending signatures over long distances.

The Rockdale Reporter and Messenger (Rockdale, Tex.), Vol. 82, No. 34, Ed. 1 Thursday, September 9, 1954 Page: 6 of 20

Credit surveillance systems placed individuals at the center of an invasive information and communication network. Its complexity, its reach and the impact it had on society was (and is still) alarming. Yet, most American consumers have long remained unaware of the private surveillance system that facilitated their credit purchases. This lack of knowledge and control is something that most of us -U.S. citizen or not- have often deplored since Edward Snowden revealed the extent of the NSA mass surveillance infrastructure.