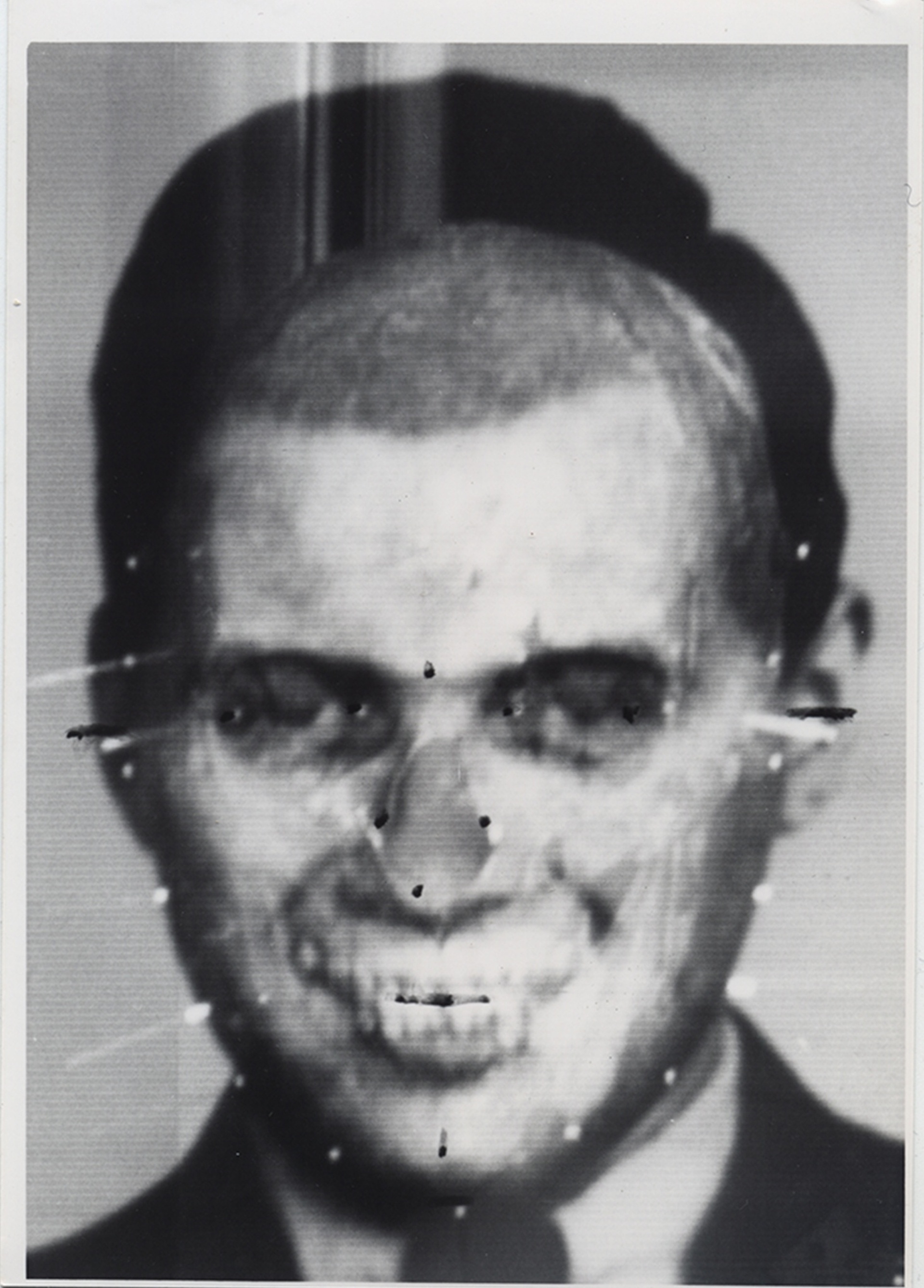

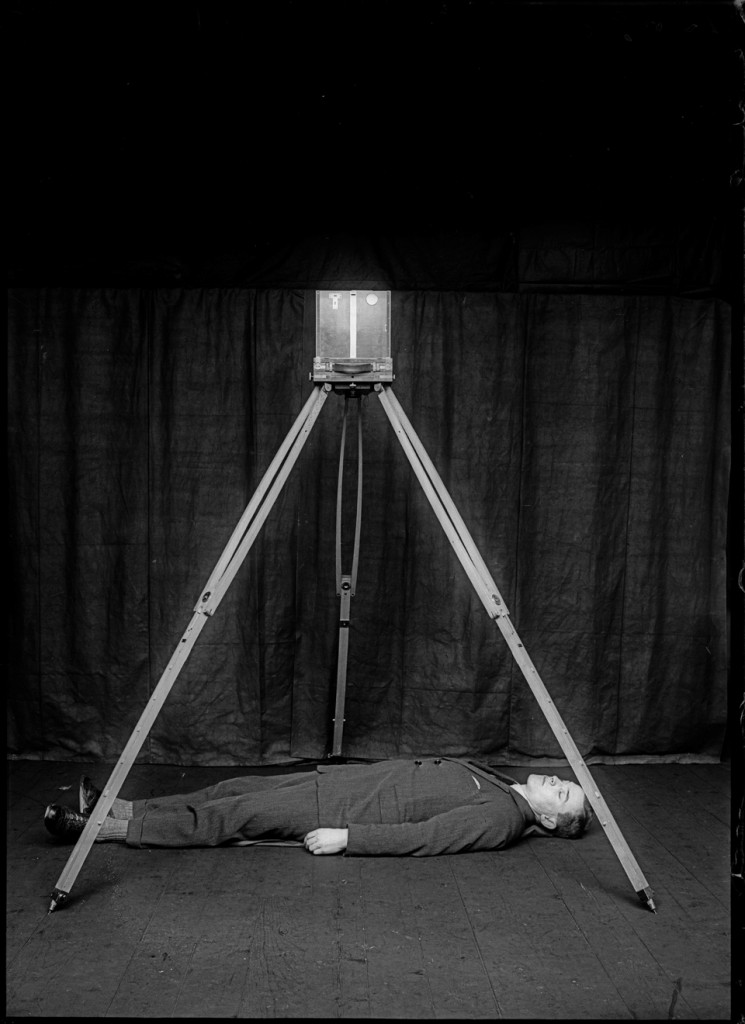

Rodolphe A. Reiss, Demonstration of the Bertillon metric photography system with a man posing as a corpse. Copyright and courtesy of R.A. Reiss, coll. IPSC

Photography extract from Decoding video testimony, Miranshah, Pakistan, March 30, 2012. Forensic Architecture in collaboration with SITA Research

Now that i’m home and properly idle for a full month, i can finally write about all the exhibitions and events i’ve attended in October and November. Starting today with the show Burden of Proof: The Construction of Visual Evidence at The Photographers’ Gallery in London.

I have a predilection for the morbid, the criminal and the distressing. When i’m not reading art/activism/architecture books for the blog, i’m reading crime books. And when i’m not watching video artworks, i spend my evenings with crime TV series (not American ones, eh!) Burden of Proof brought me the best of both world. The thrill of being surrounded by images of corpses, the pretense of visiting a cultural show.

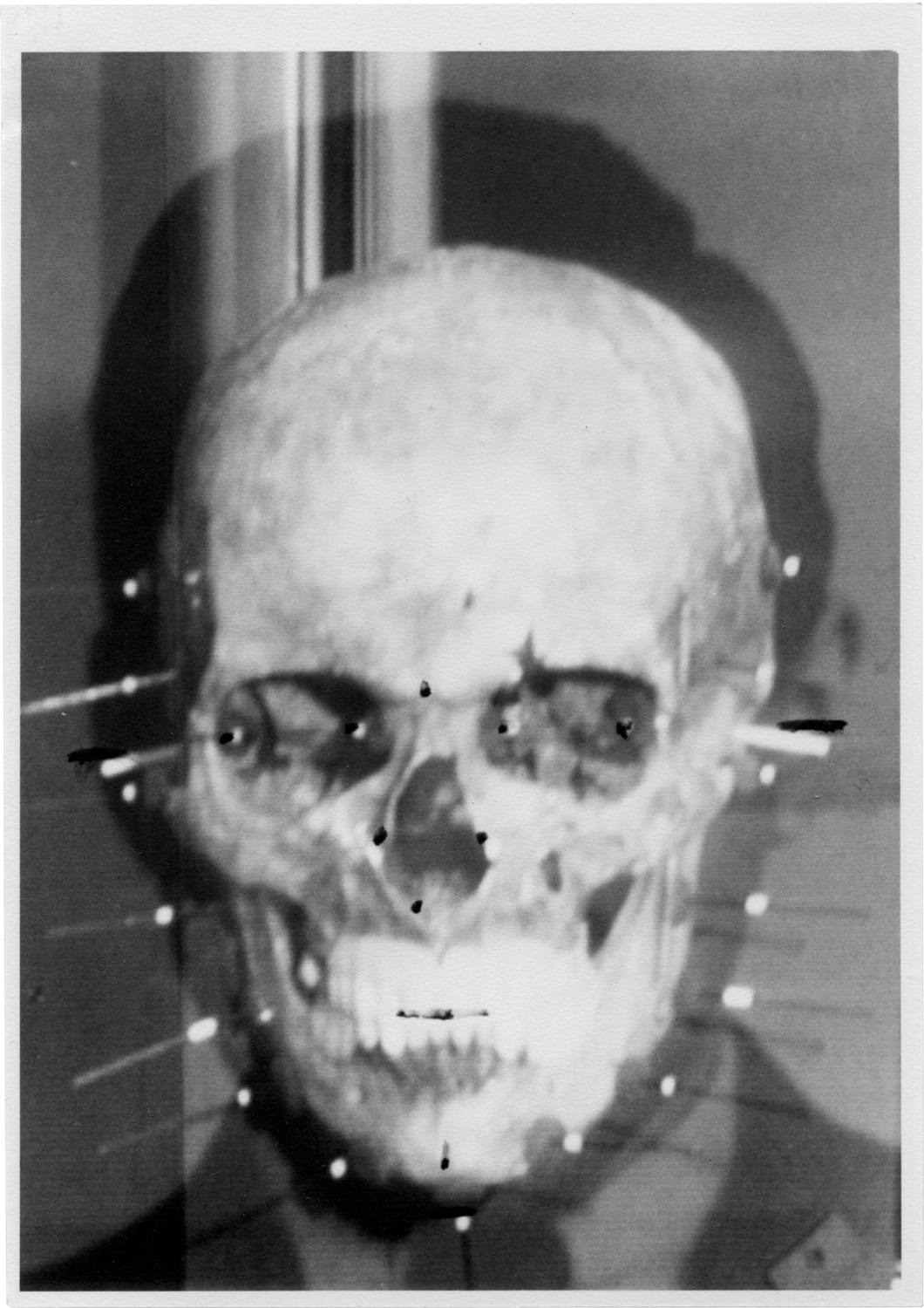

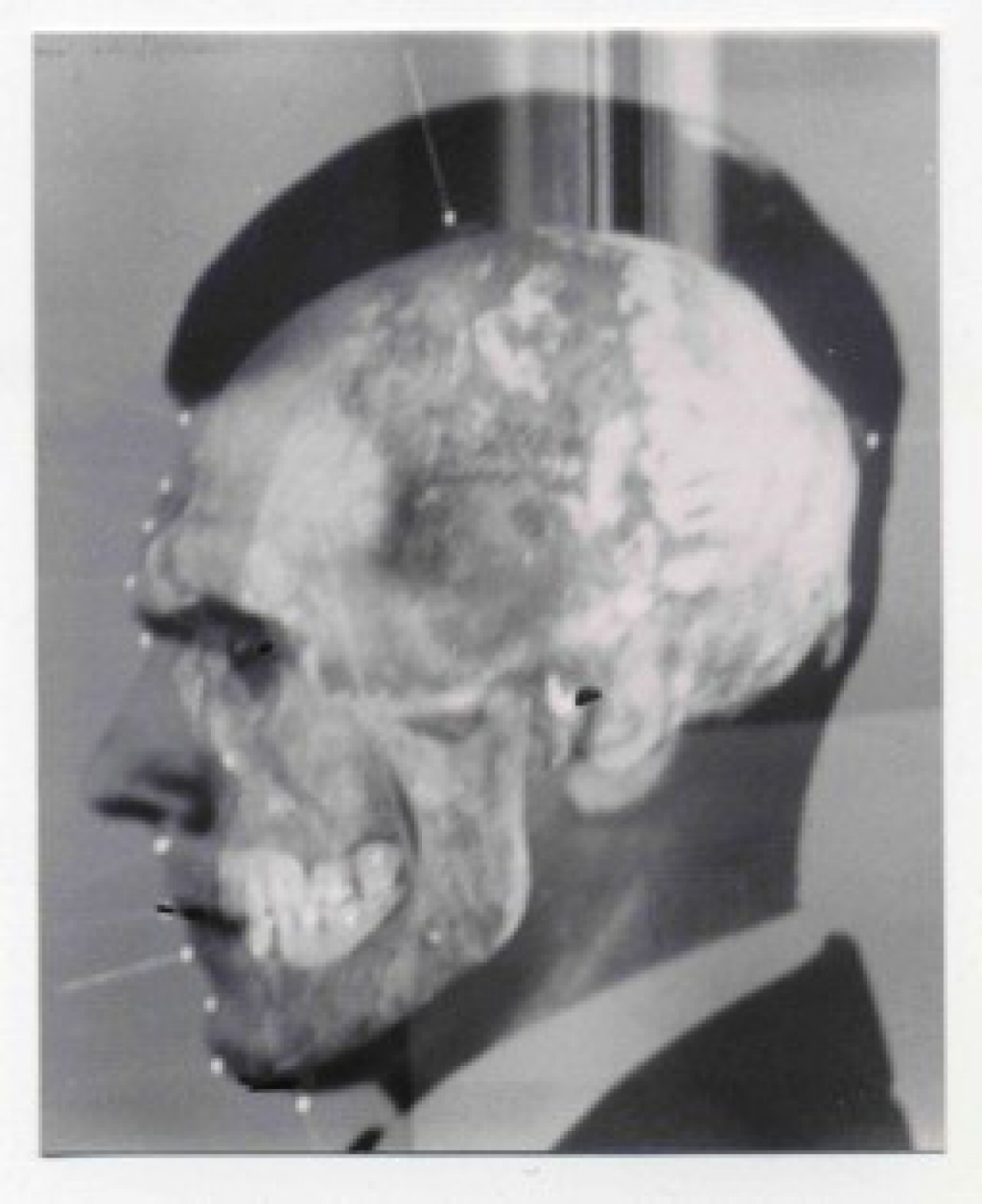

Richard Helmer, superimposition of Joseph Mengele’s photo portrait and of the skull, 1985. Photograph: Richard Helmer. Photo courtesy of Maja Helmer

The exhibition presents eleven case studies spanning the period from the invention of ‘metric’ photography of crime scenes in the 19th century to the reconstruction of a drone attack in Pakistan in 2012 using digital and satellite technologies. These offer an analysis of the historical and geopolitical contexts in which the images appeared, as well as their purpose, production process and dissemination.

While charting some of the most salient historical instances in which photography has been used as evidence of criminal activity or violent acts, Burden of Proof investigates the reliability of the images and interrogates its role in truth-seeking scientific and historical discourse.

The ambiguity of photography has been much debated. Photography, as we know well, is an instrument for revealing, documenting and exposing. But it can also be used to hide, stage or doctor evidence. It is a medium of transparency and opacity, at the service of both truth and propaganda. The exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery reminds us that, despite its evidential limitations, photography plays a role too important in society and in the service of justice to be unequivocally dismissed.

But let’s look at the cases studies, i’ve selected only a few of them and will, for once, follow the curators’ decision to present them chronologically. Almost none of the photos were made by artists but their (unintentionally) aesthetic qualities are nevertheless indisputable. I, for one, was amazed by the way the bodies in Bertillon’s photos laid on the ground like cut flowers:

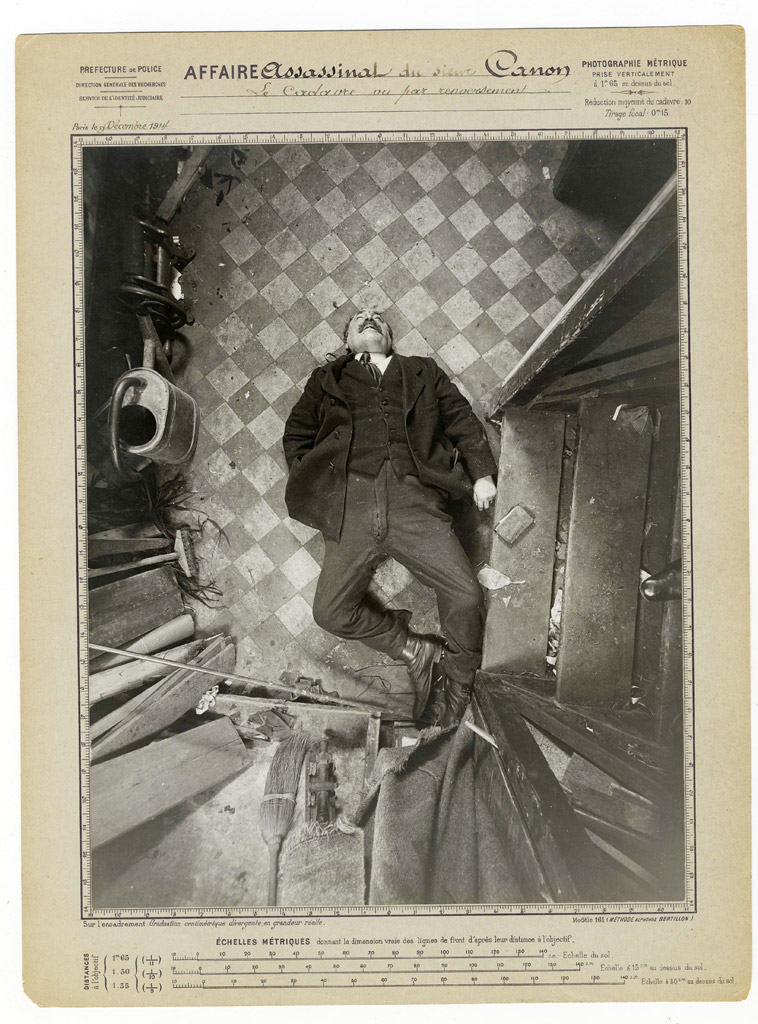

Alphonse Bertillon, Murder of Monsieur Canon, boulevard de Clichy, 9 December 1914. Archives de la Préfecture de police de Paris

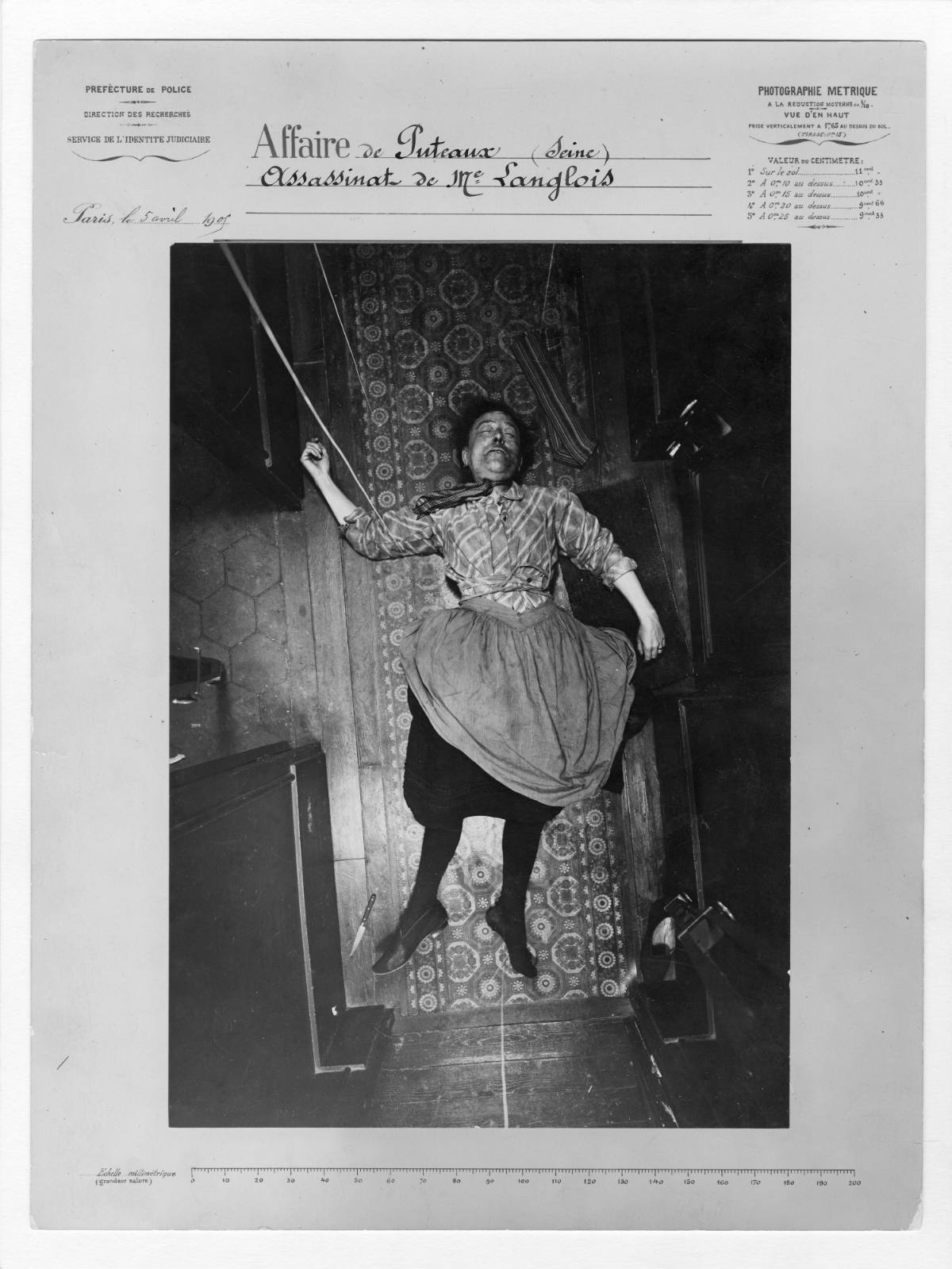

Alphonse Bertillon’s Murder of Madame Langlois, 5 April 1905. Photograph: Archives de la Prefecture de po/Archives de la préfecture de police

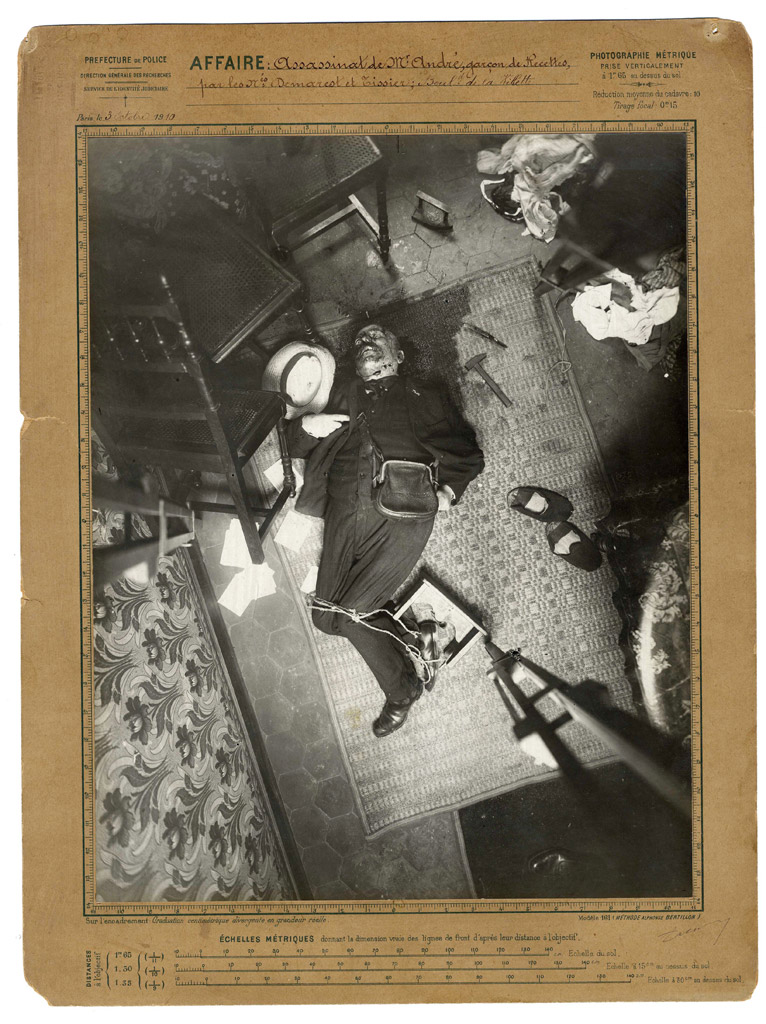

Alphonse Bertillon, Assassinat de monsieur André, boulevard de la Villette, Paris, 3 octobre 1910, Préfecture de police de Paris, Service de l’Identité judiciaire. © Archives de la Préfecture de police de Paris.

Alphonse Bertillon was a French police officer and and biometrics researcher who invented or perfected several methods of identifying criminals and solving crimes. The most famous and widely-used today is the mug shot. Sherlock Holmes, apparently, was a fan of the French criminologist.

In the early 20th century, Bertillon developed metric photography, a scientific protocol to document crime scenes. He used an overhead camera with a high tripod and wide angel-lenses that captured an ‘objective’ diving, bird’s-eye view of victims at the places of their deaths. The images were then mounted on cardboard featuring precise measurements. The final document records succinctly and visually all the material elements present at the scene of the crime: the position of the corpse and of any weapon, objects and clues nearby, foot prints, etc.

Metric photography was important not only for police work but it also played a part during trials where the images were used to make an impact on the judges but could also incite the accused to confess.

Rodolphe A. Reiss, Demonstration of the Bertillon metric photography system. Copyright and courtesy of R.A. Reiss.

Rodolphe A. Reiss, handkerchief used to strangle Madame Ducret. Beaumaroche, France, September 1907. Collection de l’Institut de police scientifique de l’Université de Lausanne © R. A. REISS, coll. IPSC

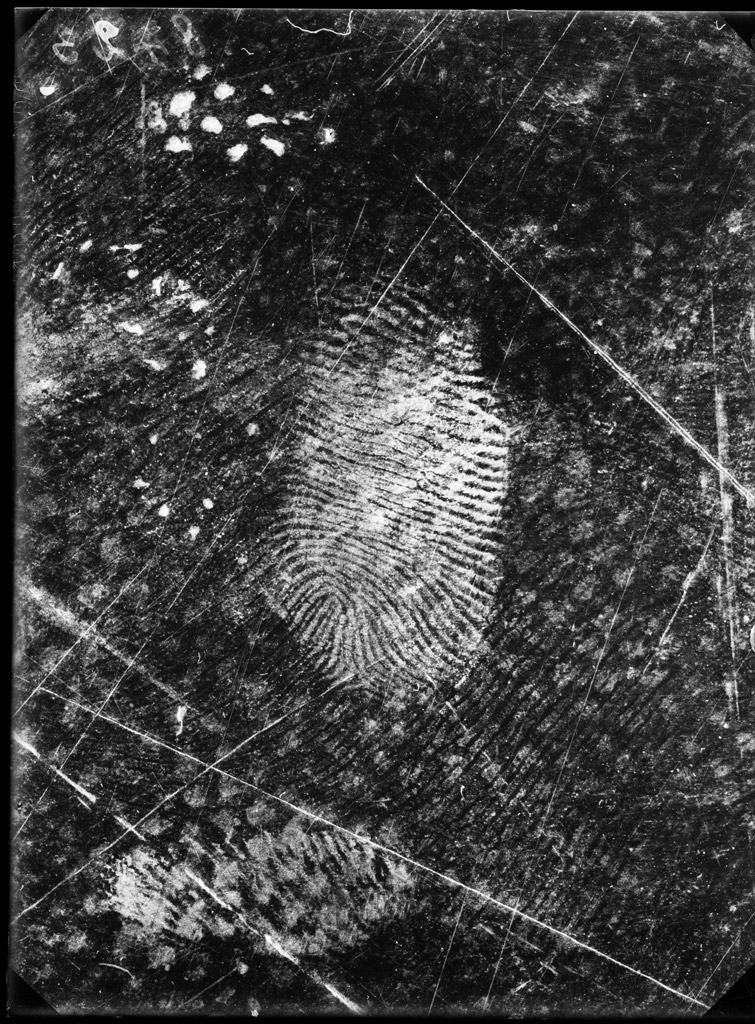

Rodolphe A. Reiss, 25 novembre 1915. Fingerprints on oil cloth, Jost Grand-Chêne robbery case in Lausanne, Vaud, on November 25, 1915

Rodolphe A. Reiss was one of Bertillon’s disciples. He wasn’t a policeman but a chemist and photographer and his work led him to be appointed to the world’s first chair of forensic science in Lausanne in 1906. Reiss was more interested in objects than in people. His method consisted in taking a general view of the crime scene, then in gradually would zooming in and producing photographic close ups that revealed marks, prints and other details that could then be used in forensic analysis.

Just like Bertillon, Reiss had faith in photography, he wrote that ‘A good photograph will often advantageously replace the longest of prosecution speeches.’

The photos shown at the Photographers’ Gallery sometimes look so abstract that i first took them for contemporary artworks.

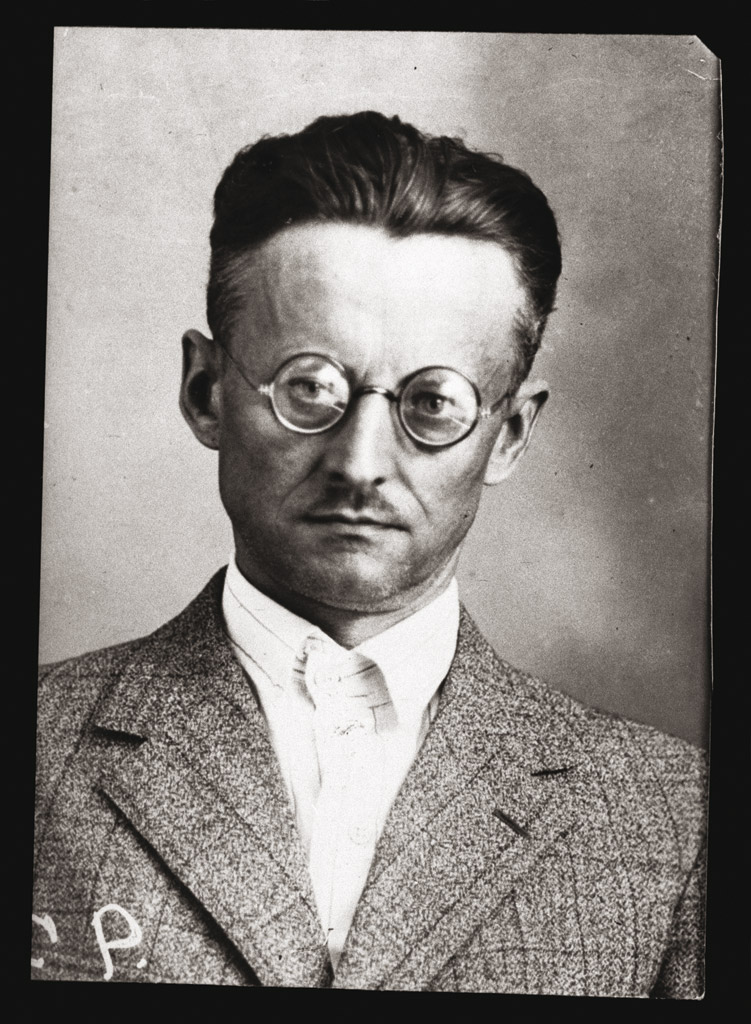

Stanisław Rytchardovich Budkiewicz, Polish, b. 1887 in Łódź. Higher education, VKP(b) member, brigade commissar (political officer), attached to Army Intelligence, officially scientific secretary for the preparation of the Soviet Military Encyclopaedia. Domiciled in Moscow, Pushkin Square 6, Apartment 15. Arrested 9 June 1937. Sentenced to death 21 September 1937. Executed the same day. Rehabilitated 1956. © Central Archives of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation (FSB), Moscow; Archives of International Association Memorial, Moscow

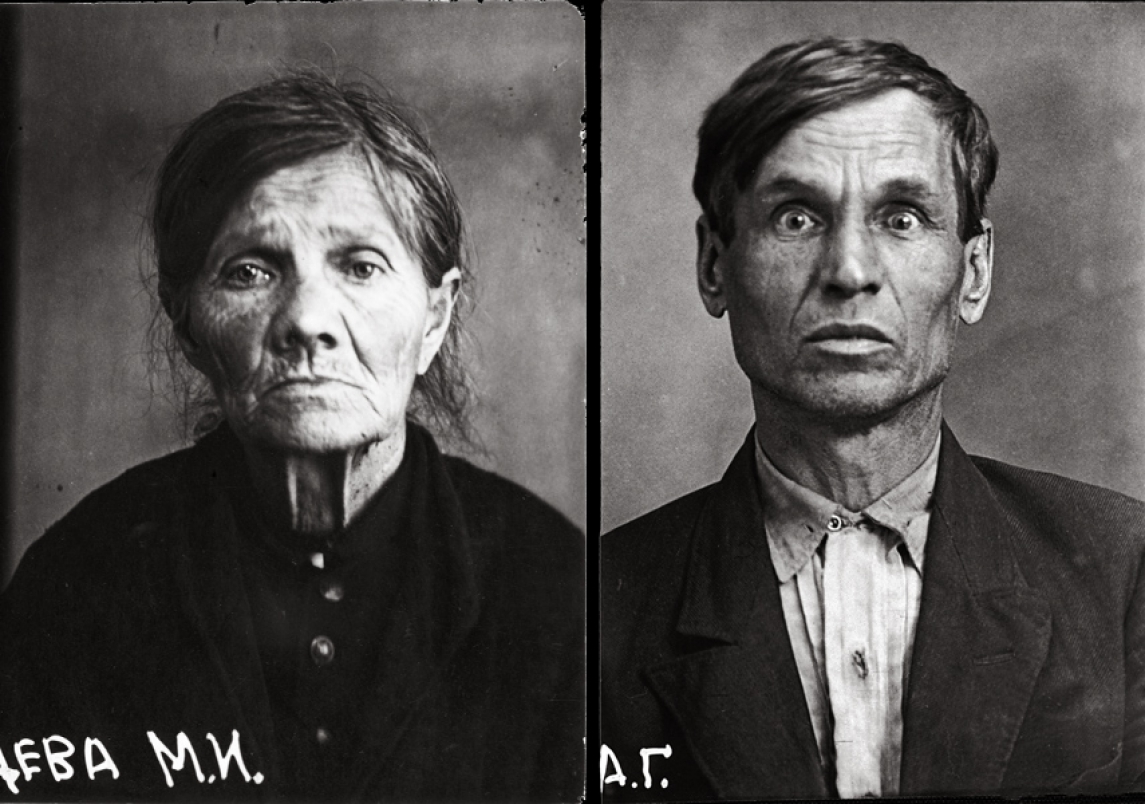

Alekseï Grigorievitch Jeltikov and Marfa Ilinitchna Riazantseva. © Central Archives of the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation (FSB), Moscow; Archives of International Association Memorial, Moscow

From August 1937 to November 1938, nearly 750,000 Soviet citizens were sentenced and shot in the neck, that’s almost 50,000 executions per month. The executions constitute the largest massacre ever committed by a state against its own people and were part of a regime of repression that historians call the Great Terror.

The Politburo of the Communist Party headed by Stalin made official records of the victims before their execution. They were photographed in front and side view against a neutral background, in conformity with the mugshot norms laid down by Bertillon. Ironically, the shots are now used as evidence not of the crimes of the accused, but of those committed by the Stalinist regime.

The defendants before the screenings of the film Nazi Concentration and Prison Camps, 29 November 1945

Courtroom during the screening of Nazi Concentration and Prison Camps, 29 November 1945

On November 29th, 1945, at the hearing of 21 Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg, the prosecution screened a film showing the horrific scenes encountered inside German concentration camps at the liberation. To ensure that the footage would be seen as proof against the Nazis, the Allied cameramen were issued highly specific instructions about how they were to film.

During the trial in Nuremberg, the courtroom was rearranged as a cinema theater, with the screen taking the position normally occupied by the judges, and lighting illuminating the defendants’ faces so that jurors could observe their reactions.

It was the first court case that used a film (titled Nazi Concentration and Prison Camps) as a piece of evidence demonstrating crimes against Humanity.

Richard Helmer, superimposition of Joseph Mengele’s photo portrait and of the skull, 1985. Photograph: Richard Helmer. Photo courtesy of Maja Helmer

Richard Helmer, superimposition of Joseph Mengele’s photo portrait and of the skull, 1985. Photograph: Richard Helmer. Photo courtesy of Maja Helmer

Thomas Keenan and Eyal Weizman, Mengele’s Skull, 2012

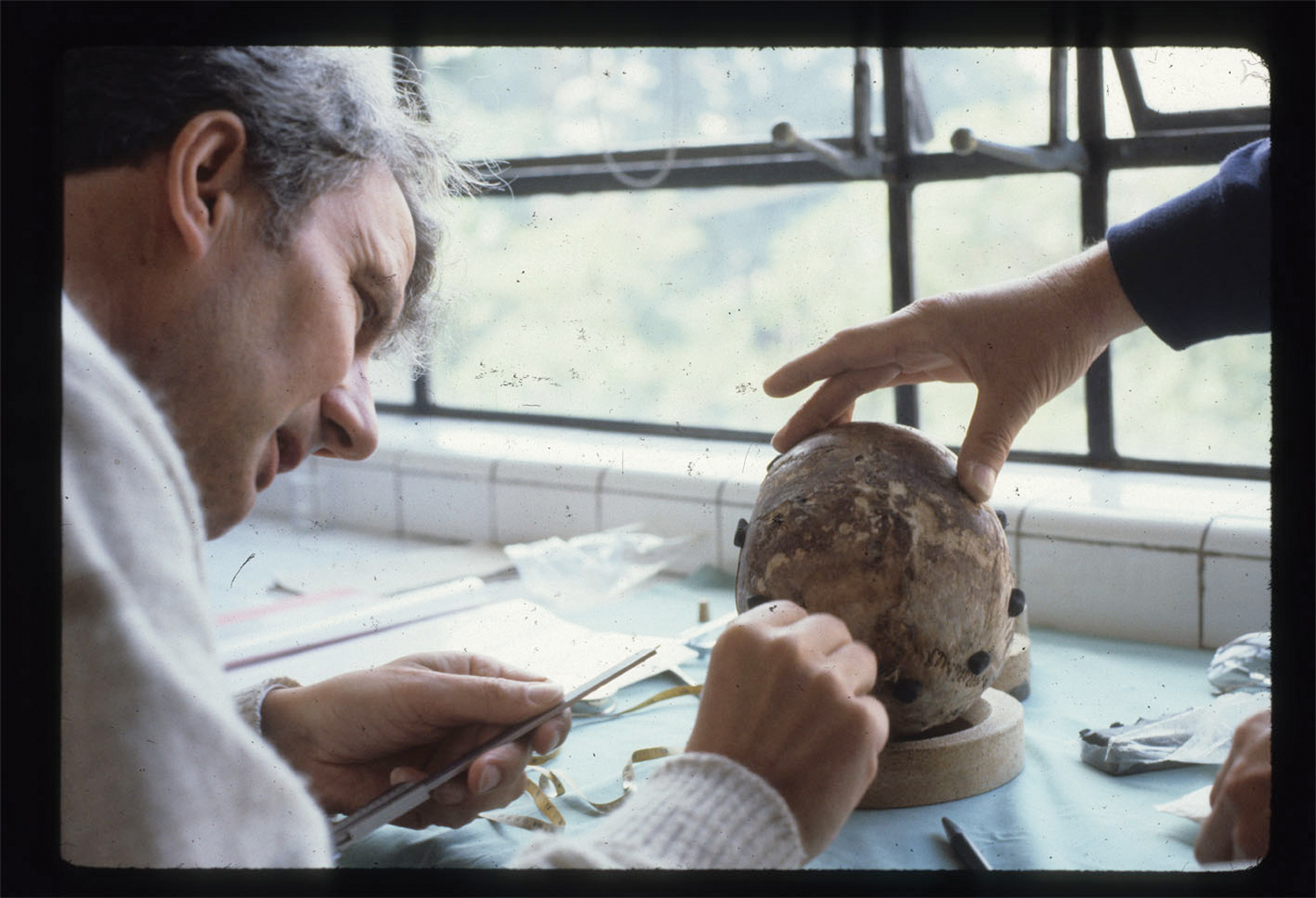

Helmer prepares the skull. Photo Eric Stover, via Forensic Architecture

Nicknamed the “Angel of Death”, Josef Mengele was a doctor in Auschwitz famous for his role in performing experiments on twins and on selecting who among the arriving prisoners would be sent to the gas chambers and who to the camp. He left Auschwitz shortly before the arrival of the liberating Red Army troops and fled to South America, where he managed to elude capture for the rest of his life.

He drowned while swimming off the Brazilian coast in 1979 and was buried under a false name in the cemetery of a small town outside São Paulo. It is only in 1985 that his remains were found, disinterred and analysed for identification.

The technology to extract DNA from bones wasn’t fully developed until the early 1990s so, as part of the investigation to ascertain that these were indeed the remains of the war criminal, German photographer and pathologist Richard Helmer developed a technique which superimposed archive photos of the Nazi over a video feed of the exhumed skull. In the resulting images Mengele’s face emerges out of and dissolves back into his skull, like a ghost, a spectral presence haunting the living. A few years later, DNA testing confirmed that the remains found in Brazil were indeed Mengele’s.

Susan Meiselas, Grace A-South, Koreme, North of Iraq, June 1992

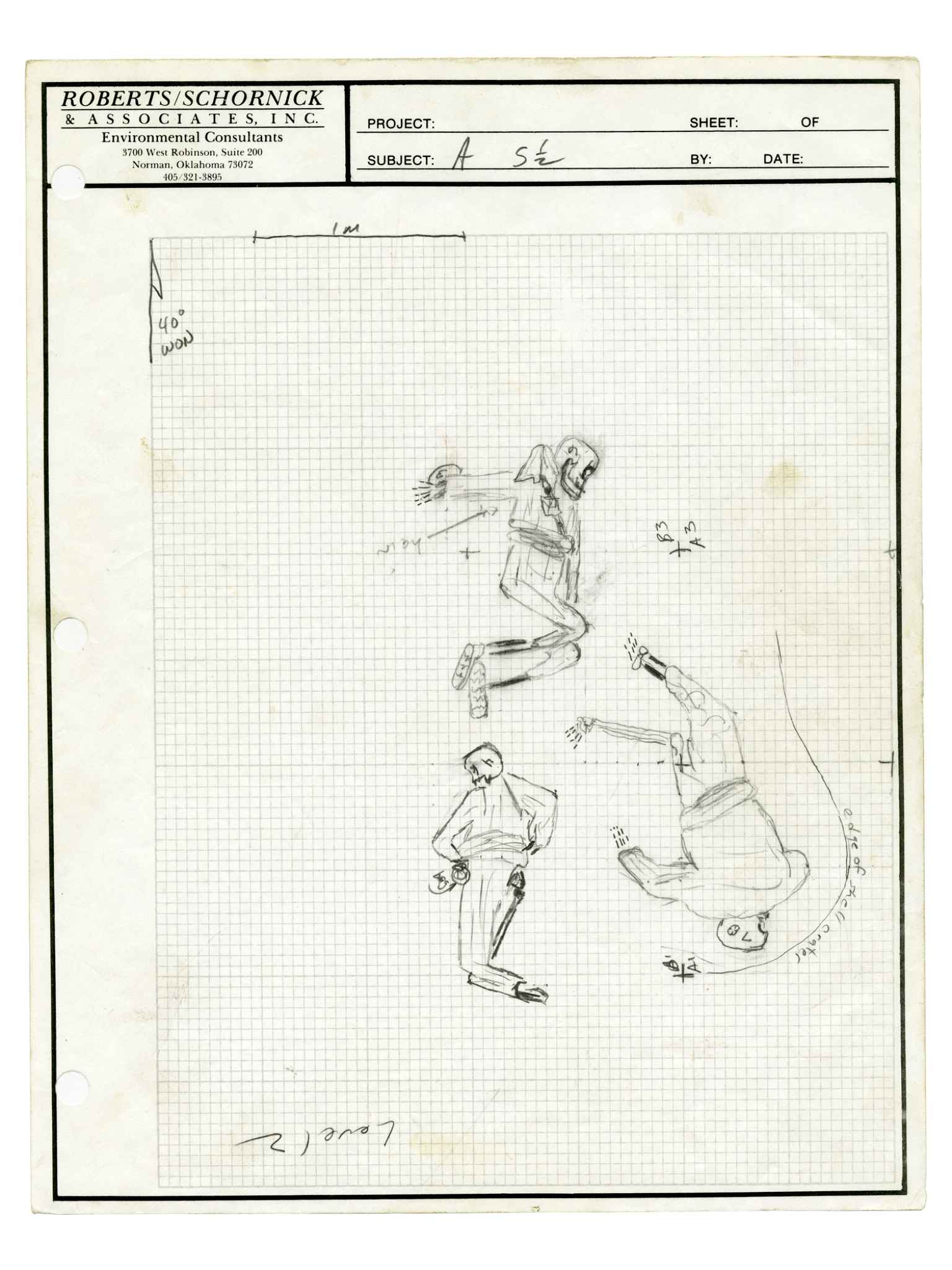

Topographic survey with scale and orientation of the grave A South, level 2, established by James Briscoe, and member of the team Middle East Watch and Physicians for Human Rights, May-June 1992

In 1988, the Iraqi government and army proceeded to destroy thousands of Kurdish villages located in Iraqi Kurdistan. Using a similar pattern throughout the campaign, the Iraqi army first attacked a village then captured its inhabitants and set to systematically demolish their dwellings. The Kurdish village of Koreme serves as a case study of this campaign, showing how the destruction strategies were implemented. In 1992, Middle East Watch and a team of forensic experts exhumed the four mass graves in Koreme.

The images and drawings shown in the exhibition document the forensic archaeological and anthropological investigations used to identify the mass graves. Susan Meiselas, from Magnum Photos, documented the exhumation work. Meanwhile, the content and disposition of the graves were detailed by drawings made by James Briscoe. On the basis of these images and of the experts report, Human Rights Watch and Physicians for Human Rights concluded that these executions constite, at a minimum, crimes against humanity and may even form the basis for a case of genocide.

Fazal Sheikh, al-Türi cemetery, al-‘Araqïb, 9 October 2011. The graves at the center of the cemetery are the oldest ones, they were there before the creation of the State of Israel

al-Türi cemetery, detail n°14 enlarged 5033, RAF series Palestine Survey, 5 janvier 1945. A British Survey of Palestine, 1947

Forensic Architecture was involved in several of the case studies presented in the exhibition. This research laboratory uses various disciplines such as archaeology, engineering and media analysis to investigate the consequences of societal conflicts and human rights violations.

Between December 1944 and May 1945, the UK Royal Air Force surveyed and photographed Palestine from the air. These aerial images provide a precise mapping of the Palestinian territory before the creation of the State of Israel and document the violences against Bedouins. Forensic Architecture examined the archive images and looked for historical evidence of ancient cemeteries which would lend legitimacy to the claims of Palestinian Bedouin families whose ancestors lived in the Negev prior to the existence of the State of Israel and were expelled from their lands in the wake of the 1947 partition plan. Given the low resolution of the images, the graves are little more than tiny, blurry evidence that lie at what Weizman calls the threshold of detectability. By reading such traces out of the image, state representatives and the authors of the Regavim report showed themselves to be committed to an active form of ‘not seeing,’ writes Eyal Weizman.

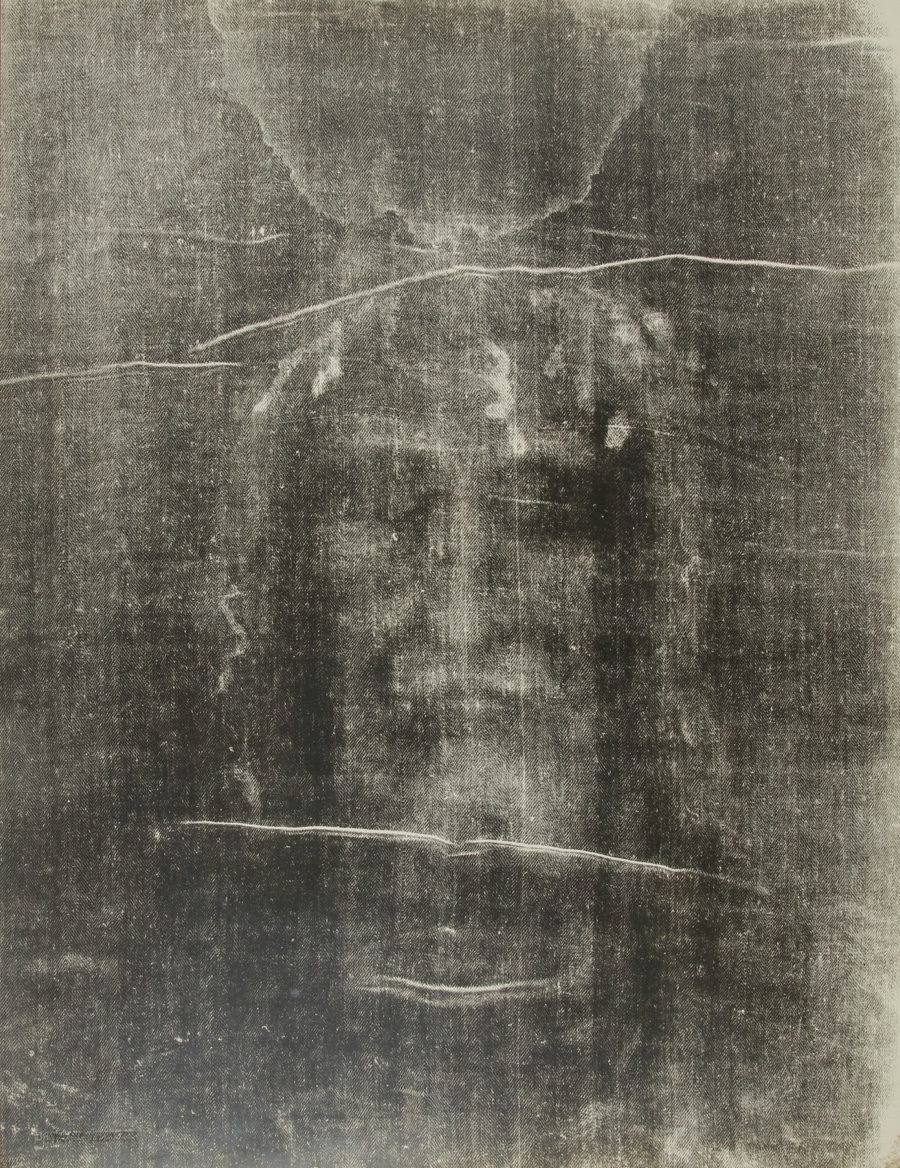

Le Saint Suaire de Turin, negative image. Enlargements by Paul Vignon from photographs taken by Giuseppe Enrie (1931-1933)

If there are photos i was not expecting to ever see at The Photographers’ Gallery it was those of the Shroud of Turin. Even though it has been long established that the piece of linen cloth is not the burial shroud of Jesus of Nazareth, catholics still pack coaches and fly in droves to admire the ‘image of Christ after crucifixion’ when it is exhibited once every few years in Turin.

The shroud is little more than a historical curiosity but it still deserves a place in the gallery as being perhaps the first forensic photograph, even though it was later revealed to be a fake dating back to the 13th or 14th Century.

Burden of Proof: The Construction of Visual Evidence is a stunning and relentlessly engaging show. Don’t miss that one, fellow fans of the macabre!

A few phone pics of the exhibition:

There is more details about each case study in this PDF.

Burden of Proof: The Construction of Visual Evidence remains open until 10 January 2016, at The Photographers’ Gallery, in London.