Thomson & Craighead, stills from October, two-channel installation, 2012. Commissioned by Photoworks © Thomson & Craighead

Thomson & Craighead, stills from October, two-channel installation, 2012. Commissioned by Photoworks © Thomson & Craighead

To be honest, i’d take any excuse to hop on a train and go to Brighton. Two Saturdays ago, it was sunny, i needed a break from the Frieze art fair and the 5th edition of the Brighton Photo Biennial had the kind of theme that makes me buy a train/plane/bus ticket, Agents of Change: Photography and the Politics of Space.

BPB12 explores how space is constructed, controlled and contested, how photography is implicated in these processes, and the tensions and possibilities this dialogue involves. This year’s Biennial provides a critical space to think about relationships between the political occupation of physical sites and the production and dissemination of images.

Agents of Change is a theme that belongs to the moments of economic and political uncertainty we are experiencing today. The exhibitions are at times dark and disturbing but they also demonstrate the role that photography can play in servicing a cause, an agenda, a belief. Whether it is the one of a corporation advertising its products, of a government attempting to enforce new measures or the one of grassroot activists struggling to give another view of a contentious or under-discussed issue.

Omer Fast, 5000 Feet is the Best, still by Yonn Thomas, 2011. Courtesy of the artist, Arratia, Beer, Berlin, and gb agency, Paris, © Omer Fast

Omer Fast, 5000 Feet is the Best, still by Yonn Thomas, 2011. Courtesy of the artist, Arratia, Beer, Berlin, and gb agency, Paris, © Omer Fast

Omer Fast, 5000 Feet is the Best, still by Yonn Thomas, 2011. Courtesy of the artist, Arratia, Beer, Berlin, and gb agency, Paris, © Omer Fast

Omer Fast, 5000 Feet is the Best, still by Yonn Thomas, 2011. Courtesy of the artist, Arratia, Beer, Berlin, and gb agency, Paris, © Omer Fast

Omer Fast, 5000 Feet is the Best, still by Yonn Thomas, 2011. Courtesy of the artist, Arratia, Beer, Berlin, and gb agency, Paris, © Omer Fast

Omer Fast, 5000 Feet is the Best, still by Yonn Thomas, 2011. Courtesy of the artist, Arratia, Beer, Berlin, and gb agency, Paris, © Omer Fast

The most compelling work in the biennial for me was Omer Fast‘s video about drone surveillance and warfare.

The film is based on two meetings with the operator of a Predator drone sensor. The operator had been based in the desert outside of Las Vegas for 6 years while he was working for the U.S. military. The artist met him in Vegas where he was looking for a job as a casino security guard.

But Fast’s film is not a documentary with news footage and testimonies from real protagonists of the events. Instead, the stories are told by an actor cast as the drone operator. His narration is moving, informative and sometimes even humorous.

The operator is sitting in a nondescript hotel room. He unenthusiastically recalls his missions in Afghanistan and Pakistan, unsure that the audience will ever understand what he went through. The soldier never set foot in the countries where the unmanned plane he piloted fired at civilians and militia from the optimum height of 5000 feet.

At times, the ex-soldier seems to ramble, using unrelated stories as metaphors. The most striking of the anecdotes he recalls is the one of an American family that takes the road for ‘a long drive’ (see the video below.) To leave town, they have to go through security checkpoints and present documents to the “occupying forces,” which are depicted as Asians. It’s a complete reversal of the situation in which Americans get to see how much a war in their own turf would affect daily life. Except that the U.S. is at war too but for most citizens, only from a distance. The drone operator never leaves the material comfort of his own country to fight in foreign countries, most of the American population never gets bombed or fired at by drones.

Omer Fast, 5,000 Feet is the Best

The dark world of the U.S. military goes far beyond the drones and bombings as Geographies of Seeing, the show on view at The Lighthouse, convincingly demonstrates. But I’m going to try to keep this one short because i seem to be unable to let a month pass without writing about the work of artist and geographer Trevor Paglen.

The exhibition is focused on two series of photos that document the secret activities of the U.S. military and intelligence agencies. The first one is The Other Night Sky which tracks and documents classified American satellites in Earth orbit. With the help of a network of amateur “satellite observers” and of a specially designed software model able to describe the orbital motion of classified spacecraft, Paglen calculated the position and timing of overhead reconnaissance satellite transits. He then photographed their passage using telescopes and large-format cameras.

The second body of work shown at The Lighthouse is Limit Telephotography. For this series, Paglen used high powered telescopes to picture the “black” sites, a series of secret locations operated by the CIA. Often outside of U.S. territory and legal jurisdiction, these locations do not officially exist, they range from American torture camps in Afghanistan to front companies running airlines whose purpose is to covertly move suspects around.

Well, that wasn’t so short but i do have to confess that i merely copy/pasted texts i wrote about Paglen’s work a few months ago.

Trevor Paglen, They Watch the Moon, 2010, C-print © Trevor Paglen, Courtesy of Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco

Trevor Paglen, They Watch the Moon, 2010, C-print © Trevor Paglen, Courtesy of Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco

KEYHOLE 12-3 (IMPROVED CRYSTAL) Optical Reconnaissance Satellite Near Scorpio (USA 129), 2007. Courtesy of Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne, and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco, © Trevor Paglen

KEYHOLE 12-3 (IMPROVED CRYSTAL) Optical Reconnaissance Satellite Near Scorpio (USA 129), 2007. Courtesy of Galerie Thomas Zander, Cologne, and Altman Siegel Gallery, San Francisco, © Trevor Paglen

A couple of years ago, Edmund Clark traveled to Guantanamo to document three experiences of home: the home of the American community at the naval base; the camp complex where the detainees have been held; and the homes where former detainees, never charged with any crime, find themselves trying to rebuild lives.

With the body of work presented at the Biennial, Clark pursues further his interest in structures of control and incarceration. In December 2011, the photographer was the first artist to be granted access to a house in which a person suspected of terrorist related activity had been placed under what the UK calls ‘a Control Order.’

The 2005 Prevention of Terrorism Act granted the Home Office the power to relocate any controlled person to a house in an alien town or city and impose restrictions and conditions, similar to house-arrest. So far, 48 people have been made subject to a Control Order.

Clark could not reveal the identity of the controlled person nor the location of their house. He also had to pre-register all digital equipment and to accept restrictions on how the equipment could be used. All his photos were then screened by the Home Office and the controlled person’s lawyers.

The series is still a work in progress and i wish i could be in England on Thursday, 1 November 2012 because the photographer will be discussing his work at The Lighthouse.

Edmund Clark, Control Order House, 2011. © Edmund Clark

Edmund Clark, Control Order House, 2011. © Edmund Clark

Edmund Clark, Control Order House, 2011. © Edmund Clark

Edmund Clark, Control Order House, 2011. © Edmund Clark

Edmund Clark, Control Order House (view of the exhibition space)

Edmund Clark, Control Order House (view of the exhibition space)

The images screened on Thomson & Craighead‘s October installation are brutally shocking. Maybe because even when the videos were shot at the other end of the world, they echo the social and economic inequalities we are experiencing in Europe (or wherever you’re living right now.) The film installation creates a portray of the Occupy protests by drawing on amateur footage that the activists uploaded on YouTube. Below the video screen is a luminous compass that points to the locations where the videos were originally filmed, adding the precise distance of the location of the footage from the viewers. The piece examines the relationship between geographical space and the Internet: the role online organisation plays in shaping offline activism.

Thomson & Craighead, October (view of the exhibition at Space @ Create)

Thomson & Craighead, October (view of the exhibition at Space @ Create)

The exhibition of photographer, journalist, researcher and political activist John “Hoppy” Hopkins also document peace marches, protests and underground movements from the inside but this time in and around London in the 1960s. Some 50 years are separating the Occupy videos from Hopkins’ photos but both show the power of the image when it comes to telling the activists’ side of a news story.

John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, Speakers’ Corner, 1964. © John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins

John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, Speakers’ Corner, 1964. © John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins

John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, Homeless March St Paul’s

John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, Homeless March St Paul’s

John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, A CND protest in West Ruislip

John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, A CND protest in West Ruislip

There’s so much more to say about this biennial. There are many other exhibitions i don’t have the space to mention here. And talks, tours, workshops. I’ll close my superficial review of the biennial with random photos of the shows and of the city.

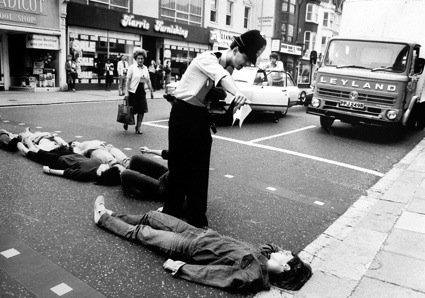

The Argus Archives, Anti-nuclear protestors block the road by lying down, holding up traffic until police were able to remove them, London Road, 1982. ©The Argus

The Argus Archives, Anti-nuclear protestors block the road by lying down, holding up traffic until police were able to remove them, London Road, 1982. ©The Argus

I forgot to mention Whose Streets?, an outdoor show located on one of the city’s public square that looks at the archive of local newspaper The Argus, to extract images that depict Brighton as a contested political space for protest. From the late 70s to the present.

The Argus Archives. Exhibition in the streets of Brighton

The Argus Archives. Exhibition in the streets of Brighton

The Argus Archives, The far-right National Front march through Brighton. The party’s membership had decreased significantly by the early 1980s. Castle Square, 1981. ©The Argus

The Argus Archives, The far-right National Front march through Brighton. The party’s membership had decreased significantly by the early 1980s. Castle Square, 1981. ©The Argus

Jason Larkin, ‘Untitled #2’, Cairo Divided, 2011, © Jason Larkin

Jason Larkin, ‘Untitled #2’, Cairo Divided, 2011, © Jason Larkin

Theo Simpson, from Four Versions of Three Routes by Preston is my Paris, 2012. © Theo Simpson

Theo Simpson, from Four Versions of Three Routes by Preston is my Paris, 2012. © Theo Simpson

The 2012 Brighton Photo Biennial is curated by Photoworks Head of Programme, Celia Davies and Programme Curator, Ben Burbridge. Brighton Photo Biennial is free and it is up all over the city of Brighton until 4 November 2012.

Previously: Exhibition tip – Omer Fast at the Netherlands Media Art Institute,

Architecture of Fear – a conversation with Trevor Paglen and Guantanamo: If the Light Goes Out by Edmund Clark.