The Concrete Dragon: China’s Urban Revolution and What It Means for the World, by Thomas J. Campanella, an associate professor of urban design and planning at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a visiting professor at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

The Concrete Dragon: China’s Urban Revolution and What It Means for the World, by Thomas J. Campanella, an associate professor of urban design and planning at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a visiting professor at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Publisher Princeton Architectural Press says: China is the most rapidly urbanizing nation in the world, with an urban population that may well reach one billion within a generation. Over the past 25 years, surging economic growth has propelled a construction boom unlike anything the world has ever seen, radically transforming both city and countryside in its wake. The speed and scale of China’s urban revolution challenges nearly all our expectations about architecture, urbanism and city planning. China’s ambition to be a major player on the global stage is written on the skylines of every major city. This is a nation on the rise, and it is building for the record books.

China is now home to some of the world’s tallest skyscrapers and biggest shopping malls; the longest bridges and largest airport; the most expansive theme parks and gated communities and even the world’s largest skateboard park. And by 2020 China’s national network of expressways will exceed in length even the American interstate highway system. China’s construction industry, employing a workforce equal to the population of California, has been erecting billions of square feet of housing and office space every year. But such extensive development has also meant demolition on a scale unprecedented in the peacetime history of the world. Nearly all of Beijing’s centuries-old cityscape has been bulldozed in recent years, and redevelopment in Shanghai has displaced more families than 30 years of urban renewal in the United States. China’s cities are also rapidly sprawling across the landscape, churning precious farmland into a landscape of superblock housing estates and single-family subdivisions laced with highways and big-box malls. In a mere generation, China’s cities have undergone a metamorphosis that took 150 years to complete in the United States.

The image which opens the first chapter is Wu Ping’s Stubborn Nail, a picture that has toured the online sphere and epithomizes the main characteristics of the book. Together with her husband Wu Ping refused to move out of her house in Chongqing and make way for local property development. During three years, the house stood out isolated, the husband even built staircases with his nunchakus from the bottom of the over ten-meter-deep construction site. All in vain.

Image by Sean Gallagher

Image by Sean Gallagher

Whether it’s Chinese art overkill or the Olympic events, we’re all force fed bits of China these days. Publishers are churning out books about China so relentlessly that it’s getting hard to discern which volume is merely surfing on the sino-wave and which one is genuinely well-documented and informative. A tour in architecture, art and design bookshops shows that the theme of urban revolution is particularly popular. After all, as the author found out, China counts nearly 700 cities, compared to less than 200 in the late ’70s. The U.S. has 9 cities with a million or more inhabitants, China has more than one hundred.

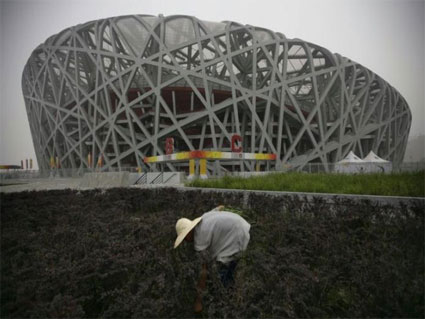

Bird’s Nest (image La Repubblica)

Bird’s Nest (image La Repubblica)

Inside the V.I.P. entrance of the National Stadium, aka The Bird’s Nest (From a slideshow at The New Yorker)

Inside the V.I.P. entrance of the National Stadium, aka The Bird’s Nest (From a slideshow at The New Yorker)

How can we resist? The stories surrounding the revamping of Beijing in preparation for the Olympics beat your favourite soap opera on the dramas and suspense front. The Bird’s Nest, neighbour of the Water Cube the other Olympic superstar, is every bit as gorgeous in real as it appears on glossy papers. That didn’t prevent superstar Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, who collaborated with Herzog & de Meuron on its design, to slam the amount of propaganda that comes with the sport event (video), there’s Zhu Pei brilliant computer circuitry-inspired Digital Beijing and brand new shopping malls and massive modern apartment blocks but they come with a sometimes questionable out with the old, in with the new approach.

Image by Sean Gallagher

Image by Sean Gallagher

The new Beijing is a mesmerizing playground for architectural innovation where migrant workers are whisked away just before the opening of the event they’ve helped prepare and people have been Olympic evicted (most of them have received financial compensations but The Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions estimated that, over an eight-year period leading up to this summer’s games, up to 1.5 million people have been moved from their Beijing homes because of the Olympics). Oh! and the selection of Albert ‘son of Hitler’s architect‘ Speer as the head of Beijing’s new urban plan had tongues wagging, no matter how respectable his career might be.

Digital Beijing. Photo Iwan Baan

Digital Beijing. Photo Iwan Baan

Given the amount of ink spilled over the Chinese speedy urbanization case, I think i’ve been lucky with The Concrete Dragon. The book is packed with impressive figures which could be more or less summed up by the statement that the Chinese do it bigger, bolder and so much faster. All the while knowing that nothing can be compared to what China is living these days, Campanella draws many parallels with the U.S. of a century ago when skyscrapers rose from the ground and spirits were dazed and euphoric about what the future would bring.

Unlike most commentators who (understandably) focus on Beijing and on the past five years, Campanella travels back in times and narrates the Beijing as it was before Mao put a drastic and heavy hand on the traditional urban fabric. But the author also recalls the urban story of other cities like Shanghai and Shenzhen, visits the incredibly popular theme parks, takes pictures of a replica of Piazza San Marco in South China Mall, the largest mall in the world. He reflects on the influence of foreigners, on the destruction of the architectural patrimony and more importantly the author comments on the global and local impact of these transformations on the environment and the social fabric. Being bolder, faster and bigger comes also with a terrible human costs.

However, Campanella sees beyond the stereotypes that the typical Westener often has about China. He refrains from quick judgments, seems to genuinely admire China and has still buckets of hopes for what the future might bring, especially on the ‘going green’ front.

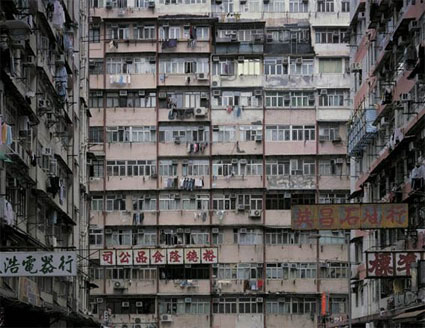

Architecture of Density by Michael Wolf

Architecture of Density by Michael Wolf

What makes it particularly precious for me is that every single photo biennale, photo festival or major exhibition about urbanism i visit these days features large scale photographies of jaw-dropping Chinese cityscapes. But these images always appeared to be a bit out of context, The Concrete Dragon finally gives some sense to these images.

Hong Kong, Corner Houses by Michael Wolf

Hong Kong, Corner Houses by Michael Wolf

Image on the homepage from the Solidified Memories series by Boris Austin.

Related: Global Cities at Tate Modern.

The Chinese Far West, Get It Louder (Part 1, China), China China China China !!! Chinese contemporary art beyond the global market, Neural magazine special China, China Now at the Cobra Museum, Beijing’s “hutong” destruction, 798 art district in Beijing.