Previous episodes of Bodily Matters: Human Biomatter in Art: Part 1. The blood session; Part 2. At the morgue; Part 3: On expendable body parts and Part 4. On skin and hair.

Part five (and i can’t believe how slow i am) of the notes i took during Bodily Matters: Human Biomatter in Art. Materials / Aesthetics / Ethics, a symposium that took place a month ago at University College London. The outstanding event explored how artists use the human body not merely as the subject of their works, but also as their substance.

Session 5. The Extended Body: Biomedicine, Micromatter & the Transhuman was the most eclectic and unpredictable one. It investigated issues as diverse as the use of forensic methodologies in art, the presence of human cells outside of the body and the possible role of bacteria in creativity.

Mat Collishaw, Bullet Hole, 1988

Marc Quinn, Self, 1991

In his paper titled The Northern Way to Medical Display: The clinical methodology of Glaswegian artists in the 1990s and Christine Borland’s skeleton-works, Dr. Diego Mantoan (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Department of Philosophy & Cultural Heritage) looked at the different attitudes towards the use of clinical materials in the UK artworld in the 1990s.

The 1990s London art scene dominated by young British artists and their provocative approach to the use of human biomatter has long caused scholars to neglect the presence in the United Kingdom of different ways to treat the display of human remains or medical samples in art. Works such as Marc Quinn’s Self (1991), having the author’s own blood in a plaster cast, or Mat Collishaw’s framed images for Freeze (1988), adopting blown-up autopsy stills, appear rather centred on the public effect they would cause, once the viewer is aware of the material used.

During the YBA years, the only real art counterpart to London was Glasgow, in particular the artists who studied at the Environmental Art Department set up by David Harding at Glagow School of Art. Douglas Gordon and Christine Borland were among the first graduates from the course. Their approach to the use of human biomatter and clinical display was radically different from what Londoners were doing. For David Hardling, “the Context is half the work” and the ethos was reflected in the way Glasgow graduates treated biomatter. The Northerns not only engaged with the medical history and the tradition of clinical display but they also followed scientific protocols when dealing with the use of body parts in artworks.

Douglas Gordon, 24 Hour Psycho (extract), 1993

Douglas Gordon became known in the 1993 with 24 Hour Psycho which as its title clearly indicates is a slowed-down version of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 film hallmark movie. The work can be seen as autopsy of a hallmark movie.

Douglas Gordon, Trigger Finger, 1996

After that work, Gordon spent 3 years researching found footage, especially medical footage from the 20th century. He wanted to breathe new life into them, to put non artist material into a context that would make it artistic, playing with ways of showing the material (fast forward, slow down, blow up the images, etc.) and giving it new aesthetic quality. He went to the archives of the Wellcome Trust and came back with 4 series of works that use clinical footage related to traumatic consequence of World War II, especially psychological disorders such as schizophrenia.

One of them was Head, a video installation showing a head which displayed signs of life right after it had been severed. The work echoes a scientific experiment done in 1905 by Dr Gabriel Beaurieux. The French doctor witnessed that the severed head of a guillotined murderer called Henri Languille remained responsive for some time after being separated from the body.

The eyelids and lips of the guillotined man worked in irregularly rhythmic contractions for about five or six seconds. [After several seconds], the spasmodic movements ceased… It was then that I called in a strong, sharp voice: “Languille!” I saw the eyelids slowly lift up, without any spasmodic contractions – I insist advisedly on this peculiarity – but with an even movement, quite distinct and normal, such as happens in everyday life, with people awakened or torn from their thoughts. Full text in guillotine.dk.

However, Gordon realized that the images of his video were too powerful and that he had to draw a line:

“I showed Head only once, in Uppsala; I showed it never again, because i was too shocked by the images. I think it worked, but it was very hard.” Douglas Gordon, interview by Hans Haase, 1999.

Maybe that’s why i couldn’t find any image of the work online.

Christine Borland, After a True Story: Giant & Fairy Tales, 1997. Photo Glasgow Museums

The skeleton of the 7.5 feet (230 cm) tall Byrne displayed at the Royal College of Surgeons of England in London (middle of this image.) Photo: Paul Dean (StoneColdCrazy) via wikipedia

Another artist from the Glasgow school who engaged by bodily matters was Christine Borland. The artist used clinical material (in particular human bones, skulls and skeletons) and clinical methodologies in her exploration of how to display forensic science and medicine topics.

The first project featuring biomatters was After a True Story: Giant & Fairy Tales.

The installation features two skeletons. One belonged to ‘Irish giant’ Charles Byrne, the other to “Sicilian Fairy” or “Sicilian Dwarf” Caroline Crachami. Clay casts of the original skeletons, kept at the Royal College of Surgeons, were used to leave traces in dust upon glass shelves. The skeletons were then removed and light is shone through the shelves represent the human bodies in their absence

Their individual stories of the people and the exploitation of their bodies (both while living and after their death) is detailed in the book, The Harmsworth Encyclopaedia, which lies open as part of the installation.

The piece reflects Borland’s interest in how scientists work with human remains in a way that can disregard the individuals’ identities and personal values.

Christine Borland, From Life, 1994. Photo: David Allen/Christine Borland/Simon Starling

Christine Borland, From Life, 1994. Photo: David Allen/Christine Borland/Simon Starling

Another of Borland’s works, From Life, consisted in a forensic reconstruction of a missing woman. She set out to purchase a skeleton (a task far more difficult than expected) and asked a crime scientist specialized in osteology to help her uncover the identity of the skeleton. Based on the forensic reconstitution, the artist made a bronze cast of the head. Her rebuilding of the missing woman aimed at giving a personality and identity back to the anonymous remains.

With that work, Borland also realized that she had reached a point where she went too far and she stopped working so intimately with body matters.

Christine Borland, Family Conservation Piece, 1998. Photo: The Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, University of Glasgow

The heads of Family Conservation Piece were cast from skulls found in the Anatomy Department of the University of Glasgow. They are made from fine bone china and decorated with colours and motifs that recall eighteenth century style porcelain. The work was originally made for an exhibition in Liverpool and the use of bone china pointed to the city’s history as a producer of china but it was also meant to evoke its role in the Slave Trade.

The works of Borland and Gordon are typical of the almost scientific method of the Glasgow school. What the artists also have in common is that at some point during their engagement with medical material they became aware that they might have gone too far. They were ready to take a step back in order to preserve the dignity of the individuals behind the often anonymous bodily remains.

Henrietta Lacks, circa 1945–1951. Photo via nbc

In her paper HeLa: Speculative Identity – On the ‘Survival’ of Henrietta Lacks in Art, Maria Tittel, PhD candidate (Universität Konstanz, Literature Arts Media), looked at two artworks that work with the DNA material of Henrietta Lacks.

Tittel writes in her abstract: Those artworks pose urgent ethical questions concerning the relation between artistic work and scientific research. Which aesthetical and ethical aspects are touched in both fields, respectivley, while using human biomatter as material for (art) work and what are the differences?

Medical researchers use “immortal” cells to study how cells work and how diseases can spread and be treated. These laboratory-grown human cells can grow indefinitely, be frozen for decades and shared among scientists for experiments. The first immortal human cell line was created in 1951 using a tissue sample taken from a young black woman with cervical cancer. Called HeLa cells, the cells were the first ones that could be cultivated outside the body. They quickly became invaluable to medical research and are at the origin of many scientific landmarks, including cloning, gene mapping, developing the polio vaccine and in vitro fertilization.

The donor remained a mystery for decades. HeLa are actually the initial letters of the donor’s name, Henrietta Lacks. Because the cells from her tumor were taken without the knowledge or consent of either the woman or her family, the HeLa cells raise a number of issues related to ethics in biotechnology and to the rights of Afro Americans (who in the early 1950s were different from the rights of white Americans.)

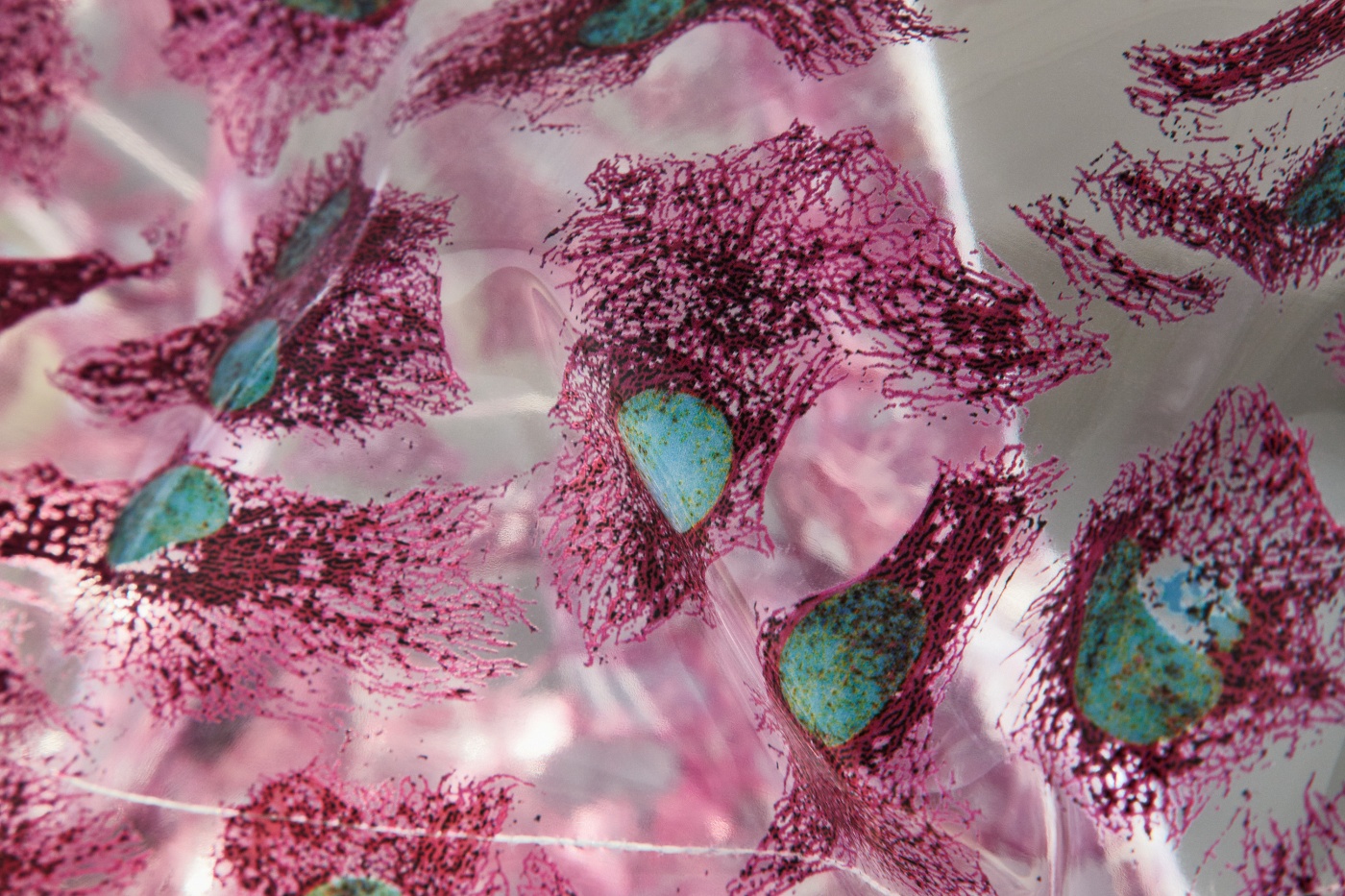

Aleksandra Domanović, HeLa on Zhora’s coat, 2015. Photo: Achim Hatzius

Aleksandra Domanović, HeLa on Zhora’s coat, 2015 (Detail.) Poto: Achim Hatzius

The first work discussed by Tittel was HeLa on Zhora by Aleksandra Domanović. The raincoats are covered in patterns that seem to be abstract but are actually based on medical images of HeLa cells. As for Zhora, she was a replicant in Blade Runner who searched for immortality but died on her way to find it.

The work explore the blurring boundaries between life (the immortal ones of the cells) and death, between the body and the self.

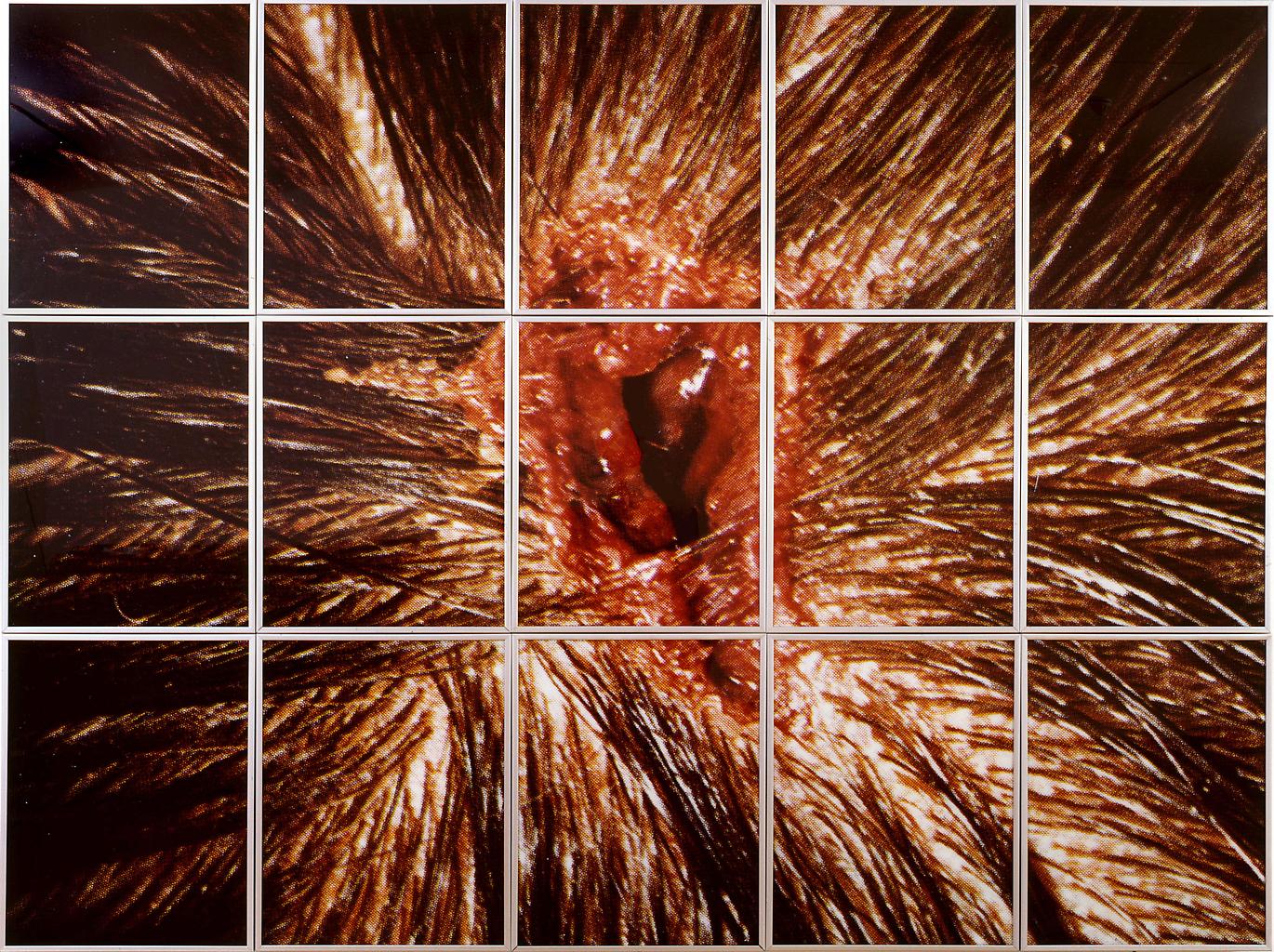

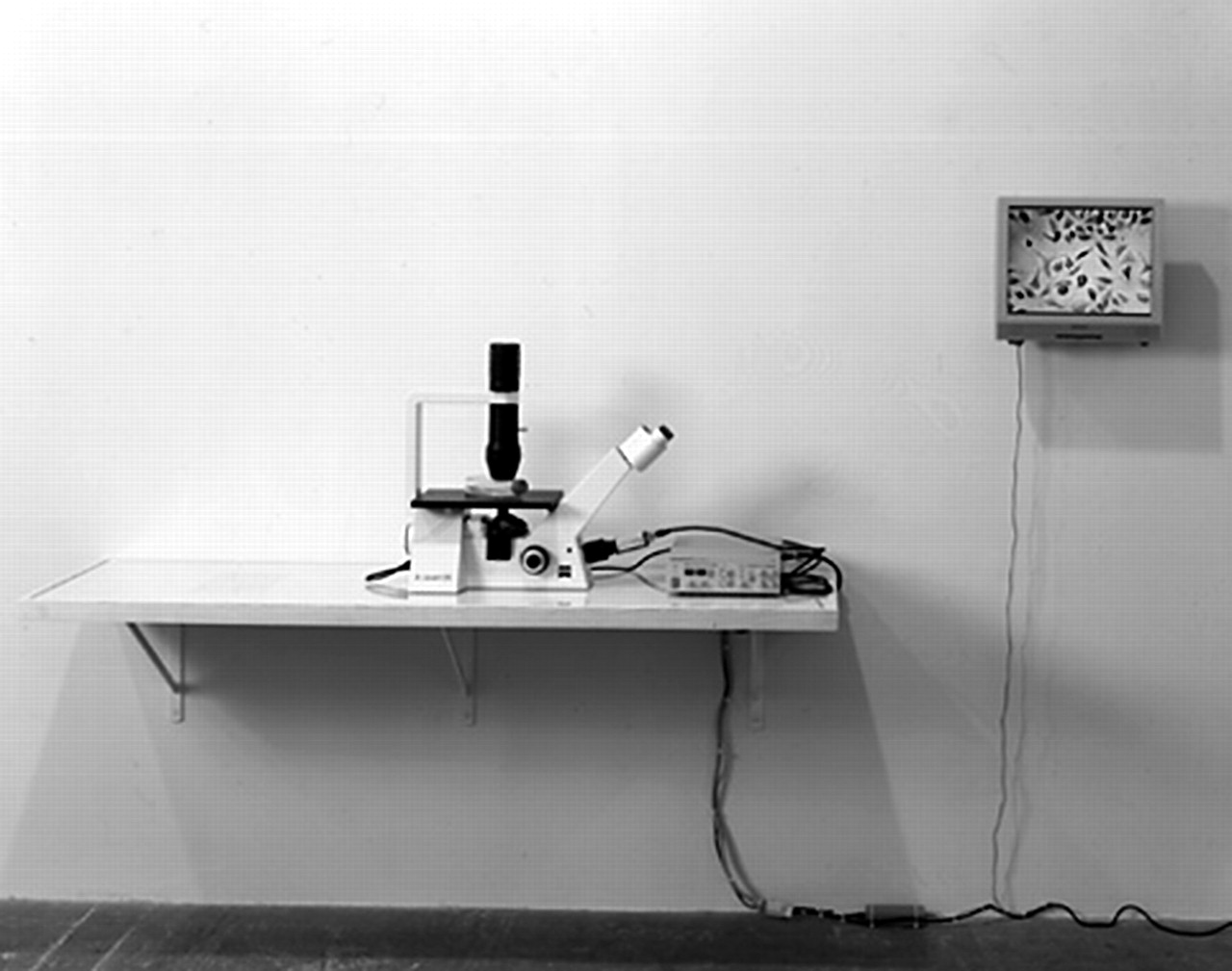

Christine Borland, HeLa, 2001. Photo: Medical Humanities

The other work explored in the presentation was Christine Borland’s HeLa installation which features a Petri dish put under a microscope. The live images of the HeLa cells quickly multiplying in the petri dish are relayed to a screen.

While in a biomedical research lab in Dundee, Borland became interested in the HeLa cells and realised that many of the researchers didn’t know anything about the origin of the material they were using in their work.

Similarly, the text that accompanies the installation is not very specific. The visitor is left wondering what the title “HeLa” stands for, where the cells come from, what the medical image is about. With this piece, Borland seems to be emphasizing the aesthetic aspect of medical imaging that often doesn’t take into account the background of the cell culture used.

Katy Connor, Untitled_Force (Laser engraved porcelain tiles), 2011

In her ‘Untitled_Force’: Becoming Nylon through 3D Print paper, Katy Connor, PhD candidate & visual artist (Bournemouth University, Centre for Experimental Media Research) presented Untitled_Force, a series of digital print and sculptures based on Atomic Force Microscope scans of her own blood.

Despite its microscopic scale, images from this process visually reference satellite photographs of the Earth’s surface, becoming body, landscape, and media simultaneously. Highly magnified, the data is also given form through a series of additive processes; layer upon layer of sintered nylon, these disarticulated fragments lending material shape to these intimate interactions, these entanglements between body and machine.

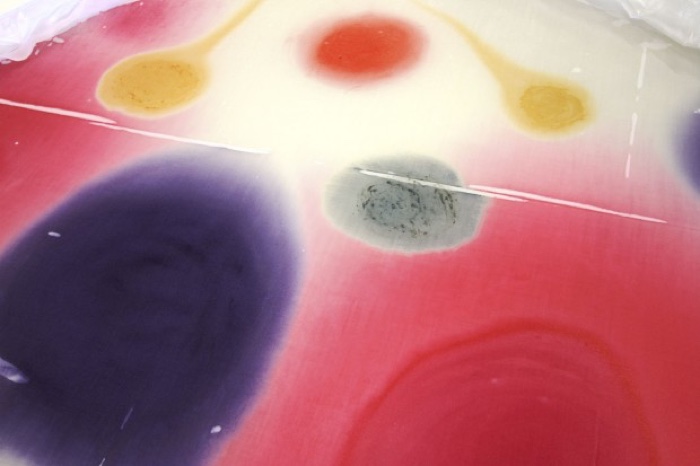

Bacterial War Games, Incubation Day 2. Photo: Simon Park

In The Extended Self: visualizing the human bacterial symbiont, microbiologist Dr. Simon Park (University of Surrey, Department of Microbial Sciences) took us on a tour of his adventures in microbiology and art (they are also documented on his blog exploringtheinvisible.)

Park wrote in his abstract: Whilst often ignored, our bacterial aspect (the microbiome), containing 100 trillion normally invisible cells, and 2 million microbial genes, dwarfs our eukaryotic genetics, biochemistry, and physiology. Moreover, many recent studies have begun to reveal the huge impact of the microbiome in terms of our health, its ability to modulate our own behavior and moods, and even its influence on our ability to learn. This paper will explore my practice in terms of the various processes and artworks that I have developed/made in order to reveal this usually hidden but vital aspect of self. These projects range from simple microvideos capturing the movement and activity of my own microflora, to a method for directly projecting the microbiome into the macroscopic world, and finally to a series of unique and autogenic self portraits that result directly from the activity of my microbiome.

First Park quickly defined a few key terms for us:

The microbiome is the aggregate of microorganisms that reside on or inside the body.

The human microbiome is the genomes of the microbiota (microbiomal genes outnumber our human genes by 1 to 100.)

The holobiont is the host plus all its microbial symbionts, including transient and resident members.

In 2000, the microbiologist got infected by a bacteria and was treated with heavy antibiotics. His microbiome was destroyed in the process. He says that he lost at least half of what was once him. A full microbiome eventually returned but it was not the same as the original one. This new microbiota changed Park forever, both physically and mentally.

Park now suffers from illnesses he never had before. Even his mood changed. Bacteria in the gut can influence the production and delivery of neuroactive substances such as serotonin. Mice that are born in germ free environment, for example, have 60% less serotonin.

Simon Park and Heather Barnett, Cellfies: cellular self portraits

Park then decided to look at what he had lost and started collaborating with artist Heather Barnett to develop a series of art & science projects. In one of them, Cellfies, they used a powerful (DIC) microscope to make selfies of themselves at a cellular lever. The microscope reveals nucleated human epithelial cells, bacteria from the microbiome, and cells from the human immune system.

In other works, they used bacterias as inks, as if they were living paints that move around and interact with each other. Each bacteria have their own characteristics. Some are quiet, others move aggressively. The pieces that the scientist and the artist developed together make visible the complexity of the microbiome: it is dynamic, changes everyday and it seemed natural to Park that it could play a role in art.

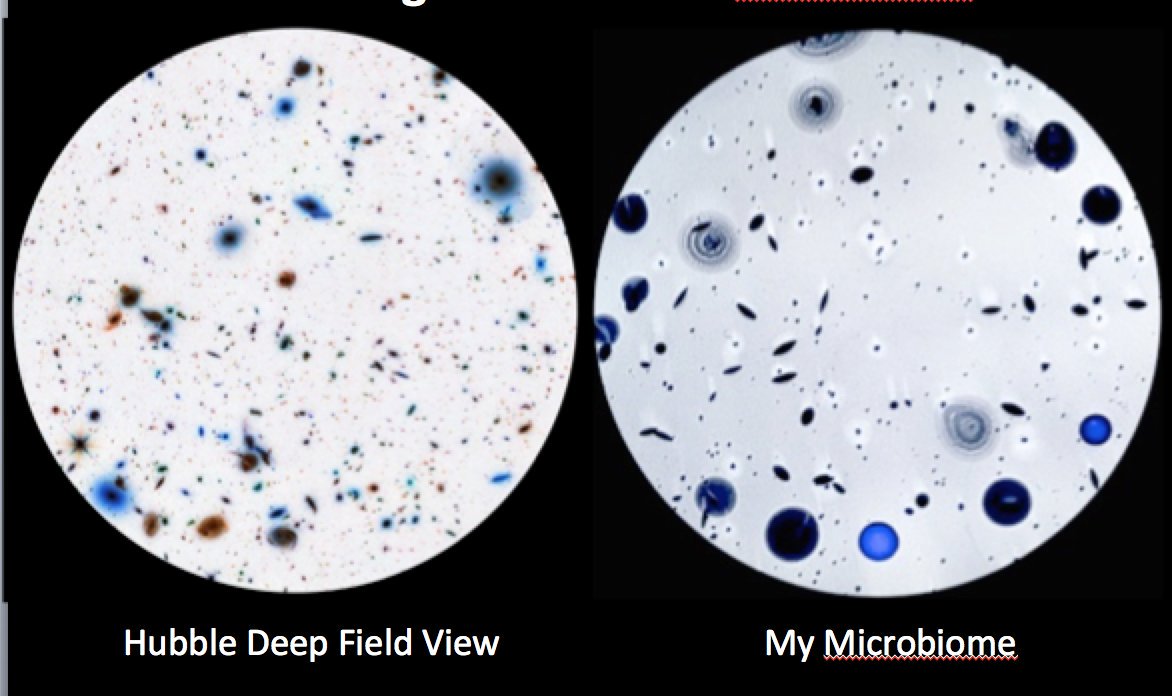

Park commented the following slide by saying that we have an internal galaxy inside our bodies. The number of stars in a galaxy can be compared to the number of cells in a colony. The images are similar but one was produced using a macroscope, the other was made with a microscope:

Simon Park, “A reflection on scale. Hubble Deep Field View of distant galaxies/my own microbiota (bacteria that live in/on me.)” Image: Simon Park

Photo on the homepage: Christine Borland, English Family China, 1998. Photo: imageobbjecttext.