Croix Gagnon and Frank Schott, Project 12:31

Semen, cell cultures, urine, feaces, tears, blood, hair, skin– the human body has been used not merely as the subject of art works, but also as their substance.

Last week, the Institute of Advanced Studies at University College London held a symposium that explored the use of “biomaterial” in modern and contemporary art practices.

Human bodily materials are frequently invested with highly symbolic cultural power and complex visceral and emotional entanglements, thus the use of human biomatter as art medium opens up an intriguing cultural space to reflect critically upon the relationships between materiality, aesthetics, affective response, ethics and the production of cultural meaning.

Bodily Matters: Human Biomatter in Art. Materials / Aesthetics / Ethics was a remarkably interesting and enlightening symposium. Almost every speaker was reading their paper which would normally make me want to pack my bag and sneak out of the room but the content of the papers was so fascinating that i stayed glued to my chair. What surprised me the most over the course of the sessions is that the art discussed was actually good. There was none of that sciart malarkey. These were works with artistic/aesthetical/critical value, rather than works which sole claim to substance is that they dally with scientific innovations.

My notebook is now full of scribblings and I’ll try and blog whatever is decipherable in the coming days. Taking it chronologically. Today, my notes will be covering the first morning. The session was called What Remains: Traces, Transitionary & Fluid Matters and revolved around a lot of blood, crimes and corpses.

Angela Strassheim, Evidence No. 2, 2009

Angela Strassheim, Evidence No. 13, 2009

Angela Strassheim, Evidence (pitchfork), 2009

Dr Elinor Cleghorn (University of Oxford, Ruskin School of Art) kicked off the day by presenting Light remains: Alchemical affect in Angela Strassheim’s ‘Evidence’.

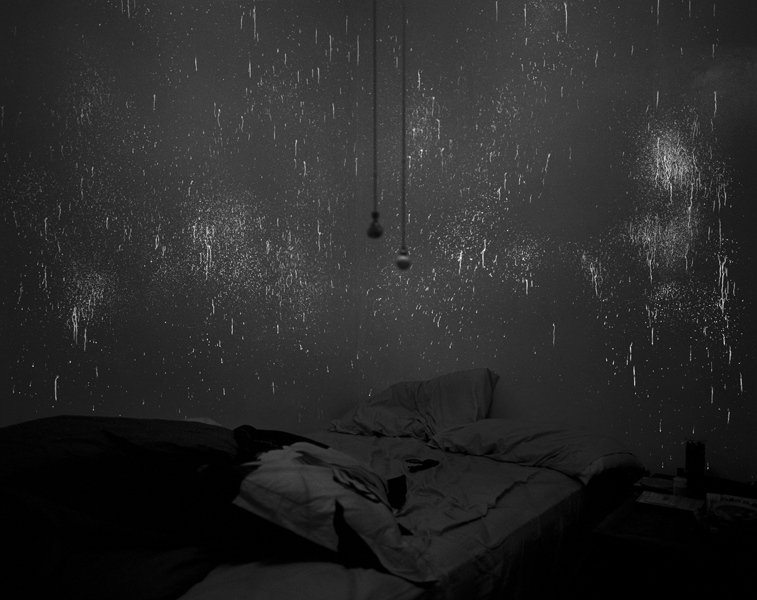

Artist Angela Strassheim used to be a forensic and biomedical photographer but later studied for an MFA in photography at Yale University. In 2008 and 2009, she visited homes where familial homicides had occurred. There was nothing left to see in the rooms where the crimes had taken place. The spaces had been scrubbed clean, some of the walls had been repainted and new families had moved into the houses.

Strassheim often found it difficult to access the spaces where the murders had taken place. She visited some 140 homes but only 18 families allowed her to take photos. Once granted permission to access the room of the murder, the artist used techniques usually reserved for police forensics to unveil the hidden residues of violent murder. The “Blue Star” solution she uses contains luminol, a chemical that reveals residual DNA protein at crime scenes, as it reacts with the iron in haemoglobin.

In order to obtain the images of the rooms, Strassheim closed doors and curtains to keep light to a minimum and then shot long exposures of between 10 minutes and an hour.

In the photos, blood that is otherwise invisible to unaided human perception appears as bright flecks and splatters. The images almost haptically reactivate the physical memory of an act of violence and revive the biomaterial traces left behind by the deceased.

None of the image is accompanied with a text that details what happened in these rooms. However, the title of the photos showing the outside of the houses lists the murder weapons used while the images of the rooms suggest a whole narrative embedded in stillness.

Angela Strassheim, Evidence No. 8, 2009

Cleghorn told us a few words about the story behind Evidence 8. This is one of the very few houses where the family had remained after the murder of a teenage girl by her step-father. The mother had cleaned the room. The luminol shows the blood spillage but it also records the bleach and thus the attempts to hide the crime.

Bust of San Gennaro, 1304-1305. Photo via Napoli x quartiere

Liquefaction of San Gennaro’s blood. Photo via Napoli fanpage

In her paper Blood Heads. From San Gennaro to Marc Quinn, Dr. Jeanette Kohl (University of California, Riverside, Department of Art History) brought side by side ‘portrait and anti-portrait’, blood relic from the Middle Ages and contemporary artworks.

Medieval reliquaries are not only containers partaking in the spiritual power of the holy body materials they hold. They also use biomaterials. Examples include the tongue of Saint Anthony displayed in a gold reliquary in Padua or the bust reliquary of Saint Fina in San Gimignano, an object covered with leather to evoke the skin of the 13th century girl.

Kohl’s talk focused on the silver bust reliquary of Saint Januarius (or San Gennaro) in Naples. The sculpture contains the head of the martyr decapitated in the 4th century AD. Two glass vials kept separately from the head contains his blood.

Three times a year, a religious ceremony brings the head in close proximity with the blood vials, while the public prays for the miraculous liquefaction of the blood. It is said that the blood ‘recognizes’ the relic and becomes liquid again. However, if the blood remains coagulated, it is seen as a bad omen for the city. The catholic church doesn’t allow scientist analysis but a couple of theories attempt to explain the ‘miracle.’

This kind of reliquary displays the presence of the immaterial divine into material objects. The biomaterials kept in reliquaries also stand for the dead person. They constitute a portrait that fills in the gap left after the disappearance of the human body.

Marc Quinn, Self 2006, 2006

Paradoxically, the pars-pro-toto of body part reliquaries implies the indivisible nature of the individual represented, an idea also reflected in Marc Quinn’s Selfs (Blood Heads) series. The frozen sculptures of Quinn’s head are made from 9 litres of the artist’s own blood. The artist makes a new version of Self every five years, each of which documents his own physical deterioration.

Quinn’s self-portraits stands against the traditions of blood and bone reliquaries as well as secular bust portraits. His portrays are brutally material, they are made of blood that is uncontained by skin or other protective layer. The portrays are made of biomaterial matter but they coexist with the person they are portraying.

Interestingly, one of Kohl’s final remarks was that Quinn’s blood heads suggest the vampirism of the art word that ‘sucks blood and life’ out of artists.

Source Data for Photography/12:31

On the 5th of August 1993, at 12.31 precisely, 38-year-old Texas murderer Joseph Paul Jernigan was executed by lethal injection. Before his death, he had agreed to donate his body for scientific research or medical use. Little did he know that his cadaver would be frozen, sectioned and photographed for the Visible Human Project, an effort to create an anatomically detailed data set of cross-sectional photographs of the human body, in order to facilitate anatomy visualization applications.

Jernigan was a tall man. His corpse was sliced into 1,871 milimeter-thick segments and photographed by scientists.

In her talk A Wisp of Sensation, A Slice of Life, Dr. Maria Hynes (Australian National University, School of Sociology) examined Project 12:31, a ‘reanimation’ by artists Croix Gagnon and Frank Schott of the corpse through the scientific images made in the early 1990s.

Croix Gagnon and Frank Schott, Project 12:31

Croix Gagnon and Frank Schott, Project 12:31

Each image was created by combining night photography and long-exposure photographs of the segments of the corpse on a laptop screen. The stop-motion animation of the sliced body was played fullscreen on a computer, which was moved around while being photographed in a dark environment. The resulting ‘light paintings’ show a contorted, translucent corpse that seems to glide through landscapes and evoke Francis Bacon’s works.

Hynes writes in her abstract: The images of the Visible Human Project and Project 1231, I suggest, provide different perspectives on what should be read, not as a moral claim, but as a fact about the nature of bodies; namely, that bodies are irreducible to brute matter, but also to representation and figuration, because they are the site of spiritual repetitions and the differential distribution of rhythms. Drawing parallels with Francis Bacon’s paintings, in which flesh is violently deformed by the forces that traverse it and escape from it, I suggest that the ‘immobile’ body of stasis, or even death, merely amplifies the incorporeal forces that make bodies the site of events. What these events might be is a problem that, thankfully, is never solvable by scientific knowledge, though I argue that experiments at the nexus of science and art might open up productive ways of envisaging their potentials.

Zane Cerpina, Body Fluids

Zane Cerpina, visual artist (PNEK, Production Network for Electronic Art) presented her performative art project Body Fluids. The work consists of a collection of jewelry objects made from frozen human bodily liquids, such as menstrual blood, semen and breast milk. The first performance in Cerpina’s series, “Woman’s Red”, saw performers wear necklaces and earrings made out of their menstrual blood frozen into diamond shapes.

The work explores how the human body breaks boundaries over the course of the day by urinating, sweating, salivating, crying, menstruating, ejaculating, etc. Our bodies are mostly made of fluids. Yet, body fluids are seen as repulsive and artists who use body fluids in their work are often called transgressive: Andres Serrano’s Semen and Blood photos, Franko B’s I Miss You performance, Kira O’Reilly‘s Wet Cup performance, etc.

“These works have a tendency to produce extreme reactions from the audience,” the artist writes in her abstract. “Yet these reactions stem more from culturally conditioned aversions more than a somaesthetic approach. In somaesthetics body fluids carry a much higher embodied value.”