A wire brush spins around randomly, threatening your open-toe sandals. A motion-activated vacuum pump sucks out the air from a gallery space: the longer viewers remain inside, the less air for them to breathe. A cobble stone is rotating on a rope. The sole purpose of that kettle is to spread red acrylic paint on your shoes. An electric fence criss-crosses the path that leads to an art gallery or the bar. Elsewhere a randomly activated tripwire awaits visitors…

Ben Woodeson, Subservient shoe brush open toed sandals thing, 2010

Ben Woodeson, Subservient shoe brush open toed sandals thing, 2010

Ben Woodeson, Health and Safety Violation number 7, “9/10 of an iceberg is hidden from view”, 2009

Ben Woodeson, Health and Safety Violation number 7, “9/10 of an iceberg is hidden from view”, 2009

There is nothing even remotely safe in Ben Woodeson‘s works. In fact, they purposely run on hazard and liability waiver forms. Sometimes they even require safety helmets. Woodeson is from the United Kingdom, a state notorious for its stringent regulation and enforcement of workplace health, safety and welfare. Almost every artists you’ll meet in the UK have their own share of H&S-related misadventures to tell.

Woodeson’s work uses everyday objects and materials to deride and confronts head-on these often absurd rules. The pieces in his Health & Safety Violation series entice visitors to be brave and come nearer as much as they repel and unnerve them. In the coming weeks, Woodeson will present new works at transmediale in Berlin and at The Florence Trust in London. The installation he will show at the TM festival is A seemingly innocent sculptural curtain bisects the foyer space obstructing the visitor’s default routes. Avoiding the work requires a conscious detour while also engaging with it requires a willingness to take risk – an “interactive” piece that does not pretend to be harmless.

Ben Woodeson, Health & Safety Violation #2 – Shocking, 2009

Ben Woodeson, Health & Safety Violation #2 – Shocking, 2009

Ben Woodeson, Basic rough as fuck spinning spring jump out of your skin hazard, 2010

Ben Woodeson, Basic rough as fuck spinning spring jump out of your skin hazard, 2010

I’ve decided not to go to Transmediale this year (first time in 8 years) but i’ll be in London to tell you about what he’ll be showing at The Florence Trust. In the meantime, a short interview will have to do….

You’ve exhibited works that involve a very high degree of risk of injury or death to visitors in several art galleries in the UK. How did you avoid the Health and Safety hassle?

Ha! I don’t really try to avoid it, it is part of my practice, I think the dialogue between the exhibiting institutions and myself forms a layer of implied meaning within the work. Most of what I do does entail some form of risk, but the Health & Safety Violation’s are a specific group of works, where that risk is overtly presented. This is through a clear and obvious physical danger or sometimes via titles that the gallery is forced to acknowledge and negotiate how the works will be presented. Let’s face it with titles like Spinning cobblestone (high speed crack your skull open bleed through your ears version) I’m not really hiding the risk, it’s right there shouting; they’re not coming to me thinking I’m going to show a nice, safe, comforting watercolour…

How many ‘no you can’t” and “yes maybe but then you’d have to change this and this” have you met with the Health and Safety Violation series? Do you compromise?

Masses! Seriously though, I’m expecting in fact I’d say I was requiring the galleries to compromise so, I’d be a real hypocrite if I wasn’t prepared to be flexible. Besides as I mentioned, the dialogue forms a layer of implied meaning within the work. As with any negotiation, there are things that you can or can’t compromise on. I’m not prepared to lessen the work by corrupting it or compromising it is such a way that alters the meaning and basic experience that the viewer has. However, within most works there is usually some room for give and take.

As artists I think we become adept at the dialogues with institutions, curators and other artists; the pragmatics about what goes where and all that sort of thing. I’m definitely not a foot stomper or a diva. Things usually come to some form of organic conclusion that fits all concerned. I’d rather pull a work from a show than compromise too far, but, the reality is that the artists, the curator and the gallery all want a show to be as good as possible, the rest is mostly details.

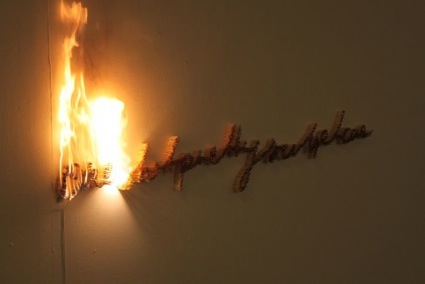

Ben Woodeson, One Shot Pretty Sculpture, 2011. Matches, fuse and random timer

Ben Woodeson, One Shot Pretty Sculpture, 2011. Matches, fuse and random timer

Do you observe visitors? Does it take long before they leave their role as a viewer and become an ‘adventurer’ of Health and Safety Violation?

Nice question! I certainly do observe, in fact I often film the openings of the shows. I need to answer in a sideways manner: Quite a lot of the recent works are different from the early Health & Safety Violations in that they have become eventful, previously the works such as Spiral Twist Hazard (featured recently on WMMNA) would randomly activate / deactivate / wait and repeat.

Ben Woodeson, Health & Safety Violation #15 – Spiral twist hazard, 2011. Image by Marcos Morilla

Ben Woodeson, Health & Safety Violation #15 – Spiral twist hazard, 2011. Image by Marcos Morilla

A lot of the newer works including ones from the new Causality series are still randomly activated but they only trigger once, their activation has become catastrophic. Examples include One Shot Pretty Sculpture where 2000 matches burn and spell out a text or Ball Droppingly Awesome Glass Sculpture where with no fanfare or warning a small mechanism drops a large steel ball into the middle of a sheet of glass. Both works are irrevocably altered by their activation; the resulting debris then forms a kind of sculptural performative afterlife. I used to hold a position that if my works were switched off they were as invalid as for example a switched off video monitor. However, these recent works are made to be experienced in several states and the exhibition(s) therefore evolves depending on the state of the works.

Ben Woodeson, Ball Droppingly Awesome Glass Sculpture, Ball bearing, glass and random timer, 2011

Ben Woodeson, Ball Droppingly Awesome Glass Sculpture, Ball bearing, glass and random timer, 2011

So, coming back to the question, the viewer is sometimes held in a kind of prolonged anticipation: What is it they are actually seeing? Quite often they’ve signed a liability waiver at the entrance, so they already have this sense of potential danger and heightened awareness, what they don’t have is knowledge of what is or is not safe… The random timing on even the repetitive works means it’s hard for them to pigeon hole works as safe, not safe etc. The works often function quite abruptly so rather than there being a sense of things about to happen, there is more a sense of things maybe about to happen but no one is quite sure. The abruptness with it’s consequent shock is definitely a fundamental factor in many of the works.

I think there is also a big difference in the adventuresome experience of those present at the opening night and those who visit in quieter circumstances. I do tweak the timings a bit so that some stuff does happen at the openings, and a lot of those people present usually know some of what I do, so in a way as a group they’ve already crossed over into the adventurer role. By contrast a visitor to a comparatively empty gallery might have little or no prior knowledge of my practice, and there might not be other viewers whose behavior could give clues.

The works are visceral and demanding, their in-your-faceness forces both experienced and inexperienced viewers to physically engage and take the adventure.

Can you tell us about your new Causality series? What is it about?

The Causality series are a new group of works started when I was preparing for my recent show at Elevator Gallery; so far they tend to be less direct. Something happens which then has a result, whereas the Violations switch on and off, there is no direct sense of cause and effect. The Causality works are no less challenging and dangerous, but somehow as I mentioned earlier, becoming more of a specific event rather than a repeating one.

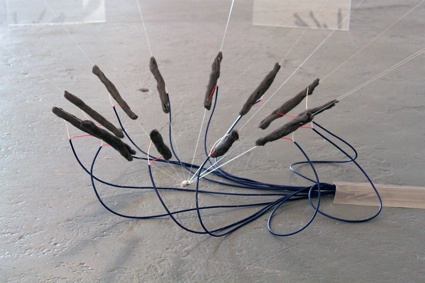

In A Perilous Environment Positively Oozing With Pain and Suffering twelve panes of glass are held angled by fishing twine, a computer randomly selects one of the twelve and ignites a wire wool fuse. The fuse burns the twine causing the glass to crash to the floor. I think the difference between the two groups of works is quite organic; they’re all confrontational, challenging and possibly a wee bit dangerous, some just seem to intuitively belong to one or the other series.

I’m definitely still working on the Health & Safety Violations for example I’m just finishing a big new piece called Health & Safety Violation #36 – Bite you on your ass and kiss your socks goodbye for Transmediale in Berlin at the end of January. I’m also concurrently working on the Causality series some of which I hope will be ready to show at the Florence Trust open weekend.

Ben Woodeson, A Perilous Environment Positively Oozing With Pain and Suffering, Glass, wire wool fuses and random timer, 2011

Ben Woodeson, A Perilous Environment Positively Oozing With Pain and Suffering, Glass, wire wool fuses and random timer, 2011

You are a Florence Trust resident this year, what are you planning to work on during this residency?

The Florence Trust residencies are really pretty special, time is whizzing by, we’re about half way through, in fact the Winter Open is the weekend of 3rd February (PV on the Friday night). For me it has been an interesting time in that I had planned to develop new works that while still clearly fitting within my interests would maybe be more versatile and flexible. However ironically 90% of the new works I’ve made have been just as difficult and confrontational as ever and so far I don’t see any signs of that shifting. I work quite intuitively; balancing concept, material and activity, and maybe it’s the church or whatever, but versatile and flexible suddenly seems far less interesting and engaging when compared to fear, fire, gravity, electricity, breaking glass and general sculptural carnage; in other words all the usual stuff that floats my boat.

Thanks Ben!

Previously: Experimental Station – Part 1, In the Laboratory.