Previous stories about AUTO. SUEÑO Y MATERIA : Cars and landscapes, Artificial traffic jam in the mountains and Manufacturing cars.

Erwin Wurm, Fat Car

Erwin Wurm, Fat Car

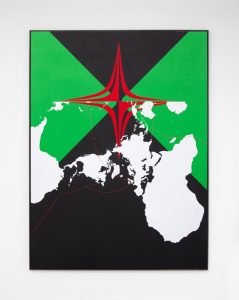

Leonardo Da Vinci was credited with sketching the world’s first self-propelled vehicle back in 1478. But da Vinci was a Renaissance Man, a man at ease in front of a religious scene to paint as much as in front of a technological challenge. There’s no artist from the Renaissance in the AUTO. SUEÑO Y MATERIA exhibition, the majority of the works exhibited come from the last two decades but they demonstrate that contemporary artists do not need to graduate as engineers to re-invent the car… even if the result of their experimentation has no ambition to compete with what comes out of a Porsche factory.

Exhibition view (photo Enrique G. Cardenas)

Exhibition view (photo Enrique G. Cardenas)

Very few of the artists participating to the exhibition are as pragmatic as Pedro Reyes. Reyes is from Mexico City, a place where car use has doubled over the past few years. There are currently over 7.9 million cars on the roads of Mexico City and around 400 000 cars added to that total every year. Traffic is beyond control. Although the government is trying to curb air pollution through public transport improvements and new laws to control emissions of new cars (source wikipedia), carbon dioxide emissions create a smog layer that severely affects the air quality of the entire Mexico Valley, damaging the health and quality of life of all its inhabitants.

Reyes’ Bicitaxi aims to provide an answer to the problem. If mass-produced the Bicitaxi could be spread all over the city center and provide transport services for short distances. The benefits of this “human-propelled vehicle” would be many, including creating an alternative for self- employment. There’s quite a few European cities which have tried to offer bicytaxi services at some point but they were so ugly most people wouldn’t want to be caught dead in one of those. Reyes’ version, on the other hand, has an almost futruristic and toy-like appeal.

Pedro Reyes, Bicitaxi: prototipo para un vehículo de pasajeros a propulsión humana, 2007

Pedro Reyes, Bicitaxi: prototipo para un vehículo de pasajeros a propulsión humana, 2007

Sometimes compared to da Vinci, Panamarenko is best known for the whimsical blimps, saucers, backpack helicopters and other flying (but mostly non-flying) machines that he spent decades building and experimenting with. The were modeled on natural elements, such as bird’s wing or the motions of insects in midair. He has now retired from the art world and started selling his own brand of coffee instead.

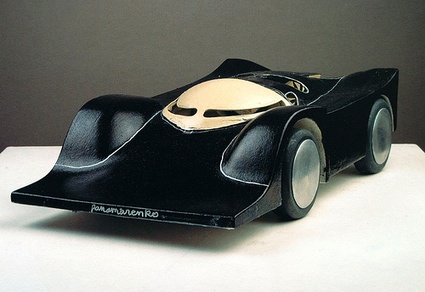

Panamarenko, Polistes (black & white), 1990

Panamarenko, Polistes (black & white), 1990

Panamarenko’s first design for a flying car dates from 1972. One of the prototypes on show at LABoral is not a flying car but a very appealing and simple rubber car. Polistes (1975) is propelled by two turbines that, when turned the other way, make brakes superfluous. Since the propulsion is direct, i.e. not via the wheels, gear changes are not necessary either (via).

Panamarenko doesn’t really care if his machines flew or not. As Alberto Martín, the curator of the exhibition, wrote: His works embody the technological dream confronted by its very own nature, its free evolution and right to failure, beyond the feasibility or performance studies proper to industry. He seems to be reminding us that the future has always been located on the shore of dreams and ideals.

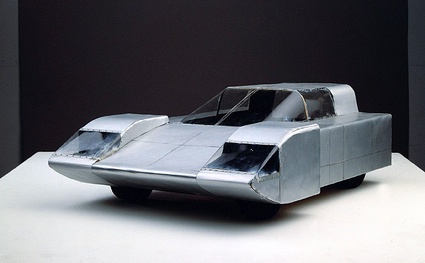

Model of Prova-car from ’67, 1967

Model of Prova-car from ’67, 1967

Erwin Wurm‘s UFO doesn’t fly either. Neither does it have any functional ambition. UFO is the epitomy of fanciness and futuristic dream. It is shiny and evokes the flying cars that no engineer has ever managed to pull out of their sci-fi setting.

Erwin Wurm, UFO, 2006

Erwin Wurm, UFO, 2006

At the other hand of the spectrum is Xavier Veilhan‘s Vehicle. That one as minimal as it can get: chassis several pipes, holding a small jet engine and sustained by four bicycle wheels. The vehicle works perfectly but is absolutely useless, its a schematic reduction of the automobile, a prototype with no other quality than its own essential nature. The “primitivism” and extreme reduction of the car is at odds with the sophistication generally associated with car design and technology. Is a vehicle reduced to its most basic functions still be regarded as a vehicle? How far can its reduction go till we don’t recognize its essence anymore?

Xavier Veilhan, Le Véhicule, 1995

Xavier Veilhan, Le Véhicule, 1995

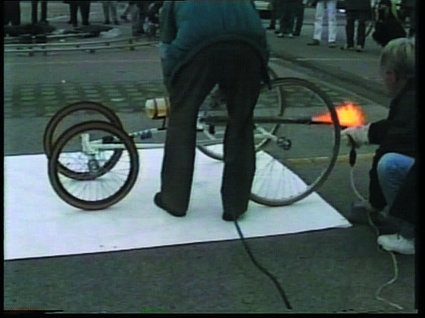

Roman Signer followed the same path of reduction and minimalism with Wagen: four wheels a fan generating energy to produces motion. Here again, spectators are questioned about the true nature of the vehicle they have in front of their eyes: Is it still a vehicle? Is it drivable? What is it for? Wagen brings to the surface the mechanisms implicit in our relationship with the goods around us.

Roman Signer, Wagen, 1998

Roman Signer, Wagen, 1998

I’ll close this post with one of my favourite works in the show, the sublimely absurd Pull by Michele Bazzana. Once again a minimal vehicle but this one it is powered by two drills that probably consume much more energy than would normally be required to move such a basic vehicle.

Michele Bazzana, Pull, 2006

Michele Bazzana, Pull, 2006

Related post: Panamarenko retrospective.

Auto. Sueño y materia, curated by Alberto Martín, runs until September 21 at Laboral Centro de Arte y Creación Industrial.