Last week, I was in Liverpool for some overdue FACT action and Art Turning Left: How Values Changed Making 1789-2013 which examine how the production and reception of art has been influenced by left-wing values, from the French Revolution to the present day.

The main preoccupation of the exhibition is thus not the militant commentaries behind artworks but the effect that political values and social movements have had on the production modes, aesthetics and communication of visual culture. As such Art Turning Left stands out from other shows dedicated to political art or activism.

The left-wing values considered in the exhibition include the empowerment of the working classes, the equality of the sexes, the search for alternative economies, etc. These values seeped into art world where they translated into the rejection of the concepts of fine art and of the individual expression in favour of an art made by or with the help of the community, the adoption of new media, a greater mingling between art and life (through crafts, design and in particular graphic design),

Art Turning Left, installation view with Chto Delat, Study, Study and Act Again. © Tate Photography

Art Turning Left, installation view with Chto Delat, Study, Study and Act Again. © Tate Photography

Zvono Group, Art and Soccer 1986. © ZVONO

Zvono Group, Art and Soccer 1986. © ZVONO

Art Turning Left, installation view with Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat to the left. © Tate Photography

Art Turning Left, installation view with Jacques-Louis David’s The Death of Marat to the left. © Tate Photography

Art Turning Left is a great show under many aspects and i’ve certainly felt enthusiastic about discovering new politically-engaged artworks that stood up the time. But it has its flaws. On the one hand, i enjoyed the fact that the show is distributed according to questions (“Do we need to know who makes art?” “Can art affect everybody?” “Does participation deliver equality?”, etc.) rather than chronology and it certainly is refreshing to find a respectable painting by David between an installation by Goldin+Senneby and a wall of revolutionary posters. On the other hand, being constantly pinballed from one historical period to another and from one geographic locations to an entirely different one gets a bit confusing.

if the show acknowledges that artistic practice in the 20th and 21st century has been ‘democratized’ as its some of its means of production and distribution have become accessible to all (thanks to photography, printing, digital, etc.), i don’t think i’ve seen any reference to some of the most stimulating features of 21st century culture: free software, free culture, 3D printing, etc. Thinking of it, there’s very little reference to what computers/ the internet have done to advance new ideas and practices.

Jacques Louis David and Studio, The Death of Marat, 1793

Jacques Louis David and Studio, The Death of Marat, 1793

It did start with the best intentions though. One of the highlights of the exhibition is The Death of Marat, by Jaques-Louis David. Both David and Jean-Paul Marat were members of the Jacobian Republican group during the French Revolution. After the assassination of the revolutionary journalist, David had several copies of The Death of Marat produced on various supports in order to relay the political message to the masses. Instead of being displayed at the elitist salon like his other works, David sent them across France for everyone to see.

Art Turning Left is a show i’d recommend to everyone for the quality of the works exhibited, for the ideas (left-wing or not) which unfortunately are in serious need of our attention these days but for all its undeniable qualities, the exhibition remains more academic than its topic deserved.

Also this definitely isn’t a show for someone with a ‘working class’ budget: entrance fee is £8.

Now about the artwork i discovered or rediscovered in the show?

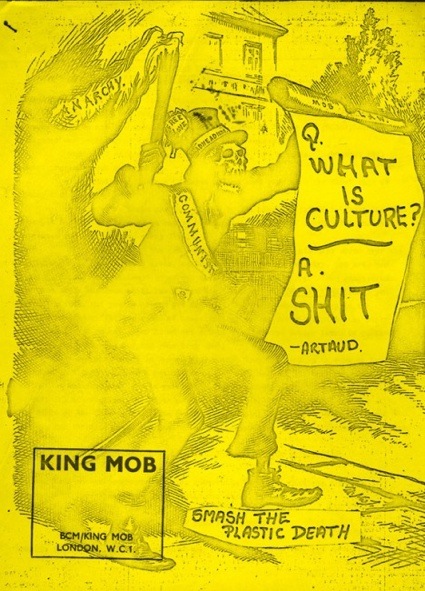

Front cover of a King Mob anti-culture publication. Courtesy Tate Archive © Tate. Photo: Rod Tidnam

Front cover of a King Mob anti-culture publication. Courtesy Tate Archive © Tate. Photo: Rod Tidnam

King Mob! The London-based group called themselves ‘gangsters of the new freedom’ and adopted a confrontational approach to underline the cultural anarchy and disorder being ignored in 1960s-1970s Britain. I read in the gallery that one day, they took over the Christmas Grotto in Selfridges and gave out all the presents to the kids for free. The department stores had then to literally take the presents back from the children’s arms before they left. I burst hysterically into laughter when i read that.

Who are today’s King Mob?

Goldin+Senneby, Money Will Be Like Dross. Installation view: The Magic of the State, Lisson Gallery, London

Goldin+Senneby, Money Will Be Like Dross. Installation view: The Magic of the State, Lisson Gallery, London

In the 1780s mineralogist August Nordenskiöld was employed by the Swedish king Gustav III to discover the legendary alchemical substance Philosopher’s Stone and turn base metal into gold. The gold was intended to finance Sweden’s military and economic expansion, but Nordenskiöld had a different agenda, he aimed to produce so much gold that its value would be lost and the “tyranny of money” abolished. One of the few remaining artifacts from Nordenskiöld’s laboratory is a coal burning alchemy furnace. Goldin+Senneby offer to supply collectors with necessary components and instructions for the reconstruction of a replica of Nordenskiöld’s furnace. The manual is produced in a numbered but unlimited edition, and as each edition is sold the price goes up, making the item more expensive the less unique it is.

Grupa Zvono, Akcija “Mondrian”, 1986 (Sarajevo)

The best discovery in the show for me was Grupa Zvono. Founded in 1982, the group organized performances that aimed to present an art that was different from the then dominant forms outside of galleries and closer to ‘the man on the street.’ Or, in one case, in the football stadium.

Cildo Miereles, Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project 1970. © Cildo Meireles. Image courtesy Tate

Cildo Miereles, Insertions into Ideological Circuits: Coca-Cola Project 1970. © Cildo Meireles. Image courtesy Tate

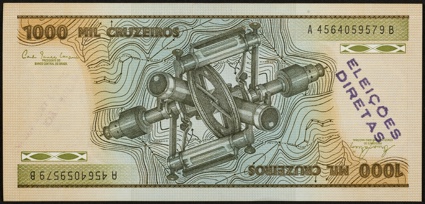

Cildo Meireles, Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project 1970. © Cildo Meireles. Image courtesy Tate

Cildo Meireles, Insertions into Ideological Circuits 2: Banknote Project 1970. © Cildo Meireles. Image courtesy Tate

Cildo Meireles took Coca-Cola bottles and modified them. When empty they look ordinary, but political statements printed on the glass in white are revealed as the bottles are filled with the brown liquid. They range from ‘Yankees Go Home’ to instructions on how to make a Molotov cocktail. The empty bottles with the messages were then recycled back into the Coca-Cola distribution system.

The artist also stamped political commentary onto banknotes, the most frequent was ‘Quem Matou Herzog?’ (‘Who Killed Herzog?) in reference to a journalist who had died in police custody under suspicious circumstances.

Brazil was then under an oppressive military dictatorship and the Insertions constituted a form of guerrilla tactics of political resistance that eluded strict state censorship.

Meireles said that he sought to use systems of communication and distribution that were not centrally controlled, like the media or press, and that: The Insertions would only exist to the extent that they ceased to be the work of just one person. The work only exists to the extent that other people participate in it. What also arises is the need for anonymity. By extension, the question of anonymity involves the question of ownership. When the object of art becomes a practice, it becomes something over which you can have no control or ownership.

Ruth Ewan, A Jukebox of People Trying to Change the World (Ongoing archive since 2003). Installation view Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe 2012. Photo: Stephan Baumann, bild_raum

Ruth Ewan, A Jukebox of People Trying to Change the World (Ongoing archive since 2003). Installation view Badischer Kunstverein, Karlsruhe 2012. Photo: Stephan Baumann, bild_raum

Ruth Ewan compiled hundreds of protest songs in A Jukebox of People Trying to Change the World. All of which, visitors are invited to play in the gallery.

Atelier Populaire, Untitled (Début d’une lutte prolongée) 1968 © Archivio Sessantotto – Antonio Ricci, Italy

Atelier Populaire, Untitled (Début d’une lutte prolongée) 1968 © Archivio Sessantotto – Antonio Ricci, Italy

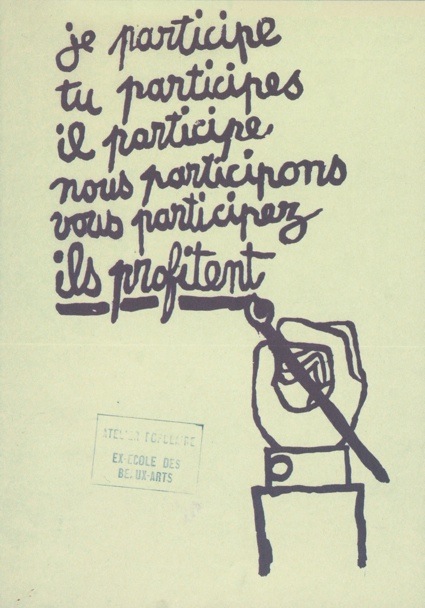

Atelier Populaire, Je Participe 1968. © Archivio Sessantotto – Antonio Ricci, Italy

Atelier Populaire, Je Participe 1968. © Archivio Sessantotto – Antonio Ricci, Italy

Atelier Populaire’s posters broadcast the demands and protests of the student/intelligentsia/trade-union of a May 68 Paris charging the French Establishment.

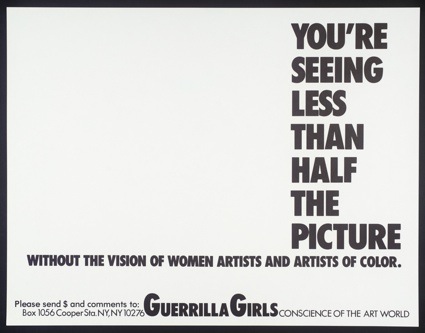

![0Guerrilla Girls - [no title] 1985-90.jpg](https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wow/0Guerrilla%20Girls%20-%20%5Bno%20title%5D%201985-90.jpg) Guerrilla Girls, [no title] 1985-90. © courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com. Image courtesy Tate

Guerrilla Girls, [no title] 1985-90. © courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com. Image courtesy Tate

Guerrilla Girls, [no title] 1985-90. © courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com. Image courtesy Tate

Guerrilla Girls, [no title] 1985-90. © courtesy www.guerrillagirls.com. Image courtesy Tate

Guerilla Girls anonymously produced propaganda posters that were (are!) boldly drawing attention to the absence of women artists in major art exhibitions.

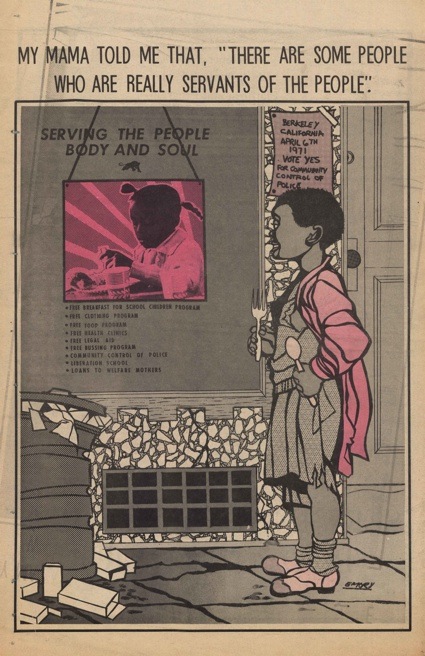

Emory Douglas, Supplement to The Black Panther, 10-04-1971 1971. © DACS, London 2013. Photo: IISG BG D18/246, International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam)

Emory Douglas, Supplement to The Black Panther, 10-04-1971 1971. © DACS, London 2013. Photo: IISG BG D18/246, International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam)

Emory Douglas worked as the Minister of Culture for the Black Panther Party from 1967 until the Party disbanded in the 1980s. His graphic art illustrated the struggles of the Party in most issues of the newspaper The Black Panther.

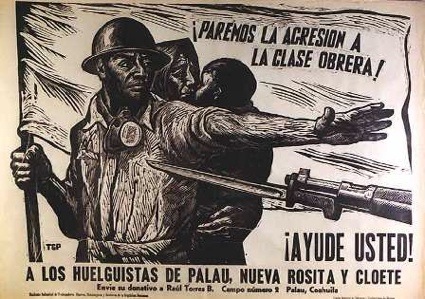

Leopoldo Méndez, Paremos la agresión a la clase obrera

Leopoldo Méndez, Paremos la agresión a la clase obrera

Taller de Grafica Popular (“People’s Graphic Workshop” or TGP) was an artist print collective founded in Mexico in 1937. They used posters and flyers as platforms to promote revolutionary social causes.

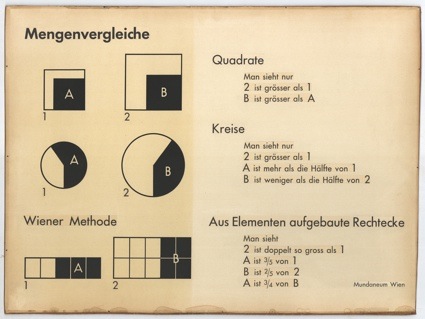

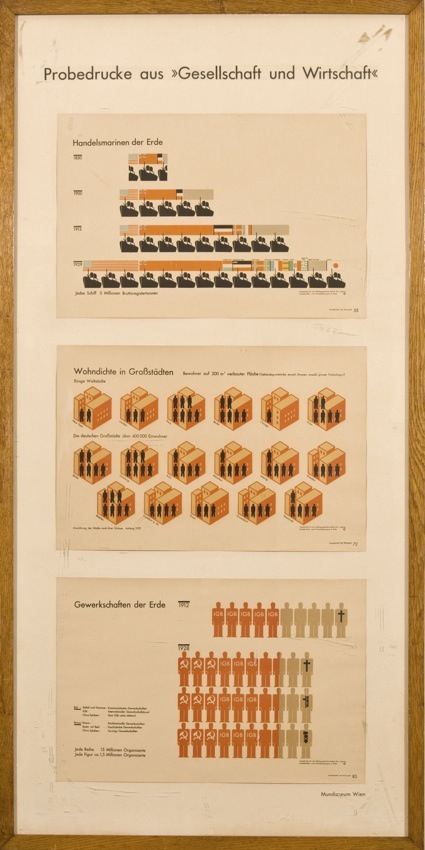

Gerd Arntz, Mengenvergleiche ; Signaturen der Bildstatistik nach Wiener Methode 1925-1949. © DACS, London 2013. NEHA BG S4/11-B International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam)

Gerd Arntz, Mengenvergleiche ; Signaturen der Bildstatistik nach Wiener Methode 1925-1949. © DACS, London 2013. NEHA BG S4/11-B International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam)

Gerd Arntz, Probedrucke aus “Gesellschaft und Wirtschaft” 1925-1949. © DACS, London 2013. NEHA BG S3/52-A, International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam).

Gerd Arntz, Probedrucke aus “Gesellschaft und Wirtschaft” 1925-1949. © DACS, London 2013. NEHA BG S3/52-A, International Institute of Social History (Amsterdam).

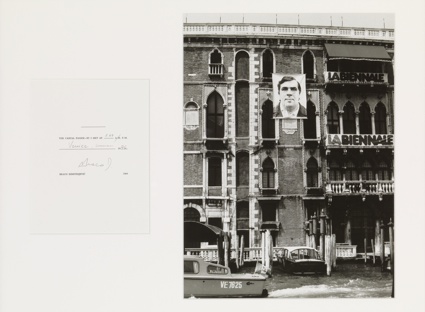

Braco Dimitrijevic, Casual Passer-by I met at 1.43 PM, Venice 1976, 1976. © Braco Dimitrijevic. Image courtesy Tate

Braco Dimitrijevic, Casual Passer-by I met at 1.43 PM, Venice 1976, 1976. © Braco Dimitrijevic. Image courtesy Tate

Art Turning Left, installation view, with the Banner for The Worker’s Union – Holloway branch – Solidarity of Labour, after Walter Crane dated c. 1898 and Braco Dimitrijevic, Casual Passer-by I met at 1.43 PM, Venice 1976 © Tate Photography

Art Turning Left, installation view, with the Banner for The Worker’s Union – Holloway branch – Solidarity of Labour, after Walter Crane dated c. 1898 and Braco Dimitrijevic, Casual Passer-by I met at 1.43 PM, Venice 1976 © Tate Photography

Art Turning Left: How Values Changed Making 1789-2013 was curated by Francesco Manacorda and Lynn Wray, is on view until 2 February 2014 at Tate Liverpool.