On a sunny afternoon in Florence i visited one of those exhibitions which lingers in your mind for days because of the questions and debates they set in motion inside your brain. The theme of the Art, Price and Value was selected a long time ago but given the current frenzy about the state of the art market it could not have been more timely nor thought-provoking. The exhibition, which closed a few days ago at the Strozzina cultural Center, explored how the economy has come to manipulate art production, affecting its every aspects.

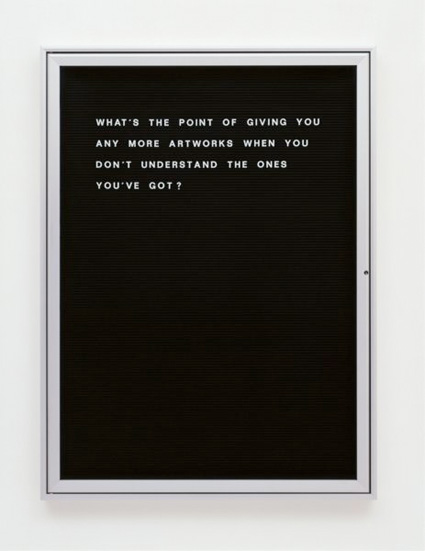

Bethan Huws, Untitled, 2006, alluminio, vetro, lettere in gomma e plastica, courtesy the artist

Bethan Huws, Untitled, 2006, alluminio, vetro, lettere in gomma e plastica, courtesy the artist

Contemporary art plays an increasingly prominent role in our culture, with some of its most visible figures reaching a status that can only be compared to the one of fashion designers, Hollywood actors and pop stars. Many people have come to associate contemporary art with tactics made of shock, awe and circus. The economic power of art is reflected in the spectacular prices obtained at international auctions, the increasing number of museums accused of ‘blockbusteritis‘, biennials becoming as necessary to the tiniest country as a local airport, festivals popping up everywhere (just how many media art festivals are there in The Netherlands exactly?), star-stud openings and mega-happenings.

The exhibition at the CCCS features the work of contemporary artists which throws light on the mechanisms of the international art system. The selection explores different points of view, ranging from complete conformity to the prevailing rules of the market, to irony and sarcasm and even to an “anti-market” stance, taken by those anxious to avoid the commercial aspects of the art market entirely.

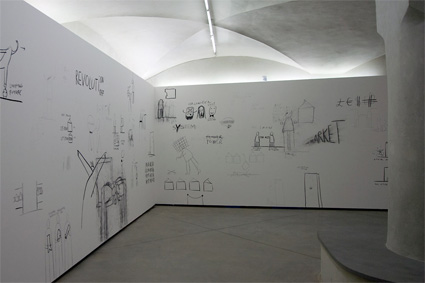

Dan Perjovschi

Dan Perjovschi

Dan Perjovschi whose work i’ve seen in almost every single European city i visited last year was invited to cover the walls on one of the exhibition rooms with some of his ‘site-specific and time-specific’ comic strip style drawings. Incisive and spot-on, the drawings sharply sum up current political, ethical or cultural issues. For the CCCS exhibition, the artist’s charcoal sketches comment on the paradoxes and absurdities of the contemporary art system.

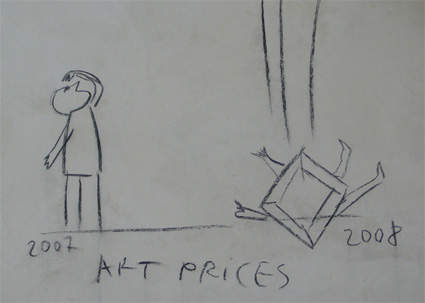

Dan Perjovschi, 2008. Image CCCS

Dan Perjovschi, 2008. Image CCCS

Dan Perjovschi, 2008

Dan Perjovschi, 2008

When engaging with the issue of art and money, it is impossible to ignore the two most successful money-milkers of the moment: Takashi Murakami and Damien Hirst. I’ll pass briefly over these two as i doubt they need much introduction.

Takashi Murakami, Sphere Monogram (Black), 2003

Takashi Murakami, Sphere Monogram (Black), 2003

Just like he did notoriously and controversially a few months ago at the Brooklyn Museum, Murakami exhibited the bags he designed for Louis Vuitton in the gallery (though there was no shop to sell the accessories this time.) Further blurring the frontiers one could make between fine art and commercial goods, he had a black canvas covered with the multicoloured letters L and V and other symbols associated with the famous monogram.

A Lovely Day, 1997-1998. Courtesy private collection. photo © Damien Hirst. All rights reserved. DACS 2008

A Lovely Day, 1997-1998. Courtesy private collection. photo © Damien Hirst. All rights reserved. DACS 2008

No one better than Damien Hirst has managed to reduce to tiniest bits of dust the romantic myth of the ‘artiste maudit’. While art experts were claiming that the party was over and that the art market would soon feel the effects of the global financial turmoil, Hirst was merrily enjoying a two-day auction at Sotheby’s where his works smashed top estimates and reached a total of $198 million. Some critiques are nevertheless predicting that the Hirst hype might soon deflate.

The Florence exhibition had two of his most iconic pieces: the first one is part of a long series of canvases and other objects featuring butterflies -metaphor for mortality, a theme that Hirst has explored widely- mounted on a glossy surface and manufactured by Hirst’ team of assistants. This type of art production can be traced back to the workshops of Renaissance artists such as Sandro Botticelli and to the factory of Andy Warhol with whom the British artist shares an acute understanding of the market mechanisms.

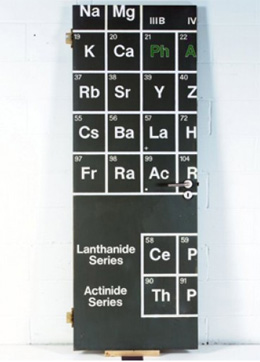

Grey Periodic Table Door, 1997-1998 from The Pharmacy restaurant, London © Damien Hirst & Other Criteria

Grey Periodic Table Door, 1997-1998 from The Pharmacy restaurant, London © Damien Hirst & Other Criteria

The second piece on show was a door which had been part of the entrance of the restaurant The Pharmacy which Damien Hirst co-owned in the late 1990s in London. When the place closed in 2003, its interior -from a sculpture of Hirst’s own DNA helix to rolls of wallpaper- was sold at auction at Sotheby’s. Every single object was sold for a multiple sum of the estimated auction price. Many of these items were not unique works of art, but industrially produced goods. The fact the they had been part of a project associated with the brand name of Damien Hirst turned these objects into highly coveted artefacts.

Hirst is one of The Young British Artists (YBAs). So is Michael Landy. Yet, they have adopted strikingly opposite strategies when it comes to money and art.

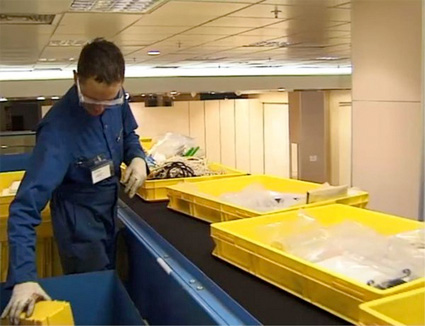

Back in 2001, Landy stunned the mainstream press with his performance/installation Break Down. The artist, dressed in blue boiler suit, systematically cataloged and pulverized all his belongings including his birth certificate, all his books and works of art, his car and driving license. Not even the most cherished souvenirs, from a childhood teddy bear to a sheepskin coat that belonged to his father, could escape the grinder.

Michael Landy, Break Down, 2002, still from video documentary, 16.36 min

Michael Landy, Break Down, 2002, still from video documentary, 16.36 min

The video on show at CCCS documents the operation: in a vacant shop space located on the always shopping-busy Oxford Street in London every single item is placed on a conveyor belt and transported to its final destruction in a grinder.

Michael Landy, Breakdown. Photo credit – Hugo Glendinning © Commissioned and produced by Artangel, 2001

Michael Landy, Breakdown. Photo credit – Hugo Glendinning © Commissioned and produced by Artangel, 2001

The performance didn’t even have any commercial value: Landy refused to have the bags of rubbish left from the process sold or exhibited in any form. He made no money as a direct result of Break Down, and following it had no possessions at all. A BBC documentary followed the artist as he had to rebuild his material life.

Breakdown. Photo credit – James Lingwood © Commissioned and produced by Artangel, 2001

Breakdown. Photo credit – James Lingwood © Commissioned and produced by Artangel, 2001

The works puts a distressing human element onto the much-criticized but eagerly embraced consumer society. Should the objects ones owns be the sole factor that determine who an individual is? What happens to one’s identity when all theses objects have been annihilated?

Image on the homepage: Denis DARZACQ, Hyper n° 8, 2007, serie di 4 fotografie, courtesy the artist; VU’La Galerie, Paris.

To be continued…

Previously at CCCS-Strozzina: Emotional Systems, at the Strozzina in Florence, China China China China !!! Chinese contemporary art beyond the global market, Exploded Views – Remapping Firenze.