Facade of the Open Eye Gallery. Paul Morrison, Urformen © Photo Paul Karalius

Facade of the Open Eye Gallery. Paul Morrison, Urformen © Photo Paul Karalius

Last month, i visited the Liverpool Biennial. It was boring (BO-RING) but it was still worth the trip. One: because I love Liverpool and i’m happy as long as people around me have that cute accent. Two: because of the show at the Open Eye Gallery. It is part of the official programme of the biennial but it was one of the few shows in town that made me think and reflect upon the art world and the way it is represented/represent itself.

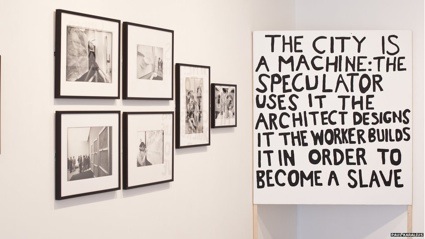

Not All Documents Are Records: Photographing Exhibitions as an Art Form looks at photographic works that bring a critical and artistic gaze on some of the most important art events in the world and asks the question: “Can photography be the site where the history of an exhibition is produced and still retain its independent artistic autonomy, thus overcoming pure documentation?”

Four bodies of works are brought together to make us reflect on this question. Two are contemporary, they are by Cristina De Middel of the Afronauts fame and by Ira Lombardia. The other two, by Ugo Mulas and Hans Haacke respectively, are historical.

Venice, 1968. Workers protests, XXXIV Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs

Venice, 1968. Workers protests, XXXIV Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs

Venice, 1968. Student protests, XXXIV Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs

Venice, 1968. Student protests, XXXIV Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs

Photo © Paul Karalius

Photo © Paul Karalius

Photo © Paul Karalius

Photo © Paul Karalius

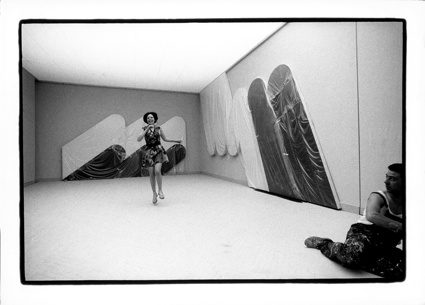

Venice, 1968. Room of Rodolfo Aricò, XXXIV Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte. Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs

Venice, 1968. Room of Rodolfo Aricò, XXXIV Esposizione Biennale Internazionale d’Arte. Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs

I’m going to start with Ugo Mulas‘ take on the Venice biennale of 1968. I knew the photographer’s work for his portraits of the superstars of the art world in the 1960s. But the photos exhibited at the Open Eye Gallery are miles away from the glamour you might expect from the Venice event.

Mulas had been covering each edition of the Venice biennial since 1954. The images in the gallery date from 1968, a year marked by social uprisings around the world (Mai 68 in France, anti-Vietnam war demos, etc.) The art biennial, which naturally echoes changes in society, experienced similar turmoils. Students and intellectuals took to the street to protest against the establishment represented by the Venice Biennale, brandishing banners that denounced the “policed biennial of the bourgeoisie” (policemen were indeed guarding the entrance of the Giardini) and claiming that ‘La Biennale è fascista.’

They also questioned the institution itself on matters such as freedom of speech and vilified it for its sales department, accusing the biennial of being a capitalist playground for the rich. The biennale’s board subsequently dismantled the sales office.

In solidarity, some of the participating artists covered up their works, withdrew their work, turned them over or wrote over “in these conditions i’m not working.”

Mulas photographed the most salient moments of the opening: the protests, the curators carelessly drinking spritz on Piazza San Marco, the police crackdown against demonstrators, etc.

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Gonzales Nun, 1959 © Hans Haacke © DACS, London

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Gonzales Nun, 1959 © Hans Haacke © DACS, London

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Kandinsky, Micky Mouse, 1959 © Hans

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Kandinsky, Micky Mouse, 1959 © Hans

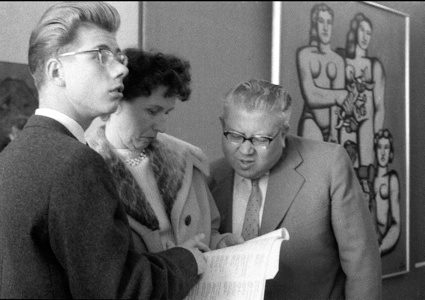

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Léger Family, 1959 © Hans Haacke © DACS, London

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Léger Family, 1959 © Hans Haacke © DACS, London

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Cleaning Women, 1959 © Hans Haacke © DACS, London

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Cleaning Women, 1959 © Hans Haacke © DACS, London

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Magritte 2 Profiles, 1959 © Hans Haacke © DACS, London

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Magritte 2 Profiles, 1959 © Hans Haacke © DACS, London

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Pollocks, Large Group, 1959 © Hans Haacke © DACS, London

Photographic Notes, documenta 2, Pollocks, Large Group, 1959 © Hans Haacke © DACS, London

The context of Hans Haacke‘s photos of the second edition of Documenta in Kassel is very different from the one of the 1968 biennial. Founded in 1895, the Venice biennial is the oldest exhibition of its kind. Documenta was created 60 years later as a means for bringing Germany up to speed with the most modern and contemporary art forms that had been banned under Nazi’s politics of artistic obscurantism and censorship.

Haacke, still a student at the Art Academy in Kassel in 1959, worked as an exhibition guard for the second edition of Documenta. In his free time, he independently took on the task of visually ‘documenting Documenta’. The 26 black and white images hanging on the walls of the Open Eye Gallery are witty and full of humour. Instead of being strictly about the art exhibited, the images display Haacke’s interest into the rituals and peculiarities of an art event. They show how absurd the dialogue between artworks and viewers can be. A family attempts to find some relationship between a description in the catalogue and the work hanging on the wall. A young boy is far more interested in mickey magazine than in the Kandinski hanging behind his back. Other photos gives us a glimpse of what happens behind the curtains of the art world: cleaning ladies doing their job, a Moore sculpture waiting next to a pile of bricks to be carried to the exhibition room.

Nowadays, most of us have seen images of the kind. The museum photos of Thomas Struth or Martin Parr’s sneaky portraits of collectors at Dubai Art Fair, for example. In 1959, photographers’ sociological explorations of the art world were pretty unusual.

Cristina De Middel. Photo © Paul Karalius

Cristina De Middel. Photo © Paul Karalius

Cristina De Middel

Cristina De Middel

Cristina De Middel

Cristina De Middel

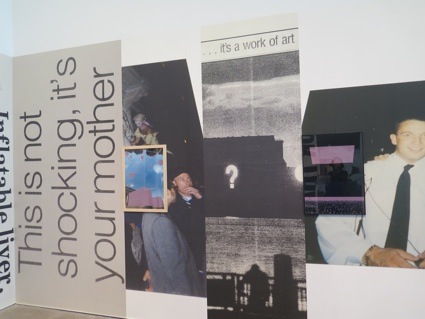

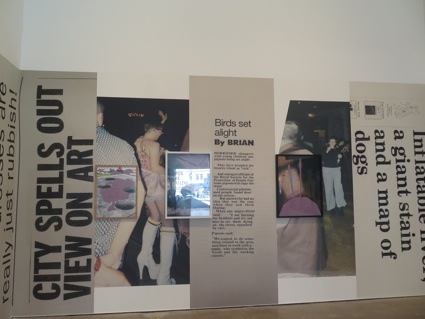

Cristina De Middel was invited by the gallery to imagine what the future edition of the Liverpool Biennial would be like. The commission came as the preparations for the event were underway.

Instead of going into wild speculations, the photographers looked for evidence in the archives of photography and press cuttings that documented past editions of the event. She then used and remixed the images and headlines in prints that cover the walls of the first room of the gallery.

To create her collage, she contacted both the photographers who had made the original images and the artists whose work appear in the photo. The photographers gave her the permission to use and rework their images. Many of the artists, to my great surprise, refused. So while artists have been constantly borrowing and re-appropriating other artists works to create new ones, they negate photographers the possibility to do so. Does that mean that a photographer is not an artist? That they can only produce images that document? To meet their censorship, De Middel painted over the artworks appearing in the photos, blurring and often even distorting their contour. Her new body of work interrogates thus the authenticity of photography (something she had done previously with the Afronauts, a series that charted the 1964 Zambian space programme which never actually came to its full realization) and highlights the tension between creativity and documentation that the photographic medium encompasses.

Ira Lombardia, And I Think to my selffffffffff what a wonderful worlllllllllld, 2012. Photo by Paul Karalius

Ira Lombardia, And I Think to my selffffffffff what a wonderful worlllllllllld, 2012. Photo by Paul Karalius

And I Think to my selffffffffff what a wonderful worlllllllllld © Ira Lombardia, 2012

And I Think to my selffffffffff what a wonderful worlllllllllld © Ira Lombardia, 2012

And I Think to my selffffffffff what a wonderful worlllllllllld © Ira Lombardia, 2012

And I Think to my selffffffffff what a wonderful worlllllllllld © Ira Lombardia, 2012

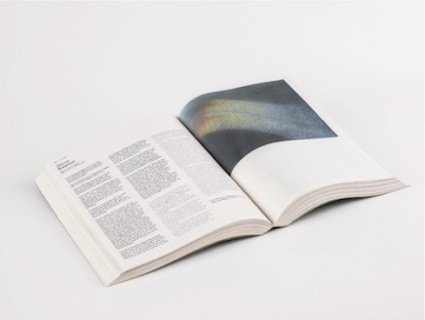

Upstairs, i almost missed the work of Ira Lombardía. During her visit of the last edition of Documenta, the artist saw a light phenomenon on the floor of one of the exhibition gallery. She mistook it for an authentic work of art (such confusions happen to the best of us when dealing with contemporary art.) Lombardía took a photo of it and went on to create a whole narrative around it. She invented an artist and a description for the artwork that never was. She then copied faithfully the catalogue of the Documenta exhibition and substituted one of the artworks by her photo of the light phenomenon and added the bio of her fictitious artist. She later wrote a letter of apology to the artist whose name and work she had removed from the catalogue.

Not All Documents Are Records: Photographing Exhibitions as an Art Form, curated by Lorenzo Fusi, remains open until 19 October 2014 at the Open Eye Gallery in Liverpool.