A visit of the exhibition Mind Maps: Stories from Psychology yesterday made me realize, once again, that i should be grateful to live here and now and not at a time when melancholia was treated with a ‘healthy’ dose of electric shocks and nerves were supplied with a ‘vital energy’ by wearing an electrical belt previously soaked in vinegar. This ancient cure looked like jolly good fun though.

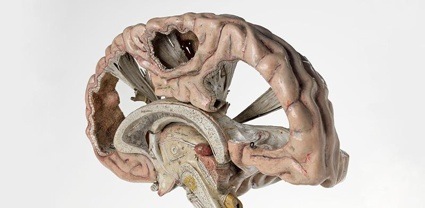

Model of a human brain, sectioned, French, first half 19th century. Image courtesy Science Museum

Model of a human brain, sectioned, French, first half 19th century. Image courtesy Science Museum

Susan Aldworth, Transition series, 2010

Susan Aldworth, Transition series, 2010

Mind Maps explores how mental health conditions have been diagnosed and treated over the past 250 years. Divided into four episodes between 1780 and 2014, this exhibition looks at key breakthroughs in scientists’ understanding of the mind and the tools and methods of treatment that have been developed, from Mesmerism to Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) and Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) bringing visitors up to date with the latest cutting edge research and its applications.

The small show is everything but dull and scholarly: controversial treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy and poisonous nerve ‘tonics’ are followed by pendulum measuring the speed of thoughts, Pavlov’s experiments on conditional reflexes and by Freud and his couch.

Every single object in the exhibition comes with a fascinating and at times chilling story. The only criticism i’m ready to make about Mind Maps is that ongoing journey into the mysteries of the brain and the nervous system would benefit from a less dim and confined exhibition space.

Highlights from the exhibition:

Frog Pistol, invented 1860s. Image courtesy Science Museum

Frog Pistol, invented 1860s. Image courtesy Science Museum

The artefact i found most puzzling was the ‘frog pistol’ developed by German scientist Emil du Bois-Reymond to demontrate ‘animal electricity’ to his students.

A fresh frog leg was placed on the glass plate inside the tube, with the nerve ends connected to the keys on the top of the pistol grip. When these keys were depressed, a contact was made and the leg kicked back as it if had been electrified.

The small pistol instrument was of course inspired by the work of Luigi Galvani. In the 1780s, the Italian doctor discovered that sparks of electricity caused dead frogs’ legs to twitch, leading him to propose that electrical energy was intrinsic to biological matter. Some of the instruments used by Galvani in his pioneering studies of nerve activity are presented in the exhibition, they haven’t been displayed in public for more than a century.

Amuletic dried frog in a silk bag from early 20th century south Devon. Photo Science Museum blog

Amuletic dried frog in a silk bag from early 20th century south Devon. Photo Science Museum blog

The nerve/frog connection doesn’t stop here. A dried frog inside a silk pouch is a testimony to the resilience of folk medicine in the 20th century, the essicated amphibian was carried around the neck ‘to prevent fits and seizures.’

Detail of an anatomical table displaying human nerves, dissected at the University of Padua in the 17th century (image Fresh eye on London)

Detail of an anatomical table displaying human nerves, dissected at the University of Padua in the 17th century (image Fresh eye on London)

Let’s keep on the macabre mood with this 17th century dissection table from Padua with all the nerves of (presumably) an executed criminal laid out on it to form a map of the nervous system on a varnished wooden panel.

Cavallo-style electrical generator, made by George Adams, London, 1780-84. Object no. 1889-29 © Science Museum

Cavallo-style electrical generator, made by George Adams, London, 1780-84. Object no. 1889-29 © Science Museum

Tiberius Cavallo, a leading European authority on medical electricity, designed this compact electrical generator and its accessories, including the ‘medical bottle’ that regulated the shocks it administered. Turning the glass cylinder built up a static electric charge in the metal collector on the side of the machine.

D’Arsonval cage from Riviere’s clinic, Paris. Image courtesy Science Museum

D’Arsonval cage from Riviere’s clinic, Paris. Image courtesy Science Museum

The patient stood inside the D’Arsonval cage while harmless high-frequency alternating current from the tesla coil on a desk pulsed around the metal framework, generating powerful electromagnetic fields inside the body. The treatment was claimed to stimulate metabolism, reduce obesity and eczema, and temporarily relieve nervous pains.

The cage was only one of the many devices that Dr J-A Rivière, “electrotherapist and pacifist”, used in the 1890s. His Paris clinic specialized in ‘physical’ treatments involving water, air, heat, light, electricity and after 1895, the newly discovered X-rays. Patients were seated in electric chairs, flooded with electric light or plunged into electrified bathtubs.

Bottle of “Ner-Vigor”, with instructions, in original carton, by the Anglo-American Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. Image courtesy Science Museum

Bottle of “Ner-Vigor”, with instructions, in original carton, by the Anglo-American Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. Image courtesy Science Museum

Huxley’s ‘Ner-Vigor’ was used between 1892-1943 for “strengthening the nerves.” Like some other medical products of the period, it contains a very small measure of the strychnine poison.

Nervone nerve nutrient, 1924-49. Object no. 1988-317/165 © Science Museum

Nervone nerve nutrient, 1924-49. Object no. 1988-317/165 © Science Museum

The Nervone ‘nerve nutrient’ was launched in the 1920s as an alternative to harmful nerve tonics and was still being sold in the 1960s when it was replaced by new anti-anxiety and depression drugs such as Valium.

Sherrington’s cat model, c. 1920-30. Object No: 1999-917 © Science Museum

Sherrington’s cat model, c. 1920-30. Object No: 1999-917 © Science Museum

Nerve scientist and Nobel Prize winner Charles Sherrington was fascinated by the way cats kept their balance while negotiating obstacles at speed. This model was used to illustrate how the cat’s eyes, whiskers, neck, legs and tail continued to work together even when the ‘highest’ portion of its brain had been removed.

Electroconvulsive therapy machine made in the 1940s for the Burden Neurological Institute

Electroconvulsive therapy machine made in the 1940s for the Burden Neurological Institute

The period that followed the Second World War saw the rise of several controversial treatments, including electro-convulsive therapy (where electricity is used to induce a brain seizure) and lobotomy.

Equipment for conducting an electronic lobotomy, 1962

Equipment for conducting an electronic lobotomy, 1962

The machine was designed to deliver just enough current to a gold electrode to make a peppercorn sized hole in the brain. This technique, also known as leucotomy, was a more precise form of lobotomy. It was used from the early 1960s to treat patients with uncontrollable anxiety.

EEG hairnet. Image courtesy Science Museum

EEG hairnet. Image courtesy Science Museum

Electroencephalography (EEG) remains an essential element of the psychology laboratory. It is frequently used in conjunction with brain scanning.

Lecuir’s battery, 1880-1920. Photo courtesy Science Museum, London

Lecuir’s battery, 1880-1920. Photo courtesy Science Museum, London

Batteries to stimulate nervous energy sometimes also featured religious symbols, because mental health needs all the help it can get, right?

Mind Maps: Stories from Psychology is free and runs at the Science Museum in London until 10 June.