Last weekend i was in Leiden, a short train trip away from Amsterdam, for the opening of an exhibition of the winning projects of the third edition of the Designers & Artists 4 Genomics Award.

The DA4GA give artists the opportunity to develop ambitious projects in cooperation with life science institutions carrying out research into the genetic makeup of people, animals, plants and microorganisms.

Charlotte donating skin to Christine Mummery’s laboratory in front of an audience at the Theatrum Anatomicum at the Waag Society in Amsterdam. Photos by James Read and Arne Kuilman

Charlotte donating skin to Christine Mummery’s laboratory in front of an audience at the Theatrum Anatomicum at the Waag Society in Amsterdam. Photos by James Read and Arne Kuilman

Charlotte donating blood to Christine Mummery’s laboratory in front of an audience at the Theatrum Anatomicum at the Waag Society in Amsterdam. Photos by James Read

Charlotte donating blood to Christine Mummery’s laboratory in front of an audience at the Theatrum Anatomicum at the Waag Society in Amsterdam. Photos by James Read

One of the recipients of the award is Charlotte Jarvis who used her own body to demystify the processes and challenge the prejudices and misunderstandings that surround stem cell technology.

Ergo Sum started as a performance at the WAAG Society in Amsterdam. In front of the public, the artist donated parts of her body to stem cell research. Blood, skin and urine samples were taken and sent to the stem cell research laboratory at The Leiden University Medical Centre iPSC Core Facility headed by Prof. Dr. Christine Mummery.

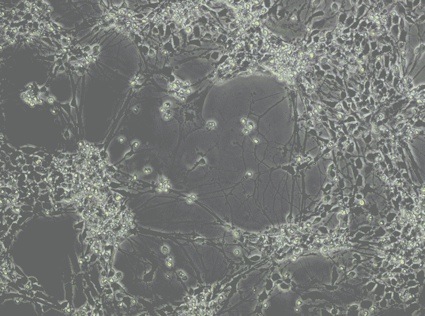

The scientists then transformed the samples into induced pluripotent stem cells, which in turn have been programmed to grow into cells with different functions such as heart, brain and vascular cells.

The whole process used the innovation which earned John Gurdon and Shinya Yamanaka a joint Nobel Prize last year. The two scientists are indeed behind the discovery that adult, specialised cells can be reprogrammed and turned back into embryo-like stem cells that can become virtually any cell type and thus develop into any tissue of the body.

The pluripotent stem cells offer an alternative to using embryonic stem cells, removing the ethical questions and controversies that surrounded the use of embryonic stem cells.

Brain cells grown from stem cells derived from Charlotte’s skin

Brain cells grown from stem cells derived from Charlotte’s skin

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

But let’s get back to Charlotte’s stem cells. Copies are now kept by the university for scientists to use in their research. And because the cells can be stored for an unlimited period, they are immortal. The ones that are on view at the exhibition in Leiden right now have to be kept alive by a team of scientists who regularly visit the exhibition space to care for the cells.

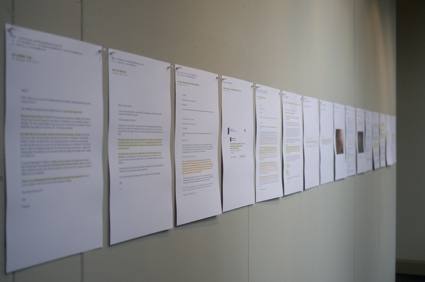

The synthesized body parts (now brain, heart and blood cells) are kept in an incubator made especially by a company specialized in museum displays as traditional incubator don’t have a window that would allow the public to have a peak inside. The cells are accompanied by videos, prints of email exchanges, photos and other items that document the whole story of the project.

Ergo Sum is a biological self-portrait; a second self; biologically and genetically ‘Charlotte’ although also ‘alien’ to her – as these cells have never actually been inside her body.

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

You first idea was to donate your eggs for the project but the scientists told you this might not only be illegal but also unnecessary. Could you explain why the eggs were unsuitable for the experiment and what the lab used in the end?

In the first instance I was unable to donate an egg because of the birth control I take. I have a three monthly injection (the DEPPO) which works by stopping egg production. It can take a year for your body to start producing eggs again after stopping the DEPPO, so I would not have been able to produce an egg in time for the project.

However, there were also ethical reasons for not donating an egg. I believe fervently in the use of embryos for scientific research, as of course do the scientists I work with. They have to fight for the right to use embryos in their research and under no circumstances would I do anything to jeopardise that. The use of embryos for artistic purposes is a different moral question. I felt that it would have been wrong (and potentially damaging to the scientists working on the project) to confuse those two ethical questions by making an art project utilising the scientific method for making embryonic stem cells.

What we used instead was stem cells derived from adult tissue. These are called Induced Pluripotant Stem Cells (IPSCs) and it is this technology that won the Nobel Prize last year. I donated skin, blood and urine to the lab. The lab was then able (using this new and wonderous technology) to send those cells back to how they were when I was a foetus – to turn them back into the stem cells they had been roughly 29 years ago. You could call it cellular time travel! I find our ability to do this completely awe inspiring.

Scars from biopsy 11/03/13

Scars from biopsy 11/03/13

Now that you’ve finally met your ‘second self, your dopplegänger, do you feel you have some kind of connection to it?

Seeing my heart cells beating was a unique experience – especially the first time I saw it. There is something that feels distinctly ‘alive’ about the beating heart cells and something quite extraordinary about seeing part of your own heart beating and living outside your body. But in general I would say that I feel no more connected to my second self than I would any other self portrait. I do not feel that these parts of me are sacred in some way, or even that they really belong to me in anything other than the genetic sense. That is really the point of the project – to question how we build our identity as humans and how that might change in the future. This may sound obvious, but I have learnt that I am more than the sum of my parts; that just because something has my heart, my brain and my flowing blood it is not ‘me’ and it is not a human.

Thanks Charlotte!

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

Charlotte Jarvis, Ergo Sum, 2013 (exhibition at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden.) Photo by James Read

Ergo Sum and the other winning projects of DA4GA are on view until 15 December at Raamsteeg2 in Leiden, in The Netherlands. Ergo Sum is funded by the Netherlands Genomics Initiative.