There is a spectacularly informative and macabre exhibition at the London Museum right now. Its title is suggestive enough: Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men.

Skull saw, c. 1831-1870 © Science Museum, Science & Society Picture Library

Skull saw, c. 1831-1870 © Science Museum, Science & Society Picture Library

Resurrection men were body snatchers who often worked in gangs to steal corpses from mortuaries and to dig up recently buried corpses to supply anatomy schools with bodies to dissect and study. Unsurprisingly, the poor, often hastily buried, were easier to unearth and carry to the nearest anatomy school.

Before the Anatomy Act of 1832, the only bodies that hospitals were legally allowed to use for surgeon training were the ones of executed criminals. And because the gallows only provided surgeons and anatomy schools with a few bodies each year, the medical profession had to resort to illegal means to get a practical understanding of human anatomy. Surgery was a dirty and agonizing affair back then. There was no anaesthetic nor antiseptic and even if the operation went well, the patient could still die from shock, loss of blood or infection. Surgeons had to be fast, their gesture confident and for that, they needed bodies on which to practice.

Some resurrection men were more unscrupulous than other. A handful even killed people to provide the corpses needed for surgery practice. The most famous case was the one of Thomas Williams and John Bishop who murdered 16 people and sold the bodies of their victims to science. They were convicted in 1831 and the irony is that after their execution, their own corpses ended up on the surgeon’s table. The exhibition is showing fragments of their tattooed skin and even a slice of the brain of infamous body snatcher and murderer William Burke.

To end the ensuing public hysteria, the parliament passed the Anatomy Act in 1832. It expanded the legal supply of bodies to “unclaimed” corpse from hospitals, workhouses or prisons. Once, again, it was the poor who usually ended up on the anatomy lesson table.

Fragment of tattooed skin from John Bishop or Thomas Williams. Photograph: Science Museum

Fragment of tattooed skin from John Bishop or Thomas Williams. Photograph: Science Museum

Amputation saw, reputedly the property of the English surgeon George ‘Graveyard’ Walker, c. 1800. Courtesy Science Museum, Science and Society

Amputation saw, reputedly the property of the English surgeon George ‘Graveyard’ Walker, c. 1800. Courtesy Science Museum, Science and Society

Because they feared to have their body or the body of a loved one stolen by resurrection men, people defended their right to ‘rest in peace’ by being buried in gilded iron coffin, outfitted with locks, and graveyards were protected by fearsome “man-traps”, loaded pistols with trip-wire, etc.

19th-century man trap © Museum of London (image History Extra)

19th-century man trap © Museum of London (image History Extra)

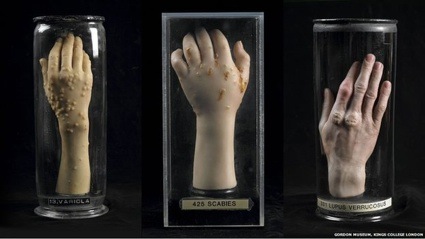

Classes with direct contact with contagious diseases were not feasible so models were used instead. Joseph Towne made hundreds of wax samples, cast from living patients, in order to aid the students’ study (image BBC news)

Classes with direct contact with contagious diseases were not feasible so models were used instead. Joseph Towne made hundreds of wax samples, cast from living patients, in order to aid the students’ study (image BBC news)

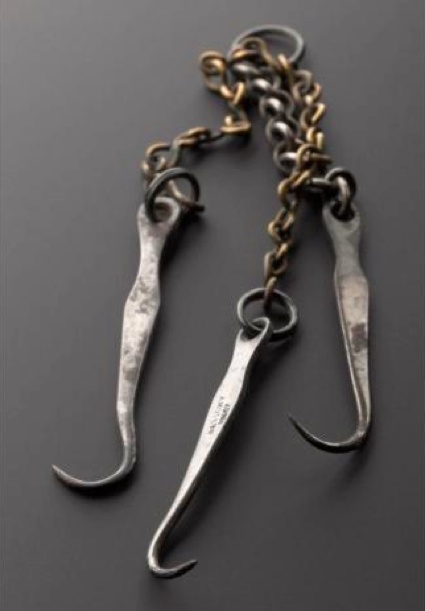

Dissection hooks © Science Museum, Science & Society Picture Library

Dissection hooks © Science Museum, Science & Society Picture Library

Post-mortem instruments, c1850 © The Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons

Post-mortem instruments, c1850 © The Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons

The exhibition starts on firm historical ground but by the third room you realize that the theme finds an echo in 21st century Britain. First of all because Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men was inspired by a recent event: the finding in 2006 of a burial ground at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. They remains excavated by archaeologists showed marks of dissection, autopsy and amputation, along with skeletons of animals dissected for comparative anatomy. The discovery suggests that the hospital dissected the body of diseased patients for surgery practice both before and after it was legal to do so.

The second reason is that the Anatomy Act was only replaced in 2004 by the Human Tissue Act which ensures that access to corpses for medical science in the UK is now regulated by the Human Tissue Authority. But even today, demands for bodies to either dissect or use as a source of organ for transplantation far exceeds the offer.

Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men, as you can guess, often verges on the gruesome but it is also remarkably instructive and engaging. I’m leaving you with a few more images from the show, starting with the work that impressed me the most:

Conservator Jill Barnard installs the 19th-century anatomical plaster cast of convicted murderer James Legg. Photograph: Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images

Conservator Jill Barnard installs the 19th-century anatomical plaster cast of convicted murderer James Legg. Photograph: Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images

Anatomy classes also took part at the Royal Academy of Arts. In 1801, 3 artists demonstrated that most depictions of the Crucifixion were anatomically incorrect. With the assistance of a surgeon, they acquired the body of a criminal and nailed it into position, flayed to remove all skin and then cast in plaster. The cast was never intended as a work of art but is otherwise on display at the Royal Academy of Art.

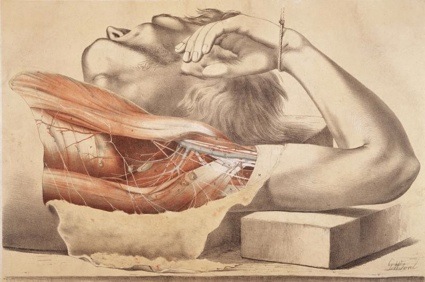

The Superficial muscles of the thorax and the axilla, 1876. Photo Wellcome Library

The Superficial muscles of the thorax and the axilla, 1876. Photo Wellcome Library

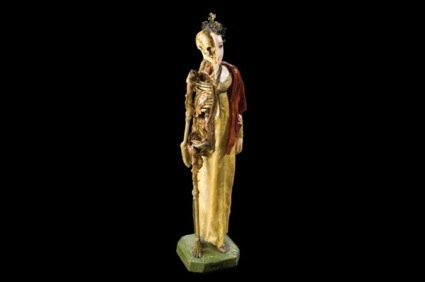

Female wax anatomic model showing internal organs, 1818. Courtesy Science Museum, Science and Society Picture Library

Female wax anatomic model showing internal organs, 1818. Courtesy Science Museum, Science and Society Picture Library

Front view of dissection table © Science Museum, Science & Society Picture Library

Front view of dissection table © Science Museum, Science & Society Picture Library

Female momento mori © Science Museum, Science & Society Picture Library

Female momento mori © Science Museum, Science & Society Picture Library

Excavation of tightly packed burials from the later part of the hospital cemetery. Photo Museum of London Archaeology

Excavation of tightly packed burials from the later part of the hospital cemetery. Photo Museum of London Archaeology

View of the exhibition space (image Visit London)

View of the exhibition space (image Visit London)

View of the exhibition space (image BBC news)

View of the exhibition space (image BBC news)

Doctors, Dissection and Resurrection Men is up until April 14 at the Museum of London.

Related story: Brains: The Mind as Matter.