Photo: Thijs de Lange

Photo: Thijs de Lange

Genk is a city almost entirely devoid of any grace but it is also the site of the 9th edition of Manifesta, the European Biennial of Contemporary Art. And who needs grace and glamour when you have an exhibition as sensational as as the one that Cuauhtémoc Medina curated in a disused coal mine at the outskirt of the city?

To be fair, i suspect that the spectacularity of the Manifesta 9 show owes much to the venue. The art deco architecture of the ex-headquarters of the André Dumont mine is so stunningly dilapidated, it silences any flaw in the show.

Instead of showcasing exclusively the latest and the very best in contemporary art, the exhibition, titled The Deep of the Modern, is articulated as a triptych. The first floor pays homage to the cultural and social heritage of Limburg mining industry. It had its surprises and joys but maybe my enthusiasm comes from the fact that I grew up in an ex-coal mining region and other visitors will probably have a very different experience of this section of the show.

Film still, from Belgavox, Het zwarte goud van de Kempen (The Black Gold of the Campine”), 1951

Film still, from Belgavox, Het zwarte goud van de Kempen (The Black Gold of the Campine”), 1951

Photo: Thijs de Lange

Photo: Thijs de Lange

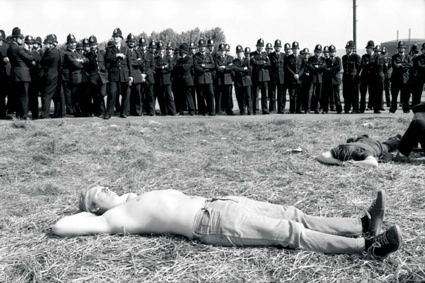

Upstairs is an ‘art historical section’ with works from the 19th and 20th Centuries that looked at the coal industry. From the figure of the miner Alexey Stakhanov and the “Life is Joyous Comrade” slogan to Marcel Broodthaers’ critique of Belgian mussels & coal identity. From Bernd and Hiller Becher’s b&w photographs of mining units and buildings to Mike Figgis and Jeremy Deller’s Battle of Orgreave. Some of the works in the space –such as Deller and Figgis’ re-enactment of the 1984 confrontation between miners and police, the documentary about the shooting of Belgian miners during a 1966 strike and the photo documentation of picketing miners in England in the mid-80s– find a sad and direct echo in this week’s news of the police opening fire on striking miners at a platinum mine in South Africa.

The top floor hosts the work of artists who were invited to extend the mining theme and explore the legacy of industrialization and global systems of production.

The result is a very literal, very dark exhibition. But Manifesta 9 managed to devise an inventive formula at a time when most art critics question the raison d’être of the (mushrooming) art biennials.

I’m going to cover the contemporary art section of the biennial in another article. This one is merely an introduction and a quick / copy paste of some of the works i liked in the two ‘historical’ parts of the show. In no particular order, mixing modern art, anecdotes, and historical figures.

First the setting:

Manifesta9, surroundings Waterschei. Photo Kristof Vrancken

Manifesta9, surroundings Waterschei. Photo Kristof Vrancken

Photo Kristof Vrancken

Photo Kristof Vrancken

2012 Architects & Refunc, architectural implementations in the Manifesta 9 exhibition venue, 2012. Photo Kristof Vrancken

2012 Architects & Refunc, architectural implementations in the Manifesta 9 exhibition venue, 2012. Photo Kristof Vrancken

1200 coal sacks were hanging from the ceiling, an homage to Marcel Duchamp‘s 1938 installation 1200 Coal Sacks, intended to trash the ambiance of an art gallery and bring dust and dirt inside the ‘white box’.

Age of Coal, Coal Sack Ceiling – Hommage to Marcel Duchamp. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Age of Coal, Coal Sack Ceiling – Hommage to Marcel Duchamp. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Age of Coal, Coal Sack Ceiling – Hommage to Marcel Duchamp. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Age of Coal, Coal Sack Ceiling – Hommage to Marcel Duchamp. Photo by Kristof Vrancken

Speaking of dirt….

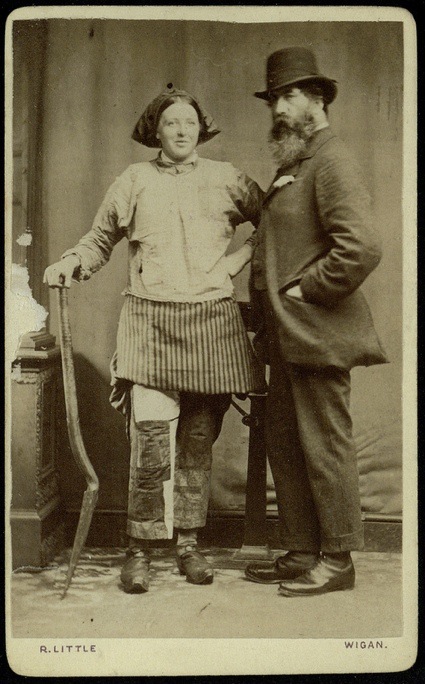

Victorian barrister and writer Arthur Munby is famous for his photographs of working girls who posed, with dirt on their face and soiled clothes, in front of the white backdrop of his studio. Munby might have been a mysophiliac, a person who finds dirt sexually attractive. Munby secretly married Hannah Cullwick, a maid who posed for him scrubbing the floor, as a chimney sweep or as a farm girl.

Arthur Munby, Black Album 3, Ellen Grounds, a ‘brow-wench’ at Pearson and Knowle’s Pits, Wigan, 1873. Credit: Trinity College Library, Cambridge

Arthur Munby, Black Album 3, Ellen Grounds, a ‘brow-wench’ at Pearson and Knowle’s Pits, Wigan, 1873. Credit: Trinity College Library, Cambridge

Igor Grubic’s Angels with Dirty Faces is an homage to the Kolubara miners’ strike that eventually brought down the Miloševi´c regime, and sparked the end of socialism in Yugoslavia. At the time, the Kolubara mine was the largest supplier of lignite coal in Serbia, producing almost half of the country’s electricity. The workers are portrayed against the backdrop of decommissioned factories or industrial sites.

Igor Grubić, Angels with Dirty Faces, 2006

Igor Grubić, Angels with Dirty Faces, 2006

Igor Grubić, Angels with Dirty Faces, 2006. View of the exhibition space, photo Kristof Vrancken

Igor Grubić, Angels with Dirty Faces, 2006. View of the exhibition space, photo Kristof Vrancken

Oh! God! Even Rocco Granata was participating to the biennale. Granata was born in Italy but immigrated to Belgium when he was ten and later briefly worked in the mine. In 1958 Granata wrote and released the song Marina. It became an international success. The song has subsequently been performed by such artists as Louis Armstrong and Dalida.

A whole area of the first floor was dedicated to Granata. Click on the video below at your own risk. I did that 3 days ago and the song hasn’t left my head ever since.

I might have danced on the late ’80s remix version back when i was a growing up in that other mining region of Belgium.

In the mid-80s, Keith Pattinson documented the miners’ strike in the Easington Colliery

Keith Pattison, Striking miners on the picket line

Keith Pattison, Striking miners on the picket line

Don MacPhee, Miners sunbathing at Orgreave coking plant, 1984

Don MacPhee, Miners sunbathing at Orgreave coking plant, 1984

Manifesta 9, Age of Coal overview, Historical Gallery

Manifesta 9, Age of Coal overview, Historical Gallery

Poster Celebrating Stakhanov, 1975

Poster Celebrating Stakhanov, 1975

I found the video below very moving: For Sounds from Beneath records a male colliery choir singing the subterranean sounds of a working mine. A colliery in East Kent, once populated with workers, machines and the sounds of their activities transforms into an amphitheatre haunted by a stranger, resonating sounds of explosions in the ground, machines cutting the coal-face, shovels scratching the earth and the distant melody of the Miner’s Lament, all sung by the choir grouping in formations reminiscent of picket lines.

Mikhail Karikis with Uriel Orlow and featuring Snowdown Choir, Sounds from Beneath, 2010

Manifesta 9, The European Biennial of Contemporary Art, is on until 30 September, in Genk, Belgium.