I finally went to the Wellcome Collection to see Superhuman – An exhibition exploring human enhancement.

Glasses, lipstick, false teeth, the contraceptive pill and even your mobile phone – we take for granted how commonplace human enhancements are. Current scientific developments point to a future where cognitive enhancers and medical nanorobots will be widespread as we seek to augment our beauty, intelligence and health.

Superhuman takes a broad and playful look at our obsession with being the best we can be. Items on display range from an ancient Egyptian prosthetic toe to a packet of Viagra, alongside contributions from artists such as Matthew Barney and scientists, ethicists and commentators working at the cutting edge of this most exciting, and feared, area of modern science.

Trailer of the exhibition

Yes! Superhuman is all of the above and much more. In fact, the exhibition gives visitors a lot to chew on. In no particular order, Super human discusses: The definition of enhancement (is the smart phone an enhancement of our body and brain?) Missing body parts that get replaced -even if their function is forever lost- in an attempt to ‘normalize’ a body. Man and Machine and the perspective of becoming cyborgs. The Superheroes that anticipate transhumanism. A future of humanity timeline. And of course a focus on Sport.

Superhuman gallery shots: Vivienne Westwood’s ghillie shoes (via Londonist)

Superhuman gallery shots: Vivienne Westwood’s ghillie shoes (via Londonist)

Superhuman gallery shots (via Londonist)

Superhuman gallery shots (via Londonist)

It’s not all RoboCop and Spider-Man though. The exhibition opens on a warning: a statue of Icarus that reminds us that every attempt to improve our bodies and brains comes with its own set of pitfalls and ethical questions. High heel shoes elevate us but too high, they make walking a challenge. Tom Hicks won the 1904 Olympic marathon after having been doped with strychnine mixed with brandy (performance-enhancing drugs were allowed at the beginning of the 20th century.) He collapsed on the line.

Prosthetic limbs are a particularly striking case of the perils and advantages of enhancements.

Aimee Mullins, the double-amputee model and Paralympian, sees her condition as an opportunity. With each new set of legs comes new powers, new function and a new identity.

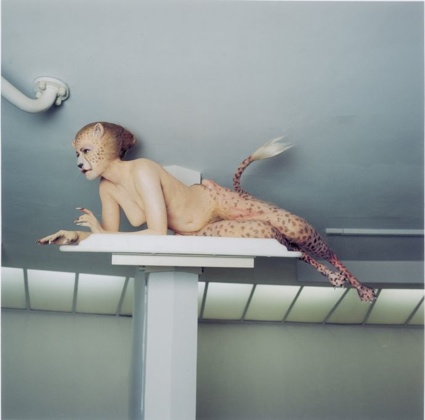

Aimee Mullins in Matthew Barney’s Cremaster 3, 2002

Aimee Mullins in Matthew Barney’s Cremaster 3, 2002

Oscar Pistorius can now compete in mainstream athletics using his ‘blade’ legs. His performances prompted the question: does his carbon-fiber give him an unfair advantage over other runners?

More questions arise if we look beyond the case of Pistorius: Will the distinction between Olympics and Paralympics be erased one day? Or will prosthetics become so advanced that they will be seen as an advantage over the ‘natural’ body?

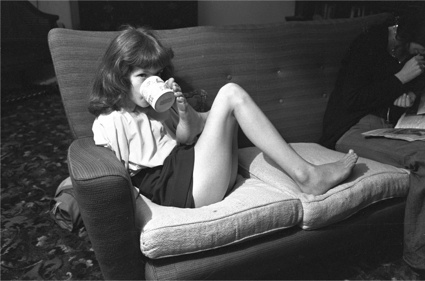

Philippa Verney Drinking Coffee with her Foot. Credit: Photograph by Frank Hermann /The Sunday Times/NI Syndication

Philippa Verney Drinking Coffee with her Foot. Credit: Photograph by Frank Hermann /The Sunday Times/NI Syndication

At the opposite end of the spectrum are the prosthetic limbs whose sole function was cosmetic. They provided no relief nor aid. Such were the prostheses designed for the “Thalidomide babies”, these artificial limbs were so bulky and unhelpful that many children eventually abandoned them.

Thalidomide was a sedative drug given to pregnant women to alleviate morning sickness. It was sold from 1957 until 1961, when it was withdrawn after being found that the drug interfered with the development of a baby’s limbs. During that short period, 10,000 children in 46 countries were born with deformities as a consequence of thalidomide use.

The government funded the design of prostheses for children affected by thalidomide in order to make them look ‘normal’. The experimental arm and leg prostheses had to be custom-made but they were clunky and uncomfortable. They replicated the aspect of the limb but were not able to reproduce its function. Many children refused to wear them.

Pair of artificial arms for a child, Roehampton, England, 1964. Credits: Science Museum London

Pair of artificial arms for a child, Roehampton, England, 1964. Credits: Science Museum London

Pair of artificial legs for a child, Roehampton, 1966. Photograph: Science Museum, London

Pair of artificial legs for a child, Roehampton, 1966. Photograph: Science Museum, London

Both Mullins’ experience as well as the history of the Thalidomide babies makes us realize that the role of prostheses nowadays is not so much to give a sense of ‘normality’ (at the detriment sometimes of the wearer’s comfort) but to accommodate a difference and allow the wearer to embrace a new identity.

A still from Terry Wiles footage from the films of Dr Ian Fletcher, Senior Medical Officer in the Artificial limb Fitting Centre at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Roehampton, c. 1965. Picture: Wellcome Library, London

A still from Terry Wiles footage from the films of Dr Ian Fletcher, Senior Medical Officer in the Artificial limb Fitting Centre at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Roehampton, c. 1965. Picture: Wellcome Library, London

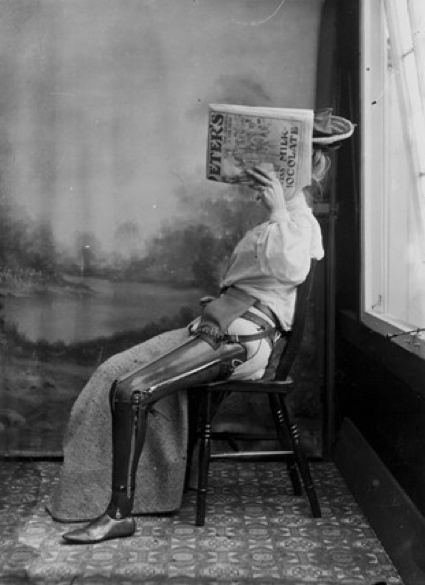

Speaking of prosthetic limbs. I found these images of elegant women showing their wooden leg but not their face extremely moving. The legs were crafted by James Gillingham (1839-1924), a shoemaker based in Chard, Somerset. Gillingham first started making artificial limbs after a local man lost an arm firing a cannon for a celebratory salute in 1863.

Studio photograph of a seated woman wearing an artificial leg manufactured by James Gillingham

Studio photograph of a seated woman wearing an artificial leg manufactured by James Gillingham

Woman wearing an Artificial Leg, 1890-1910. Manufatured by James Gillingham of Chard © Science Museum / Science & Society

Woman wearing an Artificial Leg, 1890-1910. Manufatured by James Gillingham of Chard © Science Museum / Science & Society

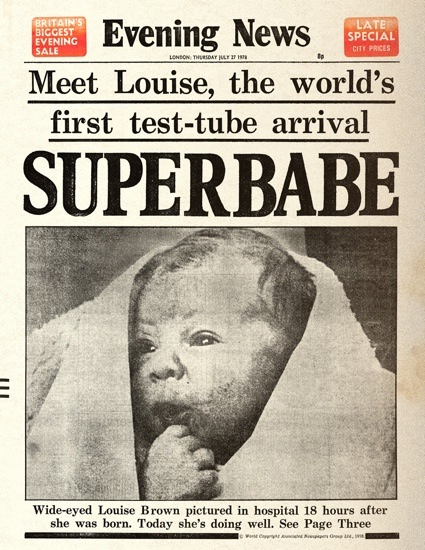

One of the most pertinent points developed in the exhibition is the shift in perception: what was regarded as exceptional is now ordinary. IVF treatment which made the covers of newspapers not so long ago is now a relatively routine procedure (in 2009, 12 714 babies were born in the UK through IVF.) False teeth and contraceptive pills are now so common we don’t see them as enhancements anymore.

Would someone from the 19th century regard us as superhuman? What will the ‘normal’ people of tomorrow be like? Look like? What will they be able to do better and faster than us?

Meet Louise, the world’s first test tube arrival. Evening News, 27 July 1978

Meet Louise, the world’s first test tube arrival. Evening News, 27 July 1978

Quick round-up of the stories, images and ideas i discovered in the exhibition:

Ivory denture with human teeth Credit: British Dental Association Museum

Ivory denture with human teeth Credit: British Dental Association Museum

The set of teeth above were known as Waterloo Teeth. Replacement teeth were traditionally made from ivory (hippopotamus, walrus or elephant). However such teeth deteriorated faster than real teeth. The best set of dentures in the early 19th century were made with real human teeth set on an ivory base. Some of these teeth were scavenged from dead soldiers on battlefields.

Whizzinator (tan). Manufactured by Alternative Lifestyle Systems

Whizzinator (tan). Manufactured by Alternative Lifestyle Systems

The Whizzinator kit was originally marketed as a way to fraudulently defeat drug tests. The kit comes with dried urine and syringe, heater packs (to keep the urine at body temperature) and a false penis (available in several skin tones). The manufacturers were prosecuted for conspiracy to defraud the US government; the device is now sold as a sex toy. Should you be interested…

A motorised wheelchair with proximity detectors, designed in 1997. Photograph: The Estate of Donald G Rodney

A motorised wheelchair with proximity detectors, designed in 1997. Photograph: The Estate of Donald G Rodney

Artist Donald Rodney was born with sickle-cell anaemia, a debilitating disease of the blood. Psalms is a wheelchair programmed to explore the floor space of the gallery and symbolises the presence of the artist when he was too sick to attend the opening of his own exhibitions.

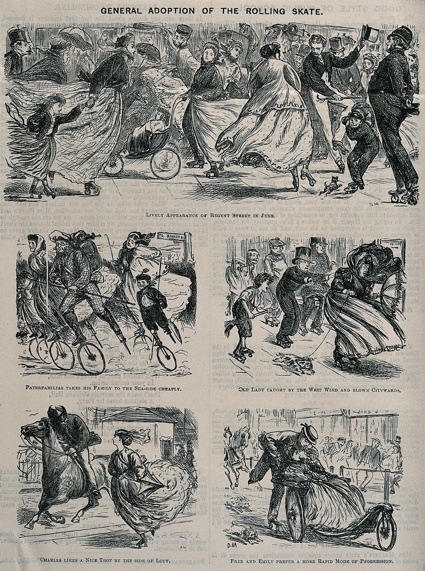

‘General Adoption of the Rolling Skate’.Illustration by George Du Maurier, ‘Punch’, 1866. Wellcome Library

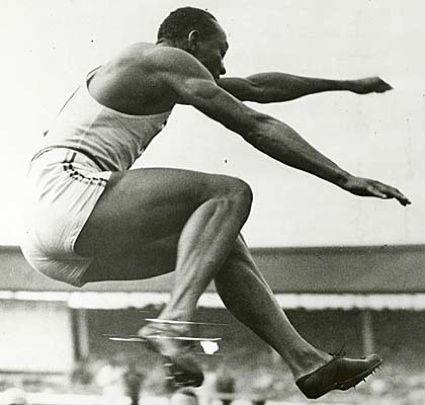

Jesse Owens competing at the 1936 Olympics. © The Ohio State University Archives

Jesse Owens competing at the 1936 Olympics. © The Ohio State University Archives

During the Berlin Olympics of 1936, Adolf Dassler (founder of Adidas) approached Jesse Owens and convinced him to wear a pair of his track shoes in order to improve his performance.

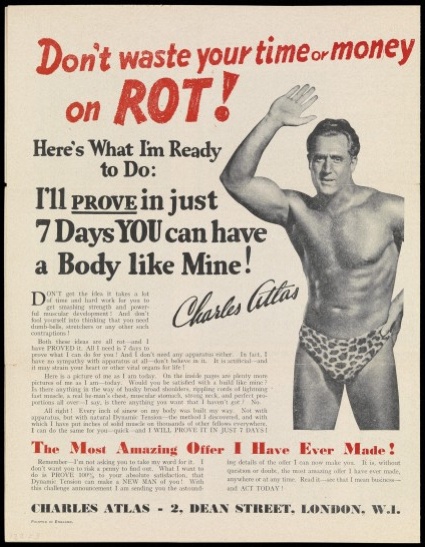

Charles Atlas, Don”t waste your time or money on ROT!, 1939. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Charles Atlas, Don”t waste your time or money on ROT!, 1939. Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

Legend has it that Charles Atlas used to be mocked for being skinny. He went on to change his body and develop a bodybuilding method and its associated exercise program that, allegedly, enabled weaklings to turn themselves into fit, strong men. He advertised his method in comic books from the 1940s and the campaign is regarded as one of the most longest-lasting ad campaigns of all time.

The image above shows one page of a correspondence course sent out in early 1939 giving instructions in how “in just 7 days YOU can have a body like mine” by using his Dynamic Tension program. The leaflet includes numerous photographs of Charles Atlas posing in leopardskin trunks and flexing his muscles.

Francesca Steele, Routine. Photo by Simon Keitch

Francesca Steele, Routine. Photo by Simon Keitch

For Routine, the artist Francesca Steele transformed her physique over a year through adoption of bodybuilding training and diet.

Francesca Steele, Routine. Photo by Simon Keitch

Francesca Steele, Routine. Photo by Simon Keitch

Prosthetic toe, Cartonnage, 600 BCE. British Museum

Prosthetic toe, Cartonnage, 600 BCE. British Museum

This artificial toe is one of only a few examples found on or buried with Egyptian mummies. It was initially thought to complete the body after death, essential for successfully passing over to the afterlife. However, signs of wear and repair suggest it may also have been used in life. Tests using a replica found it was possible for a volunteer who had lost their right big toe to walk successfully while wearing it, with the toe itself withstanding the pressure of use.

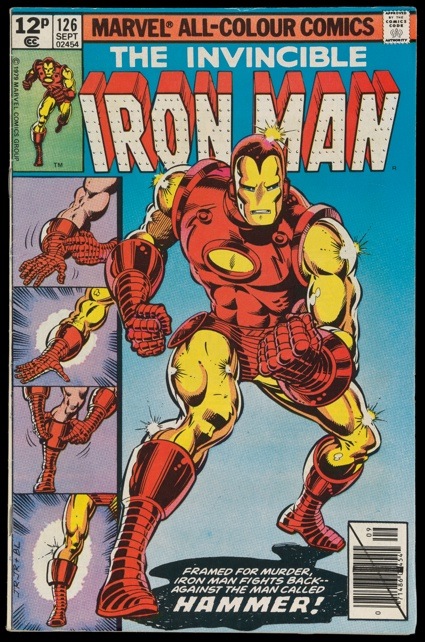

The Invincible Iron Man: The hammer strikes! David Michelinie, writer; John Romita Jr, penciller; Bob Layton, inker. Marvel Comics Group, 1979

The Invincible Iron Man: The hammer strikes! David Michelinie, writer; John Romita Jr, penciller; Bob Layton, inker. Marvel Comics Group, 1979

Many comic-book heroes seem to anticipate ‘transhumanism’ – the application of technology to humans to enhance their abilities. Iron Man is a cyborg who will die without his artificial heart and whose power comes from his high-tech suit. Spider-Man’s special abilities come from his artificially altered biology. And life imitates art: scientists are now developing powered exoskeleton suits to allow paraplegics to walk, while spider silk is providing the basis for new biomaterials used to repair knee cartilage.

Rebecca Horn, Scratching Both Walls at Once, 1974-1975. Image Tate London 2012

Rebecca Horn, Scratching Both Walls at Once, 1974-1975. Image Tate London 2012

Floris Kaayk, Metalosis Maligna

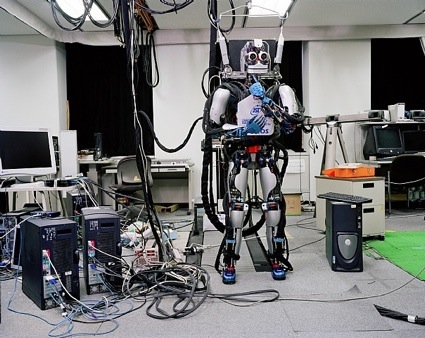

Yves Gellie, Human Version 2.0, 2007

Yves Gellie, Human Version 2.0, 2007

Yves Gellie, Human Version 2.0, 2007

Yves Gellie, Human Version 2.0, 2007

Yves Gellie toured the scientific research laboratories dedicated to the development of humanoid robots.

Yves Gellie, Human Version 2.0, 2007

Yves Gellie, Human Version 2.0, 2007

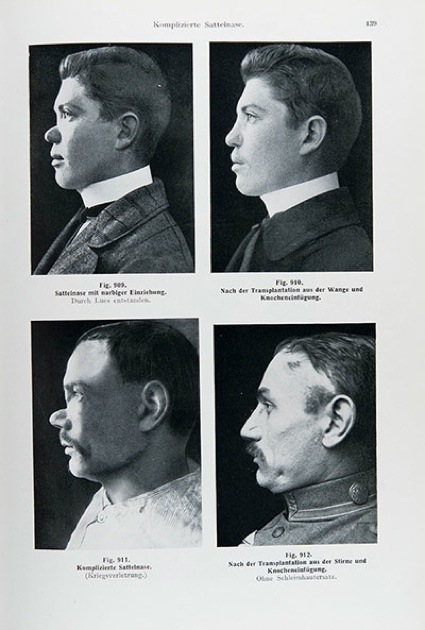

Nasal surgery before and after images, 1931. Photograph: Wellcome Library, London

Nasal surgery before and after images, 1931. Photograph: Wellcome Library, London

A knitted breast prosthesis designed by the Lactation Consultants of Great Britain and Beryl Tsang, knitted Louise Sargent in 2012. Photograph: Wellcome Image

A knitted breast prosthesis designed by the Lactation Consultants of Great Britain and Beryl Tsang, knitted Louise Sargent in 2012. Photograph: Wellcome Image

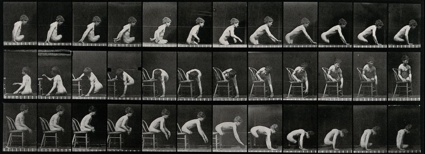

A double amputee climbing on to a chair, descending from a chair and moving. Photogravure after Eadweard Muybridge, 1887. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

A double amputee climbing on to a chair, descending from a chair and moving. Photogravure after Eadweard Muybridge, 1887. Credit: Wellcome Library, London

Also in the exhibition: The Immortal, life-support machines keeping each other alive. The machines are turned on daily but only for one hour (from 12.30 to 1.30 if i remember correctly.)

Evening Standard has photos of the opening.

Superhuman is at the Wellcome Collection until October 16, 2012.