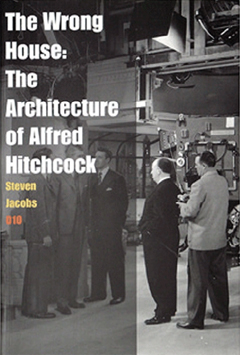

The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock, by Steven Jacobs (available on Amazon USA and UK.)

The Wrong House: The Architecture of Alfred Hitchcock, by Steven Jacobs (available on Amazon USA and UK.)

010 publishers write: In the films of Alfred Hitchcock, architecture plays an important role. Having worked as a set designer in the early 1920s, Hitchcock remained intensely concerned with the art direction of his films. In addition, the ‘master of suspense’ made some remarkable single-set films, such as Rope and Rear Window, that explicitly deal with the way the confines of the set relate to those of the architecture on screen. Spaces of confinement also turn up in the ‘Gothic plot’ of films in which the house is presented as an uncanny labyrinth and a trap. Furthermore, it became a Hitchcock hallmark to use famous monuments as the location for a climactic scene. Last but not least, Hitchcock used architectural motifs such as stairs and windows, which are closely connected to Hitchcockian narrative structures (suspense) or typical Hitchcock themes (voyeurism). Apart from dealing with these issues extensively, Steven Jacobs discusses at length a series of domestic buildings with the help of a number of reconstructed floor plans especially made for this publication.

1966 “Torn Curtain,” Director Alfred Hitchcock. 1966 Universal. – Image MPTV.net

1966 “Torn Curtain,” Director Alfred Hitchcock. 1966 Universal. – Image MPTV.net

This is one dangerous book for people like me who don’t need an excuse to jump in the sofa and watch a Hitchcock movie instead of staying in front of the computer to work. Still, no matter how many books have been written about the “Master of Suspense” i never felt compelled to read any. Until this one.

Author Steven Jacobs claimed that he had written a monograph about an non-existing architect which make more sense than one might think at first sight. After all, movie directors and production designers have been known for using film sets as an intermediary to reflect on the city of the future. Having designed more models than built houses didn’t prevent architectural studio Archigram to be one of the most influential and iconic architectural studios ever. Hitchcock didn’t advance the slightest step in that direction. His art did not explore possible or futuristic architecture but remained grounded in what was available at the time of films, with a marked preference for old-style furniture and bourgeois mansions (think Victorian or his own house near Guildford.)

Lobby Card from Vertigo (1963 reissue). Image tcmdb

Lobby Card from Vertigo (1963 reissue). Image tcmdb

The Wrong House (a title referring to the 1956 movie The Wrong Man) is roughly made of two parts.

The first part of the book, the theoretical one, is by far the most fascinating. It explains in details how Hitchcock regarded set design as crucial element of the drama, used both domestic elements and touristic sites as protagonists in the story but also extended the architectural language to camera movements and positions, editing and other cinematographic practices.

1954, Rear Window

1954, Rear Window

Most of the settings for his movies were mounted in studio, where Hitchcock had total control over the shooting conditions. The most bourgeois house was often represented as a space of oppression, danger and a provider of the uncanny. The interior is stuffed and closed, keys give the viewers access to the murder room, and each step on a stair advances the denouement as much as it delays it. Other buildings, even the public ones, are not necessarily safer, perversion lurks behind motel doors, museums are made for mysterious encounters.

1948 James Stewart, Alfred Hitchcock, and Cast on the set of “Rope.” 1948 Warner – Image MPTV.net

1948 James Stewart, Alfred Hitchcock, and Cast on the set of “Rope.” 1948 Warner – Image MPTV.net

In location shootings, the film director had a field day toying with crowds and playing with urban icons. The former gave him some great opportunities to insert his famous cameos. The later included the Golden Gate Bridge, the British Museum, the UN Headquarters, Mount Rushmore which are so intimately connected to the films shot there that it can be said that Hitchcock tailed tourism as much as it stimulated it.

Still from Vertigo, 1958

Still from Vertigo, 1958

1959, North by Northwest (via filmposters)

1959, North by Northwest (via filmposters)

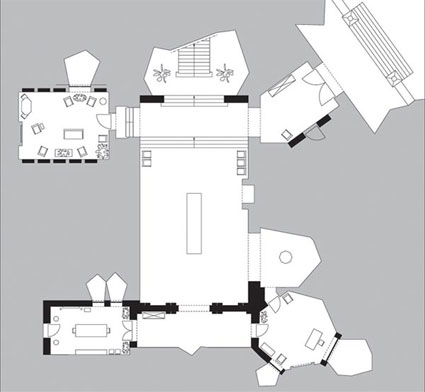

The second part of the book, made of case studies that dissect meticulously the architecture and internal design of 26 houses from 22 different films, is a bit overwhelming. When Jacobs hasn’t been able to trace drawings of sets built in the studio, he reconstructed the floor plans of these houses, mostly on the basis of what he saw in the films. Each movie is investigated from an architectural point of view. That’s how The Balestrero House in The Wrong Man is analyzed under the perspective of Kitchen sink claustrohpobia, Bates house and motel are defined as schizoid, Sebastian house in Notorious is a place for Nazi hominess and that’s how Rebecca discovers that Manderley is in fact Bluebeard’s Castle.

Plan of the ground floor of Manderley in the film Rebecca

Plan of the ground floor of Manderley in the film Rebecca

I wouldn’t say that The Wrong House is an architecture book. As i am much more interested in architecture than cinema i was surprised to see how metaphorically the term “architecture” was used along its pages. But then i also like to be surprised once in a while….