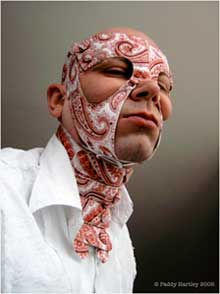

Back in 2004, i stumbled upon a project called The Face Corset. Designed by Paddy Hartley to simulate the effects of cosmetic surgery, they were one of his first comments on and explorations of cosmetic surgery and our culture’s obsession with beauty. Furthermore, the artist collaborated with Biomaterials Scientist Dr Ian Thompson to adapt the corsets into facial dressings that could protect and support the face during the recovery period after surgery or skin grafting.

Back in 2004, i stumbled upon a project called The Face Corset. Designed by Paddy Hartley to simulate the effects of cosmetic surgery, they were one of his first comments on and explorations of cosmetic surgery and our culture’s obsession with beauty. Furthermore, the artist collaborated with Biomaterials Scientist Dr Ian Thompson to adapt the corsets into facial dressings that could protect and support the face during the recovery period after surgery or skin grafting.

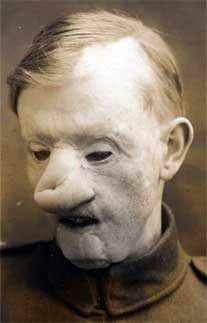

With Project Facade, the second step into this research, the artist is looking into the personal and surgical stories of soldiers who, disfigured in battle during the First World War, had to undergo pioneering surgical reconstruction. “The very nature of trench warfare, moreover, proved diabolically conducive to facial injuries: “[T]he…soldiers failed to understand the menace of the machine gun,” recalled Dr. Fred Albee, an American surgeon working in France. “They seemed to think they could pop their heads up over a trench and move quickly enough to dodge the hail of bullets.” (via)

Working from original patient and surgical notes along with personal family archive material of the men, Hartley designs, modifies and embroids uniforms similar to those the servicemen fought in. Each garment tells the fragmented personal history of a man who had to go back to his families with a seamed and shattered face.

Working in partnership with Gillies Archive Curator Dr Andrew Bamji at Queen Mary’s Hospital Sidcup and Dr Ian Thompson at in the Oral Maxillofacial Dept, Guys Hospital London, the project allows Hartley to examine and respond artistically to the origins of surgical facial reconstruction, compare current techniques in facial surgery and the development and implementation of bioactive materials for the repair of facial bone injuries.

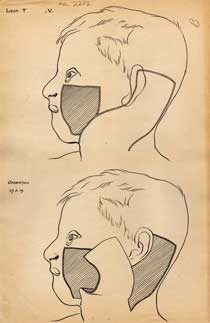

Victor T.

Victor T.

What prompted your interest in the origins of surgical facial reconstruction techniques?

Even though I trained in ceramics and sculpture, I’ve always been more interested in human biology, technology, and engineering, that sort of thing than in art. I see the Artistic/creative process as a vehicle for the examination and combination of ‘anything with everything’. So much of the work I produced at University and in my early career was about anything other than ‘Art or the Artist’. Examining the use/abuse of Steroid in bodybuilding, religious organizations shifting attitudes towards medical technologies and recently the origins of facial reconstruction.

Having seen some of my previous work using medical equipment, I was invited by the Victoria & Albert Museum in London in 2002 to exhibit work for an evening-long event called ‘Short Cuts to Beauty’ which consisted of a series of public demonstrations, presentations and debates on ‘beauty industries’ and their impact on society today. Not having anything appropriate for the event in my back catalogue, I proposed I make new work for the event and considering one of the topics up for discussion was extreme cosmetic surgery and the use of facial implants, it seemed appropriate to make work based around a hypothetical of facial surgery as taboo. What if it was considered taboo in today’s society to alter the structure of the face surgically for cosmetics alone? How could an individual radically alter the structure of the face without the use of surgery? Corsetry immediately sprang to mind (particularly as I left the V&A after my meeting I left via the Dress Gallery and saw the collection of corsets on display). If it was possible to alter and ‘train’ the structure of the body with a garment, could I do the same with a ‘facial corset’ to shift the soft tissue of the face?

Paddy Hartley’s studio

Paddy Hartley’s studio

So having never even sat at a sewing machine, I set about making patterns based on my own face (the only one readily available!) and getting to know the basics of garment construction. The original idea was to make ‘neutral’ looking garments from white fabric incorporating external ‘adornments’ using commercially available facial implants. This was how I came to meet Biomaterials Scientist Dr Ian Thompson at Imperial College London via recommendations from the Science Museum, London. I originally approached Ian to try and obtain some commercially available facial implants but when I saw the work he was doing making Bioactive glass facial implants for the repair of bone facial injuries, I thought I just had to incorporate these into the ‘Face Corsets’, which as it turns out, we did. As far as the Corsets themselves were concerned, an unexpected (yet with hindsight totally foreseeable outcome) was that the tighter the garment was fixed to the head, the more the wearer was able to reposition the exposed skin.

The presentation of the work at the V&A event really was the start of a long working relationship between Dr Thompson and myself. My skills in developing the casting of the implants with Ian coupled with his vision of the ‘Face Corsets’ as potential pressure dressings cemented our working relationship and the logical next step was to seek funding to pursue our collaboration. Obtaining our first grant from The Wellcome Trust allowed us to develop the work full-time for a year but if the truth be known, quite early in the project my interest turned to the origins of facial reconstruction.

First Face Corset and Paisley

First Face Corset and Paisley

How has the public reacted to the Face Corset when you exhibited the work?

Very mixed, sometimes with a raised eyebrow, sometimes with a knowing look, sometimes with a chuckle. Everyone brings their own interpretation which, to a certain degree is great because I didn’t intend to load the work with meaning. They are physical devices built around a ‘functional’ brief. What I have found though is that the majority of people see a facial garment as a device to hide the face, often referring to the Face Corsets as Face ‘Masks’. As I see it a mask is intended to hide the identity of the wearer whereas the Face Corsets are intended to alter the appearance of the wearer by manipulating the skin of the wearer. The intention is do ‘display the wearer in a different way’.

Many people seem to assume that a facial garment has some kind of sexual connotation. I tell you, the amount of enquiries I’ve had from PVC clad ‘exotics’ looking for a bespoke PVC Face Corset. That’s not my scene and not why I made the work, which is why I’ve never sold or given a piece away. I don’t want to be responsible for making something that could cause physical harm to a wearer/user. There did come a point where I decided to make the Face Corsets out of fabric as far removed from the S&M scene as I could imagine. I used old suit material, my old shirts, that kind of thing but regardless, the facial locating of the Face Corsets was still read by viewers and having aesthetics which alluded to a sexual/menacing/disguising. This is why I ‘buried’ the Face Corsets.

What exactly are the Bioactive© glass facial implants you mentioned earlier?

The implants are made from a special glass that contains a combination of other components that make the glass less prone to rejection by the body. Bioactive glass was invented by Prof Larry Hench as a material to repair massive bone injuries of US servicemen injured in the Vietnam War. Even though the Bioglass© in a powdered/paste form did bond bone fragments, the material was not load bearing. Dr Thompson (Ian) has recently been casting the glass into small monolithic forms to repair non-load bearing bone injuries, particularly of the face. When I came on the scene, Ian was by his own admission using fairly primitive casting and carving methods. The skills I acquired in mold making and casting I picked up at University and at a later post in bronze casting foundry enabled me to work with Ian to try out new lost-wax casting techniques for the production of patient specific implants. Since then, the production methods of the implants have advanced and this element of the collaboration has run its natural course.

For ‘Project Façade’ you collaborated with Dr Andrew Bamji, Consultant Rheumatologist and Curator of The Gillies Archives, and Dr Ian Thompson from the Department of Oral Maxillofacial surgery at King’s College. How did you get to work with scientists?

It’s always the ideas for the work I make that lead me to meet the people I work with whether they be Dress Historians at the V&A, Scientists at University Hospitals, Family Historians based at the National Archives at Kew or Army Surplus suppliers in Portsmouth. I don’t have a specific desire to work with scientists, that’s just the direction the work has taken me.

Top V: Sketch proposing grafting skin to replace scarred cheek and Skin from tubed pedicle 1. in place on chin and nose.

How difficult has it been to trace the records of men injured and disfigured during the First World War? Can you tell us the story of one of those injured Servicemen that you found particularly touching/interesting/meaningful?

In so far as tracing the medical records, this was pretty straightforward. When I first became interested in finding out more about the origins of facial reconstruction, I recalled seeing a very short clip of an interview on a TV documentary which mentioned the pioneering surgery developed by Sir Harold Gillies during the First World War to repair horrific facial injuries. A web search brought the Gillies Archive to my attention so I booked an appointment to meet the Curator Dr Andrew Bamji (who was the chap on the TV documentary) and see some of the records. On first sight I was overwhelmed by the amount of material Andrew had collated. The Archive holds somewhere in the region of 2500 documents recording with photographs, pre-op sketches, plaster casts and handwritten notes, the surgeries the patients underwent under Gillies.

I was originally drawn to the Archive because of an interest in the surgery yet I found myself becoming incredibly curious to find out more about the post-surgery stories of the men treated by Gillies. However, only a handful of the records Andrew has collated tell the pre-injury and post-surgical stories of the men and this is largely due to Gillies patients sending him photographs and letters to let him know how they were getting along in life.

The Plastic Theatre, Queen Mary’s Hospital, 1917. Harold Gillies is seated on the right (image reproduced from the Gillies Archive)

The Plastic Theatre, Queen Mary’s Hospital, 1917. Harold Gillies is seated on the right (image reproduced from the Gillies Archive)

I was keen that the work I was embarking on making didn’t just tell the surgical stories of individual men but the personal stories also. I didn’t want the men to be defined by their injury and subsequent surgery. So once I had selected a small group of men whose stories I would like to tell, I employed Genealogist Elizabeth Evans to take the information we had and on the 10 men I had selected and search the archives at the National Records Office at Kew to see what additional information we could find. Some of the men had very little information other than census records and Regimental war diary entries by their Commanding Officers. Others however had details on the men’s trade before joining the Armed Forces, details of family members and in one case in particular, personal letters from nursing staff pleading with higher ranking officials for patients to be admitted to the plastic surgery unit at Sidcup for their facial injuries to be treated.

There are so many stories that have emerged over the past two years its hard to say which has touched me the most. Willie Vicarage the Welsh watchmaker who was so badly burned in the Battle of Jutland he lost most of the skin from his face, his nose, parts of his ears and almost all of his fingers. Alfred Russell who received skin grafts from his buttocks to his cheeks. Alfred’s wife Florence would joke that when kissing him on the cheek she was actually kissing him somewhere else! It’s the story of 2nd Lieut Henry Ralph Lumley that really got to me.

Henry, son of Robert and Florence and elder brother of Molly was a well-educated young man working for the Eastern Telegraph Company. Having not being a member of the Officer Training Corps Henry went out of his way to train as a pilot sought special permission to do so for which he was granted and attended Central Flying School, Upavon from 15th April 1916. The first tragedy to strike was on the very day Henry graduated from flying school when his plane crashed and he suffered horrific facial burns. A letter from Central Flying School to his mother stated on the same page that her son had graduated and that his aircraft ‘met with an accident’.

Lumley

Lumley

Roughly a year after his crash, Henry was transferred to Sidcup for reconstructive surgery under Gillies who proposed removing Henry’s badly scarred face entirely and replacing it with a single, huge skin graft taken from Henry’s chest. A similar less extensive procedure had proved highly successful for the aforementioned Willie Vicarage a month earlier. Henry’s surgery was more ambitious and partially due to Henry’s weakened condition the graft rejected and Henry died a few days after his surgery.

Gillies continued to encounter similar injuries to pilots and sailors and as a result of the failure of Henry’s surgery; Gillies began repairing full facial burns in stages, thus giving the patient chance to recover between surgeries. Henry’s death brought about an entire reassessment as to how to treat such injuries and hundreds of patients benefited from what was learned from Henry’s tragic surgery and paved the way for the highly successful skin grafting surgery performed on the self styled World War 2 pilots ‘The Guinea Pig Club’ over 25 years later.

As a result of the record search, I discovered Henry was buried close to my home so I took it upon myself to visit his grave. Something I never envisaged doing at the beginning of the project. Tucked away in Hampstead Cemetery is a small family headstone naming his mother, father and sister along with Henry. Sitting by Henry’s headstone for a couple of hours and being physically that close to him made me realize this was more than just ‘a project’ to me. Here were stories about incredible people that needed to be told.

William Spreckley

William Spreckley

For Project Facade you are creating a series of garments. What are you trying to achieve or communicate with these pieces? How do they complete or respond to your previous work, The Face Corsets?

The main aim of the work initially was to communicate an understanding of the pioneering surgery Gillies performed on his servicemen patients. Now though it is more about telling the stories of the people who underwent this surgery, who they were, how they came to be injured, illustrate the surgery they underwent and how they dealt with the physical and psychological consequences of receiving this surgery. I’m very much a believer that ‘you wear your history on your face’, particularly with these men. The military uniform, itself a record of the wearers military service, seemed a perfect vehicle to tell these fragmented ‘patchwork’ stories. Gillies patients ended up ‘wearing’ their military history on their faces for the rest of their lives. The uniform sculptures and accompanying face garments pool all the information I have from a variety of sources to present a collage of experience of that individual. The facial garments made from identical fabric as that of the uniforms represent the military history being worn on the face and act as an anchor point for the illustration of movement of skin by Gillies from other parts of the body to the face. I was keen that the work did not replicate injury. That in my opinion would be crass.

As far as I’m concerned, if the work I make merely provokes viewers to want to find out more about these amazing heroic people and acknowledge their sacrifice, it has been successful.

Walter F.

Walter F.

Did the fact that you have spent several years working on this project changed the view you have on your own appearance, the fact that cosmetic surgery is getting mainstream and (if you have any) beauty ideals?

Actually yes. In my youth I was something of a ‘peacock’. Because of the last couple of years work, I don’t worry about putting on a little weight, the dark circles under my eyes, my slightly less elastic skin. This is just how I am. I’m more concerned that my back doesn’t work quite as well as it used to. I must say though, the plethora of cosmetic surgery TV shows really makes my blood boil I just wish a fraction of airtime was given over to tell the stories of the servicemen Gillies treated to restore function to their faces as is given over to people having the fat sucked out of their backsides.

Speaking personally, my beauty ideals tend to be personality based but if we are going to get superficial, I do like ladies with gaps between their front teeth that speak with a lisp and a top lip that looks like its been smeared flat! I find difference attractive.

What can members of the scientific community learn from your own artistic research?

Speaking very generally, to be open to collaborate across disciplines, but that goes for anyone in any profession, but not to ‘force’ the collaboration. Let it take you where it will. Fellow artists have asked me on a number of occasions as to how they can have their work taken on board as part of clinical practice in health care and my answer never changes. ‘I don’t know!’ That has never been an aim of the work I set out to do. If it contributes towards clinical practice by proxy, that’s great because its evolved naturally rather than by design. As far as I’m concerned the main audience I want to connect with is the general public. Essentially that’s who the work is about.

Any upcoming project’s that you could share with us?

Project Façade Phase 2. I’m trying to trace as many descendants of Gillies patients to record their memories of their ‘Gillies repaired’ relatives to find out and preserve their later life experience. This has becoming a life long undertaking for me.

Thanks Paddy!

All work produced by Paddy Hartley and associated Gillies Archive documents and objects can be seen at the first Project Façade exhibition ‘Faces of Battle’ produced with and opening on November 10, 2007 at The National Army Museum, London.

For further details contact Paddy directly on paddyhartley at projectfaçade dot com or visit the project website to find out more about the stories of the men and Paddy’s responses.