Loving The Machine: The Art and Science of Japanese Robots, by Timothy N.Hornyak (Amazon USA

Loving The Machine: The Art and Science of Japanese Robots, by Timothy N.Hornyak (Amazon USA

Publisher’s blurb: While U.S. companies have produced robot vacuum cleaners and war machines, Japan has created warm and fuzzy life-like robot therapy pets. While the U.S. makes movies like Robocop and The Terminator, Japan is responsible for the friendly Mighty Atom, Aibo and Asimo. While the U.S. sponsors robot-on-robot destruction contests, Japan’s feature tasks that mimic nonviolent human activities. (…) What can account for Japan’s unique relationship with robots as potential colleagues in life, rather than as potential adversaries?

I’ve been looking for a book that answers that question for quite some time now.

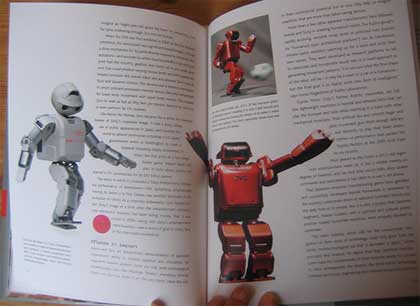

Let’s divide the book in two parts and start anti-chronologically. The second part is dedicated to the country’s current state of robotic technologies, and what the future holds. If you only expect to discover new robots, you will be disappointed: we’ve all read about the like of Murata Boy the cyclist, Actroid the booth babe and Tomotaka Takahashi‘s super cute Neon in blogs such as the one where Hornyak documents his latest findings about robots. But that shouldn’t stop you. What you won’t find in blogs are information and quotes taken from conversations that the author had with today’s robot engineers and experts.

What fascinated me most in the book was the first half of it, the one that looks at Japan’s historical connections with robots, in particular its “karakuri” tradition and the influence that manga characters have had on the public’s imagination.

Just like our Western automata, Karakuri were made to entertain and create a sense of wonder. The author argues that unlike their more sophisticated Western counterpart the Japanese automata were regarded more as dolls than machines. The aim was not to achieve realism but to charm the audience, it was art for its own sake rather than the advancement of science. It all started during the Edo period, when Japan was completely isolated from the rest of the world. Around 1662, a businessman named Takeda Omi opened an amusement park which quickly became famous for the theatre performances that starred automats as well as puppets and human actors. The mechanisms of the dolls were carefully hidden behind their kimonos and delicate smiles. Much of their technology owe much to the Western guns and clock-making know-how introduced in the country before the sakoku, the national seclusion period that would last some 250 years.

Recreating dolls would be impossible were it not for the Karakuri Zui, a treatise on “Illustrated Machinery” written in 1796 by Yorinao Hosokawa. The engineer, artisan and inventor described in three volumes how to make four kinds of wadokei clocks and nine types of mechanical dolls, including a famous boy which courteously serves tea to guests while nodding the head.

The Yumihiki Doji aims his bow

The Yumihiki Doji aims his bow

Another Estern influence on Japanese robotics was Karel Capek’s R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots), the play that gave its name to robots. However, it might well be Mighty Atom/Astro Boy who left the biggest imprint in Japanese minds when it comes to robotics. Osamu Tezuka‘s character embodies the belief that robots can not only be friends with human beings but might also be the country’s salvation. An idea that shouldn’t be underestimated, especially if you think that the manga hero was born in the mind of a young medical student who was deeply affected by fire-bombed Osaka during WWII. According to Nagoya University robotics professor Tohio Fukada, the desire to create a robot like Atom exists among Japanese roboticists in varying degrees.

Astroboy by Hiroshi Araki, 1993

Astroboy by Hiroshi Araki, 1993

Astro Boy gained recognition in Occident as well. In particular in 2004 when he was inducted into Carnegie Mellon University’s Robot Hall of Fame. The jury decided that Astro Boy deserved the title for being “the first robot with a soul.”

The book keeps on with a look into the legacy of other popular characters such as Ironman No. 28/Gigantor (which might soon get its own statue in Kobe), , Mobile Suit Gundam, Neon Genesis Evangelion, etc. And also the Mecha, walking robotic vehicles controlled by a pilot. My favourite was Grendizer or in french as Goldorak with his fulguro-poings and missiles gama. Il traverse tout l’univers aussi vite que la lumière. Qui est-il? D’où vient-il? Formidable robot des temps nouveaux. I never missed an episode of the series, had all the gadgets (or stole them from my little brother), and had a ridiculous crush on Actarus its pilot.

There’s one really annoying thing about that book that pops up once in a while: the style. Most of the time it’s ok, usual essay style, nothing to complain about and who am i to give lessons of writing style anyway? But here and there appear some paragraphs that seem to be taken from a cloying novel, i don’t know what motivates these grandiloquent endeavours but they really weaken the otherwise compelling “plot”.

Related: Where Anime and Art Meet: Gundam Exhibition, From Anime Center to Manga Museum, Robots. Better than people?

![7 art and tech ideas I discovered at Meta.Morf 2024 – [up]Loaded Bodies 7 art and tech ideas I discovered at Meta.Morf 2024 – [up]Loaded Bodies](https://we-make-money-not-art.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/53705969154_73dfdfea6f_c-300x200.jpeg)